| On days like these, it's easy for those of us trying to analyze markets and the economy to slip into the realms of something more like intense literary criticism, or even psychoanalysis. The Federal Reserve announced that it was raising its target rate by 25 basis points, hiking for the eighth meeting in succession. Markets briefly wobbled on the news; and then Chair Jerome Powell embarked on his press conference, traders released their inner Sigmund Freuds and Jacques Derridas, and risk assets headed for the moon. Here's a first stab at deconstructing what went on. The Fed's initial statement said in as many words that further rises in interest rates would be appropriate. This instant reaction to the communique from Seema Shah, chief global strategist at Principal Asset Management, was totally reasonable: The Fed has delivered a reality check to markets, reiterating that while inflation has decelerated, there is still a long road ahead... that will take policy rates to at least 5% and likely higher. Certainly, this is an important message to get right. The recent loosening in financial conditions threatens to undo much of their good work and raises the spectre of a renewed surge in inflation later this year if the Fed cannot regain control of market expectations.

What now remained, as trailed by Points of Return yesterday, was for Powell to follow through with aggressively hawkish rhetoric, and particularly to inveigh against the easing of financial conditions that has been caused by the market rally. Then his press conference began, and the more he spoke, the more the market rallied. The Nasdaq Composite ended the day up 2% exactly, while bond yields fell: By the time the dust settled, the market was even more convinced of significant easing before this year is out. This is how the projected course of the fed funds rate over the next 12 months changed from Tuesday to Wednesday, according to Bloomberg's analysis of fed funds futures: So, no, Powell didn't succeed in sounding very hawkish. Investors didn't take his professions of tightening intent at all seriously. This explanation from BMO Wealth Management's Chief Investment Strategist Yung-Yu Ma gives an idea of where Powell went wrong: While the FOMC statement struck a balanced tone, the Q&A session of Chairman Powell's press conference seemed bent on peeling away the hawkish layers and pulling out the inner dovishness. A barrage of questions pressed Chairman Powell on whether future interest rate increases were needed in the face of falling inflation. Toward the end, Chairman Powell showed the last of his cards and indicated that he believes in a path to getting inflation down to 2% without a significant economic decline or significant increase in unemployment. We are in the early stages of disinflation, he asserted, and it will take some time to spread through the economy... The ingredients for a soft landing are falling into place. The Fed is struggling to maintain a semblance of hawkishness, but at this point is probably just along for the ride.

Arguably, his critical mistake came early in the Q&A, when he was asked if he was worried that financial conditions had eased. This appeared to be a straightforward opportunity for him to say "yes" and browbeat the market. He didn't. Instead, remarkably, he said that financial conditions had tightened. They haven't. These are the measures published by Bloomberg (in which a rising line shows loosening conditions) and by Goldman Sachs (in which a falling line means conditions are getting easier). They agree that conditions are easing: It was at this point that traders started piling into both stocks and bonds. Neil Dutta, head of economics at Renaissance Macro Research, said that Powell's mischaracterization of financial conditions "was dovish in its own right" and that the odds were increasing the Fed's "flirtation with the soft landing today increases the risk of a harder landing later." Another critical mistake (assuming he wanted to appear hawkish) came in response to a question about the "dot-plot," which in its last edition showed Fed governors expecting the fed funds rate to stay above 5% by the end of the year. Were those dots still valid? This was the response: We have inflation moving down, you know, into somewhere in the mid-3s or maybe lower than that this year. We will update that in March. That is what we thought in December. Markets are past that. They see inflation coming down in some cases much quicker than that, so we will have to see. We have a different view, a different forecast really. Given that, I don't see the rates coming down; as I mentioned, if we do see inflation coming down much more quickly, that will play into our policy-setting, of course.

