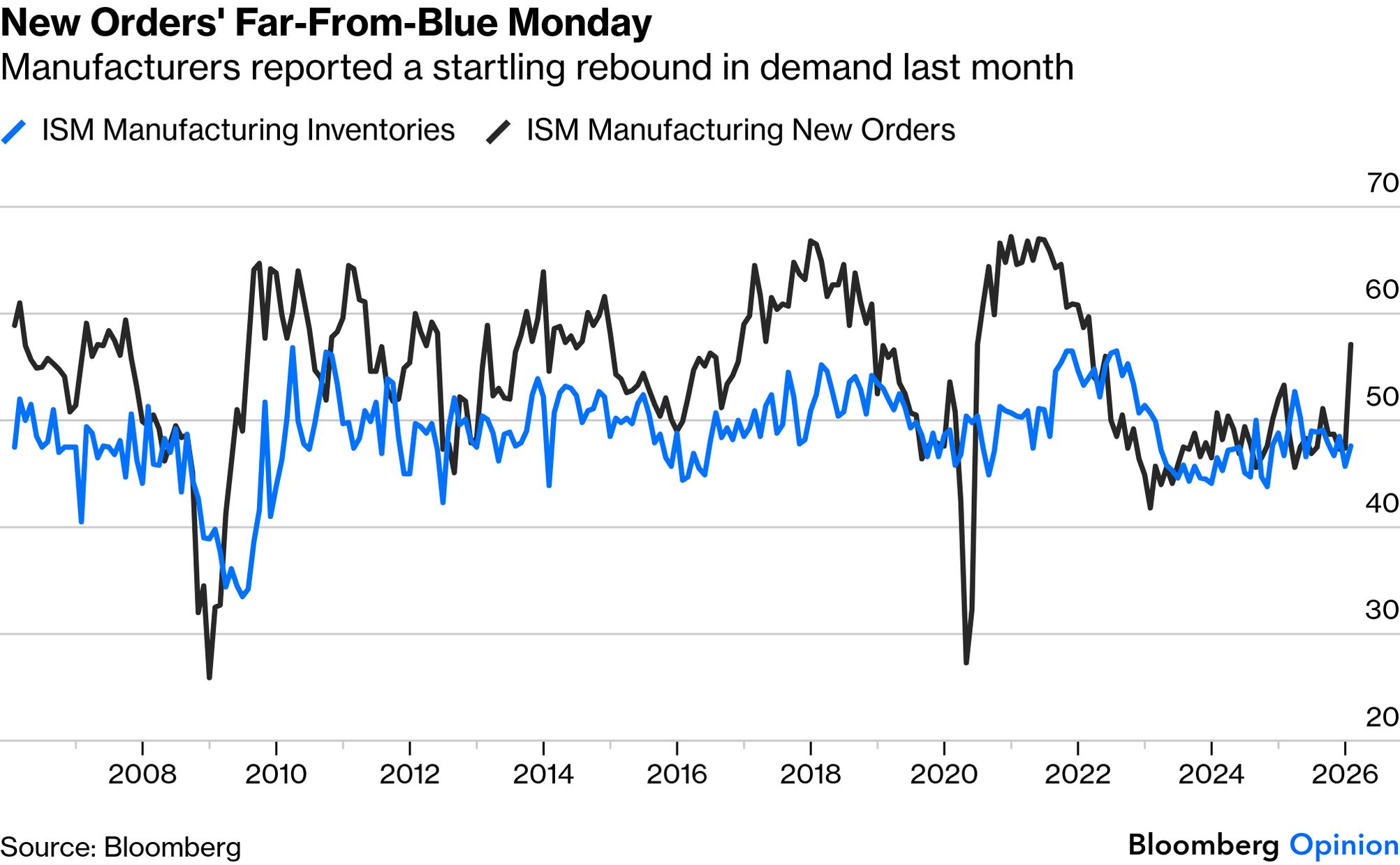

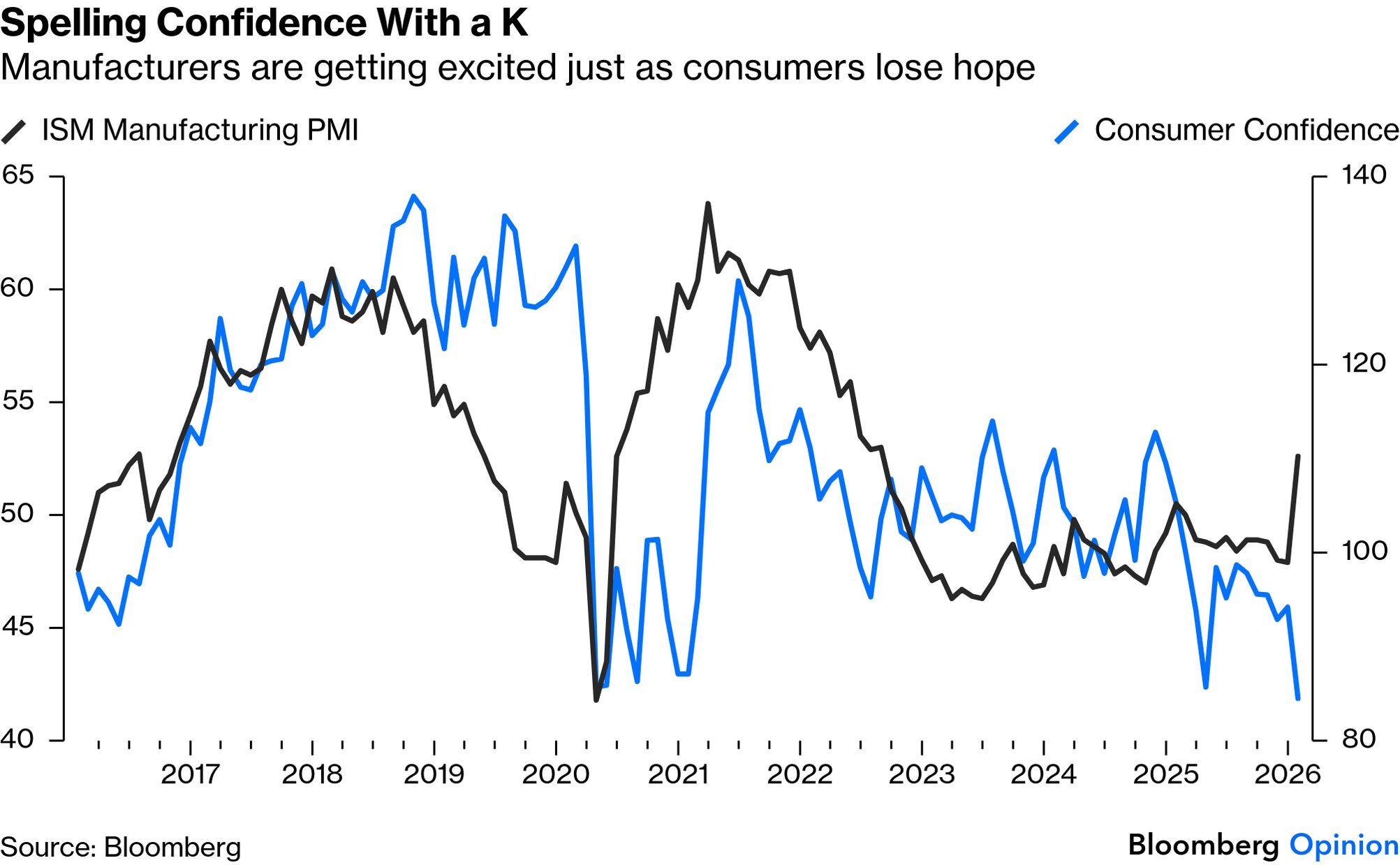

| Nobody's perfect. But taken in isolation, the latest US economic numbers look pretty close. The Institute for Supply Management's survey of manufacturing, long a reliable economic leading indicator, has been signaling for years that the sector is slumping. It came as a bona fide surprise to see its measure for new orders shoot up last month, putting it now far ahead of inventories. It's one month's data point, but it certainly looks like the beginning of a true cyclical restocking boom: The overall number was the strongest since the Federal Reserve started tightening early in 2022. Earnings and the entire global stock market have been suggesting something like this is afoot; this is one of the clearest confirmations yet from the mainstream data. That said, it maintains another trend — the views of manufacturing executives and consumers (as measured by the Confidence Board) are diverging and forming a perfect K-shape: There are caveats. The Conference Board suggests that consumers feel even worse than they did during the worst of the pandemic lockdowns, which is startling to say the least. Other surveys, such as the University of Michigan's, show poor confidence, but nothing as bad as this. The notion of a recovery that many don't feel — with gains for some balanced by a downturn for others — seems stronger than ever. Peter Atwater, the behavioral economist who originated the K-shaped economy during Covid to signify a bifurcated recovery, suggested that the latest data might be distorted by ripple effects from last year's government shutdown. But the overall picture emerging makes sense: This reflects the relative confidence of business managers and asset owners versus folk who don't own assets. If you looked at portfolios in January, more or less everything was at records. If you owned anything you felt great.

