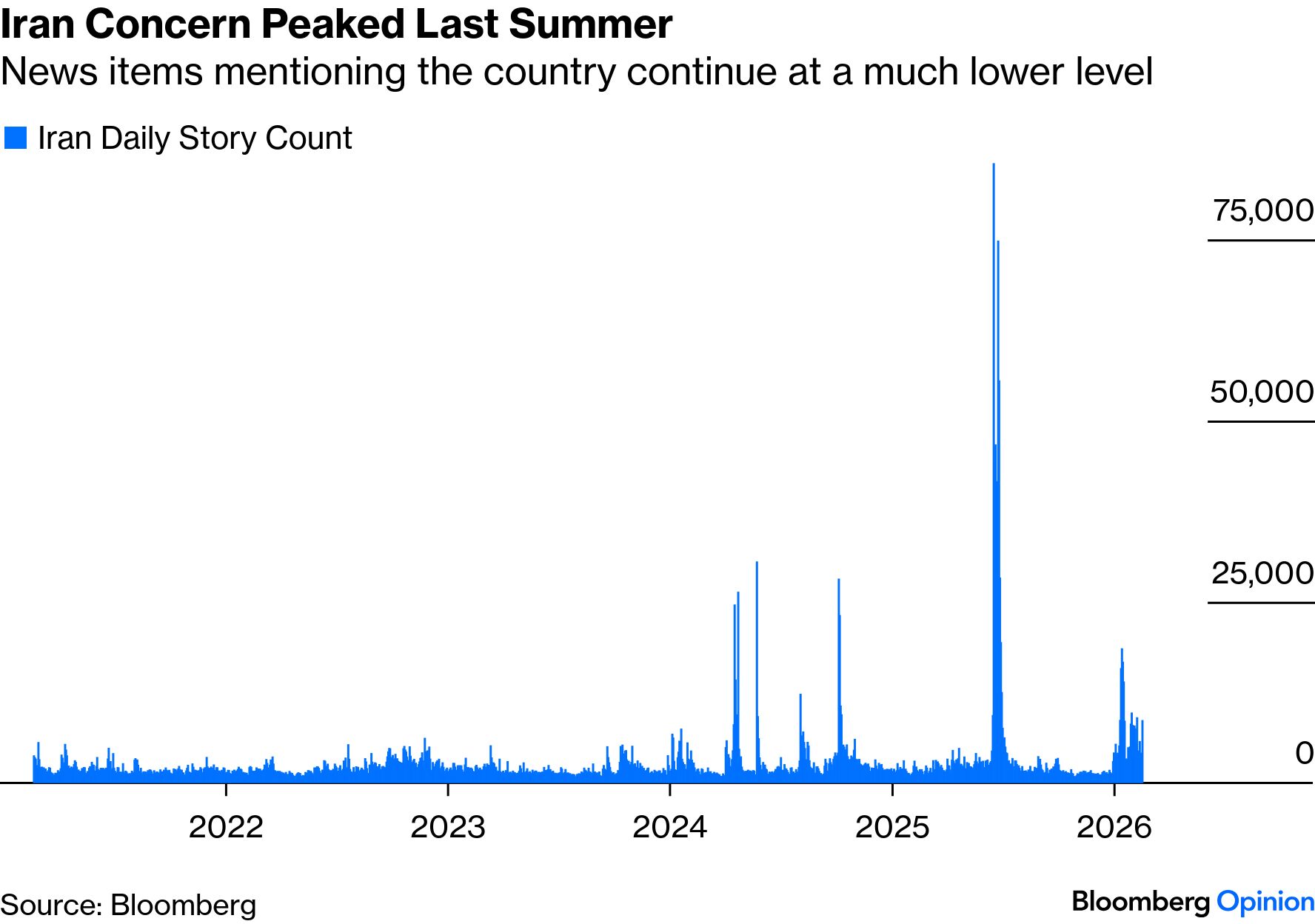

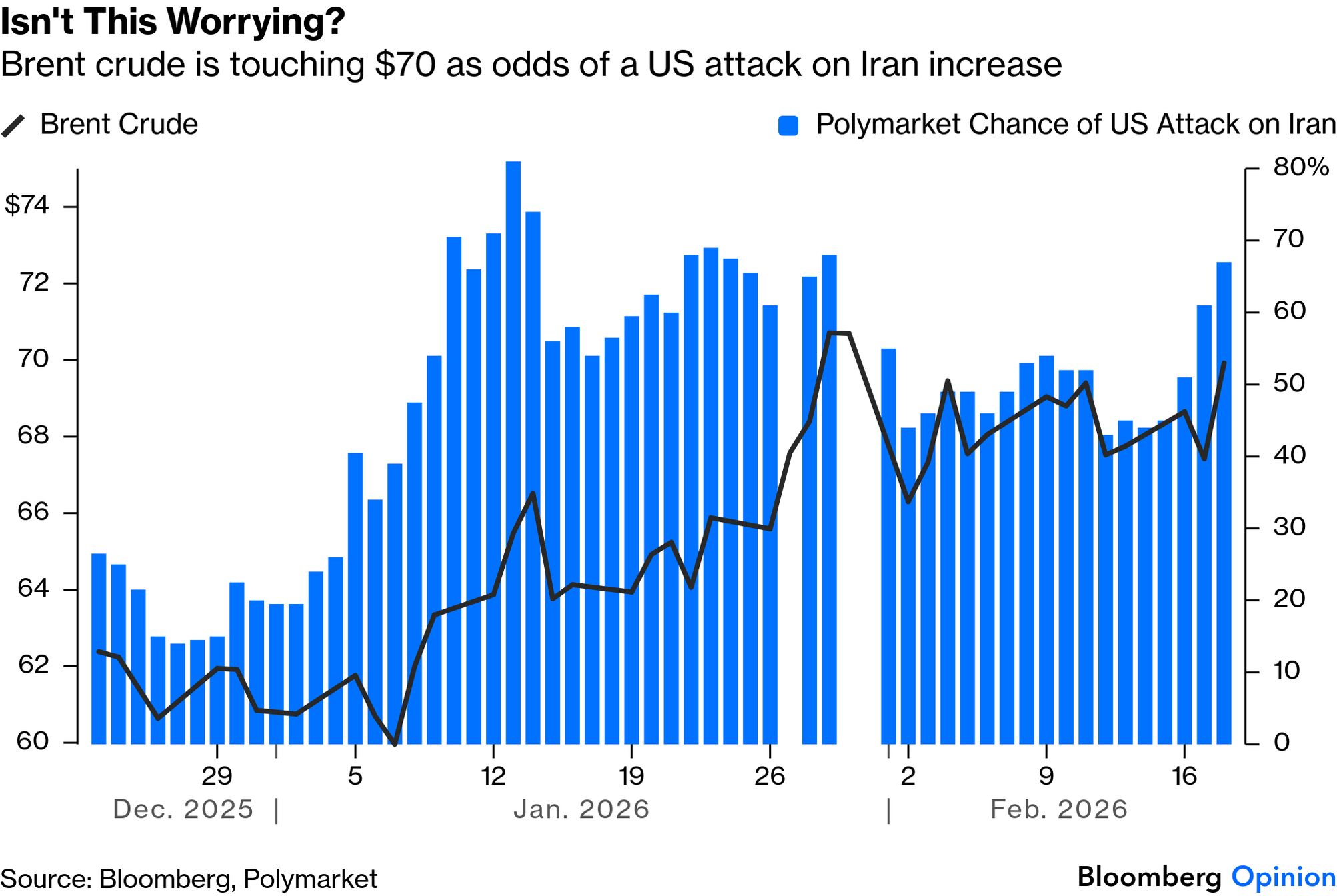

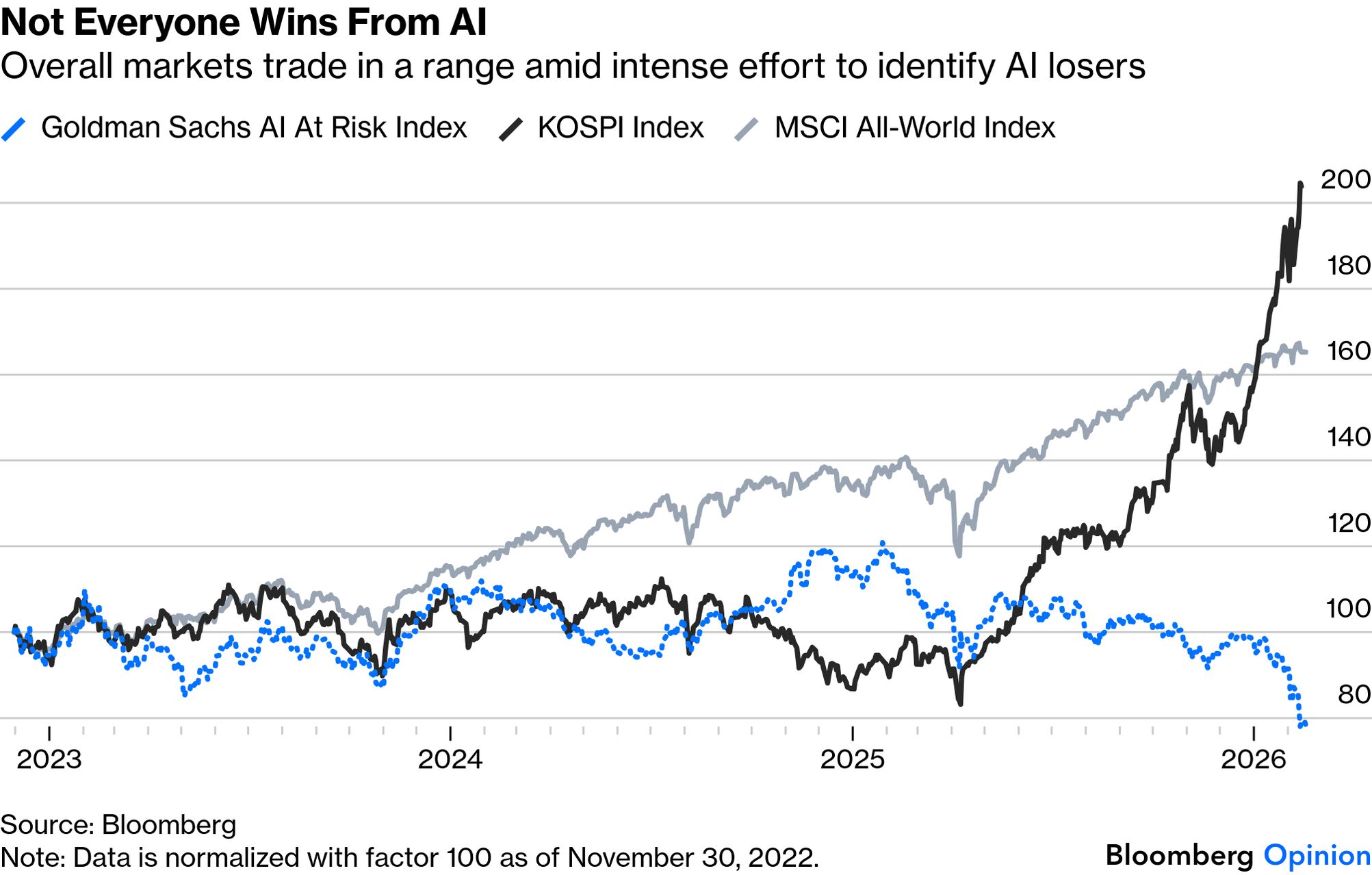

| This is a crammed news schedule. Often it's best not to try to react to every twist and turn of an emerging story, particularly if it concerns an extreme but low-probability risk. That said, there continues to be something very strange about the ongoing calm with which the world is treating the situation in Iran. According to a Bloomberg News Trends count of all stories from all sources on the terminal, the number mentioning the country is elevated at present, but far below the high last summer when the US attacked nuclear facilities with a bunker-buster bomb. It's also down significantly from the peak of the street protests earlier this year: This grows harder to explain when the sheer grimness of the latest Iran news is taken into account. President Donald Trump says the US is "ready, willing, and able to rapidly fulfill its mission, with speed and violence, if necessary." In response, Iran says it will "defend itself and respond like never before." These are just words, but the Iranian government plainly does have its back against the wall and may be getting desperate, while the US military buildup in the region is