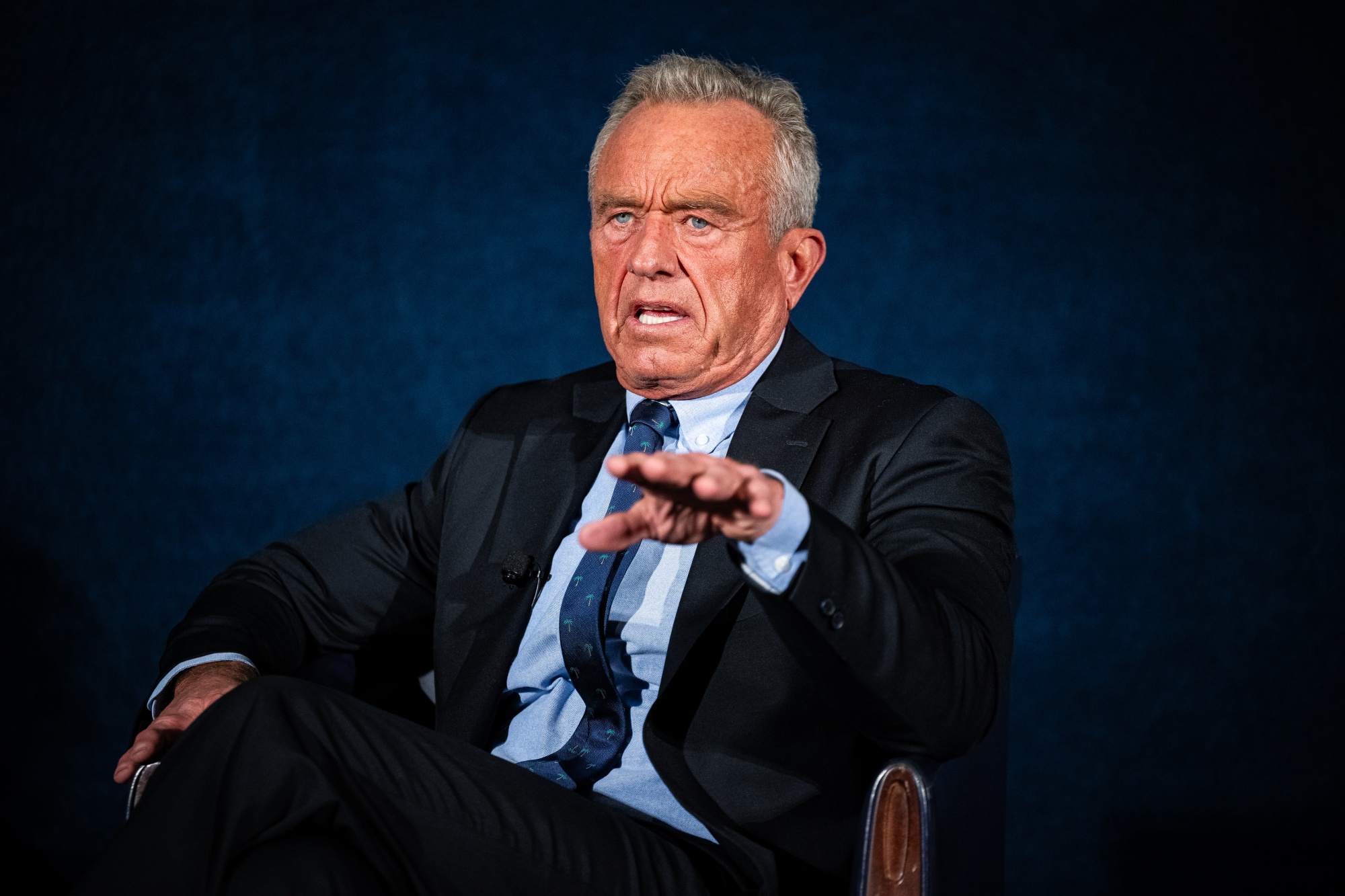

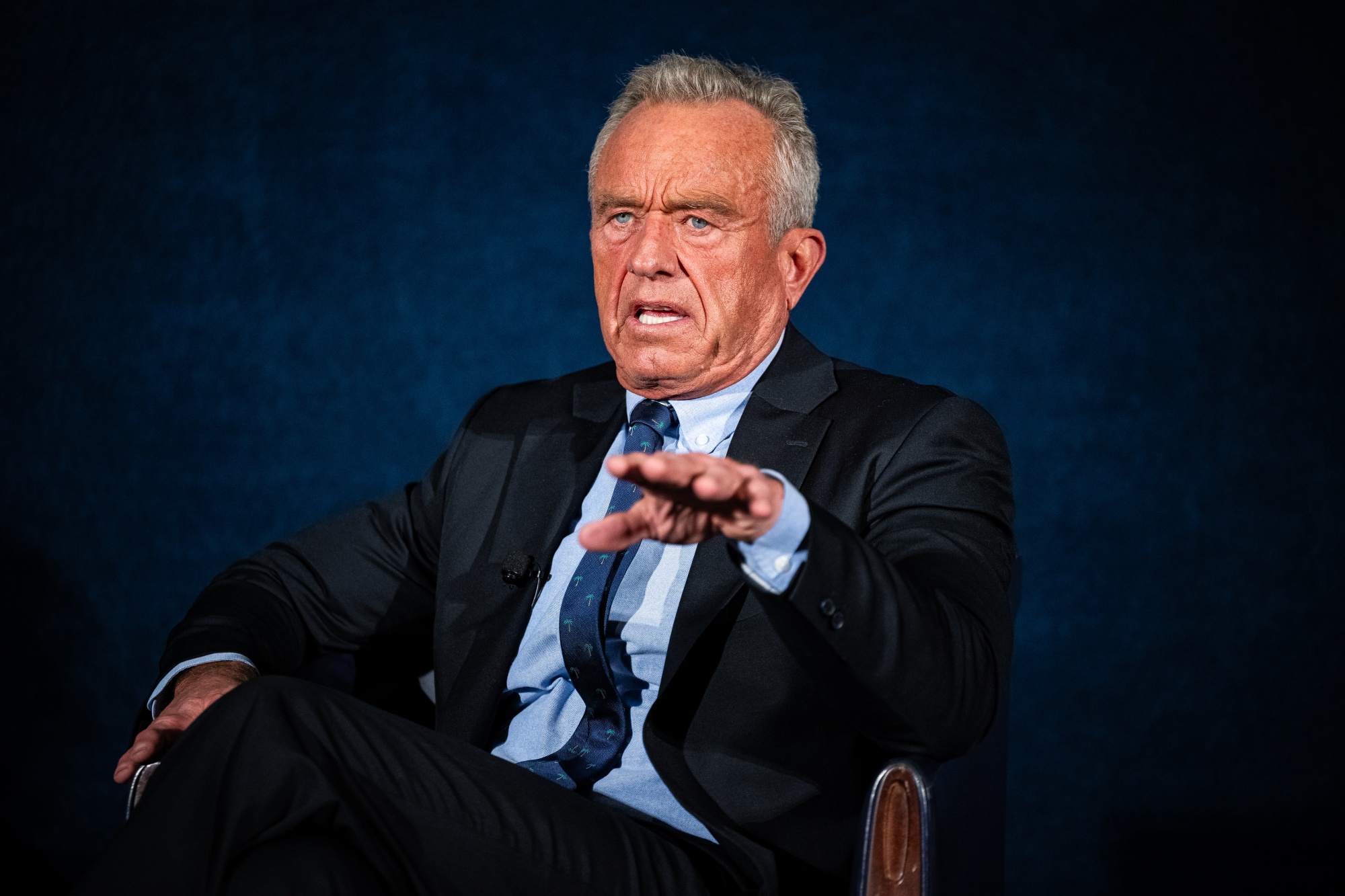

| The highly contagious measles virus has gripped the US again, decades after it was eliminated through a mass vaccination campaign. Bloomberg News health reporter Jessica Nix writes about the outbreak in South Carolina that shows no signs of slowing down. Plus: Microsoft's game studio Obsidian is on a cost-cutting mission. If this email was forwarded to you, click here to sign up. Hundreds of people in quarantine. School and church exposures. Measles is tearing through the northern part of South Carolina, and there's no signs of the outbreak slowing down. The highly contagious measles virus was first reported in the Spartanburg County region in October. The area is home to many eastern European immigrant families who are largely hesitant of vaccinations because of a general distrust in institutions. In four months, measles has spread rapidly and exposed people at religious services, grocery stores, dozens of local schools and two universities. The outbreak reached 876 people as of Tuesday—the majority of whom are unvaccinated children—marking the largest outbreak in the US since 2000. Medical experts say 95% of a community must be vaccinated to achieve herd immunity and sharply curb the spread of a virus. In South Carolina, 92.1% of kindergartners have both doses of the measles, mumps and rubella immunization. Those 3 percentage points make a huge difference. In spite of that and the high rate of infections, the state hasn't asked for on-the-ground support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. State