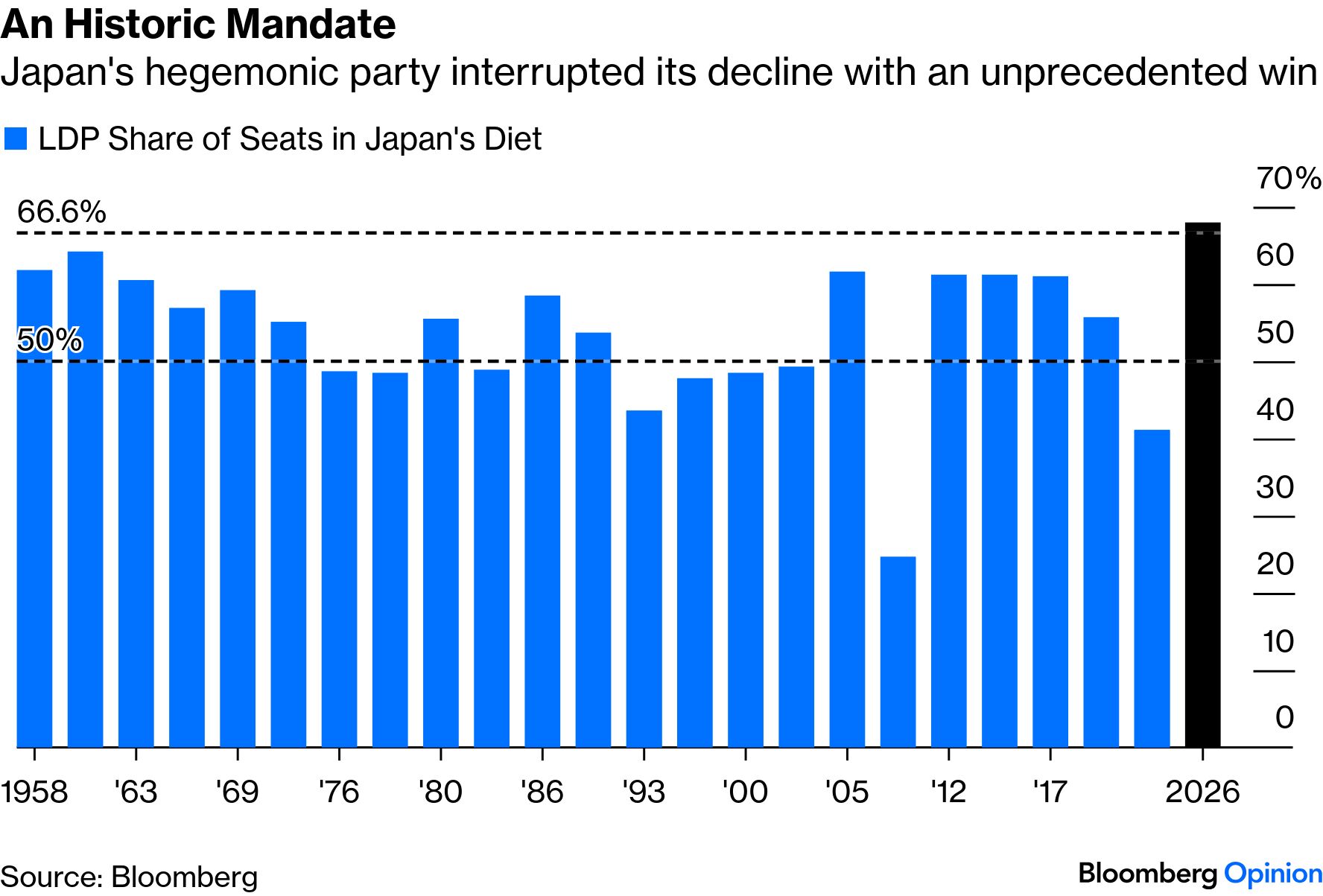

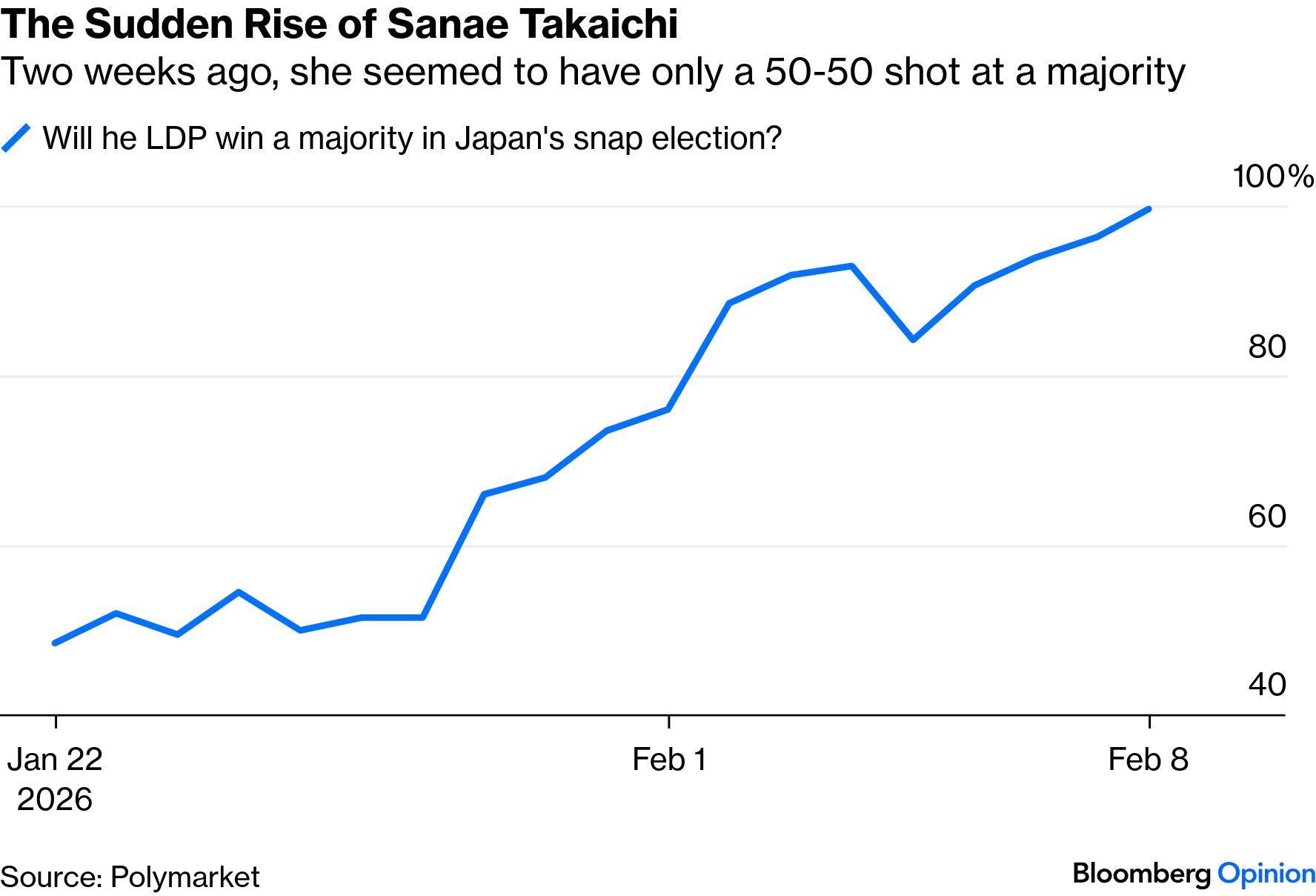

| Every so often, elections provide clarity. What just happened in Japan, however, is truly rare. Sanae Takaichi will be running the country for the next few years with minimal domestic impediments, and with a clear plan of what she wants to achieve. She has a mandate for it. Whether she succeeds or fails, Japan's critical role in the global financial system ensures that there will be consequences for everyone. This happened at breakneck speed in a country that had earned a reputation for inertia. Four months ago, Takaichi was seen as an outsider in the ruling Liberal Democratic Party's leadership election. The LDP itself was on the outs, losing its majority in the upper house and relying on shifting alliances to stay in charge. Now, not only does the LDP have power on its own, but it holds a two-thirds majority in the lower house — the first time this has ever happened. Takaichi is charismatic and forceful. Comparisons to Margaret Thatcher are apt, but Britain's Iron Lady never won a mandate this emphatic: To ram home how big a shock this is, her decision to call this election was a gamble. Barely two weeks ago, prediction-market betting put her chance of a simple majority, let alone a two-thirds supermajority, at barely 50%: The critical point after years of drift is that there is no question at all about who is in charge. The LDP runs the country and Takaichi runs the LDP. Her majority allows her to overcome not only legislative gridlock, but also bureaucratic inertia. For better or worse, what gets done will be what she wants. Veteran Japan analyst Jesper Koll of the Monex Group puts it as follows: Takaichi now has the LDP and the technocrats exactly where she always wanted them: the LDP is now beholden to her; and the elite technocrats now know she'll be in power for at least two or three more years…so they have no choice but to invest their career in her success.