immense. Prediction market bettors now put the odds of a US attack at around 70%, while crude oil prices are rising. Brent surged 4.3% on Wednesday to top $70 once more: US Vice President JD Vance said of this week's latest round of talks on Iran's nuclear program: "In some ways it went well." But he added that Iranian representatives were still unwilling to acknowledge red lines that had been set for them, and so the possibility of conflict in a matter of weeks remains very much open. In anything like normal times, the US-Iranian saga would have dominated the news bulletins since the turn of the year, and markets would turn on it. The country's ability to administer a major oil supply shock, and its willingness to do so if attacked, are not in doubt — even if the long-term consequences of a new regime might well be very positive. As it is, the situation is only having a clear effect on oil (where supply is plentiful and prices start from a low base) and among prediction market bettors. In some ways, it's positive that broader markets feel able to ignore Middle Eastern brinkmanship. But this does intensify the risk of a major financial accident if worse comes to worst on the ground. Reality Check or Hallucinations? | If there's one question that has put US stocks through a bizarre start to 2026, it's this: "Who wins and who loses from AI?" The possibilities of artificial intelligence have driven markets since ChatGPT launched on the scene in November 2022, but careful consideration of whether the immense sums being spent will ever pay off, and who will lose out if they do, has only come recently. This chart shows the performance of Goldman Sachs' "AI At Risk" index of companies it fears stands to lose, and that of the Korean KOSPI, starting on ChatGPT's launch date: Not all those committing billions to AI infrastructure will reap returns. That holds true even for the Magnificent Seven, until now treated as inevitable AI winners. Now, as Barclays' Alex Altmann points out, they have derated back to much the same multiple as the rest of the market, thanks to concerns about their huge expenditures and the continuing opacity of their hopes to make a return on the investment. The needle may have moved too far: The near-term path of the hyperscalers and the AI narrative attached to them is the most-debated topic by investors at present given they are still delivering best-in-class earnings growth and now the least crowded versus the market in over 15 years.

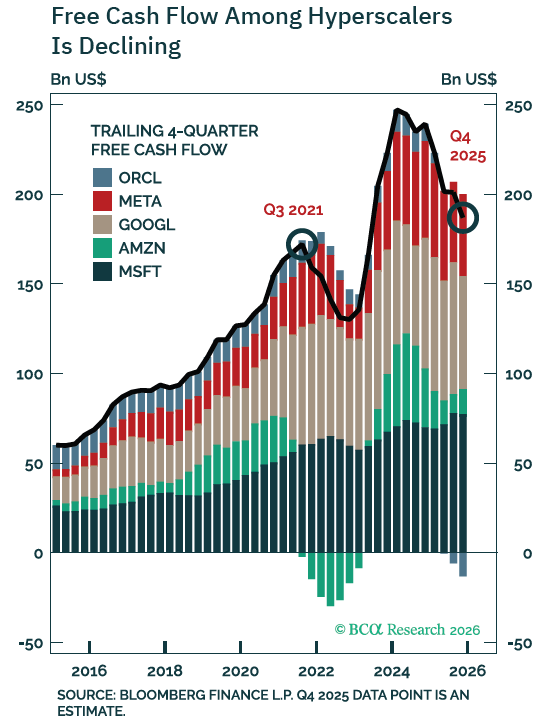