Powell reiterated that he thought it was easier to correct course after an over-tightening than to deal with the consequences of easing too soon. But in responses like this, he appeared to confirm to the market that if inflation does come down reasonably quickly, rates will follow. This applies even though Powell said in as many words that he didn't see rates being lowered. Deep textual analysis of Fed communications has been around for a long time, and these days people tend to look more at spoken than written communications. But things may be going too far here. To some, Powell's failure to complain about easing financial conditions was a Freudian "tell" that the Fed thinks it's done its job; others argued that he misspoke and tried psychological analysis of market investors instead, contending that they had heard only what they wanted to hear. The debate by the end of the day was between whether Powell had set out to sound hawkish and done a really bad job of it, or whether he had inadvertently given the game away that the Fed thinks they'll be cutting soon. This is a field of analysis that most people in charge of managing money don't know much about. They do, however, know much more about economics. And that's where the attention should be directed… —Reporting by Isabelle Lee A final serious problem for the Powell messaging strategy is that describing the Fed as "data-dependent" directly implies that we needn't take too much notice of its forward guidance. Bill Adams, chief economist for Comerica Bank, puts this nicely: Powell acknowledged the possibility that the Fed could ultimately raise rates above the peak rate in the [dot-plot], and also that the rate could peak below it. He also used the phrase "data-dependent" to describe how the Fed would make decisions near-term. Am I stating the obvious by writing that an explicitly data-dependent Fed can't expect financial markets to attach too much weight to its forward guidance?

