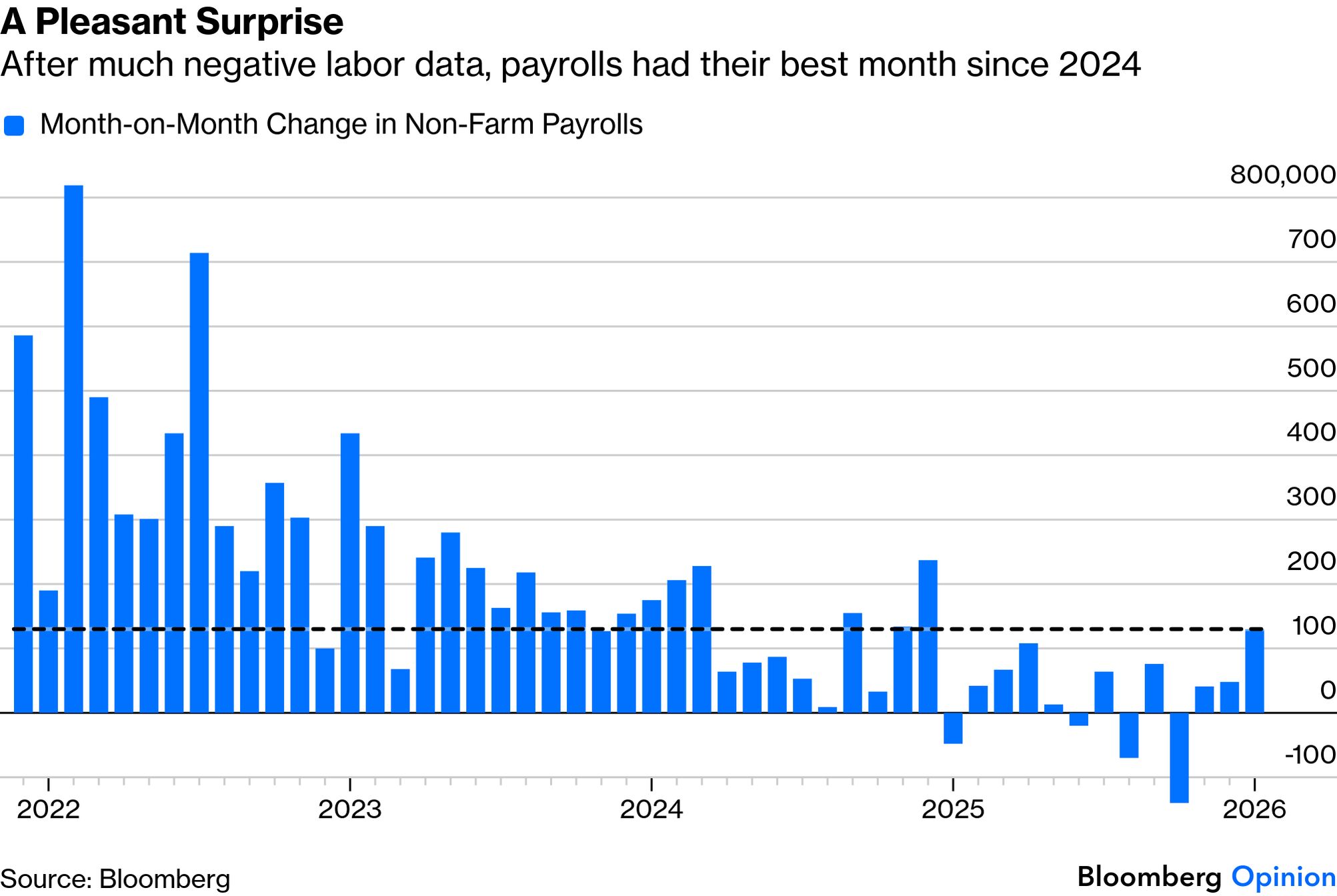

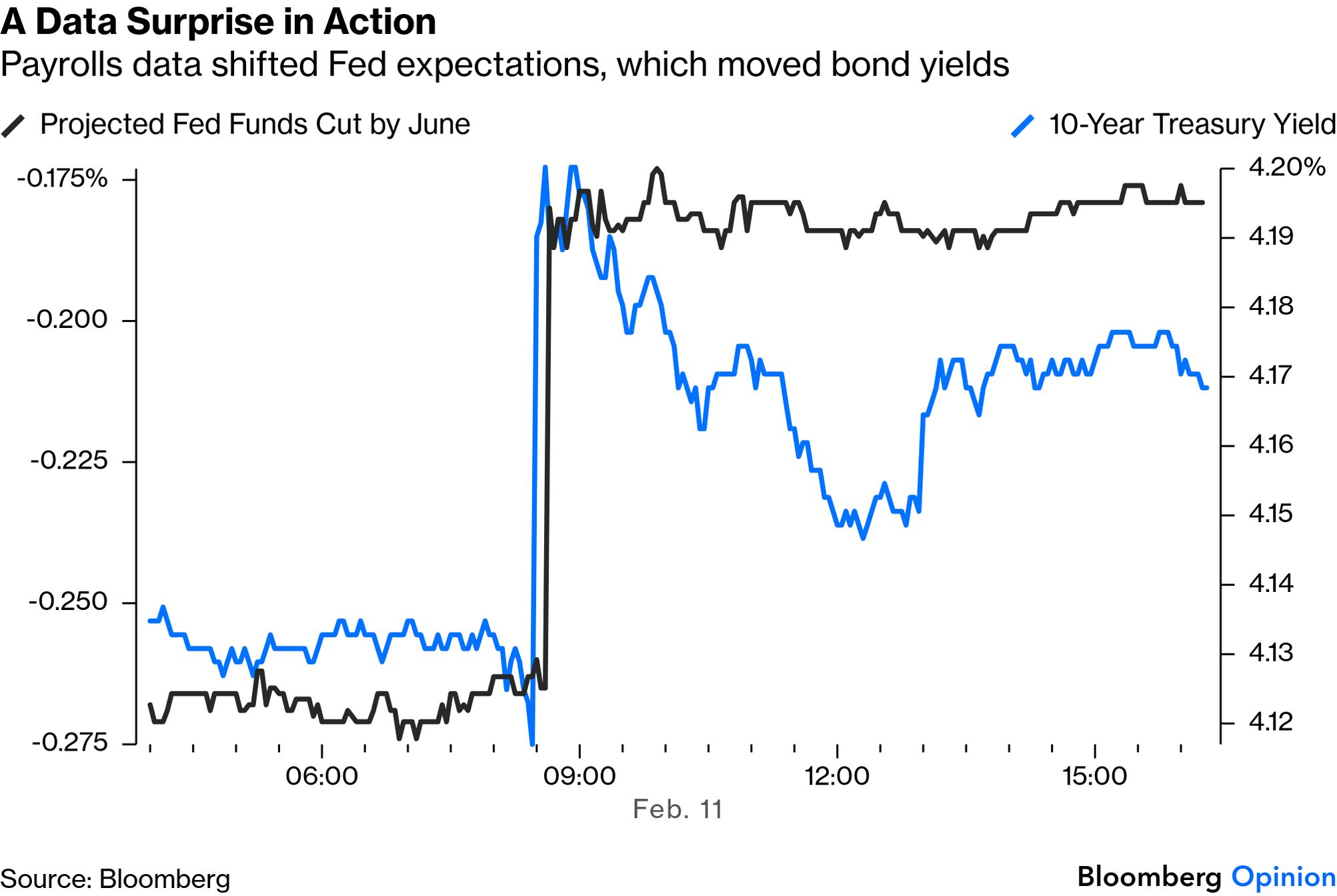

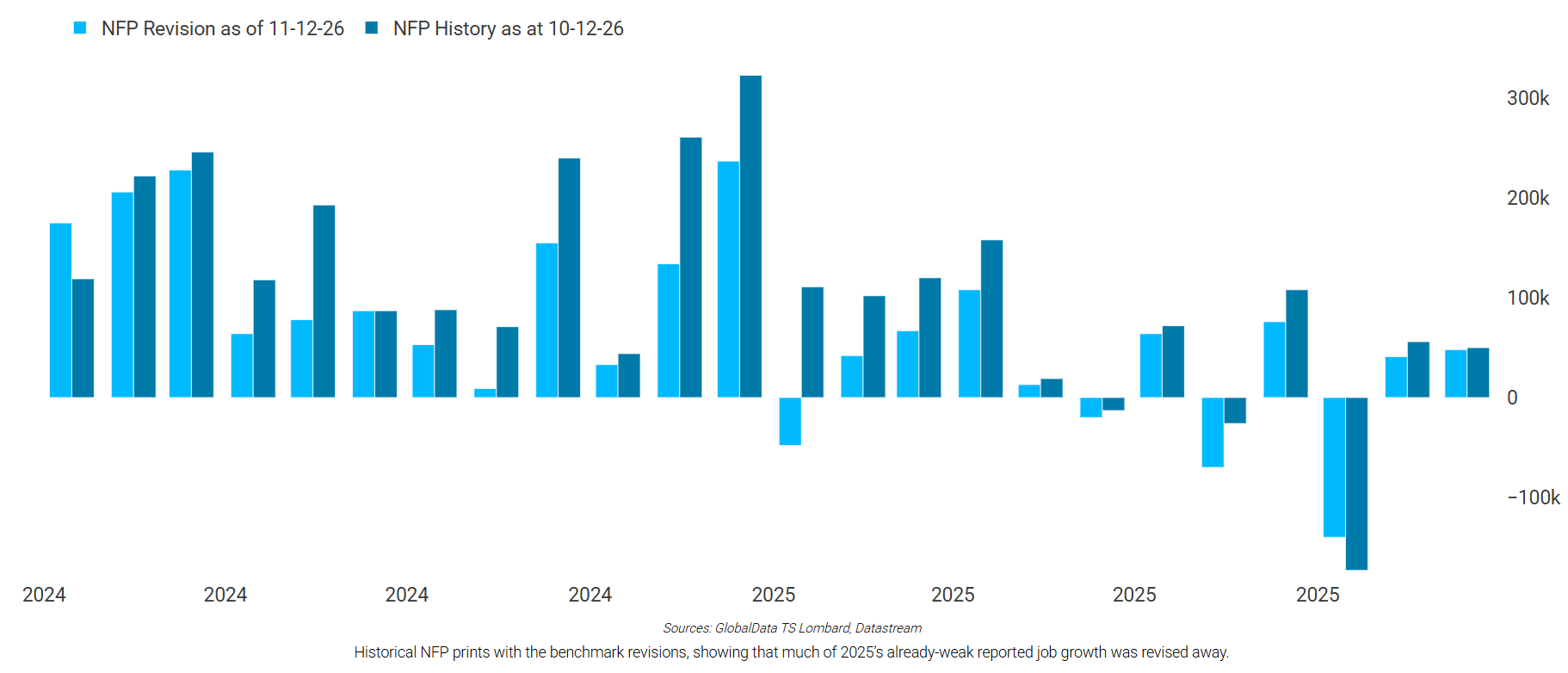

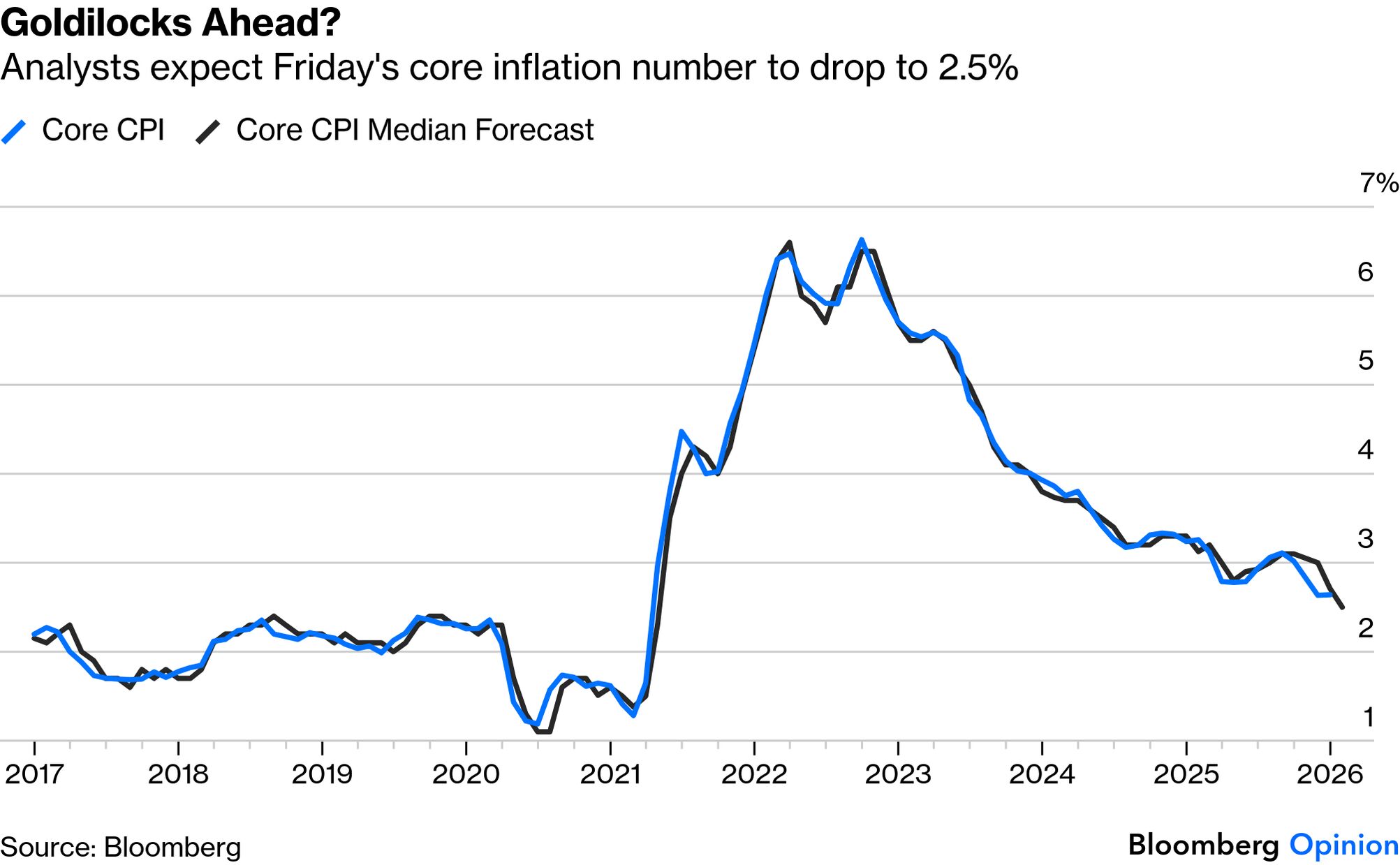

| Good economic news makes a pleasant change. Or does it? Wednesday dawned with traders braced for another decline in jobs growth. Instead, non-farm payrolls grew by 130,000 in January, better than any month of 2025, while the unemployment rate fell. That's evidently good news for the US workforce, and for those who've been arguing that the global economy is in something of a sweet spot: No news is ever unalloyedly positive, however. Strength like this in the jobs market makes further interest-rate cuts that much harder to justify. Futures pushed back the likely date of the next easing to July from June. That had a direct knock-on effect on bond yields, which rose sharply: Futures are still pricing in two cuts for the full year, but it's questionable whether that is a fair bet. The available workforce is smaller than it used to be, thanks to demographics. The ratio of those in employment to the entire population is unimpressive. But repeating that exercise for those in the prime