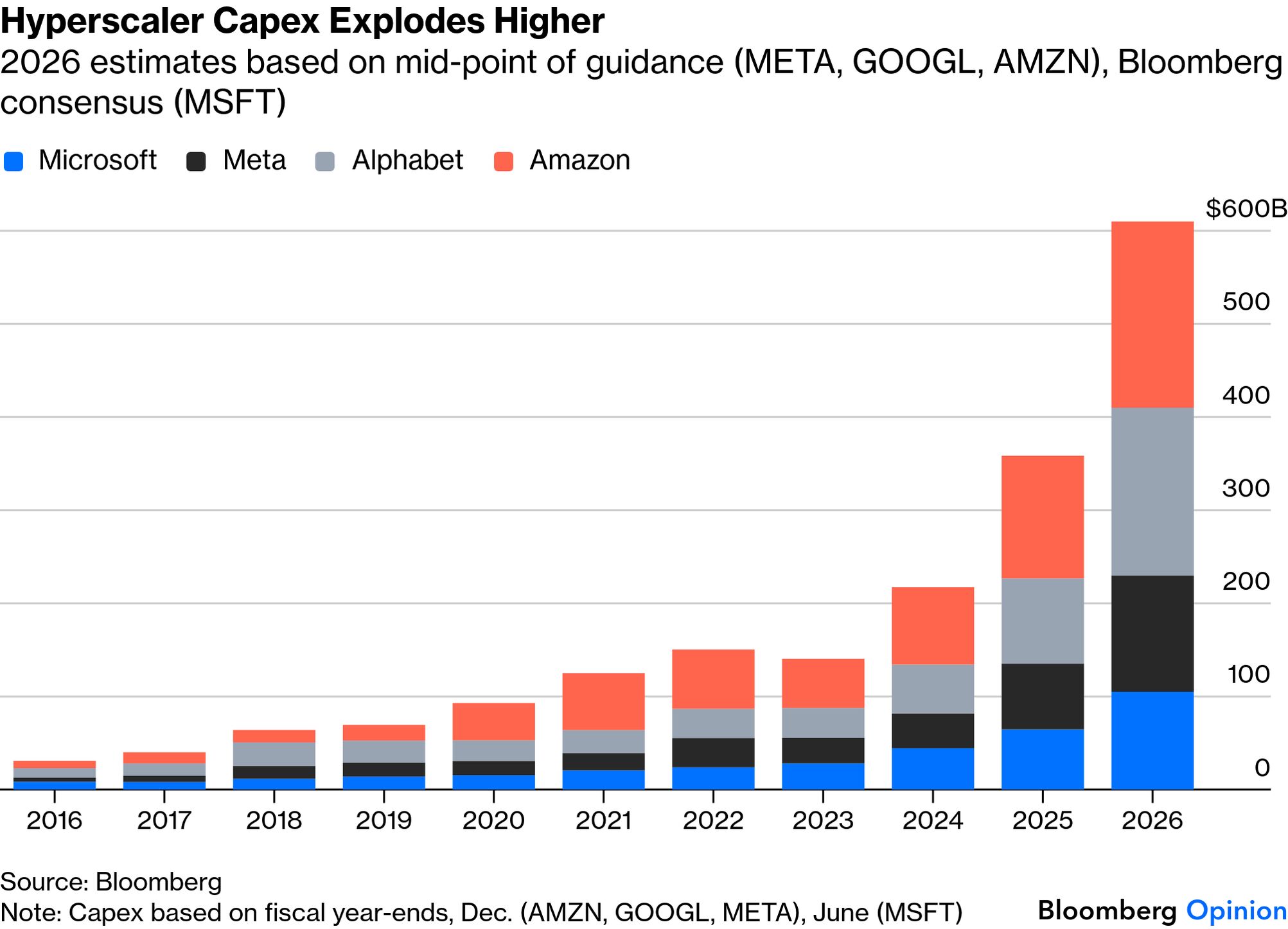

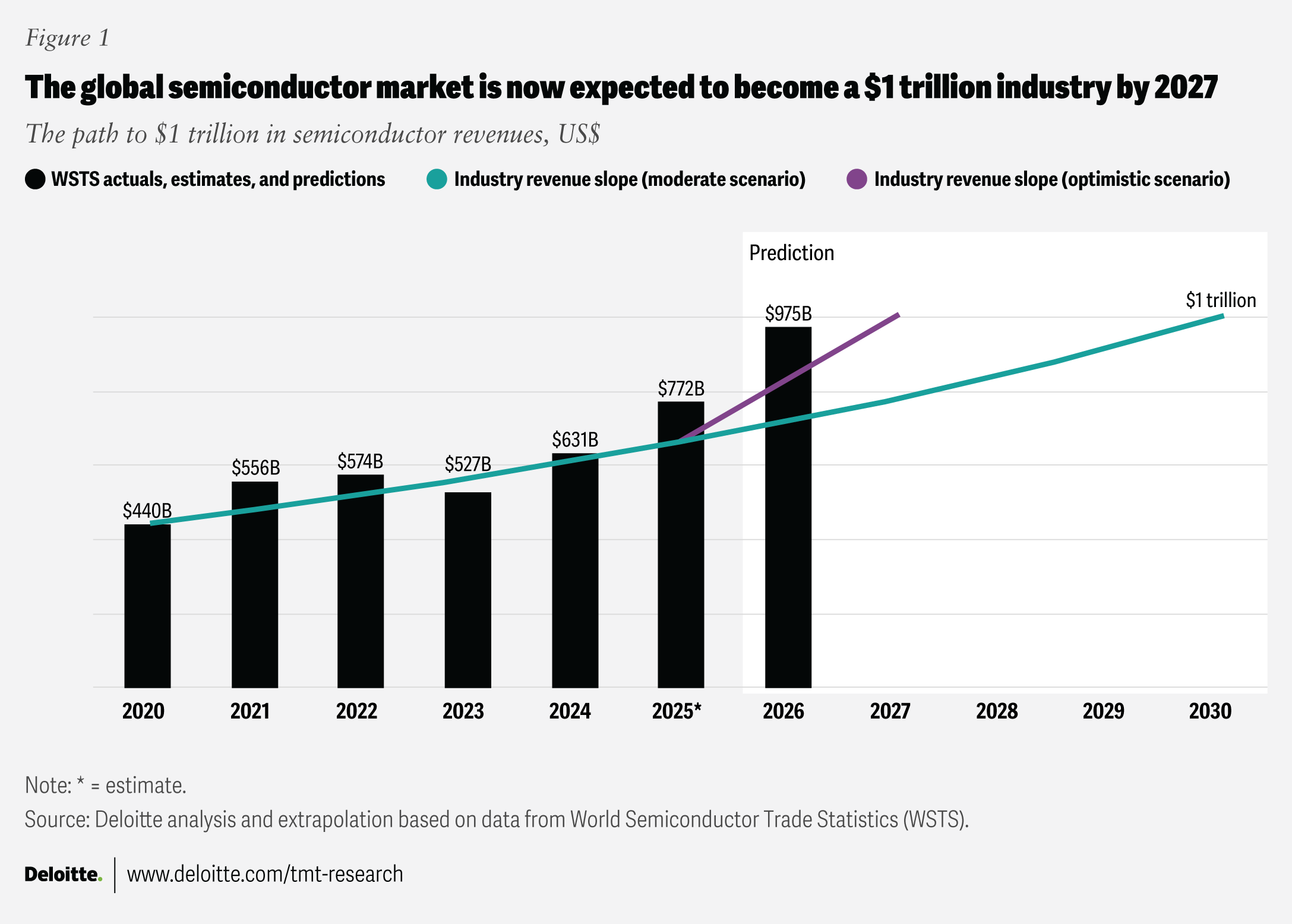

Spending such large sums carries risks, evidently. The hyperscalers have long been "capital-light," an advantage over old-line industrial companies; that is no longer the case. Also, as this chart from BCA Research shows, a direct consequence is to leave them with less free cash flow. BCA Research's Peter Berezin points out that free cash flow still exceeds capex for most of the hyperscalers, so they don't have to rely on external financing. But it understandably stirs a a perception of overinvestment, as noted by the majority of money managers in the most recent Bank of America fund managers survey. These concerns may miss a crucial point — that this capex is necessary because current infrastructure is inadequate to carry all the hoped-for advances. A recent Bloomberg Intelligence report found that only 35% of global cloud computing infrastructure is optimized for AI workloads. That suggests hyperscalers' increasing capex is justified if they want to be able to turn a profit: BI projects that the shift from central processing units (CPUs) to graphics processing units (GPUs) could help expand the market for advanced chips to about $600 billion by 2033, from $116 