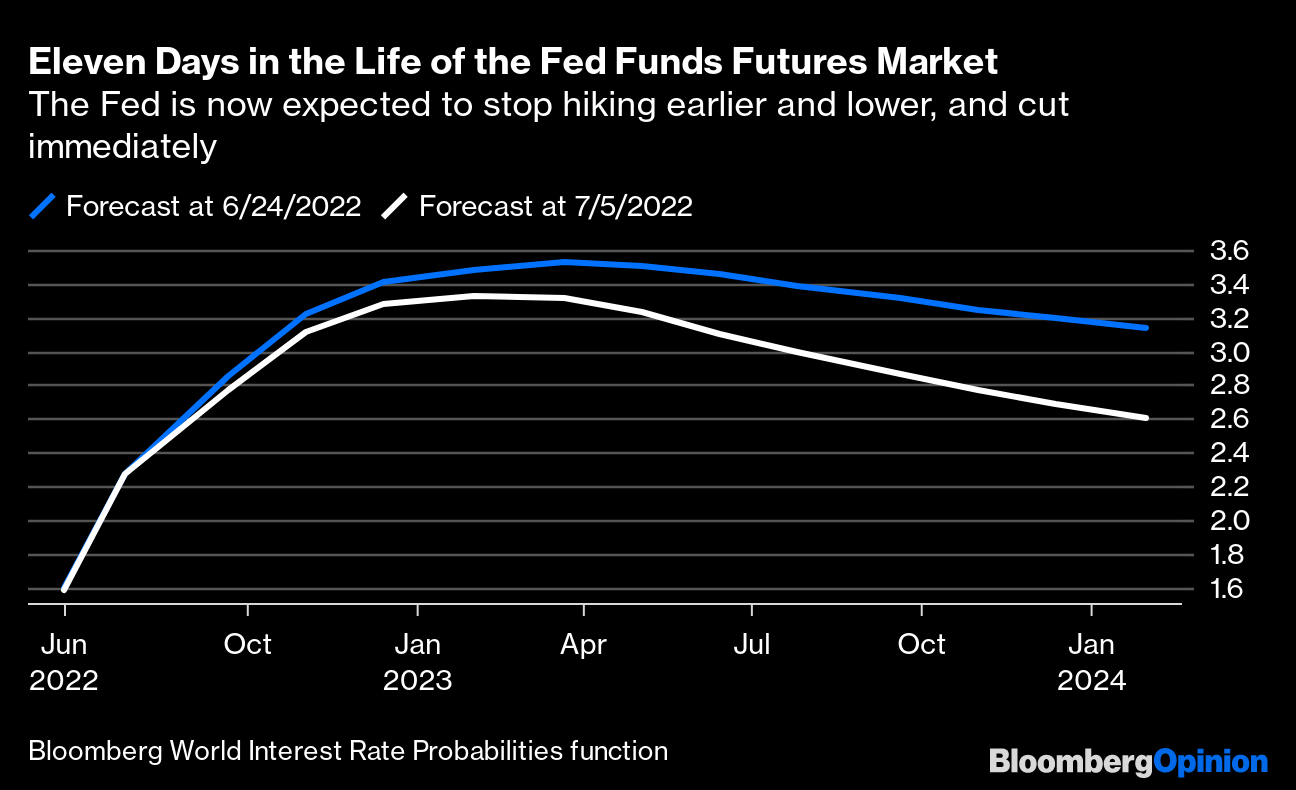

| To capture what's happening in global markets, think of a ferret in a newsroom. Back in the heyday of Fleet Street, Kelvin MacKenzie, one of Rupert Murdoch's favorite tabloid editors, would yell, "Ferret up trousers!" when a big story broke and everyone had to drop what they were doing to work on it. If that story then turned out not to be true, even closer to deadline and requiring desperate work, he'd shout, "Reverse ferret!" Markets are executing a classic reverse ferret. The key, as I've often said recently, is a change in the belief on whether the economy can withstand the higher rates that the Federal Reserve says that it's going to impose in a bid to quell inflation. Three weeks ago, there was confidence the Fed would have to hike until the pips squeaked. Now, there's a belief that it can't hike too far without forcing a recession, and thereby will be forced to cut rates again. To illustrate this, look at the implicit predictions for the fed funds rates after each of the Fed's monetary policy meetings from now until January 2024. When the contract was introduced, on June 24, the expectation was that rates would be at either 3.0 or 3.25% as 2024 started. That is now down to about 2.6%. In less than two weeks, the market has dropped its prediction for a peak rate brought forward the moment of the first cut, and forecasts a far more aggressive cutting program that will start next spring. The ferret has made a screeching U-turn:  Something similar is afoot in Europe. The following chart shows the overnight index swap market's implicit prediction for the European Central Bank's target rate by the end of this year. Three months into 2022, the prediction was that rates would not even get to be positive. Two weeks ago, sharply more hawkish language from the European Central Bank and some dreadful inflation numbers from across the region had pushed the prediction almost to 1.25%. Now, the market has decided that there will be two fewer hikes this year, rising to about 0.75%:  Financial markets that offer some of the clearest projections of inflation have also executed a reverse, although for them the ferret turned earlier in the spring. Inflation breakevens in the US, derived from the bond market, are now no higher than they were a year ago, despite all the horrible news on inflationary pressure that has hit since then. The big turn came about three months ago, and remains intact despite some inflation data since that has been genuinely shocking. Meanwhile, the Commodity Research Bureau Raw Industrials index, known as the RIND, which follows traded commodities that aren't available on the futures market and is regarded as a good pure measure of inflationary pressure in industry, has shown almost exactly the same picture. After surging consistently to hit an all-time high in the two years after the March 2020 shutdown, the RIND turned sharply southward:  Confidence in this new narrative means that ferrets reverse out the actions of central banks. Tuesday began with the Reserve Bank of Australia's decision to hike by a full 50 basis points. A 25-basis-points hike had been regarded as a possibility beforehand, so this would logically lead to higher bond yields. Quite the backtrack: Central banks should partly blame themselves for their lack of credibility, of course. And the speed of the cycle sparked by the Covid shutdown sends many calculations awry — that's how central banks find themselves hiking as investors are already sitting in a crouch for the next recession. But the problem is that the ferret doesn't get to reverse in a vacuum. As investors start to express that view in their buying and selling decisions, there are self-reinforcing outcomes. That means the RBA's monetary policy shift may be less impactful than intended. It's a sensible enough position to assume that inflation has already been adequately priced and to start worrying about a recession. But that change of position has consequences. For the ferret's biggest impact, look to oil and the dollar. The price of the world's most important commodity dropped below $100 per barrel as traders started to incorporate the notion of weaker demand