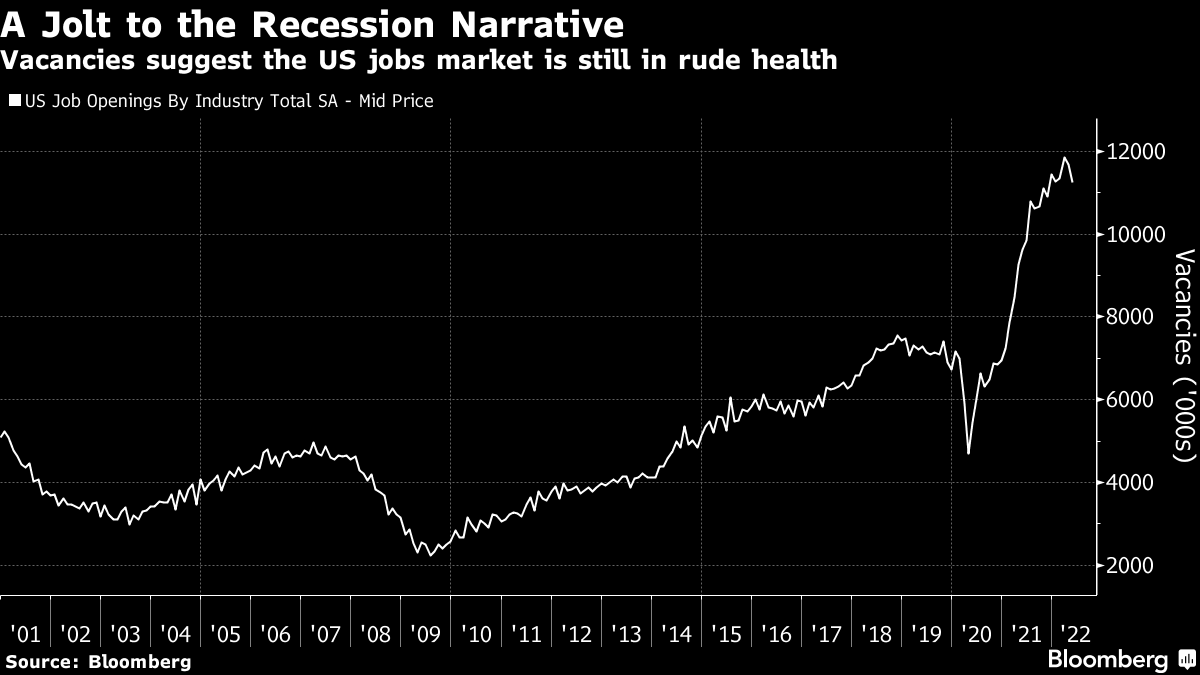

| It's my job to make sense of markets, and I do it gladly. It can be fascinating. The problem is that this implies that there is some sense in what markets are doing. At times like this, such a belief grows much harder to sustain. Let's start with the behavior of the two-year Treasury yield, one of the most important building blocks of global finance, over the last month since the eve of publication of shockingly bad inflation data for May. It's been quite a ride. In the space of a month, two-year rates went from 2.7% to 3.4% and back again — and in the last 24 hours, they've made it back to 3%. Somersaults like this are just not normal. Why did the bond market make its latest swerve? In the current febrile environment, data that are generally regarded as distinctly second-tier can have a big impact. Wednesday morning brought at least two data points to spark the thought that maybe a recession isn't yet inevitable, even if the market has suddenly tried to price that in. First, the JOLTS survey of vacancies showed more job openings than had been expected. Yes, the total number is down slightly, but it's still far higher than had ever been seen before the post-pandemic reopening. On the face of it, with that many employers looking to hire that many people, it's crazy to brace for an imminent recession:  Then there was the purchasing manager survey of services, to follow last week's very disappointing data on manufacturing. The services sector is at a different point in reopening, and remains in a much healthier state than manufacturing; the overall figure is down, but remains strong and better than expectations. Perhaps of particular interest given the inflation angst, the survey also showed that service providers are finding that prices are still a serious problem. The number has dipped slightly, but is still higher than it had ever been before last year, save only for September 2005, the month of Hurricane Katrina:  At the margin, both of these data points suggest we should be a bit more cautious about assuming that the Federal Reserve will have to desist swiftly in its interest rate hikes. For those wanting evidence that the economy is already slowing down, there were mortgage application data. One of the most immediate impacts of a tightening monetary policy and higher rates should be a decline in the demand for mortgages, and that seems to be exactly what the Fed has wrought:  Taken together, this data wouldn't normally fuel quite such a shift in the bond market. But times aren't normal. Also, more importantly, Wednesday afternoon saw publication of the minutes to the Federal Open Market Committee's June meeting, which you can find here. There were no big surprises for anyone who had listened to Jerome Powell's press conference on the day of that meeting, or to his words last week at the central banking powwow in Sintra, Portugal. But with sentiment taking hold that the Fed would soon have to reverse course, there had been hopes that the fine print would reveal "get-out" clauses to provide an excuse not to hike rates too much. They weren't there. That was disappointing. You can find Bloomberg's analysis of the minutes here. The main passages to read, I'd argue, are as follows: Participants concurred that the economic outlook warranted moving to a restrictive stance of policy, and they recognized the possibility that an even more restrictive stance could be appropriate if elevated inflation pressures were to persist.