billion in 2024. Other estimates suggest this is conservative. Deloitte projects that AI chip sales will top $1 trillion by 2030: Predictions like this explain why hyperscalers don't want to take their foot off the gas. But still, Meta Platforms' recent earnings underscore a key reality — investors are more willing to tolerate costly buildouts when companies can prove that earlier spending is already feeding through to profits. How do companies that still need to make substantial investment avoid investors' wrath? Berezin argues they may ultimately scale back their spending to appease shareholders. That would bring the AI capex narrative close to breaking point — but such a pragmatic response wouldn't deal with the fundamental problem that the current computing infrastructure is inherently constrained. Alpine Macro's Noah Ramos cites recent earnings from Microsoft and Amazon to show that tech groups should stay the course. Both demonstrated that they badly needed the extra capacity the capex would buy for them. Microsoft said that over 40% of its cloud business was going to OpenAI, which the market hated due to concentration risk, while Amazon's cloud business has a backlog, forcing it to turn away business: For a hyperscaler to not build out the infrastructure, they're deferring revenue further and won't be able to capture it. The risk of not building out in the short term due to having a market pullback does not outweigh the long run.

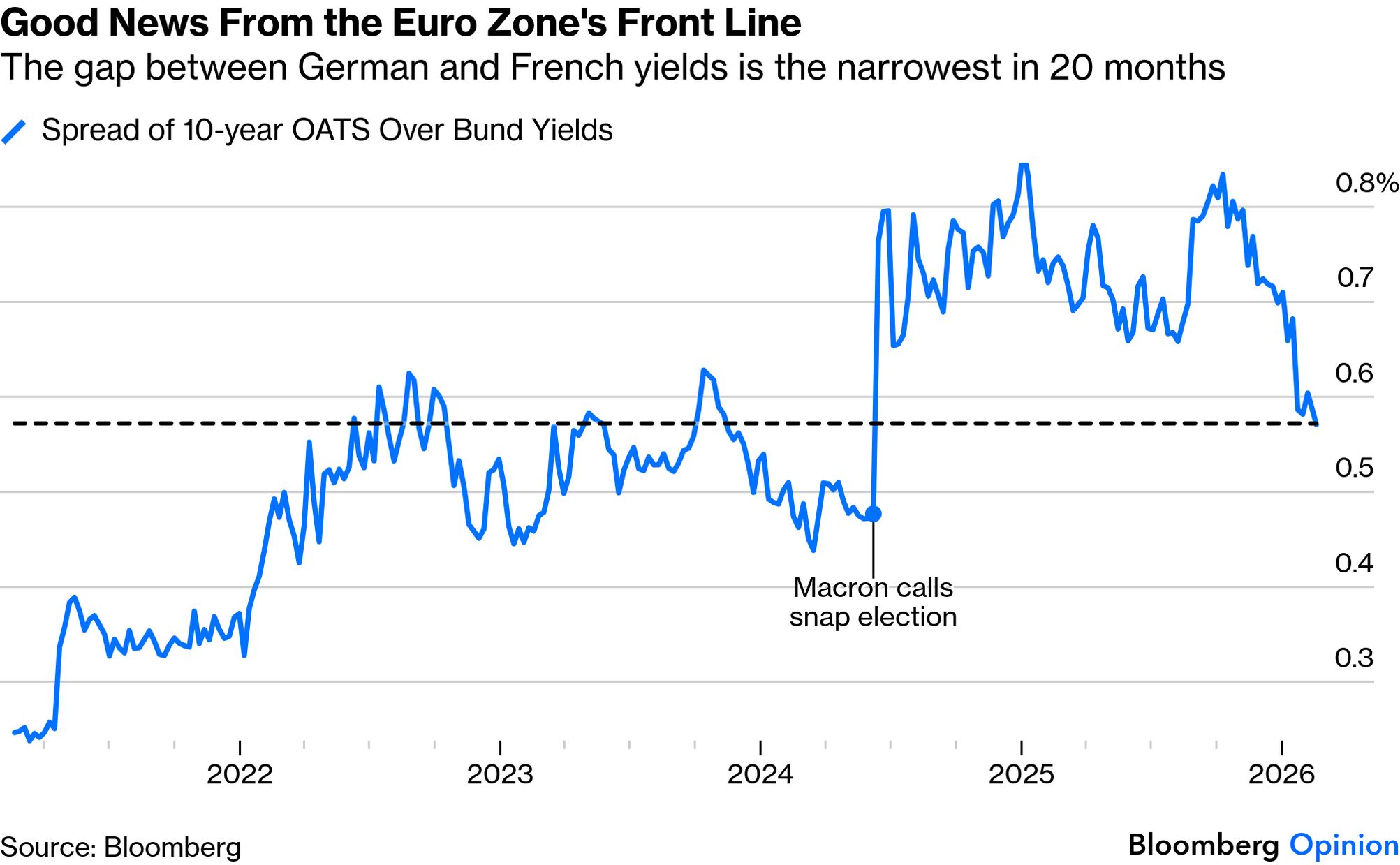

In other words, short-term concerns might drive a long-term mistake. To quote Shaia Hosseinzadeh of OnyxPoint Global Management, "This industrial revolution is unfolding in five years instead of 50. And we are trying to value it on a quarterly earnings model. No one alive has firsthand experience investing through a shift of this speed or magnitude." Hosseinzadeh notes further that Wall Street's habit of applying linear models to non-linear change is fault-prone and risks systematic over- or underestimates. After all, nobody predicted Amazon's hyperbolic growth after the dot-com bust. Wall Street's new emphasis on both the costs and benefits of AI, rather than just the benefits, is a healthy development. But it shouldn't be taken too far. —Richard Abbey More Central Bank Politics | Before Washington could even bring the saga of replacing Jerome Powell at the Federal Reserve to a conclusion, a similar drama is starting in Frankfurt. Christine Lagarde, according to the Financial Times, is planning to step down before