ahead. Meanwhile, the dollar index, measuring the strength of the global reserve currency against a basket of the other most important major currencies, rose to its highest in 20 years, topping 106 index points. For most of the last few decades, the dollar and oil have been inversely correlated. This is largely because oil is denominated in dollars, and so any weakening in oil will make a dollar worth more, and vice versa. For example, the dollar surged in late 2014 as a breakdown in OPEC discipline allowed the oil price to tank. But that relationship has broken down in spectacular fashion over the last 12 months, with the dollar and oil surging together. That was obviously bad news for those who don't want a strong dollar (who also tend not to want expensive oil, either). On Monday, sadly for them, the traditional relationship resumed with the dollar gaining as oil fell: It's natural for the dollar to strengthen as commodity prices come down. It's also natural for oil to decline. As Harry Colvin of London's Longview Economics points out, the increase in the oil price accompanied a decline in inventories. Now that could reverse (ferret): There are evidently some very big political risks overhanging the oil price. But Colvin's summary of the bearish case makes a lot of sense: Surplus global oil production over the next 12-18 months is likely to reflect a mix of factors, including: (i) a gradual recovery in Russian supply (with an ongoing increase in exports to non-Western countries); (ii) a continued uptrend in OPEC output, led by core OPEC members (i.e. Saudi, the UAE, Kuwait, and Iraq, which have about 2.8 million bpd of spare capacity between them); (iii) ongoing production growth in other non-OPEC members (including the US, Canada, Norway, & Brazil); and (iv) a likely slowdown in global demand growth, probably to around 0-1% Y-o-Y growth (i.e. similar to that witnessed in prior global economic slowdowns, e.g. 2011/12 and 2015/16).

But how long can this carry on? It's fair enough to see oil as an overcrowded trade that is ready to fall — but the same is true of the dollar. This is how the respondents to the Bank of America Corp. monthly fund manager survey rated the most-crowded trades last month: Since that survey was taken, oil has fizzled, as might be expected. Those who were short U.S. Treasuries, in a bet that their price would fall and yield rise, have also been punished. But the consequence of getting out of commodities, and also of buying Treasuries, is to juice up still further the overcrowded trade in the US dollar. The problem is that the strong dollar creates problems elsewhere. As central banks fight inflation, they're already trying to mop up liquidity. Making less money available will help to rein in inflation and also slow the economy. As many around the world, particularly but not only in emerging markets, rely on dollar-denominated liquidity, this means that the reverse ferret on inflation converts into even tighter conditions outside the US — even though worries about growth should mean the opposite. The effect of the strong dollar on global liquidity is clear from this chart from London's CrossBorder Capital Ltd., which was compiled at the end of last week before the latest dramatic market moves: As ever, what matters is the change at the margin. In local currency terms, growth in the monetary base has dwindled and turned negative over the last three months; in dollar terms, the rate of contraction is twice as great, and liquidity growth has gone more sharply negative than at any time since the 2008 crisis. This is CrossBorder's summary: Latest weekly balance sheet data from major Central Banks show liquidity in local currency terms shrinking by around 10% (3m ann.). Liquidity expressed in US dollar terms is contracting at a much faster 23% rate (as evidenced by the stark divergence in the orange and grey lines in the chart alongside). The latter reflects rapid tightening by the US Federal Reserve starting from last December and the inexorable rise of the US dollar since early March. Year-to-date, the US unit has appreciated by 5% versus the yuan, 8% against euro, 10% versus the pound sterling and by a whopping 18% versus the yen.