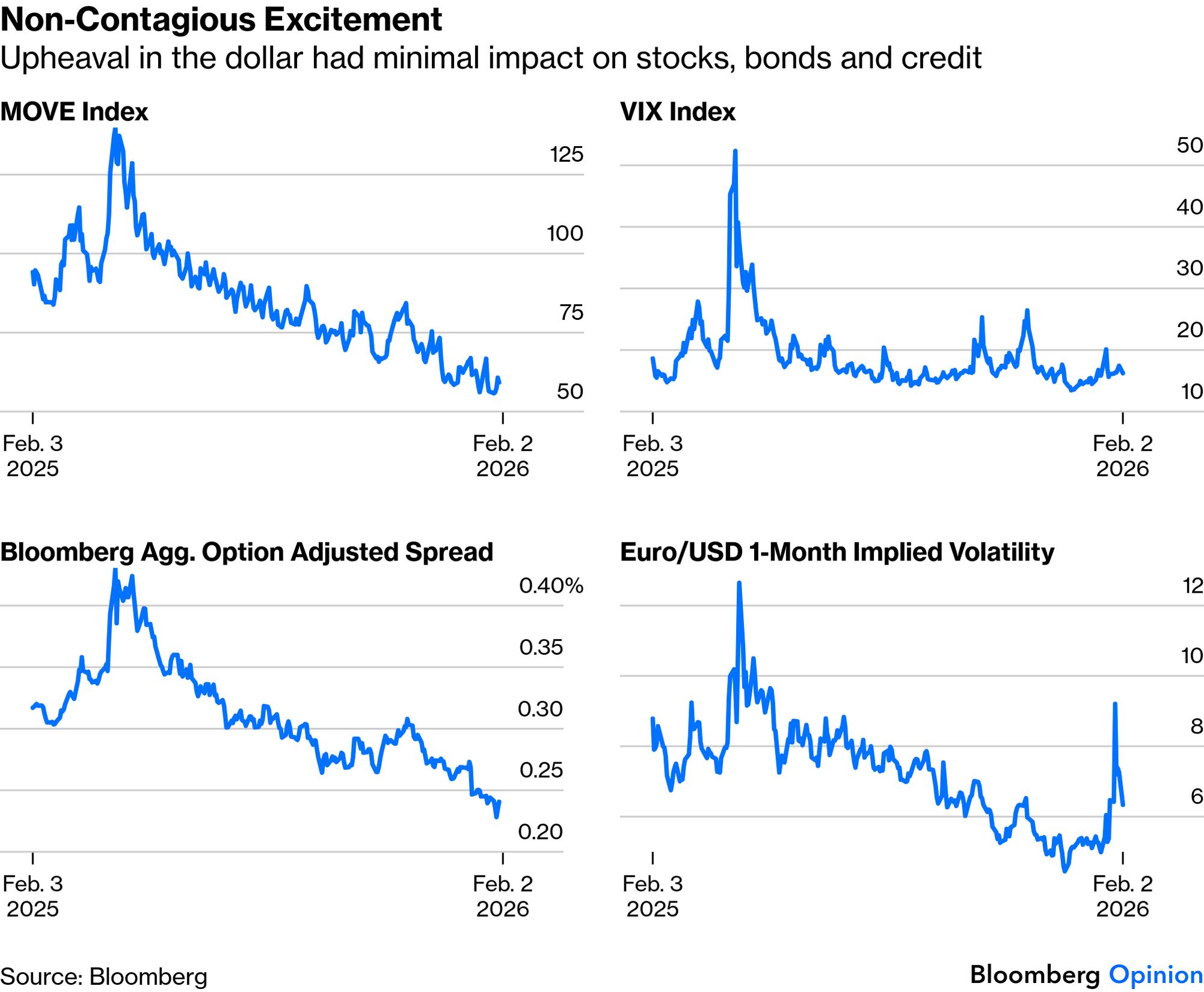

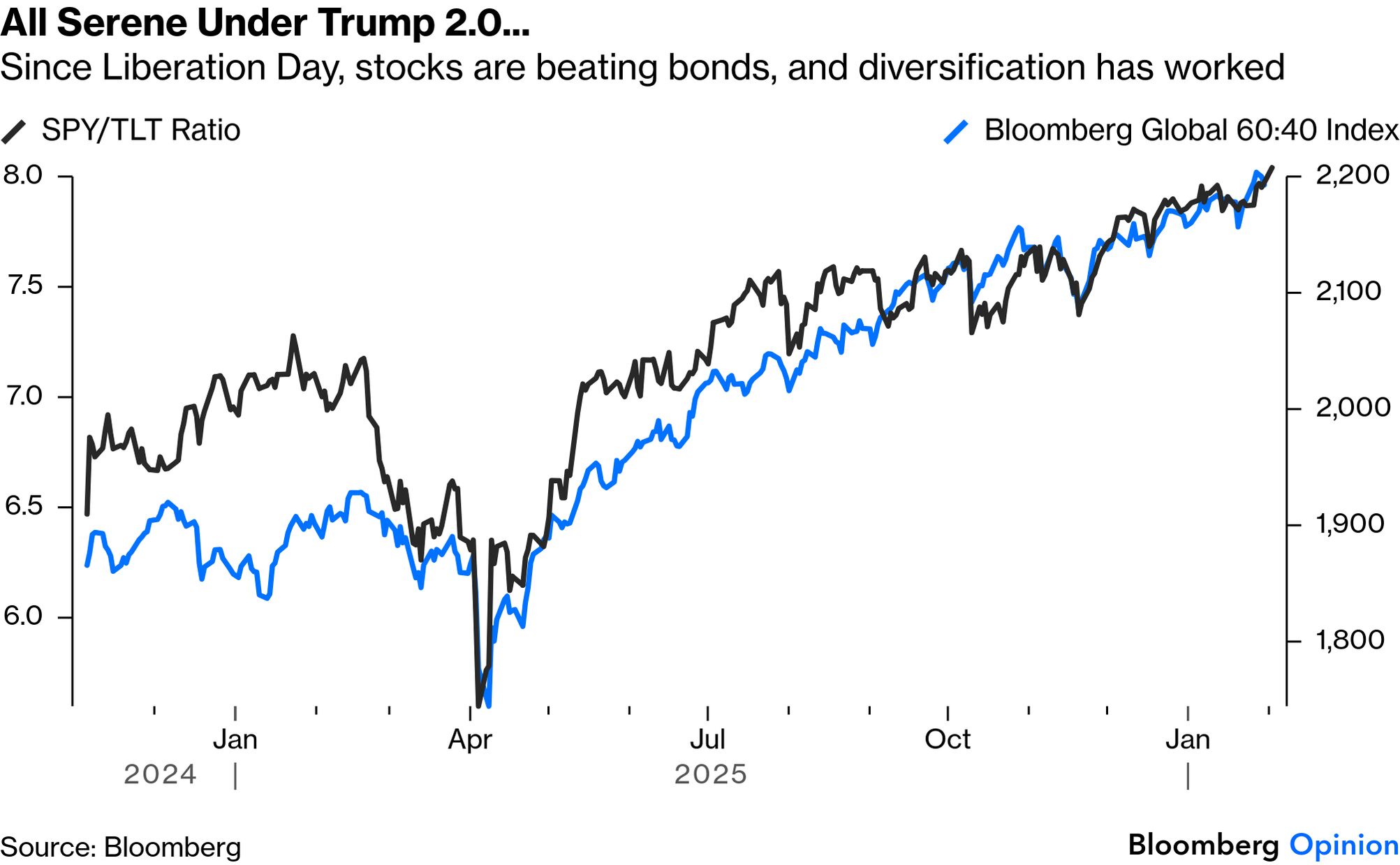

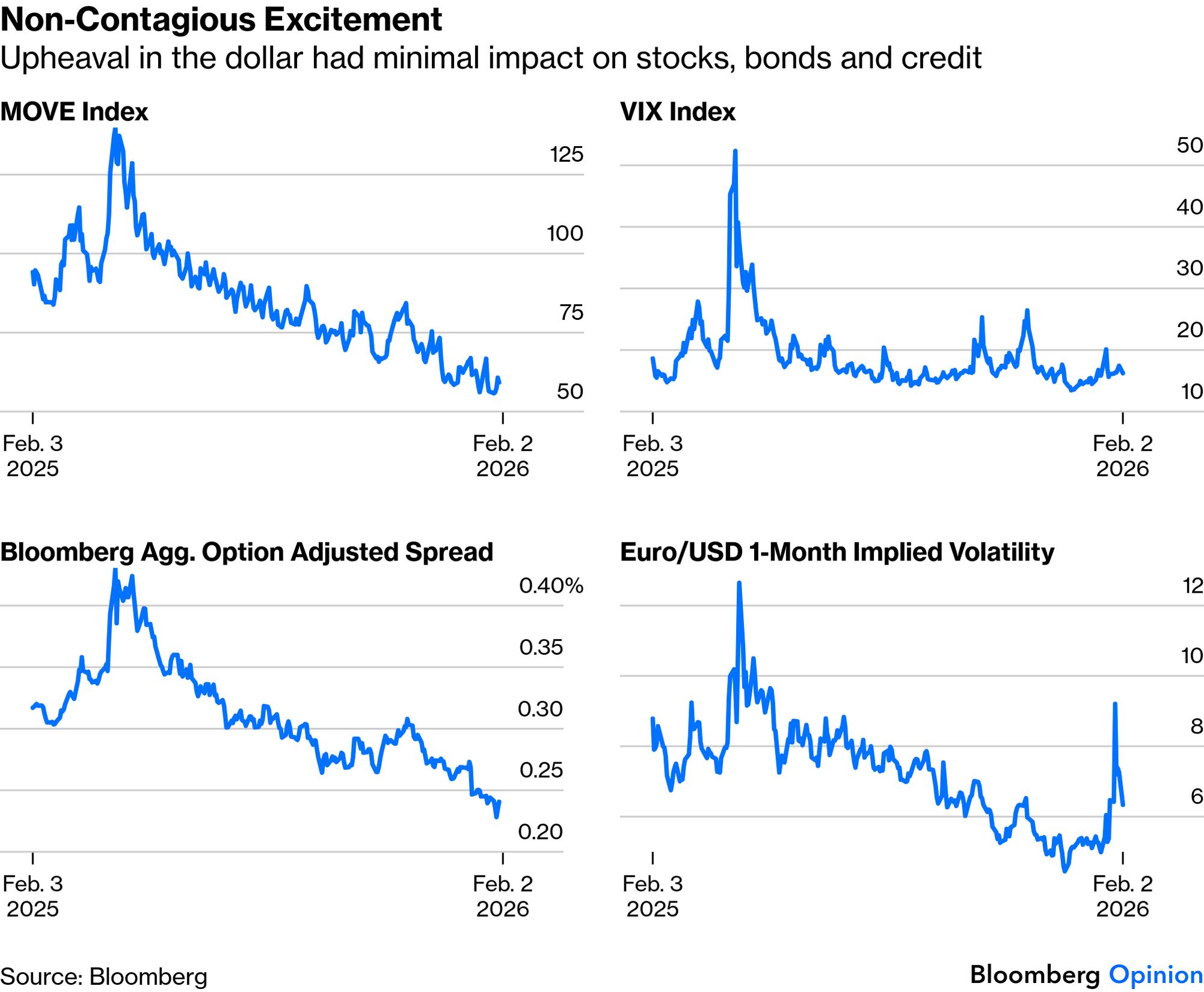

And indeed, making more money has been easy of late for those who already have some. Equities have steadily beaten bonds (as proxied by the main exchange-traded funds for the asset classes) while a boring diversified portfolio of 60% stocks and 40% bonds has done just fine: This isn't, evidently, how it feels for miserable consumers. It's also hard to square with a remarkably hectic month that brought the capture of Venezuela's Nicolas Maduro, insurrection in Iran, the attempted annexation of Greenland, and death on the streets of Minneapolis, and concluded with the biggest one-day crash for precious metals in history. But outside of the dollar and gold, where volatility has spiked, other asset classes have been serene. Volatility in bonds (shown by the MOVE index) has fallen steadily since Liberation Day, credit spreads are at their tightest since the Global Financial Crisis, and equity volatility remains contained:  It seems as though the burst bubble in gold and the dollar meltdown, lynchpins of the global financial system, have been treated like trees that fall in the wood and nobody hears them. This is in part because buying from China has driven gold. It's also because for now the US economy is growing in a way that supports corporate earnings beautifully. With growth like this, Fed interest-rate cuts seem a little less urgent, and credit and equities can continue cruising swan-like across the surface, even with much effort going on beneath. A problem with this is that we need the swan-like glide to continue. Doug Peta of BCA Research warns that consumption growth has outpaced the rise in disposable household income (and triumphed over the negativity in the confidence surveys). It's hard to attribute that to anything other than the portfolios of those who hold assets: The hoi polloi are not borrowing to bridge the gap, consistent with consumer credit's lessened sensitivity to interest rates following the financial crisis. Although the concentration of equity ownership continues to increase, our analysis of disaggregated household balance sheets suggests that brokerage accounts are the most likely funding source.

