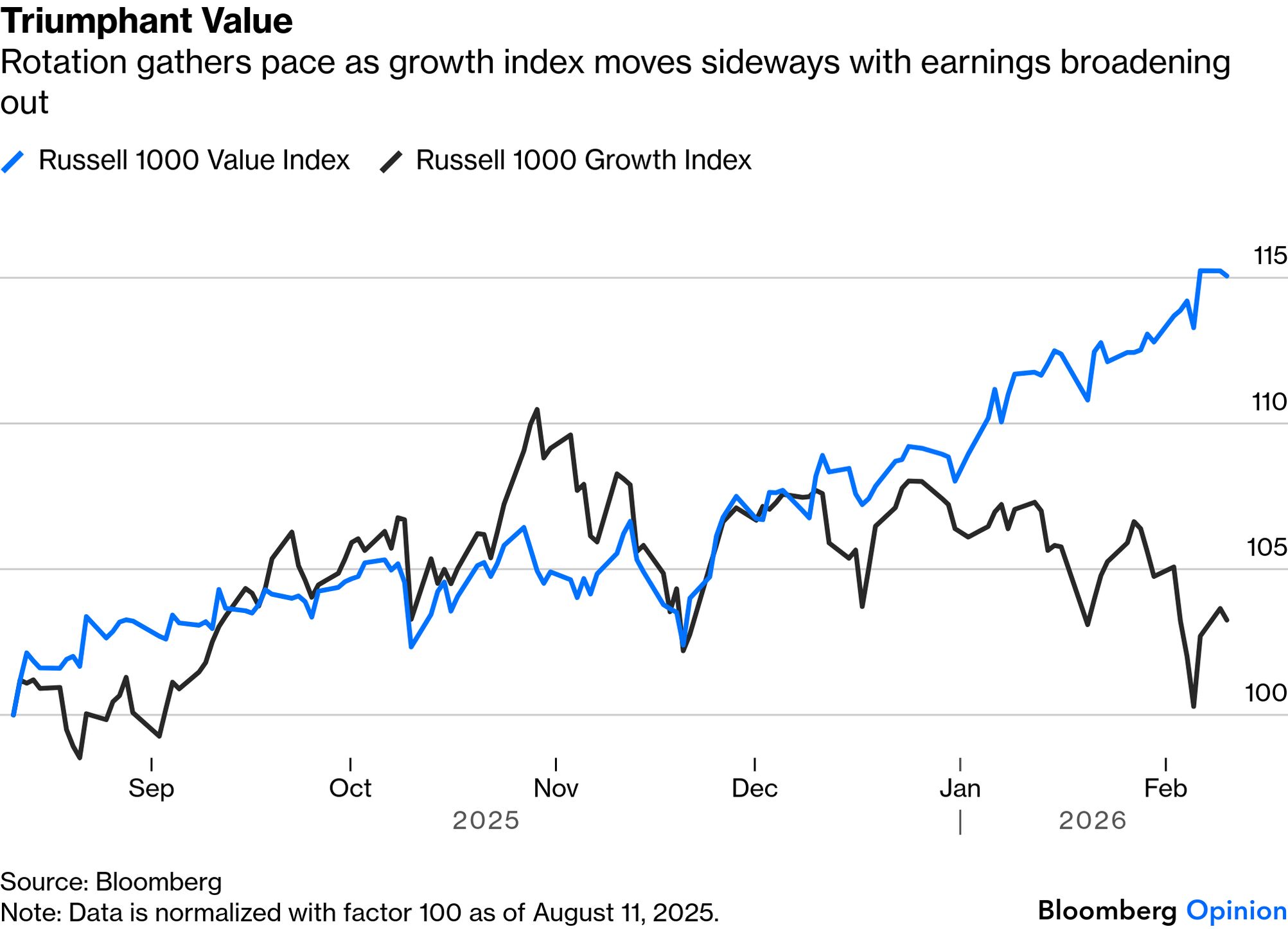

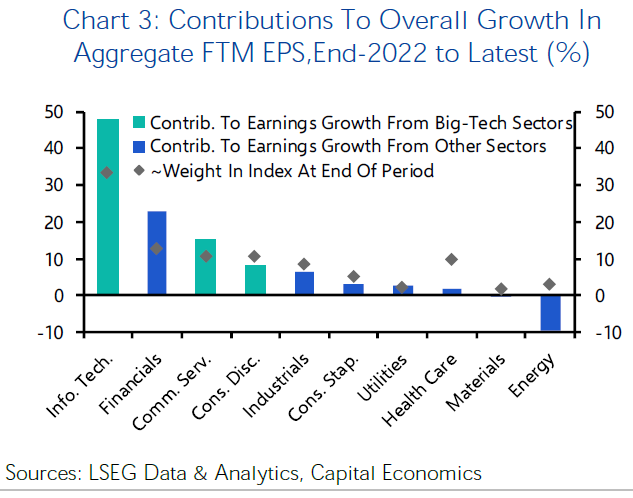

| As the fourth-quarter earnings season comes to an end, the evidence of a full-blown rotation is unmissable. Extreme concentration had created this; the top 10 US stocks make up 39% of the S&P 500 compared to 26% at the peak of the dot-com bubble. The market seemed overdue for a broadening out. That's happened in the last few weeks. One way to gauge the scale of the rotation is through the Russell 1000 Value Index, which has opened a big lead over the equivalent Growth Index since mid-December: But market concentration isn't primarily about share-price valuations; rather, it's been driven by unbalanced earnings growth. Since the end of 2022, the largest 10 companies in the S&P 500 have accounted for about two-thirds of the index's overall EPS growth. During the dot-com bubble, they accounted for around one-quarter, according to Capital Economics. The tech sector's dominance has been total: Barring a profound change in the US economy, such clustered profits cannot continue. For the rotation to be sustained, they need to widen. Bankim Chadha of Deutsche Bank AG notes that this season growth has extended beyond the mega-cap tech companies: Overall earnings growth nudged higher to a 4-year high (14.5%), and the number of sectors with positive growth rose again to 8 out of 11, up from 6 in Q3. Nearly half the companies grew at double-digit rates, with the median growth rate close to 10%, also the highest in 4 years.