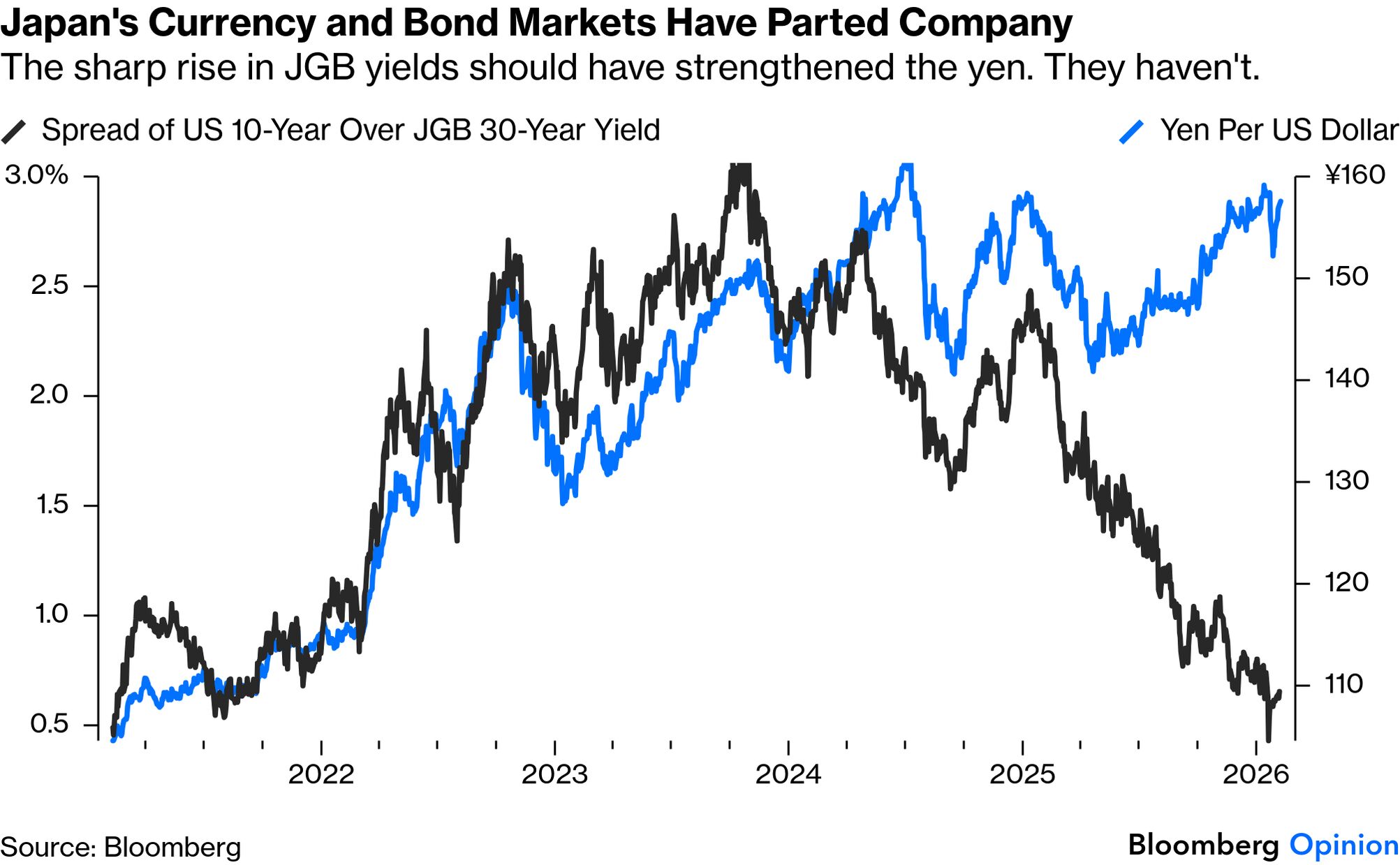

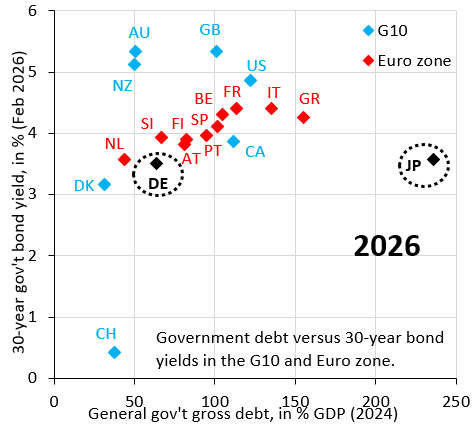

Where will Takaichi take her country? She is prepared to boost fiscal spending to help Corporate Japan reclaim some global influence, and she is aided by corporate governance reforms that have finally catalyzed quite a renaissance for old-line Japanese manufacturing companies. But she is hindered by skepticism in bond and currency markets, and by a recurrence