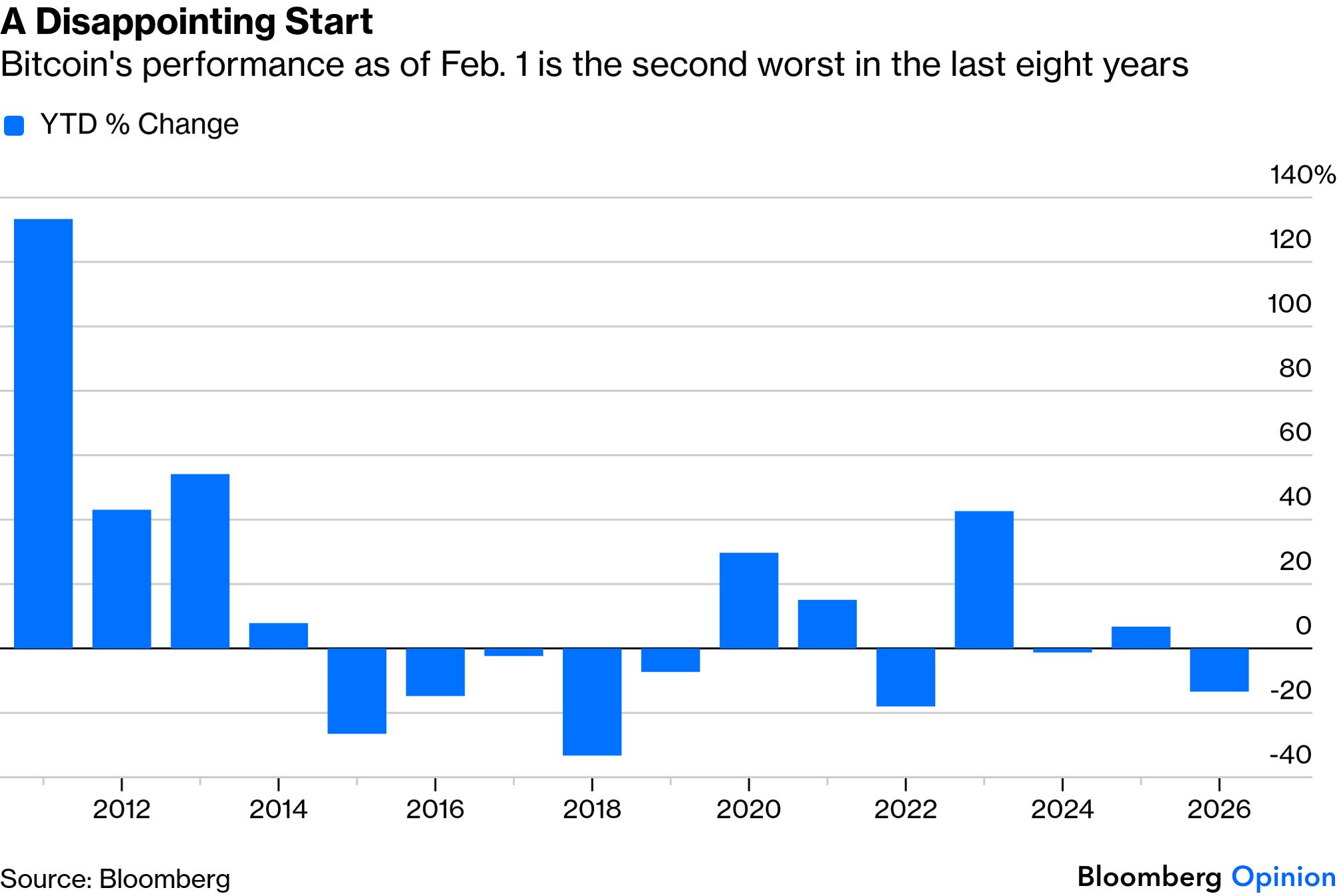

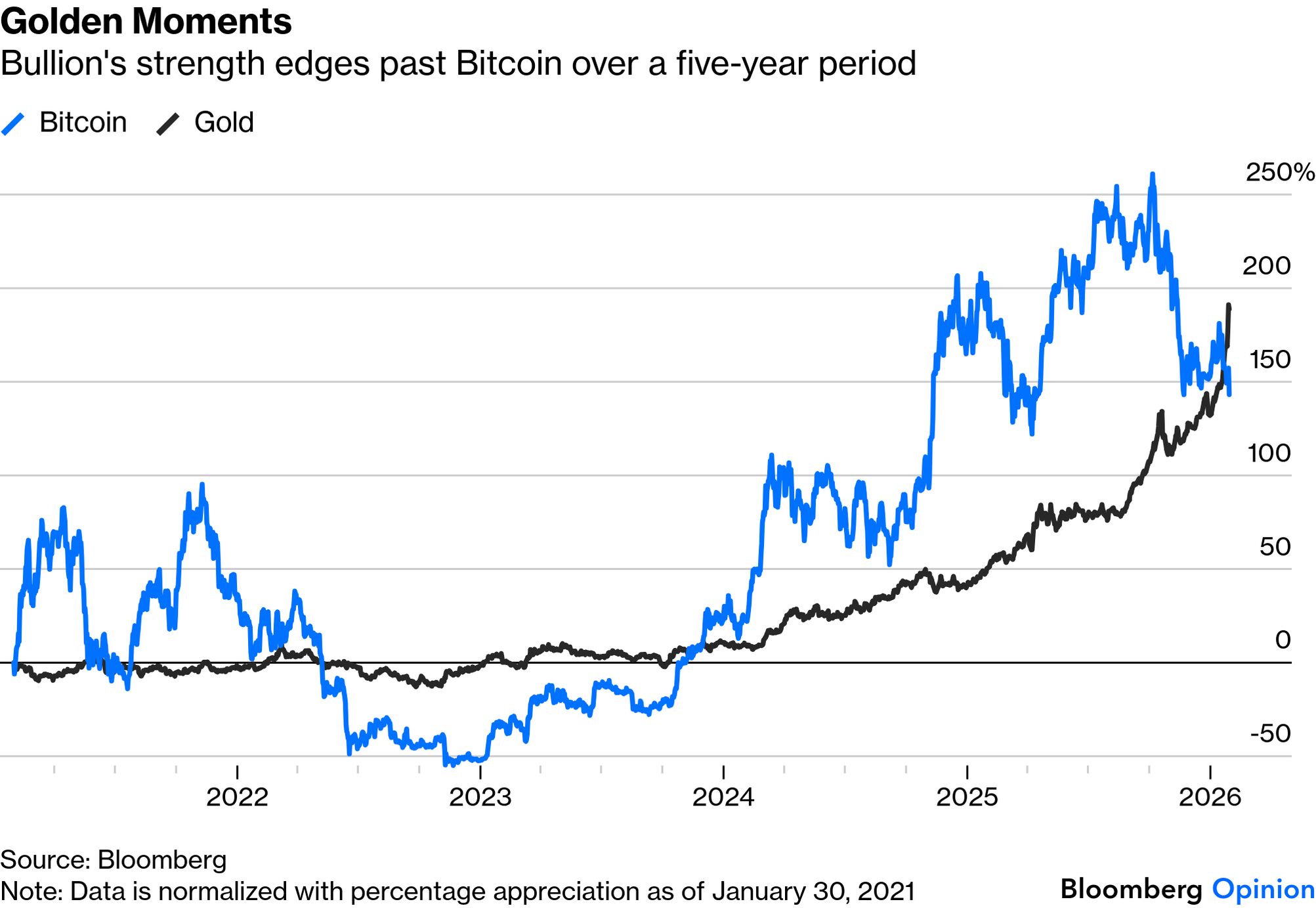

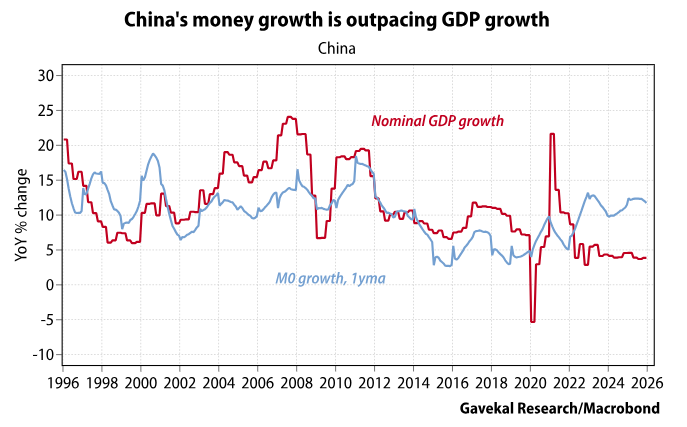

In other words, the people on the top bar of the K are helping to drive a cyclical rebound with the profits they have made. The equity tail, to use Peta's phrase, may be wagging the equity dog. Kevin Warsh's nomination to the Fed chairmanship hasn't caused much dismay in equities, which had a strong Monday. But he may need to keep it that way, as the economy looks ever more leveraged to the K-shaped equity rally. In the past, he has criticized the Fed for "prioritizing long-term growth over fleeting market stability, temporary stimulus and market manipulation." He also has a perhaps slightly alarming endorsement from the renowned bearish strategist Albert Edwards of Societe Generale SA, who once praised Warsh for his warning that the Fed had become "the slave of the S&P 500." Warsh, without doubt, wants to win the central bank's release from its obligation to prop up the stock market, but that looks very challenging. Meanwhile there's another intriguing exception to the appetite for risk in crypto… Bitcoin's recent record is the antithesis of its supposed status as the quintessential risk-on asset. Since its October peak, the so-called digital gold has plunged by more than 40%, bringing the rest of the crypto market with it. Its year-to-date loss of 10.5% — when enthusiasts had expected a regulatory tailwind — is a source of deep frustration. It hasn't started a year so badly since 2022, when the Fed was readying one of the most aggressive tightening cycles in its history: Bitcoin's cough has infected other digital assets with a terrible cold. The poor run, especially when set against gold's performance, is striking. It's hard to draw parallels between the two assets as