ClearBridge's Jeffrey Schulze and Josh Jamner show that earnings correlate with economic cycles — and according to their model, we are currently in a "solid overall expansion," which bodes well for profits. This is borne out by the 75% of S&P 500 members that have reported so far. Cyclical tailwinds such as tax refunds under the One Big Beautiful Bill should ensure that this continues for a while. Atop this cyclical narrative is the AI story, which Societe Generale SA's Andrew Lapthorne argues may, ironically, prove most disruptive for the less capital-intensive industries that have traded at higher multiples. Now, firms prized for their capital-light models are being compelled to spend aggressively just to avoid falling behind: Last week saw a major rotation into what we'd call AI‑immune sectors, such as Utilities, Food, Mining, Construction, Telecoms, and a whole host of other sectors not obviously replaced by the likes of Claude. This rotation from the "new" to the "old" economy is very reminiscent of the 2000–2003 growth‑to‑value period.

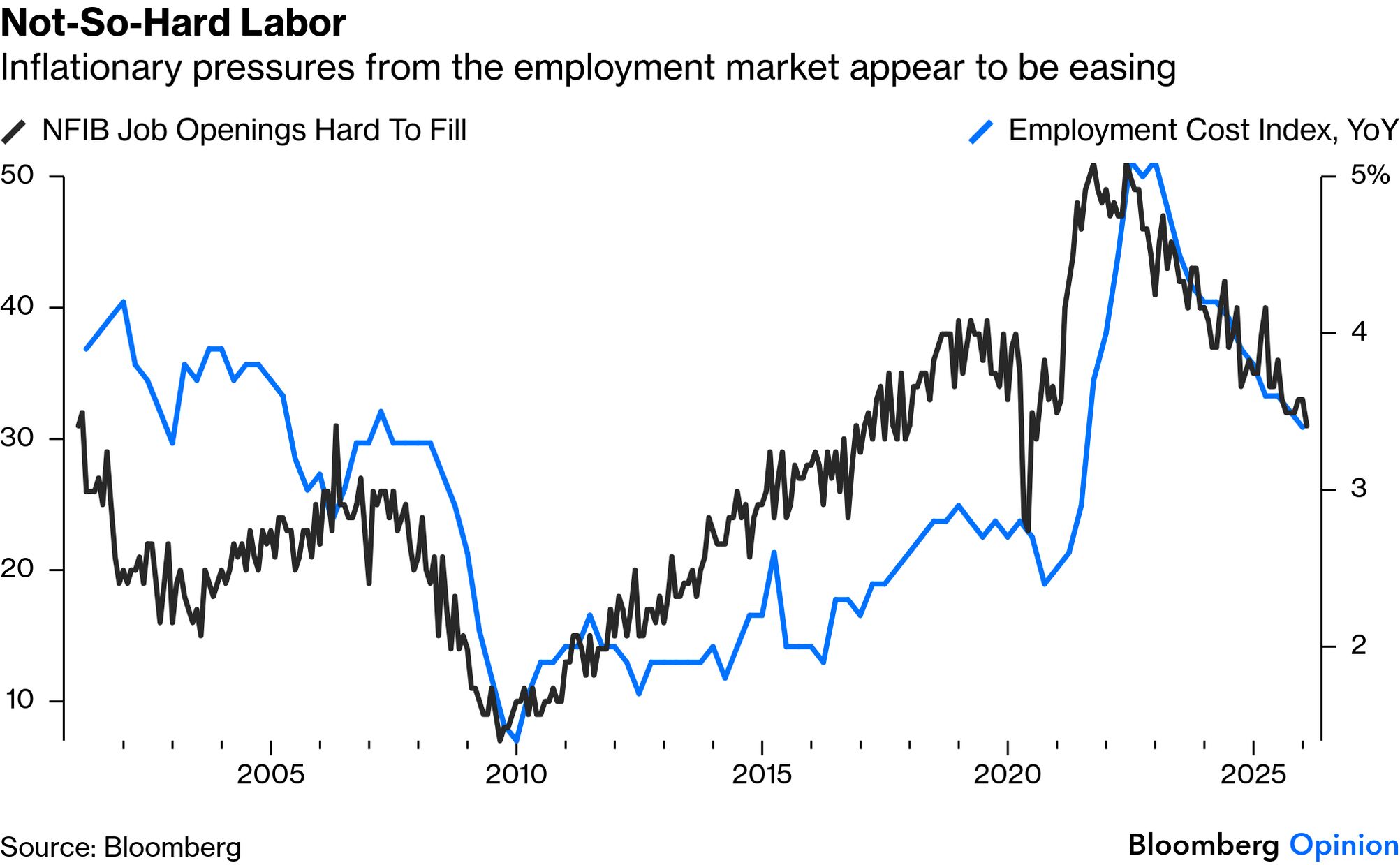

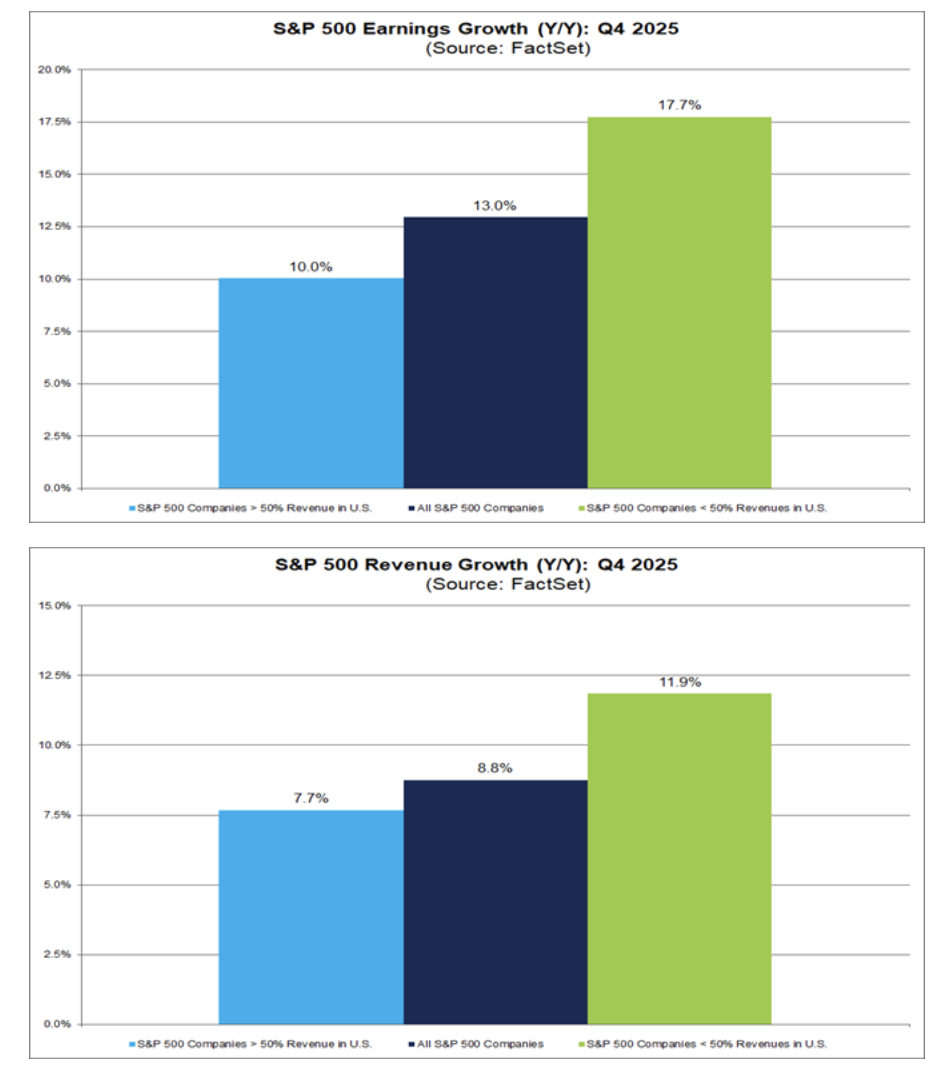

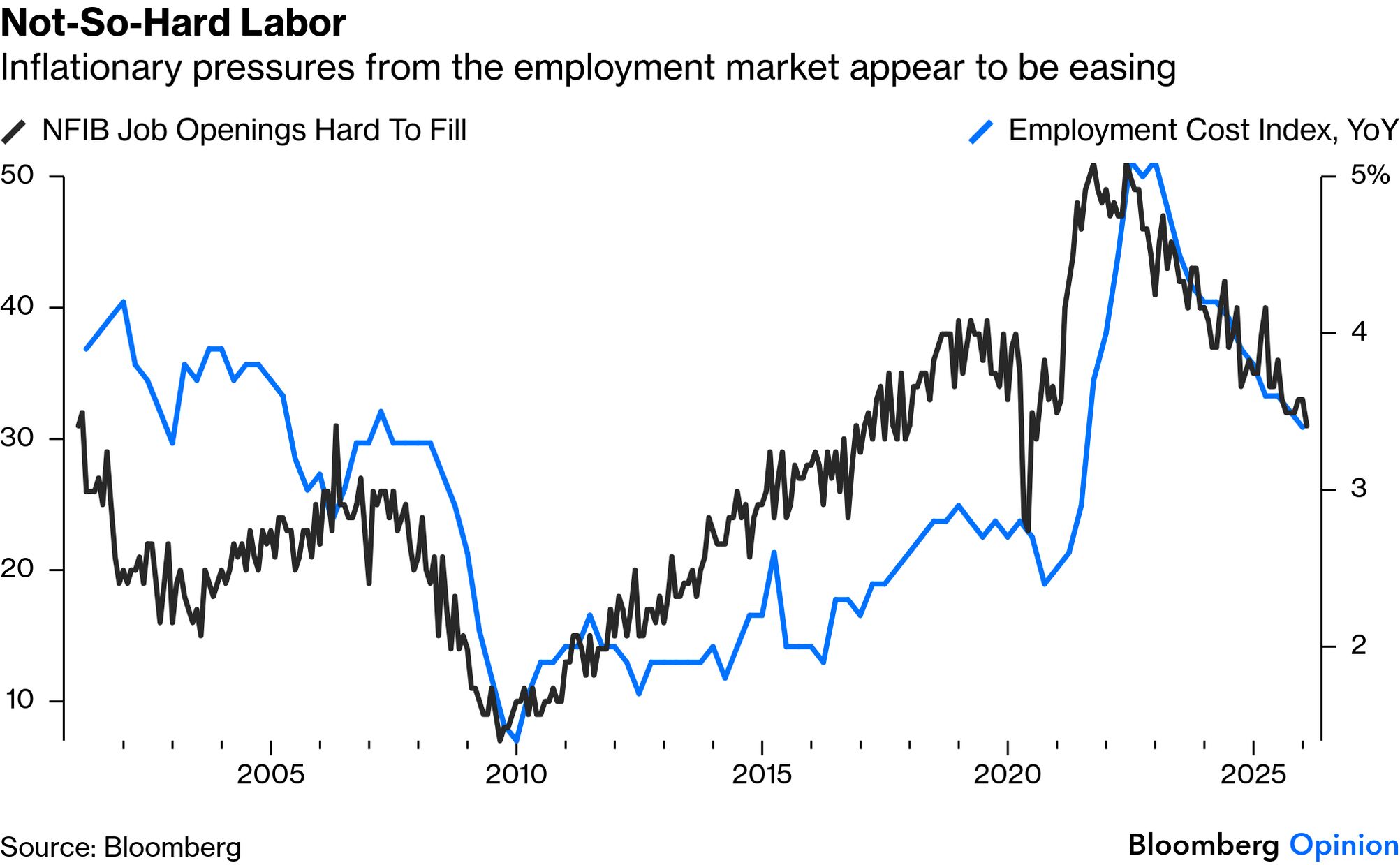

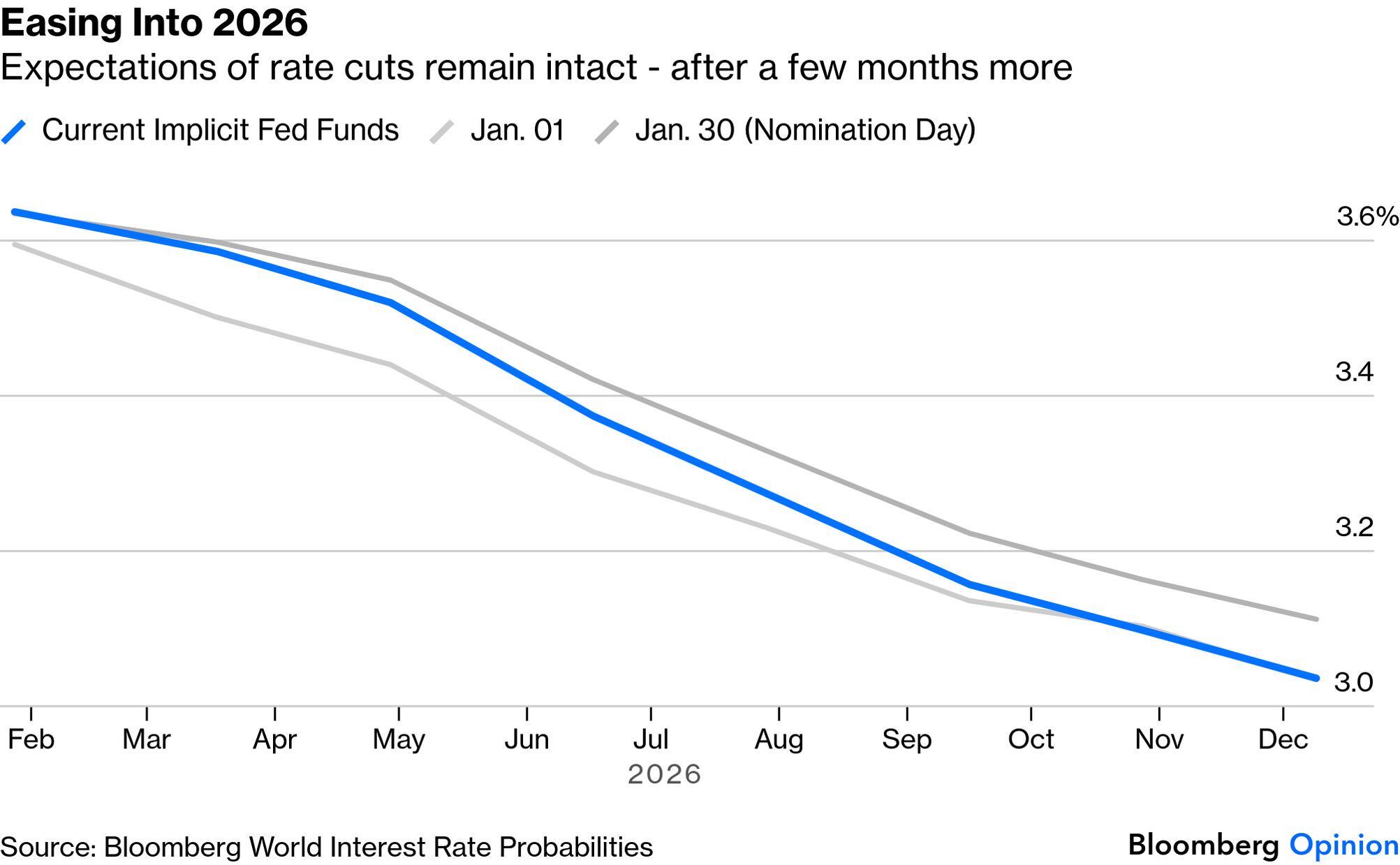

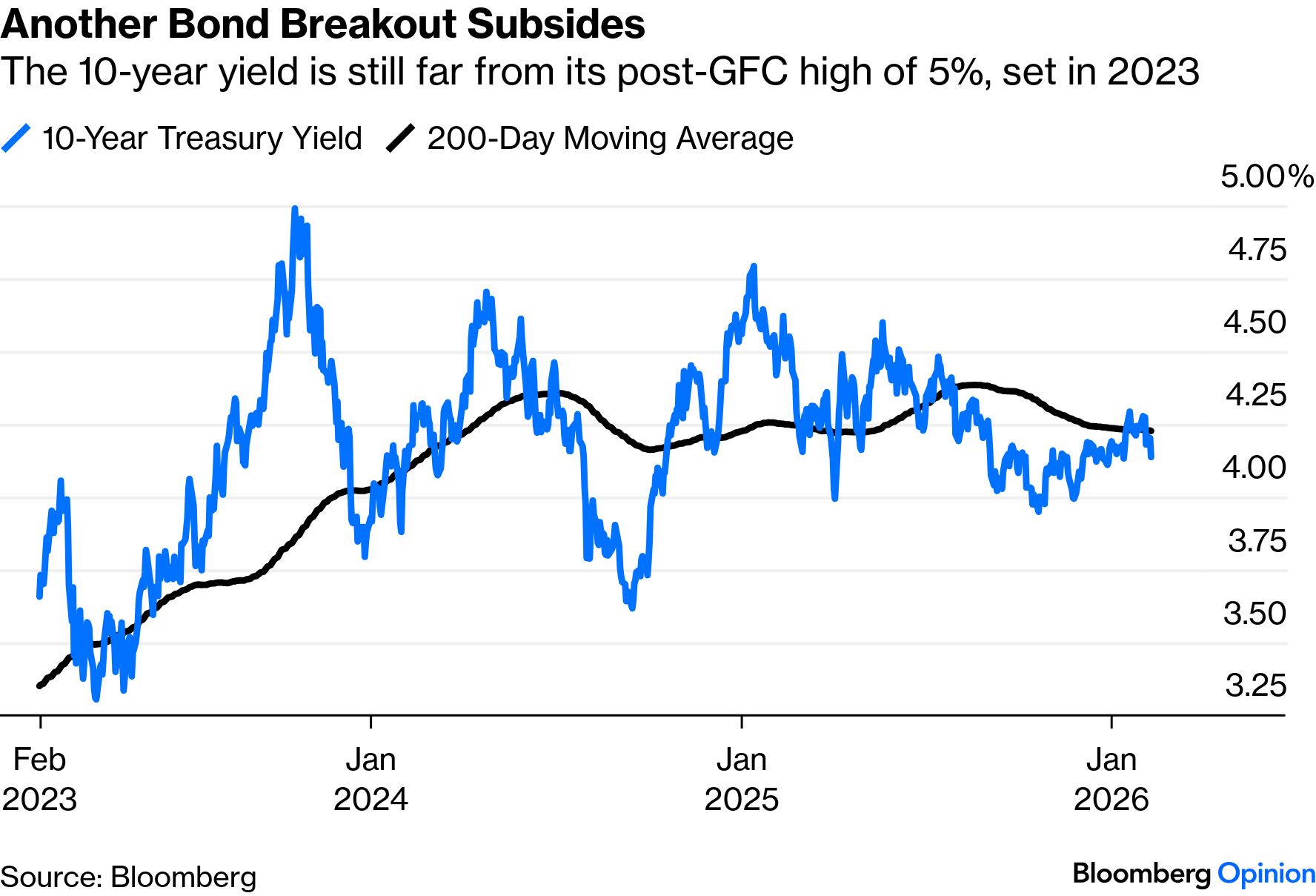

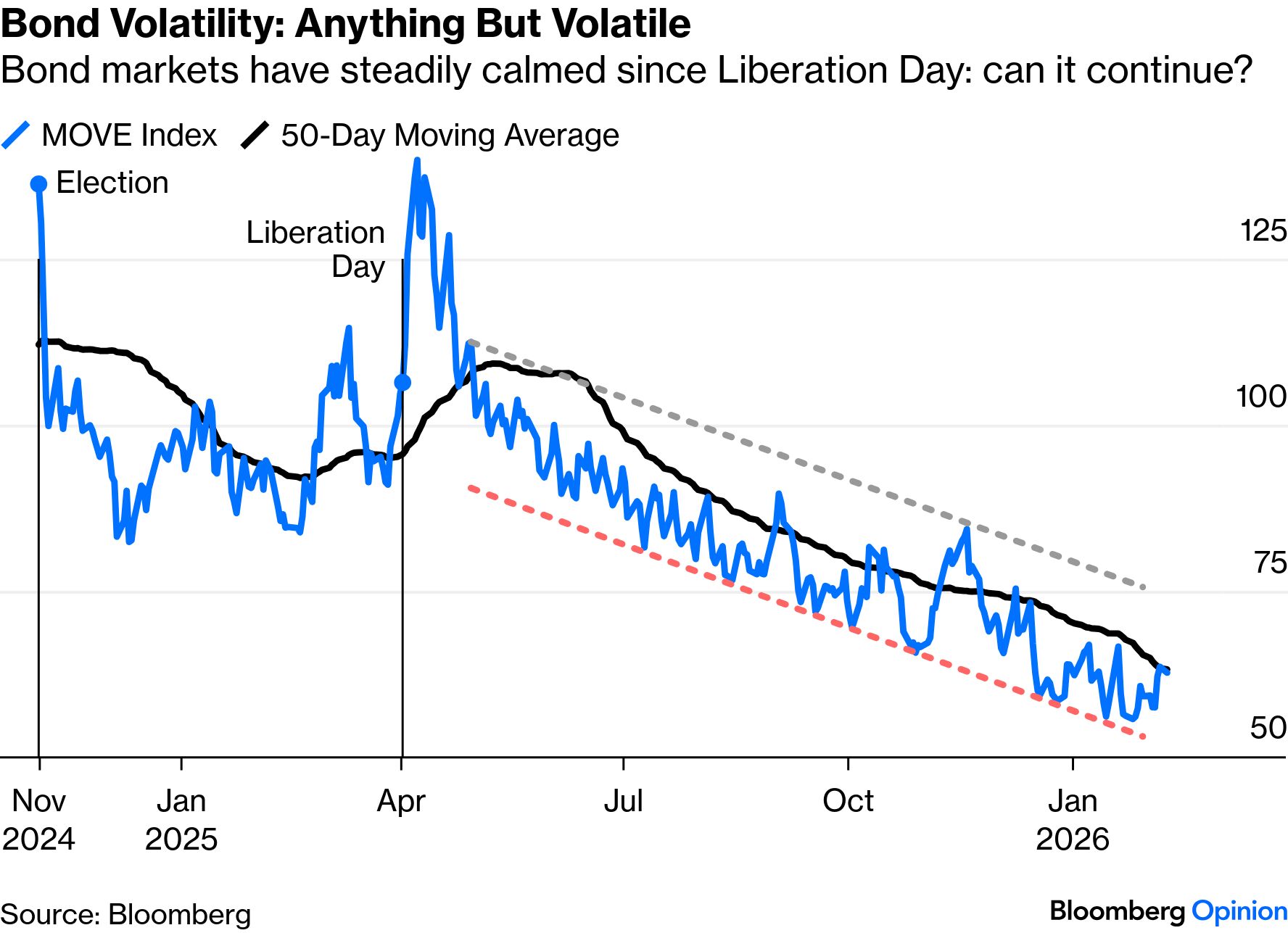

Meanwhile, the weak dollar also had an impact. John Butters of FactSet points out that S&P 500 exporters that gain most of their revenue outside the US are reporting higher earnings and revenue growth: Butters explains that this is largely because of Nvidia Corp., which reports later this month. It's the single largest contributor to both earnings and revenue growth among S&P 500 firms with predominantly international exposure. Strip it out, and blended earnings growth would fall to 12.0% from 17.7%, while revenue growth would slow to 9.9% from 11.9%. Capital Economics' Thomas Mathews argues that the rally depends "quite heavily on the business models of a small handful of companies." In these circumstances, idiosyncratic developments at one or more of them, or "perceived missteps in the AI race," could drag on