working ages of 25 to 54 yields a very different outcome. For all practical purposes, the US appears to be close to full employment: All of this has to come with the caveat that payroll data is noisy and revision-prone at the best of times, and even more so after the shutdown forced government statisticians to down tools late last year. Freya Beamish of TS Lombard shows that much of 2025's already anaemic growth has been revised away: But she points out that the potential supply of workers has also been revised down, suggesting that the economy is still running close to capacity. The unwelcome corollary is the risk that any stimulus will be channeled into creating more inflation, still arguably the biggest political issue confronting the US. Projections in the swap market have risen a bit, but remain under control: The next big data release, taking the payroll's usual spot on Friday morning, will be January CPI. If the consensus of economists polled by Bloomberg has it right, core inflation will drop to a new post-pandemic low of 2.5%. In combination with the latest jobs numbers, that sounds almost like Goldilocks financial conditions — not too hot, not too cold — and would maintain the chance of rate cuts later this year: At the margin, however, the confidence in two cuts is beginning to look overdone, despite the president's clear expectation that Kevin Warsh, his nominee to take over the Federal Reserve chairmanship in May, will deliver at least this much easing. "The market is saying that Warsh will come in and cut twice," says Beamish. "That's certainly what he intends to do, but maybe the market won't be confident with him doing that later in the year." And there remains a more negative way to view the labor market. This is not a dynamic US economy and inequality is intensifying. Viktor Shvets of Macquarie Capital points to continuing low wage growth (with average hourly earnings now up 3.7% year-on-year), while gains flow mostly to those who already own assets: These factors are key to reconciling depressed surveys with strong output: People know they are falling behind, absolutely and relatively, and it is unlikely that middle-class jobs will ever come back. The immigration crackdown is making things worse, as immigrants are mostly complements not substitutes for local labor.