the official end of her term in October 2027. The report hasn't been confirmed, but rings true as it would ensure that the existing French president, Emmanuel Macron, has a role in choosing her successor. By next May, there's a real possibility that France will have elected a hard-right leader. Like Powell's, her legacy will divide opinion for years to come. But Lagarde stands to leave with the European financial project looking its healthiest in years. Crucially, the market is beginning to relax over the fiscal crisis in France, which caused the yields of French OATS to explode after Macron's disastrous snap election in 2024 left the country with a logjammed legislature. The spread of OATS yields over equivalent German bunds, a terrifying source of friction at the heart of the euro zone, has in recent weeks regained most of the ground lost during Paris' political crisis: The recent weak dollar has also boosted the euro's buying power. In real effective terms, taking account of inflation, the currency is its strongest in more than a decade, at the top of its range since Greece's fiscal woes plunged the continent into a sovereign debt crisis in 2010: If these developments show the positives of the European project, the accelerated process of finding Lagarde's successor could parade the negatives. On top of arguments between hawks and doves, there is an arm-wrestle for national advantage as different countries try to get their person in place. Germany provides the ECB's Frankfurt home, but in a quid pro quo no German has ever headed it. Europe's biggest economy, with a tradition of tight money and a recent history of enforcing austerity during the sovereign debt crisis that infuriated the continent's periphery, retains great influence over the outcome. As a German, Ursula von der Leyen, currently heads the European Commission, the country is highly unlikely to provide the next president. The hawkish German governor Isabel Schnabel told Bloomberg that she would see out her term, which ends at the same time as Lagarde's. Spain, the most successful euro zone economy of late, is campaigning for its own candidate. Klaas Knot of the Netherlands seems the most likely contender on whom all could agree Once an ECB leadership is in place, the bank is more capable of swift and decisive action than any other European institution, as it has shown in successive crises. The selection process threatens to display why Europe's other institutions never get their act together. |

No comments:

Post a Comment