| ESG is in trouble. For proof, look no further than the Bloomberg Opinion headline "The Virtue Bubble Is About to Burst. Good Riddance." that appeared earlier this week over an excellent piece by Allison Schrager; or to the comments in an interview with David Westin on Bloomberg TV by Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock Inc. and the world's chief ESG-vangelist, that he doesn't want the private sector to be "environmental police"; or the news that the head of Deutsche Bank AG's DWS fund management unit had been toppled after a police raid looking into alleged "greenwashing"; or the suspension of the head of responsible investing at HSBC Asset Management, my old colleague Stuart Kirk, after he spoke not wisely but too well about how "climate risk is not a risk we need to worry about"; or the furious reaction of Elon Musk to the news that S&P Global no longer rated his Tesla Inc. as an ESG stock. All this evidence of industry concerns comes amid signs that the consumer is also now growing a little more leery about ESG investing. According to State Street Corp., one of the biggest three providers of exchange-traded funds, its ESG ETFs suffered an outflow of $1.9 billion in May, the greatest since the products came on the market, and the first outflow of any kind in three years. And Bloomberg Green also reports that pressure on ESG asset managers from clients is growing.

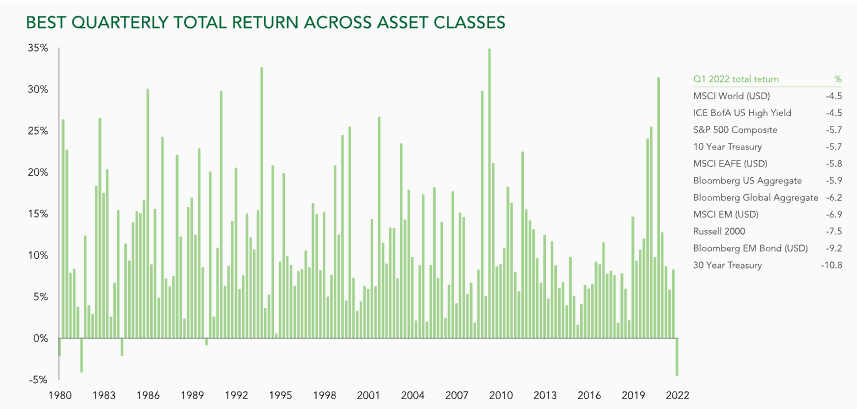

None of this means that the concept of investing based on environmental, social and governance principles is over, and none of it is particularly new. The S (Social) and the G (Governance) have long been ambiguous and the efforts of different ratings companies to distill them into simple measures that can be used for indexes have been almost comically contradictory. The same company can have a top rating with one and a bottom rating with another. Bloomberg won a Wincott award this week, I'm proud to say, for a great dissection of how ratings by MSCI Inc. really work. This cuts to the heart of the attempt to organize passive investing on ESG principles, or offer investors the chance to have their cake while still feeling virtuous. If ESG concepts are too subtle for that, and they probably are, then the effort to rebrand much of the passive investment industry must fail. Beyond S and G, on the core issue of the environment ("E"), concern is growing that ESG investment is a blunt instrument. Showering capital on alternative energy while withholding it from traditional operators may well have contributed to the surge in the oil price this year. This is a perilous transition to manage, and passive investment isn't the way to do it. Meanwhile, the concept of "stewardship" or "engagement" is also vexed; how exactly can we trust a few asset managers to throw their weight around? At one point the notion was that this was a painless way to use capitalism itself to make a long-run transition, while government planning would be harder. Now, as Fink says, there's a growing grasp that there's also a need for the kind of planning that comes from governments staffed with technocrats. Markets and planning seldom mix. Much of this is an understandable overreaction to the understandable over-praise that the concept enjoyed for many years. It also reflects the growing realization that ESG only seemed to be such a good idea because it delivered great returns. At first, with big money flows being directed into places that hadn't received so much capital before, ESG was almost a self-fulfilling prophecy. A big element of its success to date, it now becomes apparent, is good old-fashioned return-chasing. Another major element is the "quiet life" faction; present ESG as a passive investment that makes the same returns as a normal benchmark index, and many trustees will switch to it just to head off angst from their clients, particularly in universities or the public sector. None of this means that it's over. ESG remains alive and well, but now it is strongest in the heart of the US government, rather than out in the private sector. Bloomberg Government reports that new nominees to the Federal Retirement Thrift Investment Board, which oversees a big federal pension fund, have written to three Republican senators saying: "We agree it is unfitting for Americans to invest in companies from China or elsewhere that undermine US national security." This has been a bipartisan cause celebre, with the Republican senator Marco Rubio joining with Democrats to try to force the fund to divest from Chinese companies that could be considered a security risk. The cause has survived a change of government, and it remains intact even as the Biden administration tries to retreat from the trade tariffs levied on Chinese imports under Donald Trump. These days, what you might call "capital protectionism," or to give it a more positive branding ESG, is more effective. The ESGenie is out of the bottle. Indexers are powerful, as the desperate efforts by the Chinese government to persuade MSCI to include A shares in its benchmarks makes clear. And when you invest with passive indexes, it's easy to start making exclusions. Once exclusions are made by someone, they become habit-forming for the rest of the herd. Although the reaction against ESG is well underway, it has provided the blueprint for what could be a very dangerous move to unpick globalization. Just how difficult has this year been if you had assets to allocate? Really, really bad. If you're an asset allocator having a tough time of it, you can at least comfort yourself with the knowledge that this has been a historically bizarre year so far. Here are two exquisitely painful illustrations. First, Ruffer LLP offers this chart which on a quarterly basis takes the best return from a range of 11 different global indexes of stocks and bonds. The chances that at least one of the 11 will have gained in any quarter are overwhelmingly high. After all, when investors sell something, they have to put the money somewhere else. The first quarter of this year, it turns out, was the first in more than three decades when none of them gained. If you're sticking to broad indexes of stocks and bonds, there's been nowhere to hide:  Cryptocurrencies were not on the list, and would not have helped. The overriding factor driving markets was inflation, with the attendant upward pressure on interest rates. And that had a negative effect on almost everything. As in 2008, when investors thought they had diversified by holding commodities and emerging markets, it turns out that buyers of stocks and bonds were just making the same bets in different places. This is how Duncan MacInnes of Ruffer put it: The best case scenario for stock and bond investors was a -4.5% return from high yield bonds. Everything else was worse. Equities, sovereign bonds, corporate bonds, infrastructure, property, private equity, private credit, venture capital and cryptocurrencies all posted negative returns. There was nowhere to hide – and that is before adjusting for the 7% inflation ravaging your capital. We have called this the illusion of diversification. The balanced portfolio was not balanced. The assets investors believed to be diversifiers turned out to have higher cross-asset correlations than first thought. They all appear vulnerable to the same risks – rising interest rates and rising risk premiums, which both appear to be happening at the same time. The only place to hide in conventional assets was commodities.