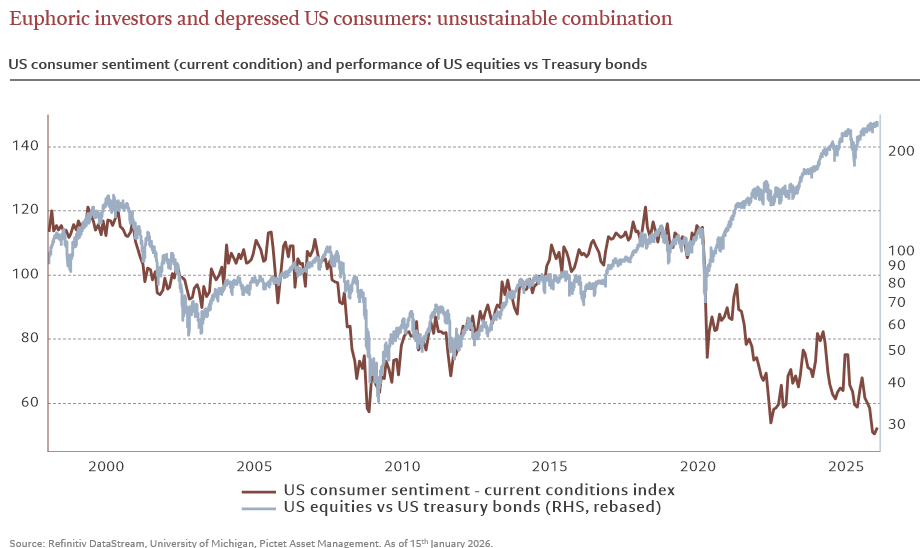

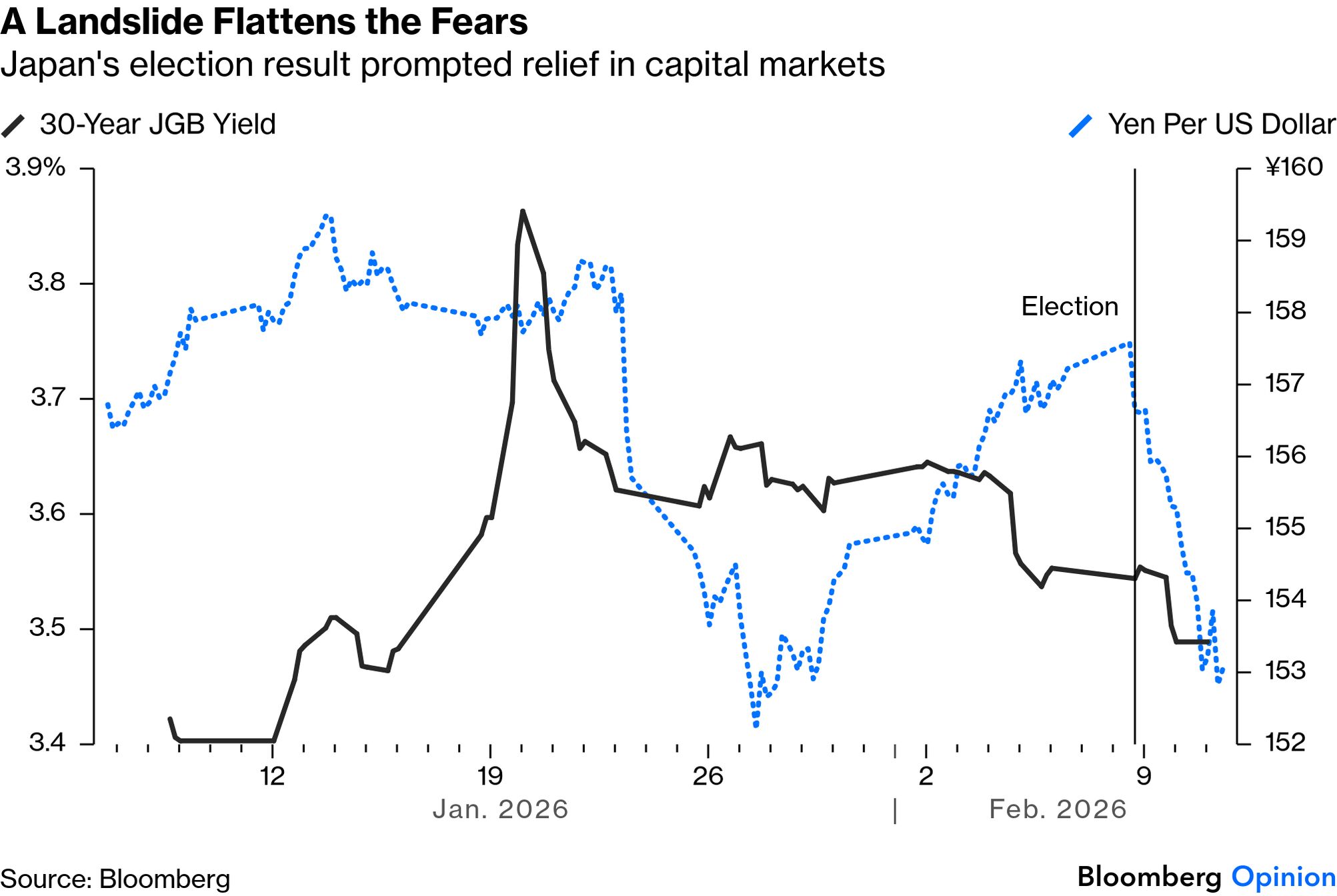

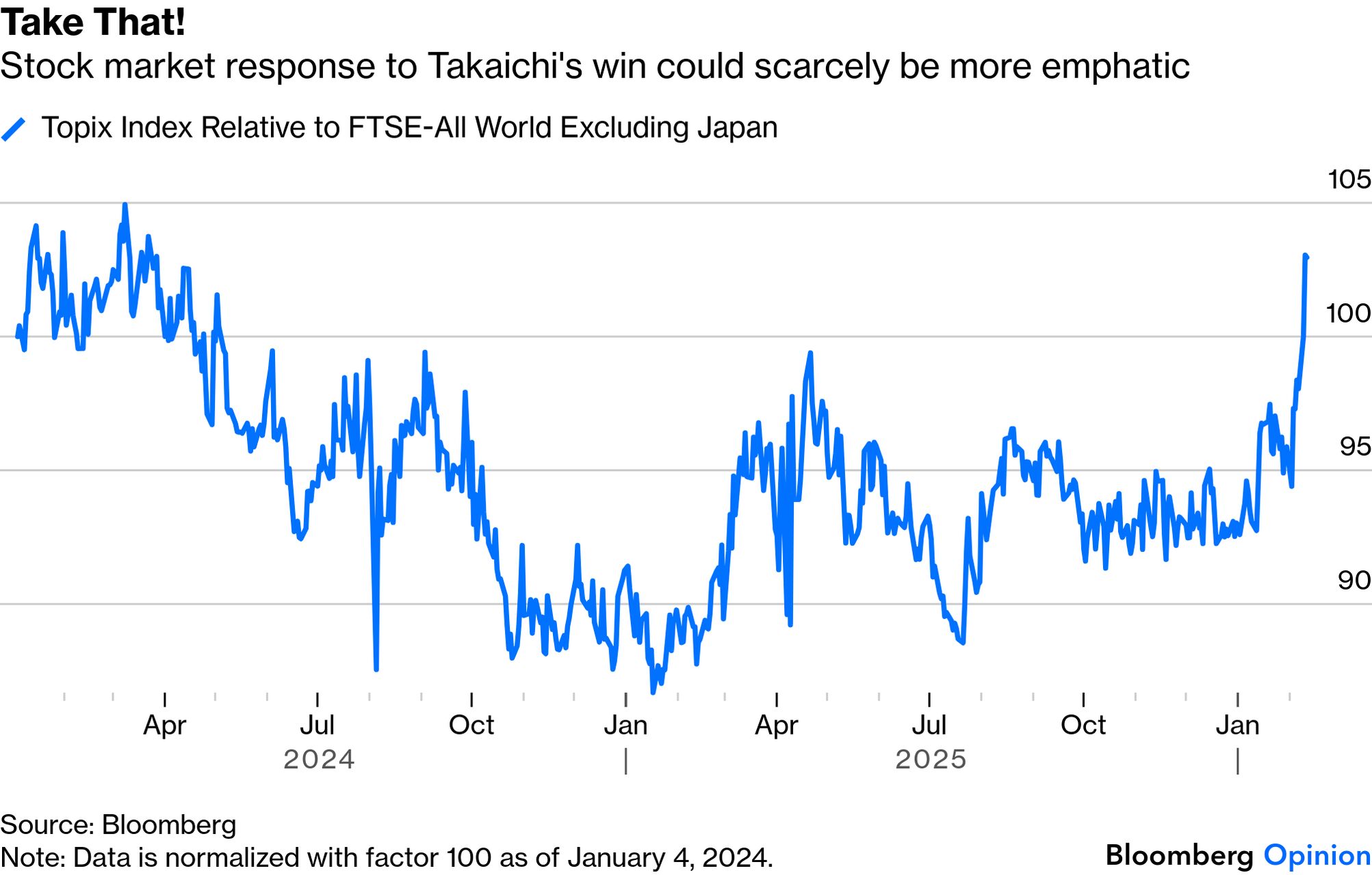

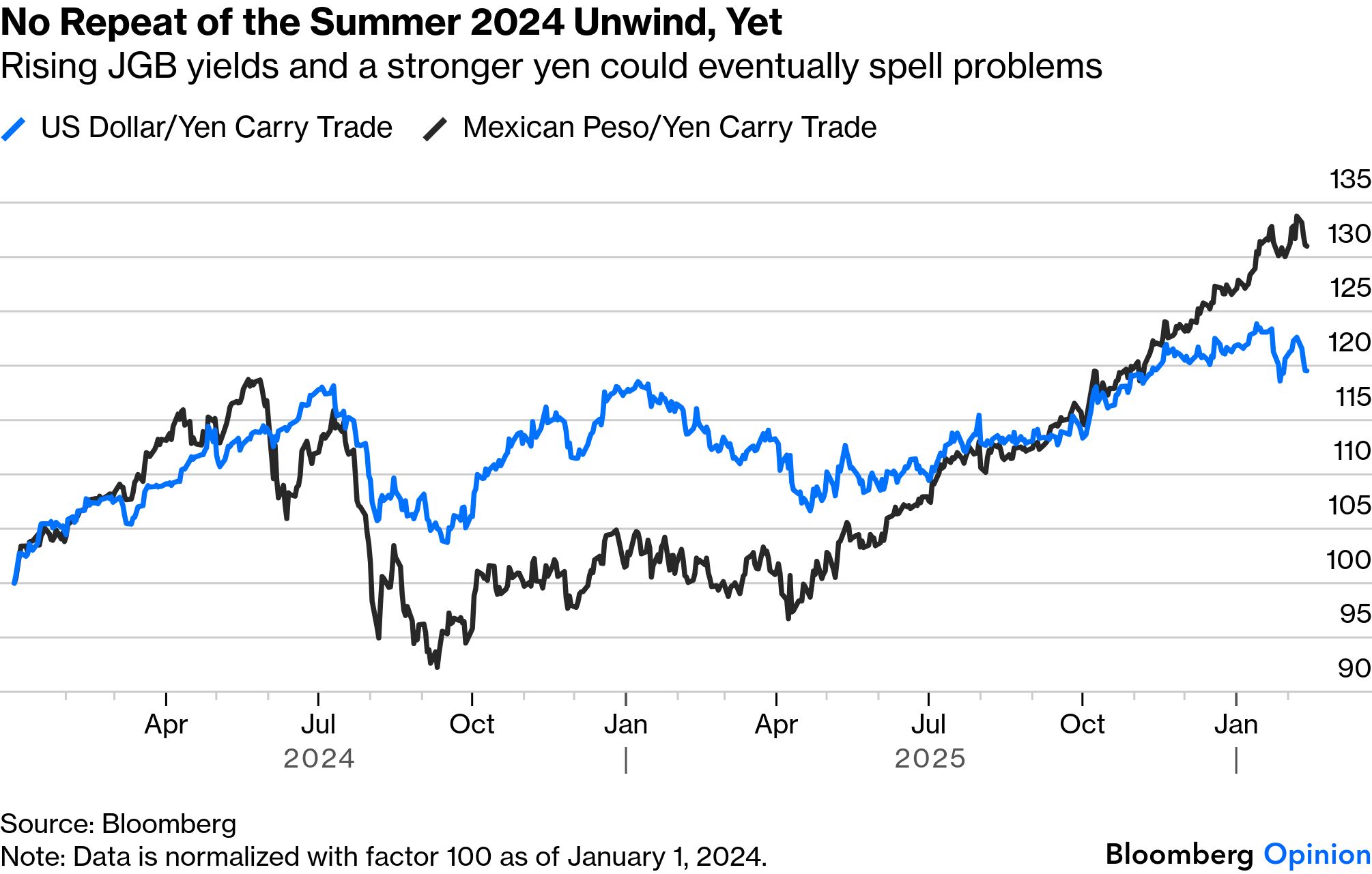

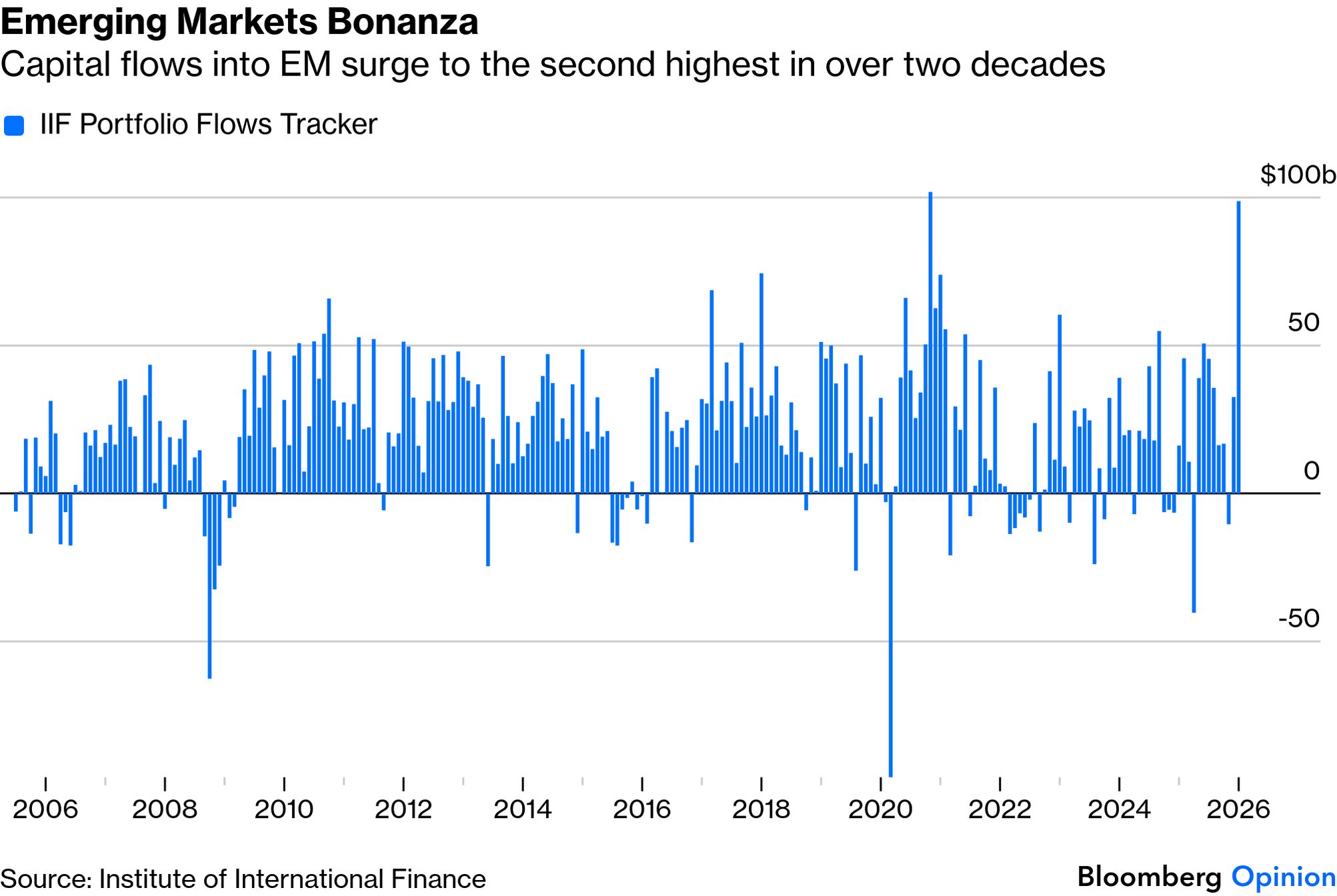

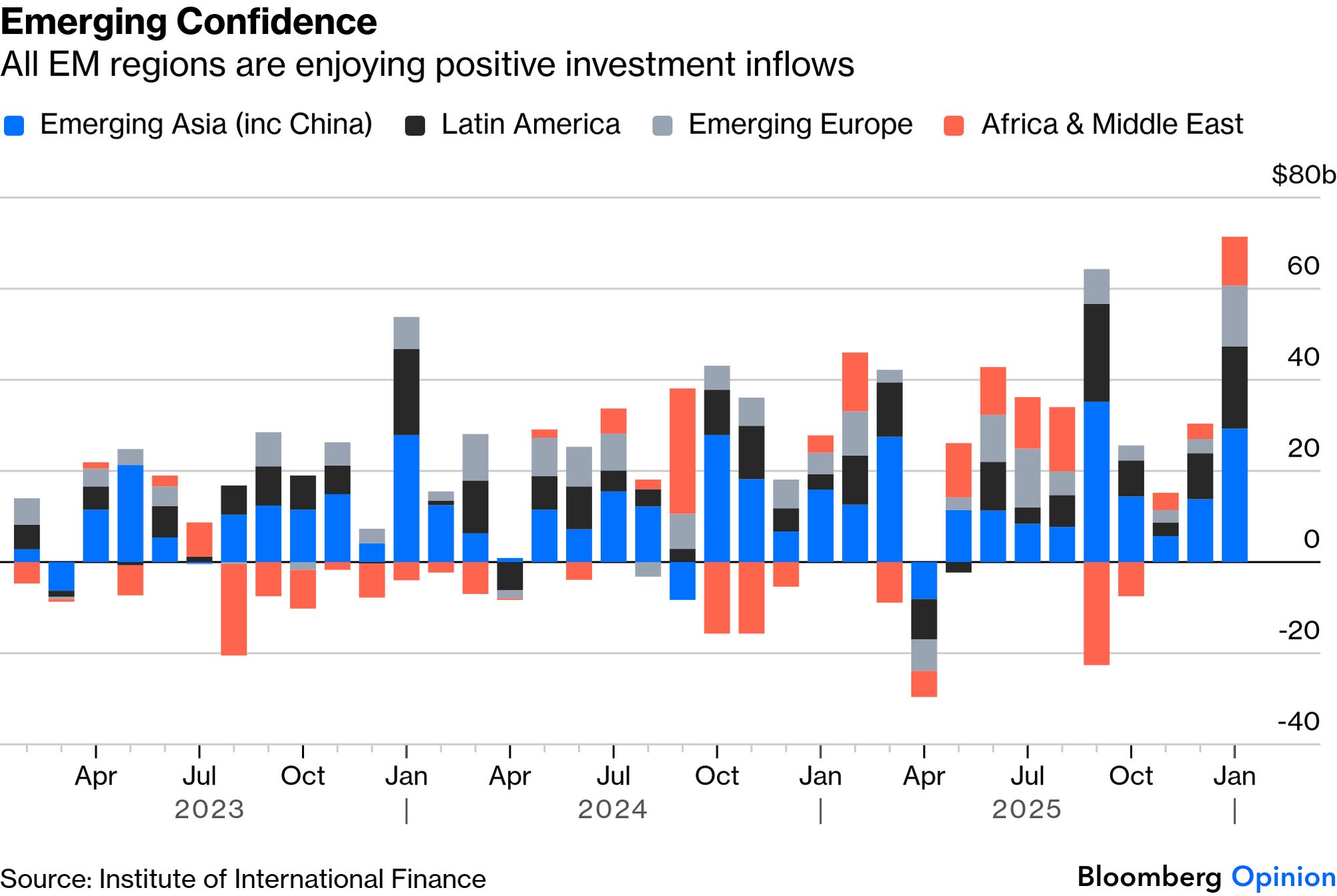

This helps explain the "K-shape" divergence between consumer sentiment and the stock market. Normally, they move together. Since the pandemic, the dispersion has been extraordinary, as demonstrated by this chart from Pictet Asset Management: It's hard to frame the biggest rise in employment in more than a year as anything other than good news. But many in the markets have managed to do it. Takaichi: So Far, So Great… | Markets are supposed to like gridlock, and dislike elections that give political leaders too much of a free hand. Except in Japan. Last month, Sanae Takaichi's campaign for prime minister prompted a sharp selloff in Japanese bonds, while the yen also fell — an ominous combination suggesting a lack of investor confidence. Then