credible hedges against currency debasement. The shiny metal may have just taken a plunge, but it has still fared far better than Bitcoin, which was invented for uncertain times like these: Why is this happening? Gavekal Research's Louis-Vincent Gave points to differences between the US and Asian liquidity environments when talking about the divergence between crypto and precious metals. Crypto is more sensitive to shifts in US liquidity while precious metals benefit from the recycling of Asian capital, particularly in China, where Bitcoin trading and mining have been prohibited since 2018. That money has to go somewhere, and so it is poured into gold: Until Warsh's Fed chair nomination, gold and Bitcoin were headed in different directions as traders retreating from the token reallocated to precious-metals funds. Such funds absorbed $1.4 billion in fresh inflows, while Bitcoin-linked products suffered roughly $300 million in withdrawals on Thursday as the selloff gained strength. Perhaps more alarmingly, the post-Warsh rout in gold and silver might by this logic have released money back into crypto, but Bitcoin disintegrated further over the weekend. Bitcoin has already been through several winters, and summer always returned. Arca Investments' Jeff Dorman laments that "the good years for crypto investing seem like ages ago." He doesn't offer any great reassurance for crypto enthusiasts: Back in 2020 and 2021, it seemed like there was a new narrative/sector/use case and a new type of token every month, and positive returns came from many corners of the market. While blockchain's growth engine has never been stronger (on the heels of Washington legislation, the growth of stablecoins, Decentralized Finance (DeFi), and real-world assets tokenization), the investment environment has never been worse.