epidemiologist Linda Bell has said it hasn't done so because it has enough people working on contact tracing and vaccination campaigns. Left unsaid: Robert F. Kennedy Jr.'s Department of Health and Human Services has been, if anything, working to undermine vaccine confidence. Ralph Abraham, the CDC's new principal deputy director, recently endorsed the MMR vaccine on a call with reporters but emphasized it's a personal choice for families.  Kennedy. Photographer: Graeme Sloan/Bloomberg Pediatricians say the US should do more to persuade hesitant communities. Martha Edwards, retired pediatrician and president of South Carolina's chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics, rejects the "personal choice" argument. "When it's up to the parents, you're making the decision not just for your child, but for the child's community as well," she says. Last year, when a measles outbreak was ravaging a Mennonite community in West Texas, three people died; two were unvaccinated children—the first measles-related deaths in almost a decade. After that, the CDC recorded dozens of other outbreaks across 44 states in the US in 2025, leaving the final tally for infections at 2,267—a three-decade high. Nearly all of the cases were among unvaccinated people. Texas was able to end its outbreak in August after a mass vaccination campaign, especially in countries surrounding the epicenter in Gaines County. The state called the CDC to send a team of epidemiologists to work with local public health departments and reach vaccine-hesitant communities. Still, vaccination rates for measles have fallen below the herd