This rams home the message that the Fed is prepared to make interest rates outright restrictive, and not just neutral. Then comes: Participants noted that, with the federal funds rate expected to be near or above estimates of its longer-run level later this year, the Committee would then be well-positioned to determine the appropriate pace of further policy firming and the extent to which economic developments warranted policy adjustments. They also remarked that the pace of rate increases and the extent of future policy tightening would depend on the incoming data and the evolving outlook for the economy.

This is the closest approach to a "get-out" clause. Once they've hiked swiftly and aggressively to reach a point where rates are restrictive, which could come as soon as September, then the Fed's governors can pause to look at incoming data before deciding what to do next. They're not, however, giving any particular sign that they expect to have to start cutting rates quickly. Finally: Many participants noted that the Committee's credibility with regard to bringing inflation back to the 2% objective, together with previous communications, had been helpful in shifting market expectations of future policy and had already contributed to a notable tightening of financial conditions that would likely help reduce inflation pressures by restraining aggregate demand.

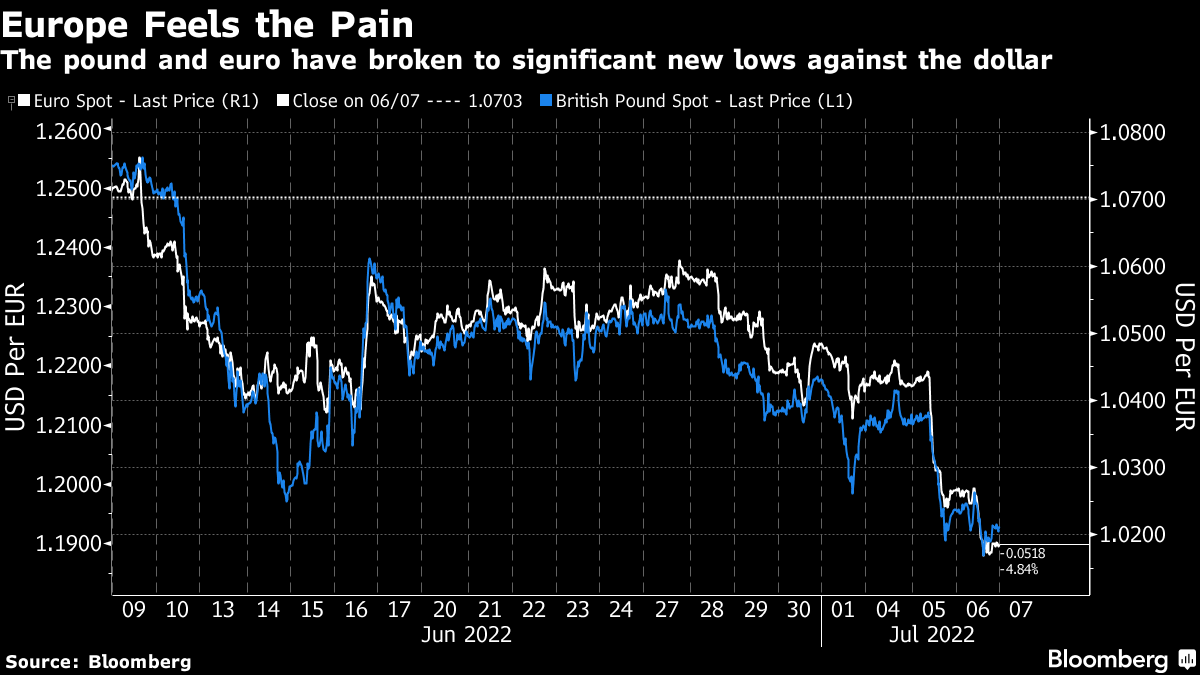

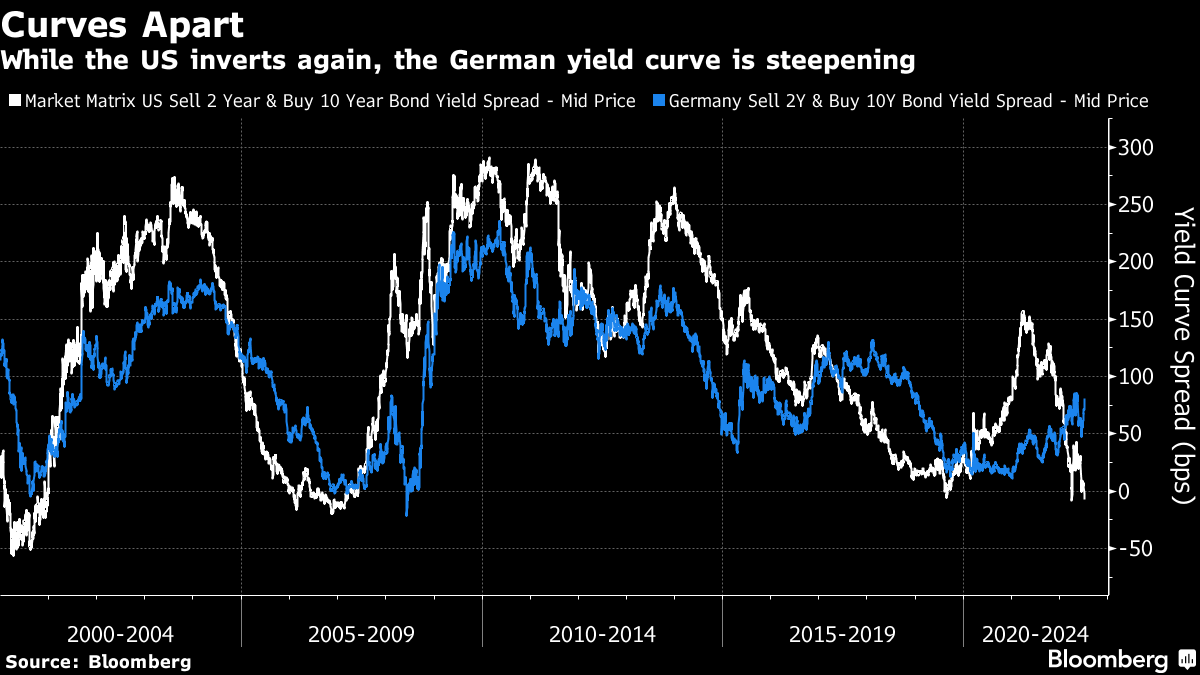

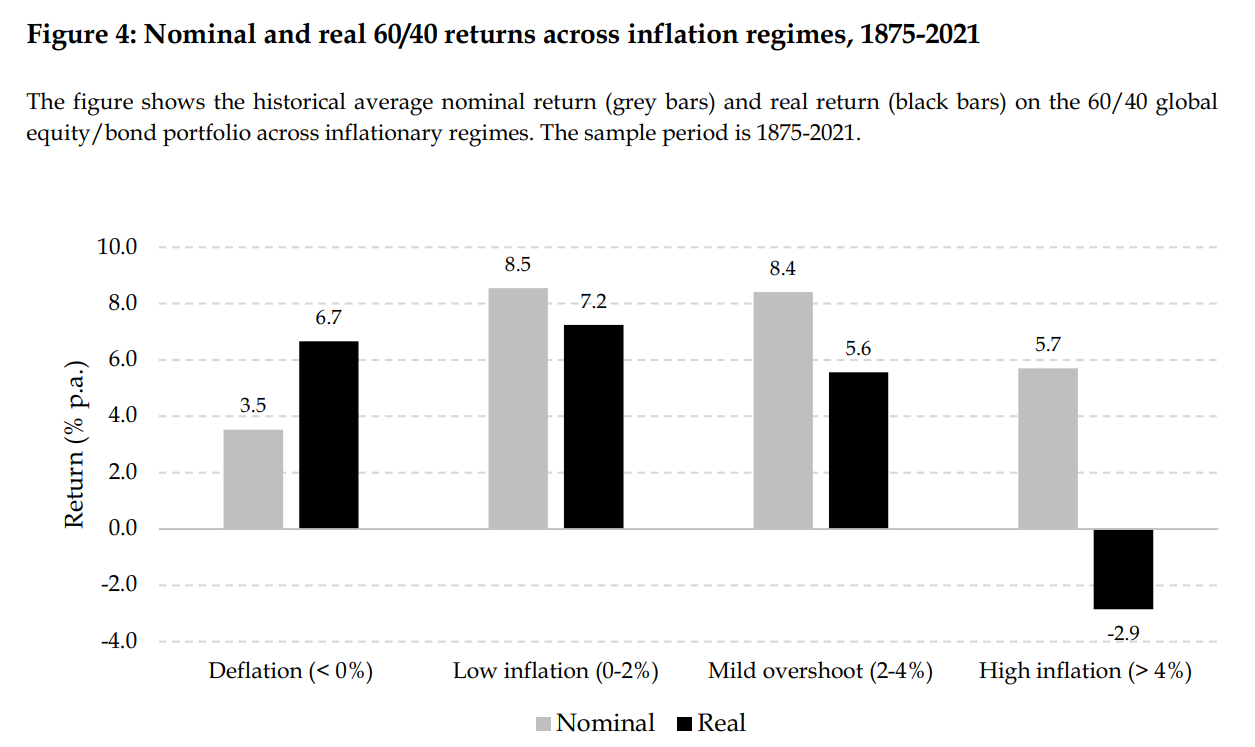

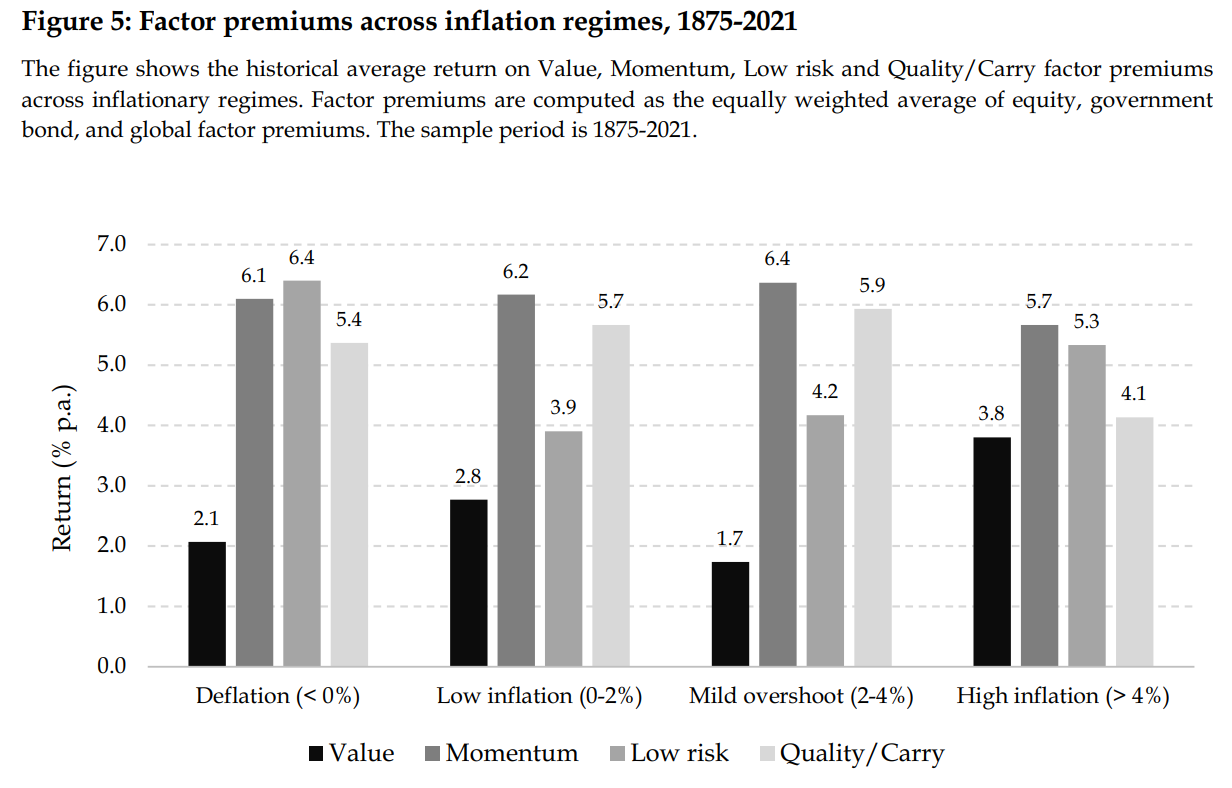