of inflation. Stock markets as a rule like extra fiscal stimulus — the Nikkei 225 understandably surged more than 5% at the open of Monday trading. Japanese equities had already done well in the four months since she took command of the LDP. They have outpaced the rest of the world, even when the weak Japanese currency is taken into account: The problem comes with bonds and foreign exchange. Bond markets dislike extra borrowing. That will push yields upward. Generally, the currency should counteract this, as higher yields tend to attract funds into the country and strengthen the yen. That is not happening: On its face, this is alarming — when investors won't buy bonds, or hold the yen, those are the classic symptoms of lost international confidence. The advantage of the election is that power to respond is now firmly in one pair of hands. Robin Brooks of the Brookings Institution says that Japanese yields are artificially low given the country's high gross debt. They are still at the same level as fiscally frugal Germany: Brooks argues that the key will be to sell Japanese government assets, which would ease the problem; this should be easier to achieve given Takaichi's new power over the bureaucracy, but it remains to be seen whether she does it. Japan's approach should at least now be coherent. As it is, markets' fiscal concerns express themselves primarily in the weak currency, which moved little in early trading. The other immediate question is whether she will cut the consumption tax, as has been floated during the campaign. That would add to fiscal pressure. Jin Kenzaki of Societe Generale SA argues that the scale of Takaichi's victory makes it far easier for her not to go through with this "as cooperation with opposition parties that have long