she won far more decisively than expected. The response has been a release of tension. The yen is back at ¥153, having dropped close to ¥160 last month, while 30-year yields are almost 40 basis points below their January high. What looked like a fast-unfolding crisis has been resolved, at least for now: That yen rebound has combined with a remarkable stock rally. Japan has now outpaced the rest of the world, even in dollar terms, since the start of 2024: None of this guarantees that Takaichi will fulfill all the hopes placed in her. And there are dangers in Japan's re-emergence, as demonstrated by the spasm that went through international markets the last time a yen appreciation drove an unwinding of the carry trade. So far, however, Bloomberg's index of the yen carry trades for the US dollar and the Mexican peso suggests that that effect is quite muted: By showing this degree of support, international investors are improving Takaichi's chances of success. But they are also raising the stakes for everyone should she fail to deliver. It's no accident that emerging markets have stirred back to life just as faith in US exceptionalism has wobbled. But the strength of their rally has exceeded almost all expectations, rivaling the strongest EM rebounds in history. In January, non-resident portfolio flows into EM assets, including equities and debt, climbed to nearly $100 billion. That's the second highest in the last two decades, topped only by one month post-Covid reopening in 2021, according to Institute of International Finance data. A year ago, inflows were only $16.2 billion: Previous surges were driven by a particular asset class or region. This one reflects coordinated inflows across debt and equity, China and the rest of EM (now widely considered separate due to the political issues surrounding Chinese investment): What can explain this? IIF's Jonathan Fortun credits primary market activity. Sovereign issuance was unusually front-loaded in early January, as borrowers took advantage of tight spreads and strong investor demand. That didn't crowd out investment in other assets, but recycled interest, particularly in hard-currency debt. Such broad-based appetite suggests emerging markets may finally have turned a corner. Further, this hasn't just been at the US's expense. Framing it that way would miss the idiosyncrasies of these diverse economies. Corporate USA still boasts fantastic fundamentals, and a range of dominant and innovative companies. Global X's Malcolm Dorson suggests that investors' renewed allocations into EM reflect a more nuanced calculation, as most were underweight: That doesn't mean you're necessarily dumping the US, but it probably means you're taking 3% to 5% out of the S&P 500 and putting it into emerging markets. You're still dramatically overweight the US, but taking some profits off the table. And because EM is coming from such a lower base, that capital is very meaningful and leads to market re-rating.