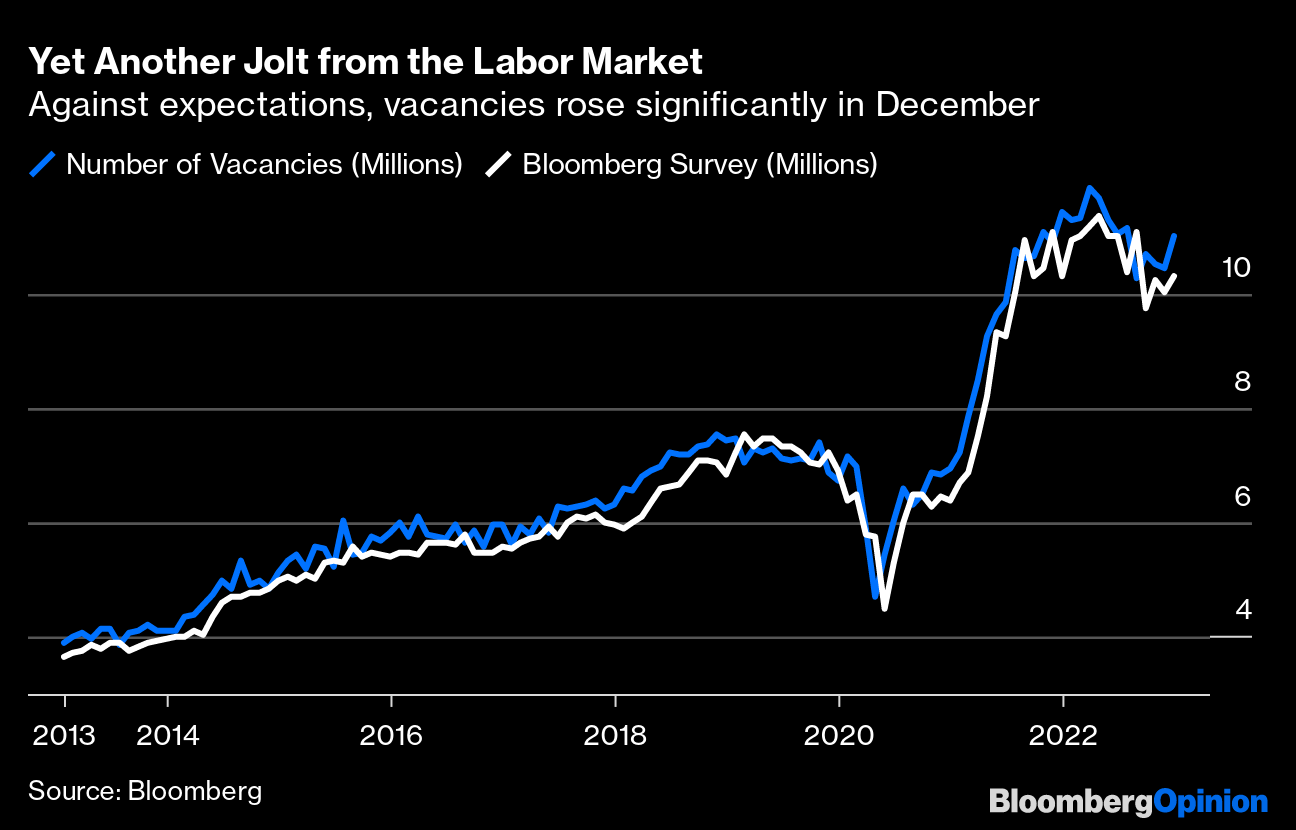

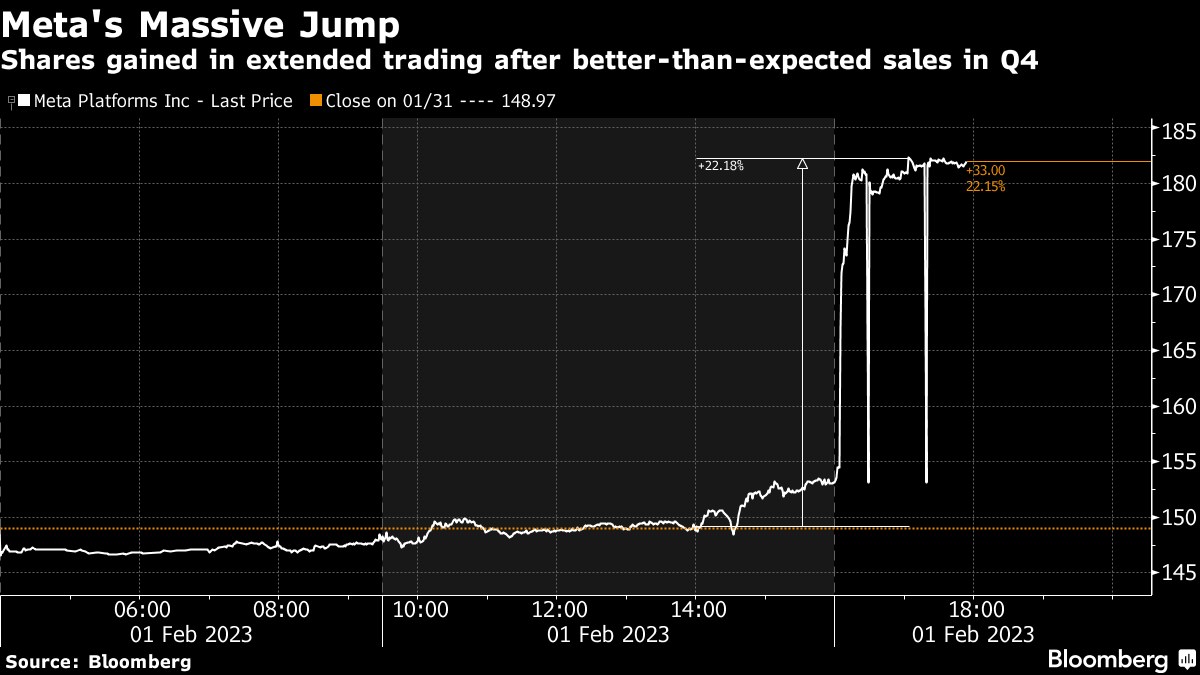

This is very true, but it also points to an issue with the strong market reaction. Where data-dependency takes you depends on which data you choose to depend on. Three reasonably important data points from Wednesday morning would lead you to three different paths for the Fed. To start with, the JOLTS survey showed job vacancies rising again, very much counter to expectations. There are now roughly two vacancies in the US for every officially unemployed person. That implies overheating, no reason for the Fed to fear that it will provoke a recession, and every reason to keep hiking:  But then we come to the survey of private sector employment by the ADP payroll processing group, which every month attempts to preempt the official non-farm payroll numbers. This suggests that the labor market is at last calming down, with the smallest increase to payrolls in almost two years, while doing nothing to raise any great fears. This would imply the Fed is nicely on target for a soft landing, and can probably start to let rates come down by about the end of the year: But then we come to the ISM supply managers' survey of manufacturing, which has proved to be a great leading indicator for the economy over the years. Most eye-catching was a continuing drop in new orders, implying demand is dropping sharply. As this chart shows, they have never fallen this low without soon ushering in a recession. On the face of it, this implies an imminent hard landing and a pressing need for the Fed to pivot, and pivot soon: Even data-dependency doesn't help much at present, then. With an economy so difficult to read, it might be better to devote efforts to working out exactly what scenario is unfolding. The Fed seems more uncertain than a very significant bloc of traders who have been moving prices in the last couple of months. In that uncertainty, I think the Fed is right. Just a reminder that the Fed is no longer the only game in town. Within hours of this newsletter, the Bank of England and the European Central Bank will meet. The BOE, with more serious recessionary risks on its hands and higher inflation, has a horrible job; meanwhile, the ECB is shaping up as the last hawk standing. In December, an ECB meeting also came a matter of hours after the Fed had spoken — and proved to be far more impactful. To demonstrate this, look only at the differential in 10-year yields between the US and Germany: If the ECB continues its hawkish routine, we can expect another jolt higher for the euro (which reached $1.10 for the first time since April in the aftermath of the press conference) and further weakness for the dollar — which will in itself ease financial conditions in the US and raise inflationary pressure. Prepare for yet more meta-analysis when Christine Lagarde takes questions. And speaking of meta-analysis... Almost exactly a year ago, Meta Platforms Inc. suffered a Kafka-esque fate and went through the stock market equivalent of waking up and finding that it had transformed into a large insect. In one day, investors responded to its earnings for the fourth quarter of 2021 by slashing $250 billion from its market cap. Times have changed. Kicking off a two-day big-tech earnings season with Apple Inc., Amazon.com Inc. and Google parent Alphabet Inc. was Meta, and for a change it did not disappoint. Mark Zuckerberg's firm soared as much as 22% in extended trading after the social media giant reported better-than-expected sales during the holiday quarter, fueled by strong demand for advertising. The fourth-quarter results run against anecdotal rumors that Facebook and Instagram are not as cool as they used to be. Turns out, people are mistaken.  If the gains stick, Meta will be hovering around the same level it first reached five years ago in November 2017 — and which it last achieved in July 2022. The advance seen Wednesday evening also marks an astonishing 109% rally since it hit a low only two months ago. Sounds good? Well, if Meta holds the rally, it will still put the stock 52% lower from its September 2021 high. But it does show signs of recovering from the brutal metamorphosis that the market imposed. Confused? What this reinforces, arguably, is that no one truly knows how to value sprawling tech behemoths like Meta. Put simply, when the stock debuted in 2012, the company was valued at $104 billion — which put it just outside the top 20 biggest companies in the US, with a market cap just above Amazon's. Since then, it has been through many evolutions (including even a change of name), and it's now valued at $401 billion, making it among the top 20 most valuable companies worldwide. The