There are no apologies here for scaring the markets and pushing up rates. As most readings of the vexed history of monetary policy in the 1970s would tell you, the Fed's priority now is to regain lost credibility and bring inflation expectations under control. Retreat without doing this and they evidently think that there could be further damage to the economy. None of this should have come as a nasty shock for anyone paying attention. But the lack of the hoped-for pleasant surprise, in this environment, sent bond yields back upwards. While the excitement intensifies in the US, European bond markets are also moving to set new extremes. However, they aren't going in the same direction. That ratchets up the dollar ever further. The British pound dropped below $1.19 for the first time since 1985, while the euro fell under $1.02 for the first time in two decades. The last few days have brought no particular new news on the British or eurozone economies, but that's certainly not what you'd think to look at the currency charts:  Why is this? The prime driver, I think, is a dramatic divergence in the way the bond market views the economy on either side of the Atlantic. Usually, the bund and dollar yield curves move in the same direction. In other words, at any one time the gap between 10- and two-year bond yields will be widening or narrowing in unison. But now the German bund yield curve is as steep as it has been since 2019, while the Treasury yield curve is emphatically inverted after the last few days' trading. On the face of it, that means that bond traders think the US faces a recession, while still seeing the likelihood of more inflation in Germany without aggressive rate hikes to rein it in:  There is at least one simple reason for this divergence: Europe is much closer to Russia, and much more dependent on its energy. Declining commodity prices globally