Outside the US, the reverse on inflation is therefore driving a shift in policy that would only make sense if people were still convinced that inflation could only go higher. The ferrets have inflicted the greatest collateral damage, predictably, on emerging markets. Dollar-denominated emerging market debt has now rubbed out all its gains from the last five years, and is back to the lows during the horrors of the first Covid shutdown. US aggregate debt, which had been falling just as fast as EM debt during the months of the growing inflation scare, has parted company and is now rallying: That has been driven in large part by the currency market. The JPMorgan Emerging Market Currency index, a popular benchmark, has now dropped below 50 for the first time since it was initiated in 2010, when it was worth 100. Moves like this can have damaging and self-perpetuating effects: The pressure is accentuated by the way that currencies change investors' incentives. If you are based in a currency that weakens, international investment automatically grows more attractive. If you're denominated in a strong currency, there's little to be gained from going overseas. That tends to mean that money flows from currencies that are weakening into those that are already strengthening. This tends to deepen the effect. For an illustration, this is how non-US investments in dollars have performed since the beginning of 2020, compared to non-UK investments denominated in pounds.  The pound tanked below $1.20 Tuesday, a level it has only momentarily breached on a couple of occasions since 1985, when a very different world featured Margaret Thatcher in her pomp in Downing Street, and Paul Volcker still reigning supreme at the Fed. A good contrarian might surmise that this would be a good time to bet on a weaker dollar and stronger pound, but investment flows tend to be driven by performance-chasing. The odds are that those based in weak currencies will continue to use them to buy dollar-denominated assets. And so the ratchet continues to tighten for the emerging world, and even for Europe and the UK. Bulls and bears alike should look out for ferrets. Nobody on Earth seems to have a better idea how to survive than Boris Johnson. He has just withstood the resignations of his Chancellor of the Exchequer and health minister, along with a flotilla of more junior ministers. To use an analogy that the classically-minded Johnson might appreciate, this is the contemporary political equivalent of what Brutus, Cassius and their friends did to Julius Caesar on the Ides of March. You cannot carry on as prime minister if nobody will serve in your cabinet. But at the time of writing, Johnson has not fallen on his sword and instead found people willing to replace the resigners, Rishi Sunak and Sajid Javid. Moreover, he's done so after some spectacularly cynical negotiations. Nadhim Zahawi is now widely reported to have given the prime minister an ultimatum: Either he was promoted from education secretary to chancellor, in which he case he would accept, or he would quit the cabinet and follow Sunak and Javid in protesting Johnson's leadership. Apparently this was a gambit after Johnson's own heart.  It takes a special kind of nerve. Photographer: Chris J. Ratcliffe/Bloomberg All of this happened after Johnson was caught — yet again — in a lie, and the civil servant who formerly headed the Foreign Office wrote a public letter to denounce him. The resignations are not about ideological principle, but about revulsion at the notion that someone can behave this badly and continue to hold the most powerful office in the country. It's a revulsion I share. But I do envy anyone with the raw nerve, thick skin, and sense of entitlement that are needed to press on in a position like Johnson's. Life must be very different for people who can lie with a straight face, bear the embarrassment when they are found out, and then carry on as though nothing had happened. I've linked to a musical piece, premiered before he took office as prime minister, that homed in on this aspect of Johnson's character. It's not a new discovery. For more reading and background, I'd like to recommend this piece by my old mentee Simon Kuper, who was a few years behind Johnson at Oxford. A lot about the current behavior we're witnessing at the top of the UK can be attributed to the way people were able to behave in 1980s Oxford (where I was two years behind Johnson and three years ahead of Kuper). Simon's book on this, Chums, is fascinating. And for my own take, written in late 2018 as the Brexit process was breaking down into disorder, try this.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close.

More From Other Writers at Bloomberg Opinion: Want more from Bloomberg Opinion? Terminal readers head to {OPIN <GO>}. |

No comments:

Post a Comment