the whole market. But greater dispersion among the mega-caps in the last few months hasn't taken the overall market far down from all-time highs. And the rotation is driven less by problems for the behemoths than by the cyclical factors that have improved earnings for everyone else. -- Richard Abbey An extremely unusual Non-Farm Payrolls Wednesday is in prospect, after the brief shutdown forced the postponement of last Friday's unemployment data. It appears that the heat is continuing to ebb (taking with it the justification for tighter money). The National Federation of Independent Business' monthly survey of small company managers found the proportion finding job openings hard to fill dropped to its lowest since the pandemic, while the quarterly employment cost index (which includes benefits and bonuses as well as salary) also continued to slow down:  In combination with surprisingly low US retail sales for December, this contributed to a shift in expectations for the Federal Reserve under its next chairman. President Donald Trump's nominee Kevin Warsh is seen as less likely than some of his competitors would have been to pursue rate cuts at all costs. The Jan. 30 announcement saw the implicit fed funds rate for the rest of this year drift upward. That has now moved back — with data like this, traders expect the Warsh Fed will need to cut twice this year: This also helped a good day in the Treasury market, where worries that the economy could be overheating had been pushing yields up. There are still plenty of buyers for US government debt. The benchmark 10-year yield dropped six basis points on the economic news, bringing it back below its 200-day moving average. Its brief post-pandemic peak of 5% is now more than two years in the past: A key point in keeping liquidity flowing easily is the ongoing reduction in bond volatility. As measured by the MOVE index, it suggests a stunningly reliable decline ever since the shock surrounding the Liberation Day tariffs last April: This is a very strange state of affairs at a time when the market has dealt with a series of geopolitical shocks, and must also contend with fears of an investor revolt against fiscal over-stimulus. But as with equities, it may be driven by the economic cycle, which is currently at a point of expanding. Chris Watling of Longview Economics argued: "If you are in the middle of the economic cycle, why wouldn't you have low bond volatility?" He added that the MOVE index showed that fears of a fiscal crisis were not prevalent. But even if the economic and corporate profits cycles are in a healthy place, it doesn't necessarily follow that the financial liquidity cycle will continue to support them. This is the contention of Michael Howell of Global Liquidity Indexes, who suggests that Warsh's well-known intent to shrink the Fed's balance sheet could be a problem: Strong economies don't always have strong financial markets. History shows that strong economies can falter in weak markets when liquidity is withdrawn. While we question the wisdom and practicality of aggressively draining liquidity now, the direction is clear: The era of expanding US Fed liquidity injections is over.