immunity level nationwide. Cases in North Carolina and Washington state have been linked to South Carolina. It's created a perfect storm that could see the US losing its measles elimination status when the Pan American Health Organization's subcommittee on measles elimination analyzes epidemiological data in April. (A country can lose its status when there's a continuous chain of spread for one year or if the group decides the nation doesn't have adequate public health strategies to keep the virus controlled.) Just last month, the CDC recorded almost 600 cases, the majority of which were among the unvaccinated and at a pace far outpacing the rate of infections from a year earlier. No vaccine is perfect, but MMR is 97% effective after two doses in preventing an infection and has been repeatedly proved to be safe. In South Carolina, claims for religious and medical exemptions from vaccines have increased in recent years, and the state's Department of Public Health has said people aren't getting vaccinated fast enough. Free vaccination clinics are seeing little foot traffic. The state has reported 18 hospitalizations, though hospitals aren't required to disclose the data, meaning the number could be higher. Meanwhile, South Carolina's exposure rate remains high. "We are not seeing that slowing at all yet," state epidemiologist Linda Bell said on a call with reporters on Jan. 28. According to Edwards, the likely outcome at this point is bleak: "Every unvaccinated person in South Carolina gets measles, and then it'll end," she says. "I can't imagine another way that it can end." |

No comments:

Post a Comment