after-market rally stands to make it bigger than JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Johnson & Johnson once again. In terms of equity pricing, where Meta sits today is a whopping 950% higher than its 2012 price. This is what portfolio managers mean when they say time in the market is more important than timing the market. Why did Wall Street cheer Meta's results Wednesday quite so loudly? It can best be attributed to a beat on sales, a rosy outlook for the rest of this year — and a huge $40 billion share buyback. Investors tend to prefer it when cash is paid to them, rather than invested in, say, the metaverse. Revenue for the company's fourth quarter was $32.2 billion, slightly better than Wall Street estimates of $31.6 billion. Pair that with Meta projecting revenue of $26 billion to $28.5 billion for the first quarter, roughly in line with estimates of $27.25 billion while its 2023 expenses will be less than previously forecast, lower by about $5 billion, and you have justification for some excitement. On top of that, Chief Executive Officer Mark Zuckerberg claimed the company is making progress with its investments in artificial intelligence. And going back to people not thinking Meta isn't as cool anymore, maybe they have to reevaluate. The number of daily active people (DAP) using one of Meta's sites — Facebook, Messenger and Instagram — amounted to 2.96 billion, up 5% compared to last year.  Cool again? Photographer: Tiffany Hagler-Geard/Bloomberg All of this was quite a transformation after Meta suffered the first two quarters of year-over-year revenue declines in the second and third quarters of 2023. Life might now get easier for tech companies, Meta included, as the Fed slows its rate-hike pace. Tech companies, after all, are prone to fears of rising interest rates, especially since many are valued based on their projected profits far into the future. Here's Sophie Lund-Yates, lead equity analyst at Hargreaves Lansdown: Borrowing costs have still been pushed to their highest levels since 2007. That is a very challenging environment in which to be selling ad space, virtual or otherwise. There are also Meta-specific issues at play, which includes competition. TikTok, and increasingly Pinterest, are muscling in to take the shine away from Facebook and Instagram's attractiveness to marketers.