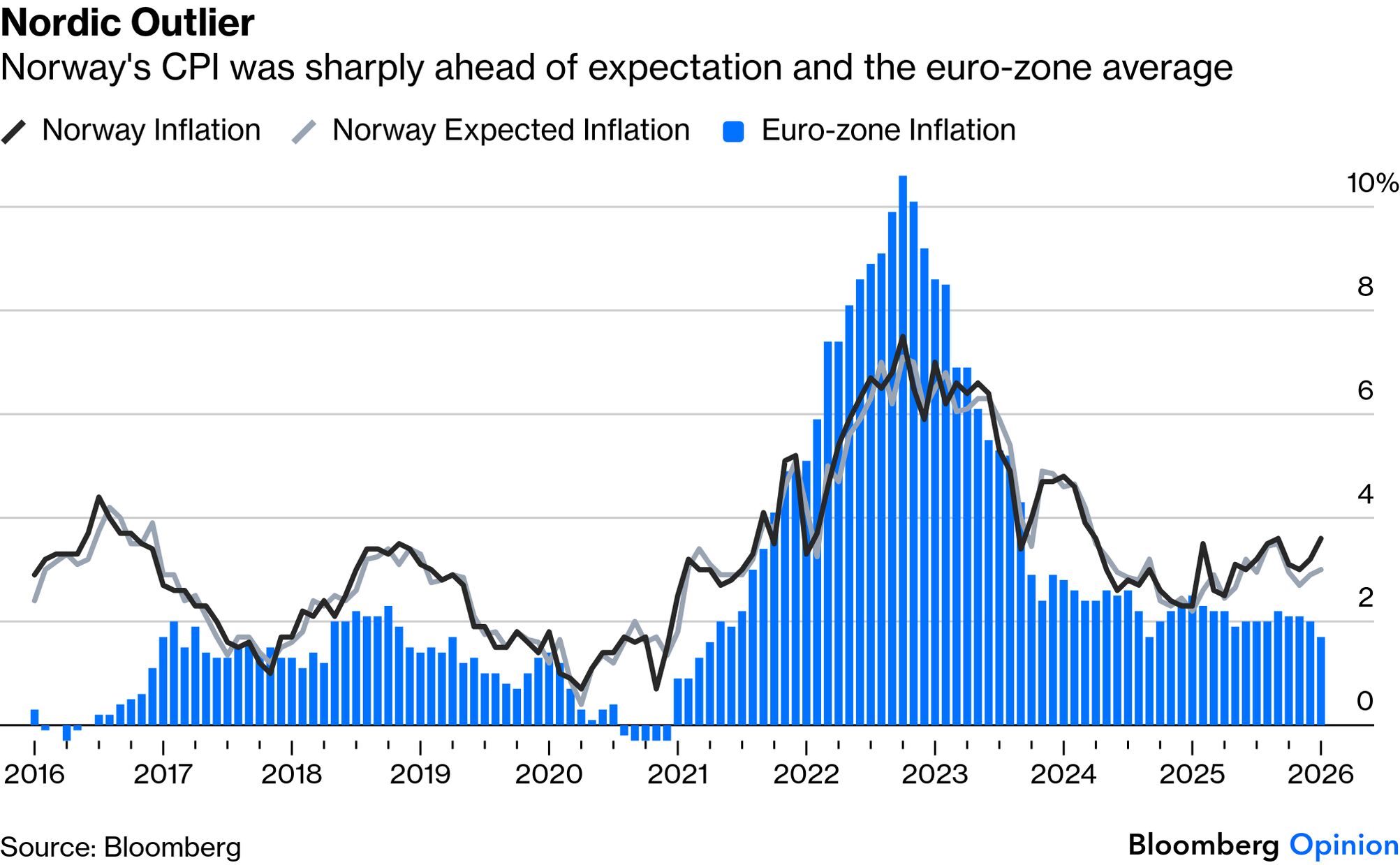

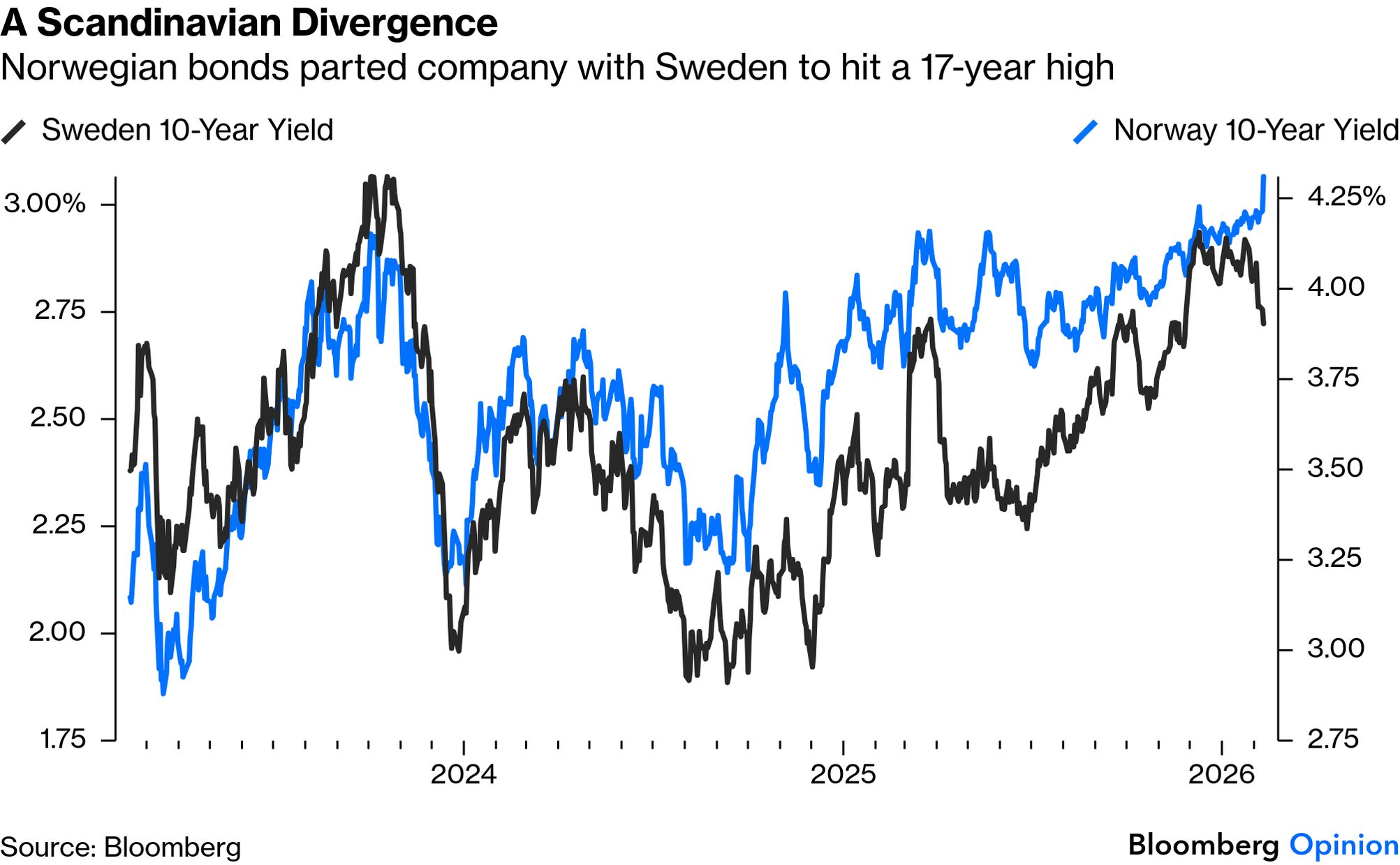

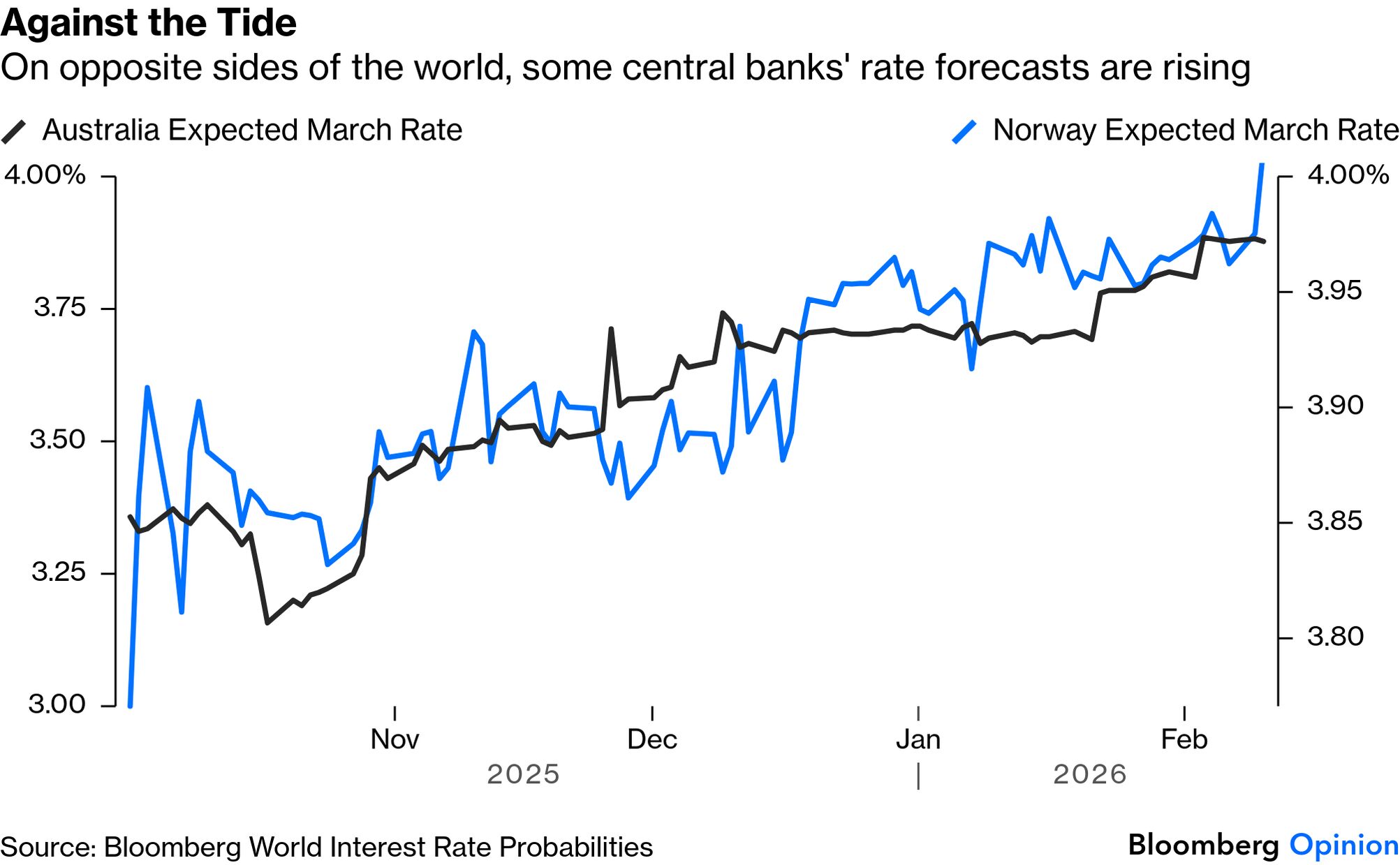

Howell argues that we are at "an inflection point, moving from a cycle phase dominated by monetary stimulus to one where liquidity is drying up." If he is right, then heightened volatility and a re-pricing of speculative assets will follow. "The free money that lifted all boats is being withdrawn. We appear to be at the early stages of a downswing. Watch the data closely." For now, however, we remain in the sweet spot. At least until we get the delayed unemployment numbers, shortly after you receive this. Norway is famous for its blue parrots (and its soccer commentators). Is it also offering a canary in the coalmine? The country's January inflation came in sharply ahead of expectation, and also far ahead of the rate of price rises in the rest of Europe: That prompted quite a market reaction, with Norwegian 10-year yields rising steeply to a level not reached since early 2009. Norway's bonds regularly trade at a higher yield than neighboring Sweden's, but the divergence between the two is now particularly stark: This has fed into speculation that the Norges Bank, like the Reserve Bank of Australia earlier this month, will be required to move against the trend for declining rates in the developed world and opt for a hike. Norway's is now expected to do so in March. In both cases, overnight index swaps show that expectations for rate cuts have whittled away steadily over the last few months: How alarming is this? Norway is a sufficiently unusual economy, with far greater reliance on energy than other European countries and a history of erratic inflation forecasts, that it needn't prefigure problems elsewhere. It undershot the euro zone's inflation during the worst of the post-pandemic price spike; it's not necessarily alarming that it's overshooting now. As yields fell across the euro zone Tuesday, that's how the market is interpreting it. But it's a reminder that different economies can diverge further as the global Covid shock disappears into the rear mirror. |

No comments:

Post a Comment