betoken the risk of an economic slowdown, but the risk of extreme inflation in energy prices for Europe remains intense. That would act as a tax on the economy, increasing inflation and making it far harder for the European Central Bank to hike rates. This dynamic leads to a weak currency for Europe, which at least renders its exporters more competitive but also accentuates problems in paying for raw materials. But it's fascinating to see how different the pattern looks over two years and over 10. The gap between two-year Treasurys and bunds has widened above 2.5 percentage points, to a spread not seen since 2019. Meanwhile, the decline in 10-year Treasury yields means that they now trade at a slightly lower yield than bunds. The differential has been eliminated. So as it stands, the market has priced in a Federal Reserve that hikes far more aggressively than the ECB over the next two years — while also pricing the two economies to endure similarly anemic growth over the next 10. The gap is roughly as wide as in 2018, when the ECB was still intervening to keep rates negative while the Fed was trying to press on with quantitative tightening to normalize its policy. The war in Ukraine gives a good exogenous reason why the two economies are perceived to be in such different places. It's still hard to see how this dysfunction can last much longer. The Fed still wants us to brace for inflation; many in the bond market are busy betting for a decline. So, what to do? The quantitative team of Guido Baltussen, Laurens Swinkels and Pim van Vliet at Robeco Assset Management in the Netherlands has produced a new historical study looking at the performance of different investment factors and asset classes in different inflation regimes, going back to 1875. The bottom line for a classic portfolio of 60% stocks and 40% bonds is not surprising. If inflation stays reasonably under control, below 4%, then both nominal and real returns should be healthy. Low inflation between 0 and 2%, of the kind to which we became accustomed for a decade after the Global Financial Crisis, tends to foster the best real returns. The only inflation regime that brings negative real returns is, unsurprisingly, high inflation, which the researchers defined as 4% or more.  What about factor investing? A number of different market anomalies have been shown to be persistent over time. The quants tested for value (cheap will beat expensive), momentum (winners keep winning and lowers keep losing), low risk (lower risk investments tend to outperform) and quality/carry (investments generating a higher cash yield tend to do better). When defined as the return generated by going long the best securities according to a factor and short the worst, all of these factors tended at least to be positive over history over all four inflation regimes they examined. They also appeared to be relatively unaffected by the inflation environment:  If this looks suspiciously like a free lunch (and it does), bear in mind that anomalies tend to reduce or disappear once they've been discovered. Some of the big opportunities to exploit market anomalies in the later decades of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th are now much reduced or non-existent, as people have spotted and arbitraged them away. The most topical results come from their stress test, when the quants looked at results during specific bad times: (1) recession or