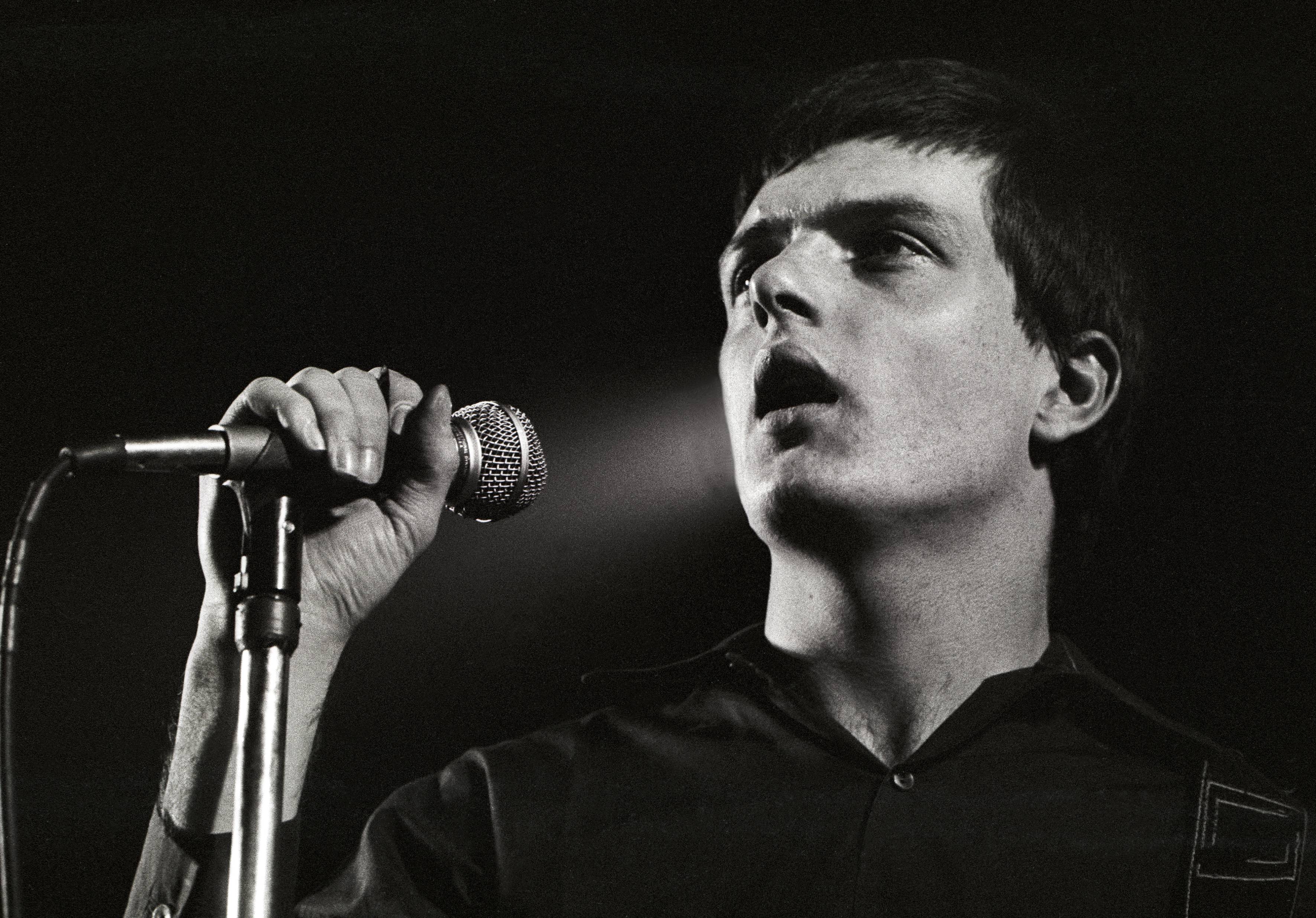

While the overall report was positively received, it doesn't clear the outlook for Meta. Interest rates are still high, recession risks are still there and consumer sentiment has shifted. (The company does at least appear to have been ahead of the game last year when it fired 13% of its workforce in its first major layoff.) This is perhaps why Zuckerberg said Meta is entering a "phase change" focused on efficiency, emphasizing that the years of rapid growth are perhaps over. Maybe that isn't a bad thing. It would certainly beat the kind of sudden and brutal metamorphic change that the market forced on Meta a year ago. — Isabelle Lee Talk of new orders draws my attention to the news that New Order has been nominated for the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, along with its predecessor Joy Division. Other acts up for induction include Kate Bush and Iron Maiden. There's an argument about whether New Order, which came into existence after the suicide of Joy Division's lead singer Ian Curtis in 1980, should be treated as a wholly separate act. I don't think so. Earlier New Order songs like Age of Consent and Ceremony seem to me to have a direct lineage from Joy Division songs like Transmission or Novelty. Later in their career, songs like True Faith or World in Motion (the coolest football song ever) did show rather a bigger transition from the deep gloom of Joy Division songs like She's Lost Control. But if you listen to Love Will Tear Us Apart, a very sad song but also a truly beautiful one, you can hear that with Ian Curtis they were getting much more interested in melody and keyboards. Blue Monday was on the way.  Ian Curtis and Joy Division performing at the Lantaren in Rotterdam. Photographer: Rob Verhorst/Redferns/Getty This 1984 conversation between the remarkable combination of Tony Blackburn (a veteran DJ), George Michael of Wham! and Morrissey of The Smiths reveals that Joy Division's reputation took a while to take hold. All of them felt that Curtis's tragic death dominated the way his band was viewed. Counter to expectation Morrissey, it turns out, didn't like Joy Division (he saw them "a few times, by accident") while Michael liked them a lot. (Tony Blackburn didn't like them at all, which isn't surprising.) Their reputation has climbed ever since, in part thanks to brilliant movies such as Control (its treatment of how Curtis reached his end, which many will find distressing, is here), and in part because their music has turned out to pass the test of time. Personally, I hope Joy Division/New Order are inducted, preferably as one entity. They should be in already. And the same goes for Kate Bush. (Also, I have a soft spot for Iron Maiden, and not only because their song Number of the Beast has been very handy for me whenever invoking the S&P 500's post-crisis low of 666. I hope they get in.)

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close.

More From Bloomberg Opinion: - Robert Burgess: Fed Pivot Is Dead. Long Live the Fed Pirouette.

- Tyler Cowen: Is the US Economy in Danger of Reheating?

- Julian Lee: Russia's War Will Destroy Its Energy Market, Maybe Forever

Want more from Bloomberg Opinion? {OPIN <GO>}. Web readers click here. |

No comments:

Post a Comment