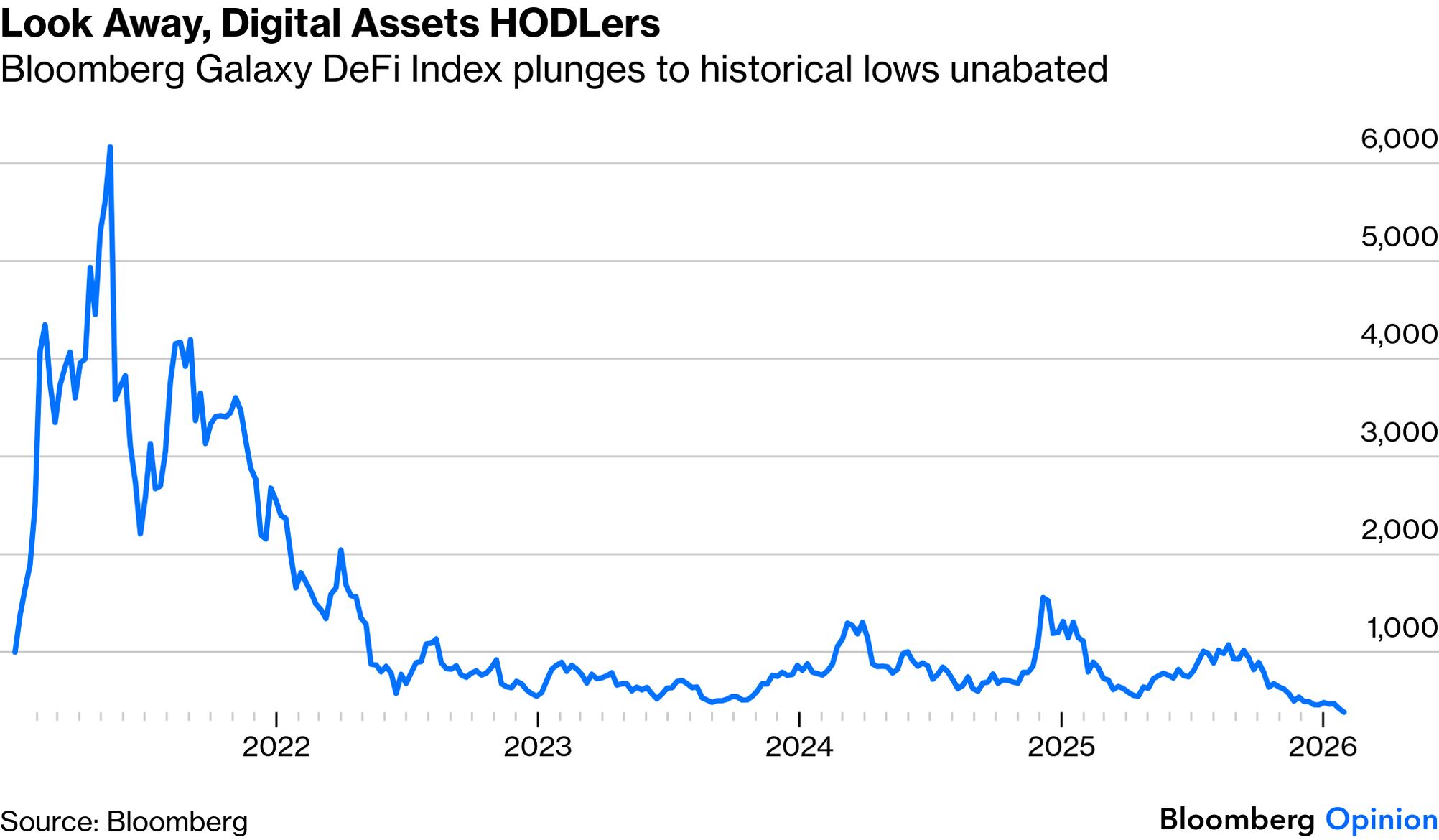

The problems extend far beyond Bitcoin. This is how the Bloomberg Decentralized Finance (DeFi) Index — which measures digital assets offering financial services — has performed since inception at the end of the pandemic: Dorman traces the crypto market's health five years ago to wide dispersion and weak inter-market correlations. A diversified portfolio, he points out, actually smoothed out returns and often lowered overall risk. Liquidity came and went according to interest and demand, but returns were mixed, which was very encouraging. In that environment, inflows into crypto hedge funds made sense, supported by a growing investable universe and genuinely differentiated returns. A lot has changed since then: Fast forward to today, and the returns of all crypto-wrapped assets look identical. Since the flash crash on October 10th, downside returns across sectors have looked indistinguishable. It doesn't matter what you own, or how the token accrues economic value, or what the trajectory of the project is … the returns are largely the same. This is very discouraging.

It's tempting to conclude that crypto has lost its mojo. But that would be premature, given the last year's raft of crypto-friendly legislation. The identity crisis does little to reassure enthusiasts, much less attract new investors, and even the most-ardent HODLers (Hold On for Dear Life) would admit a recovery looks a tall order. But it's not impossible. -- Richard Abbey |

No comments:

Post a Comment