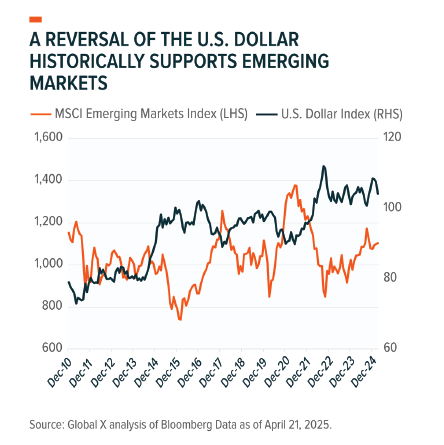

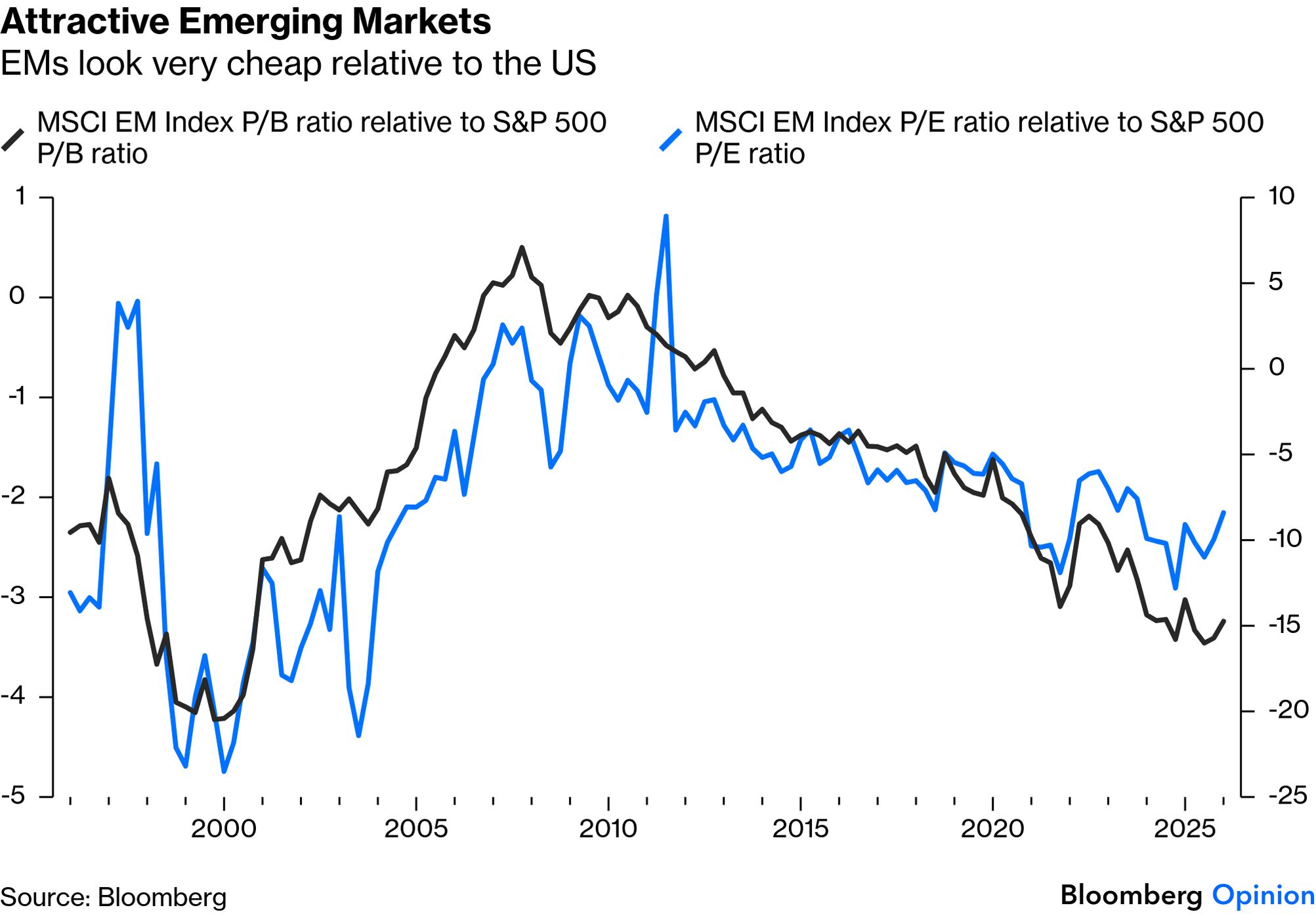

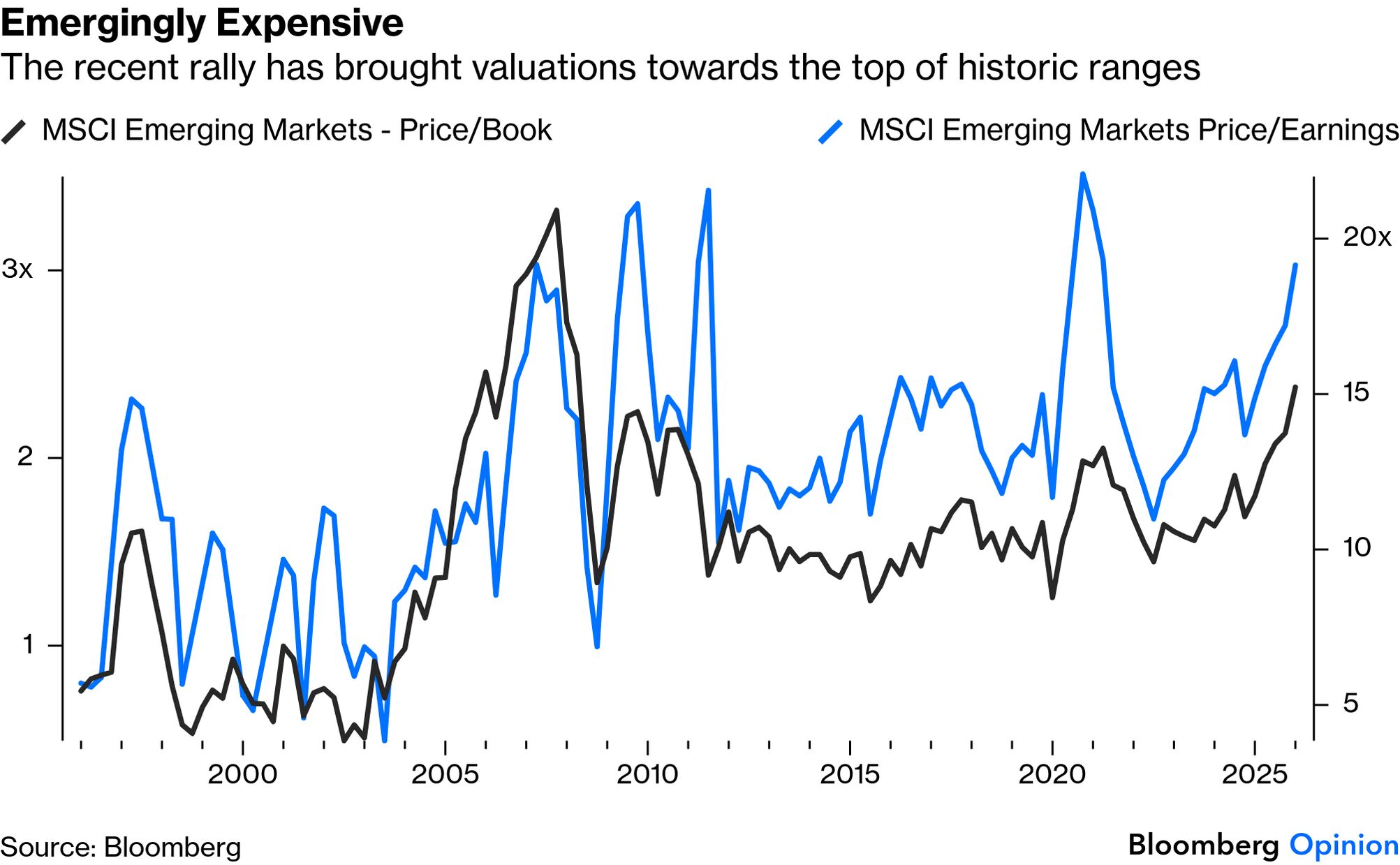

The weaker dollar enhances emerging markets' appeal, lifting carry-adjusted returns and supporting allocations to both local- and hard-currency debt. That helps explain the outperformance since the start of last year. This Global X chart illustrates the inverse relationship: Additionally, emerging markets valuations are relatively cheaper than the US. Historically, that wouldn't be enough to spark sustained outperformance. But combined with cyclical tailwinds, a weaker dollar, and growing scrutiny of US exceptionalism, the case for investors seeking diversification looks more compelling: That said, in absolute terms, the developing world is no longer convincingly cheap. Compared to book values, EM shares have only previously been more expensive during the 2007 rally that culminated in the Global Financial Crisis: Can this exceptional performance continue? It might just happen. Many emerging economies are well into easing cycles, and are benefiting from the trickledown effects of US Big Tech group's immense capital expenditures. That has driven an increase in earnings optimism. Pictet's Luca Paolini argues that faster earnings growth should make for a persuasive investment opportunity: As the AI rally broadens, Paolini identifies EM technology and communication services in markets such as Korea, Taiwan and China as best placed to profit from strong demand for hardware and semiconductors. None of this comes without risks. A bigger correction or bear market in the developed world would be a problem, and Paolini points to stretched US valuations. Renewed inflationary pressure could also strengthen the dollar and stall the momentum. For now, though, the strong earnings outlook and ample liquidity should allow the rally to carry on a bit longer. -- Richard Abbey |

No comments:

Post a Comment