Note the extraordinary fact that in an environment of rising rates the investment that held on to its value the most was the debt of companies with particularly weak credit. Here is another demonstration of the problem, from the BlackRock Investment Institute, putting the performance of global bond and stock indexes on a grid. Not only has there been no good performer this year, but the losses for bonds have been horrific: Looking to illustrate what's happening myself, I tried graphing the broad commodity indexes published by Bloomberg and by S&P Global, against the MSCI All-World stock index and Bloomberg's global bond aggregate index. Usually, concentrating on calendar dates such as the turn of the year is a mistake, but this time, the big turning point really did come at the new year. It was at that point that stocks turned down, accompanied by bonds, while commodities enjoyed a rally, however they were measured: Can this continue? The answer is almost certainly "no," unless true stagflation lies ahead. Were commodity prices to continue to surge, it would grow that much harder to contain inflation. Higher prices would compress demand, as would higher interest rates from central banks. As this is a very negative scenario, this year's asset performance to date has been nightmarish in more than one way, then. On the positive side, looked at this way it's clear that the nerves of the last few weeks haven't changed the basic fact that markets are positioned more for stagflation than anything else. If you think that a recession is imminent, there's an opportunity in bonds; if you think central banks can actually achieve a soft landing, then there's an interesting opportunity in stocks — although the still very rich valuations in the US will compel some selectivity.  | If there's anyone who knows a thing or two about survival, it's Queen Elizabeth II. My monarch for my entire lifetime, and for the great majority of citizens of Britain and the Commonwealth, her longevity has been as remarkable as her ability to keep republicanism off the agenda. There are plenty of anti-monarchists in British life. Yet there hasn't been the faintest spark of an attempt to come up with a workable republic to replace the monarchy. That would involve writing a constitution for the first time, and deciding how much power to vest in a president and how to choose them, and work out how they could ever gain the symbolic power and authority of the monarch (or of the American president). The Brexit vote showed that Brits cared a lot about democracy, as they should — which would imply that a continuing hereditary monarchy was an even greater problem than membership of a federalist Europe. The problems implementing Brexit, however, are probably a picnic compared to replacing the queen, which is one very big reason why people haven't tried to do it. For all of my lifetime it's been possible to put off such difficult discussions because it's been obvious that the monarch has public support. If put to a referendum, the monarchy would survive. Whether that will still be true once she finally departs the stage is another matter entirely. So I suspect we should be thankful she's still around. Her position is an anachronism and an anomaly and yet somehow she has made a success of it. It's little appreciated how much she has changed over time. Take a look at how she's been portrayed on film by Emilia Fox, Helen Mirren, Claire Foy and Olivia Coleman. There's a rundown of the actresses to take the role here. However I do get the impression that this jubilee is less of a big deal for the country than the Silver Jubilee in 1977, when it dominated everything for months. That's best remembered now for the Sex Pistols' God Save the Queen, which stalled at number two in the week of the jubilee. Have a great week everyone, and enjoy the street parties in Britain. More From Other Writers at Bloomberg Opinion: Want more from Bloomberg Opinion? Terminal readers head to {OPIN <GO>}. |

No comments:

Post a Comment