expansion (as defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research); (2) falling or rising earnings growth; (3) bear or bull equity markets; (4) increasing or decreasing interest rates; and (5) increasing or decreasing inflation. The sample includes 30 officially declared recessions. When looking at particular tough environments, they tested both a standard 60/40 portfolio, plus a 60/40 portfolio that had been juiced up by using factor exposures as well. Deflationary slumps turn out to be difficult but not impossible for asset allocators, as might have been guessed from the experience of life between the GFC and the pandemic. Adding the factor exposures improved returns in every case. Even without them, a 60/40 portfolio made money during recessions, falling earnings, and during the early stages of rising inflation from a low base: So if the latest market swivel is accurate, and the next few years are more like a deflationary slump, then that's not such a bad outcome for those trying to manage assets. Stagflation is a different matter. As they say: Periods of stagflation are truly bad times, as for example nominal equity returns average -7.1% per annum, yielding double-digit negative returns in real terms. During the bad times, equity, bond, and global factor premiums remain consistently positive. As such, factors help to offset some, but not all, of the negative impact of high inflation in recessionary times.

When inflation is high, any given additional problem makes it much harder to cope. If stagflation does lie ahead, then history suggests that declines for 60/40 investors are inevitable. Factor investing might reduce the damage a bit, but it can't be expected to help turn a profit: All of this research helps to explain today's bizarre atmosphere, where the prospect of a contracting economy is greeted as good news. If you are managing money, it beats the heck out of stagflation. It also suggests that there are certain investment anomalies that are so deeply rooted in human nature that they won't go away. Which is, I suppose, reassuring. The whole paper is worth reading in detail. How to come to terms with another extraordinary day in British politics, in which Boris Johnson has lost more than 40 of his ministers, faced advice from his remaining loyal lieutenants that the game is up, and still opted to press on? One serious concern is that he appears to have a plan to announce a plan combining tax cuts with spending on things that people like. That might be popular in the short run. With the currency already under siege, the chances that it could soon deteriorate into disaster look pretty high to me. As for music to accompany the day, this acoustic version of The Verve's great "Bittersweet Symphony" accompanied BBC Newsnight's list of the politicians to resign. It's very effective. The original continues to be an anthem of 1990s Britpop, with a great video. Back in the day, Margaret Thatcher inspired some great music in those who disliked her. Try Stand Down Margaret by The Beat, recorded in 1982 eight years before Margaret stood down, the Specials' cover of Bob Dylan's Maggie's Farm (which had a very different political meaning in 1980s Britain, and which they changed to "Ronald's Farm" when in the US) or Tramp The Dirt Down by Elvis Costello. Thatcher was nobody's idea of a quitter and promised to "fight on," but when she had the same experience that Johnson has just suffered, being warned by her cabinet that she didn't have their support if she tried to fight on, she resigned the next morning. Would that Johnson had her self-awareness. As it is, Monty Python as ever provides the best analogy for British politics; Johnson resembles nobody so much as the Black Knight. I still don't see how Johnson can survive very long. But it's amazing to behold what's possible if one can only lose the ability to feel shame or embarrassment.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Other Writers at Bloomberg Opinion: Want more from Bloomberg Opinion? Terminal readers head to {OPIN <GO>}. |

No comments:

Post a Comment