advocated a consumption tax cut will no longer be necessary." It's a fascinating and potentially risky situation. But with the buck plainly stopping with Sanae Takaichi, the chances look good that Japan can navigate its way through.

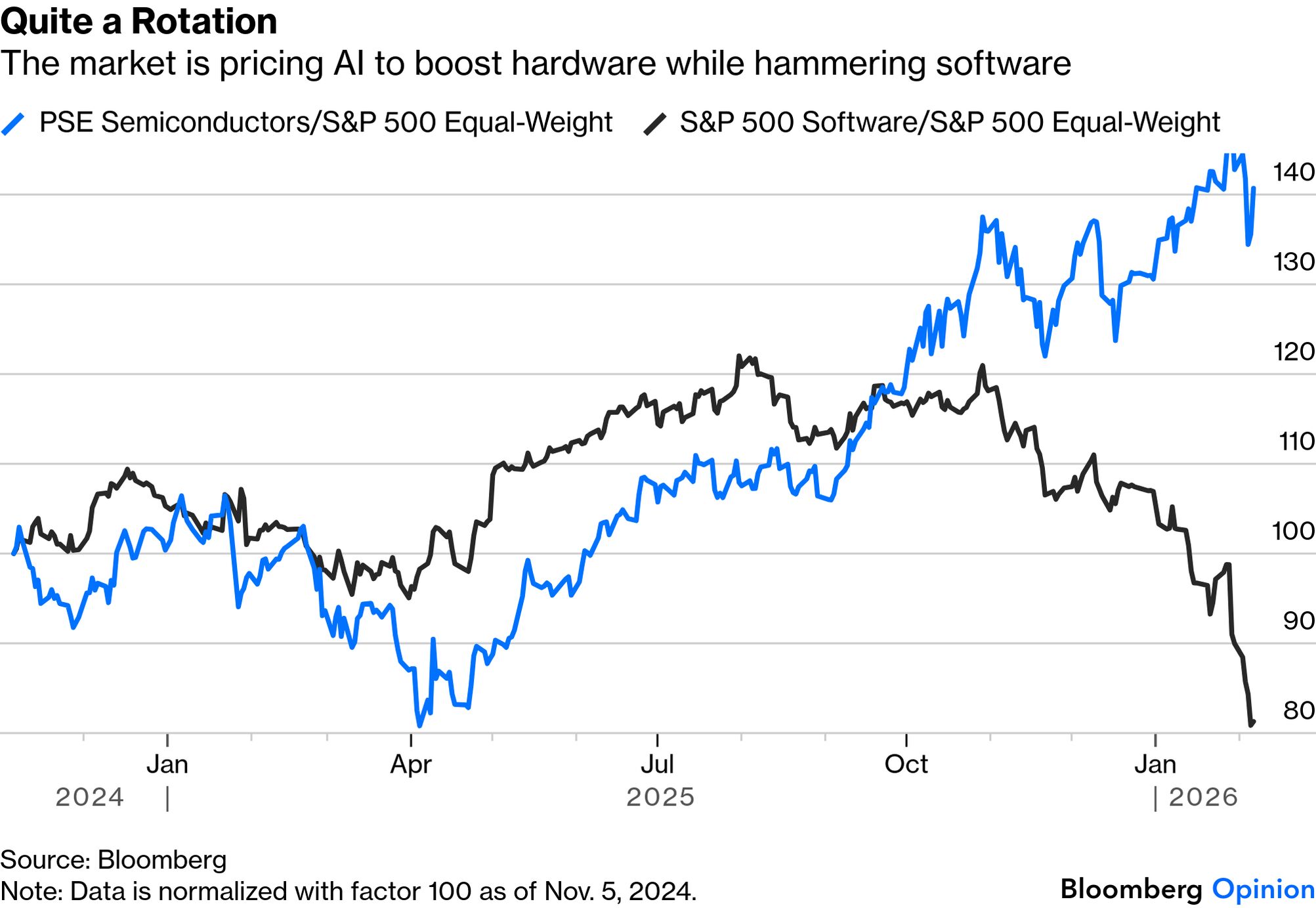

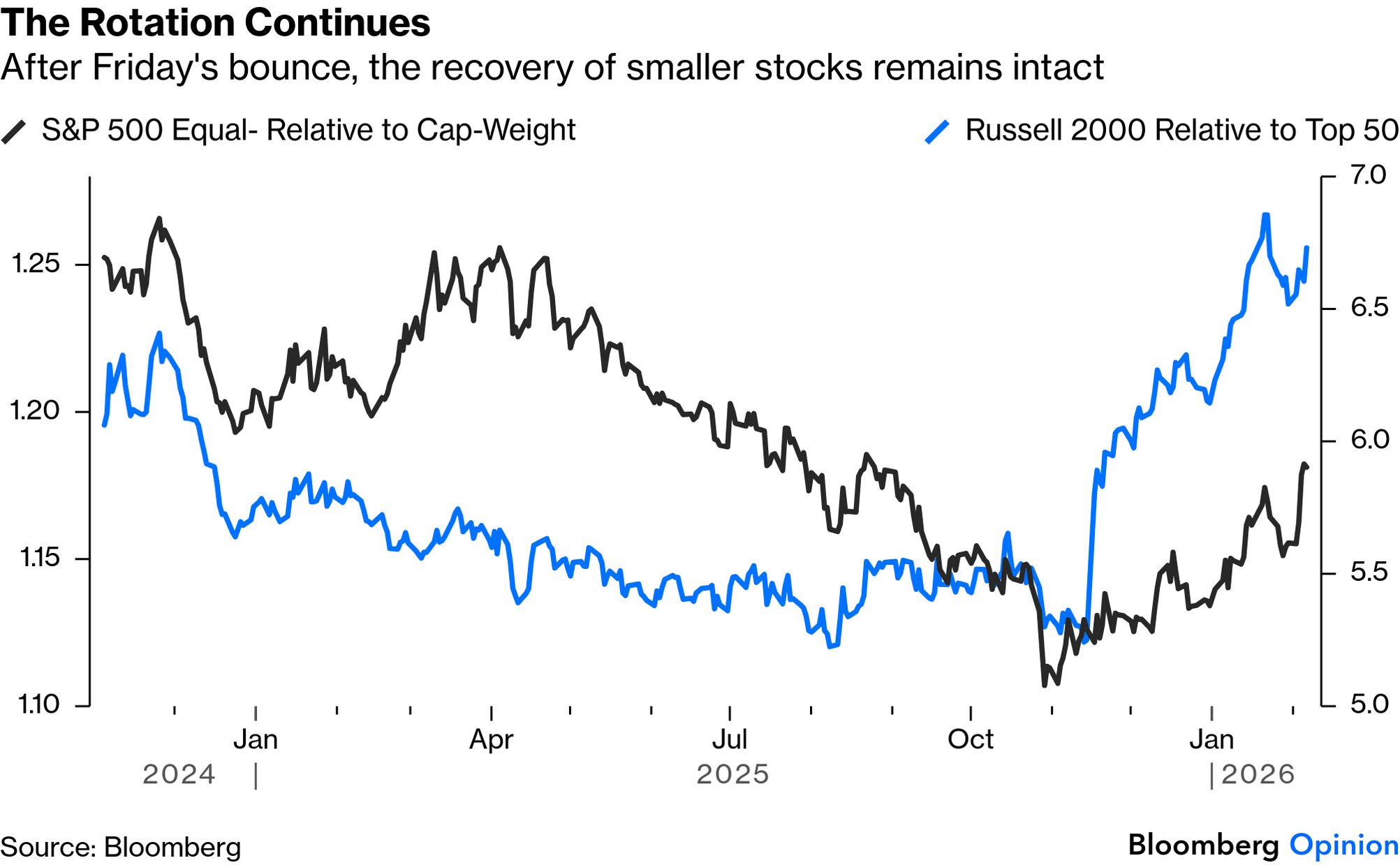

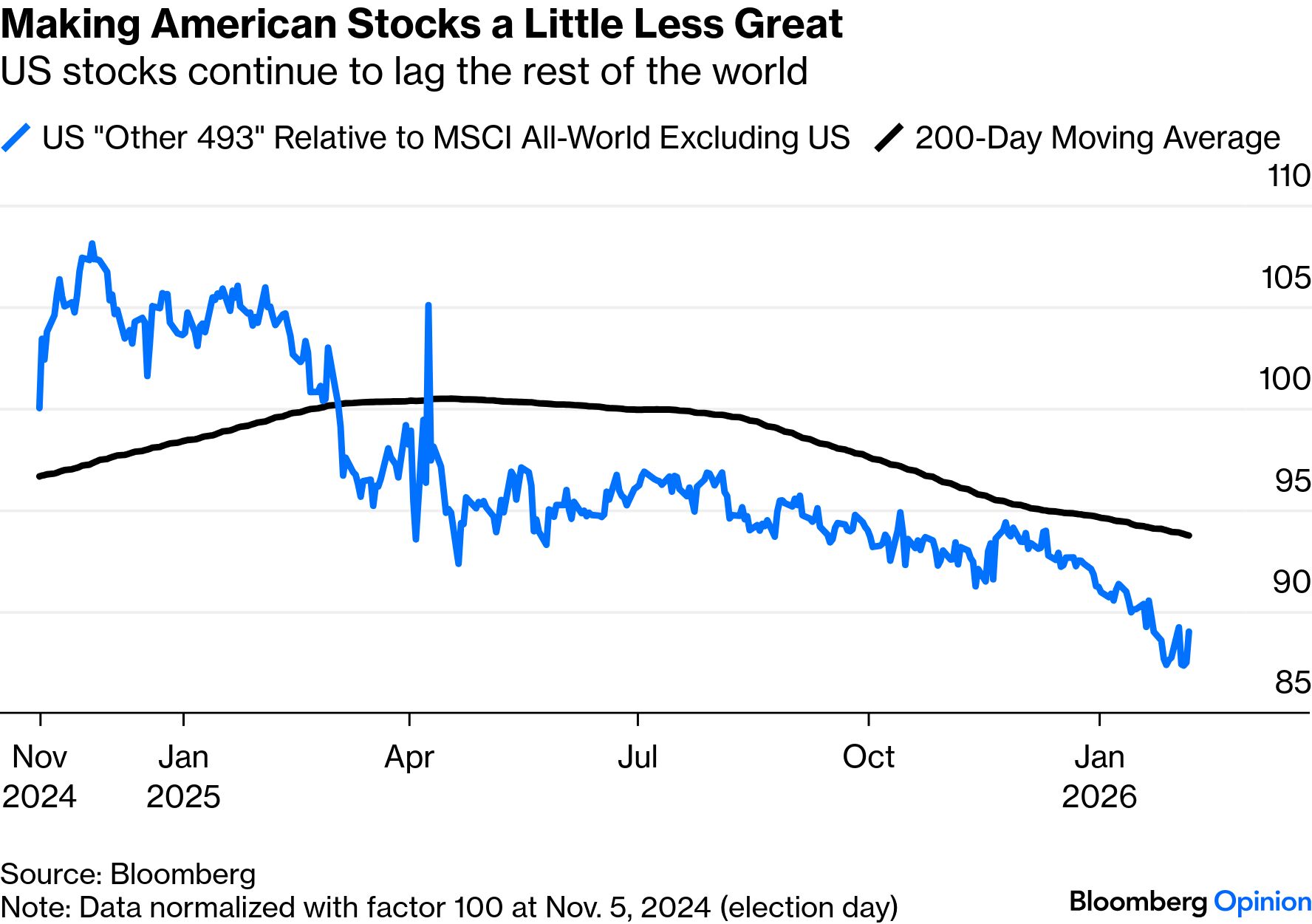

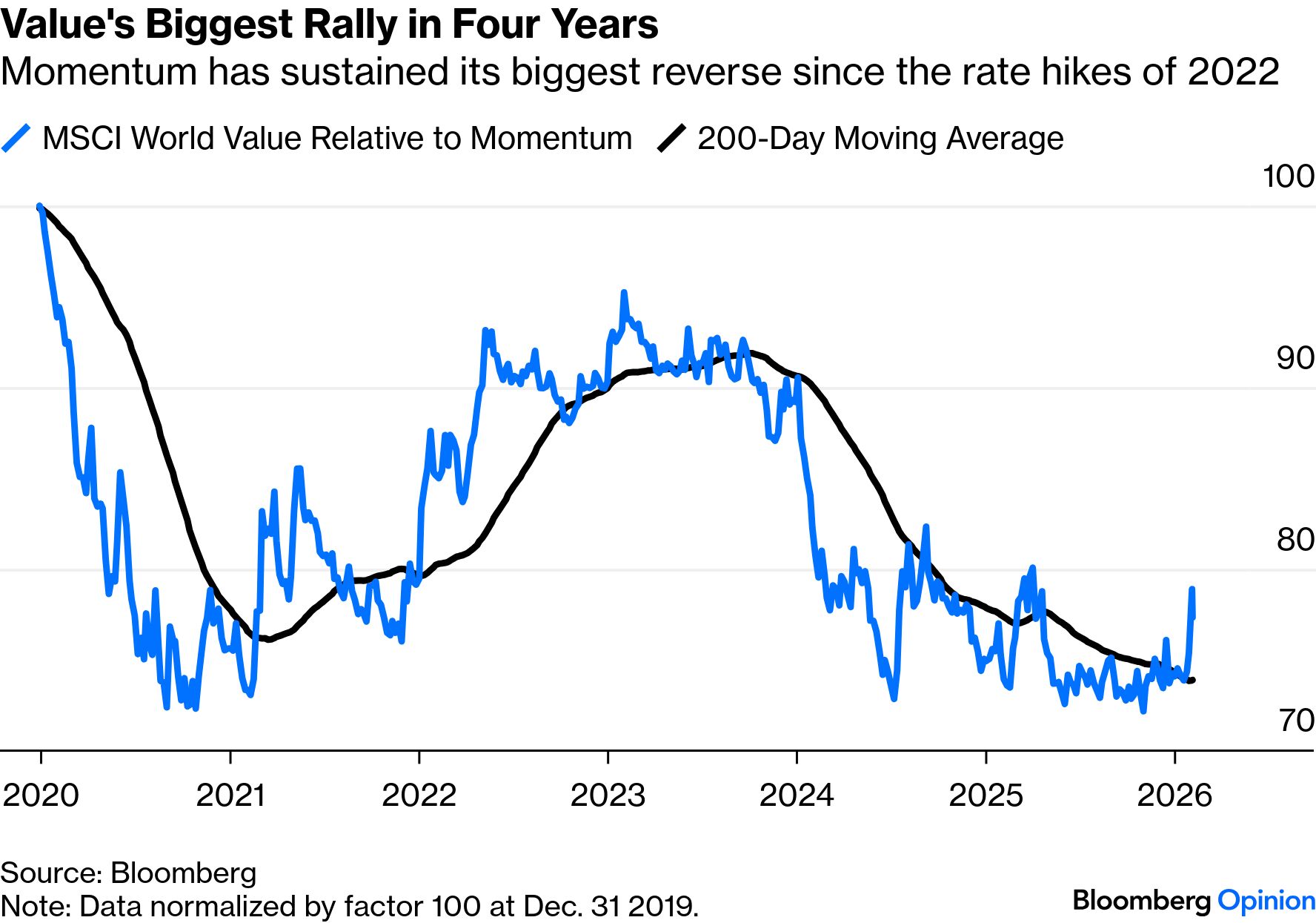

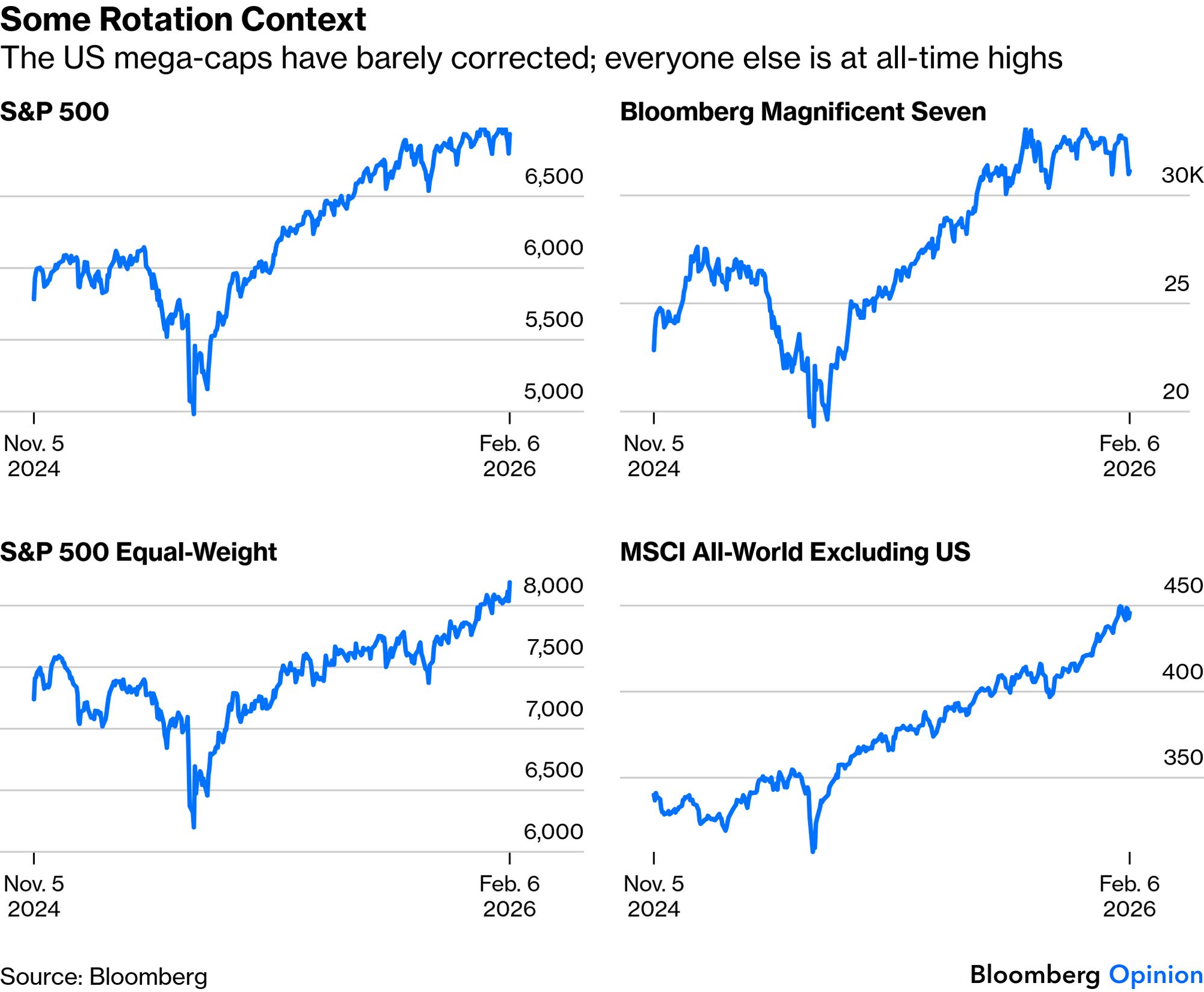

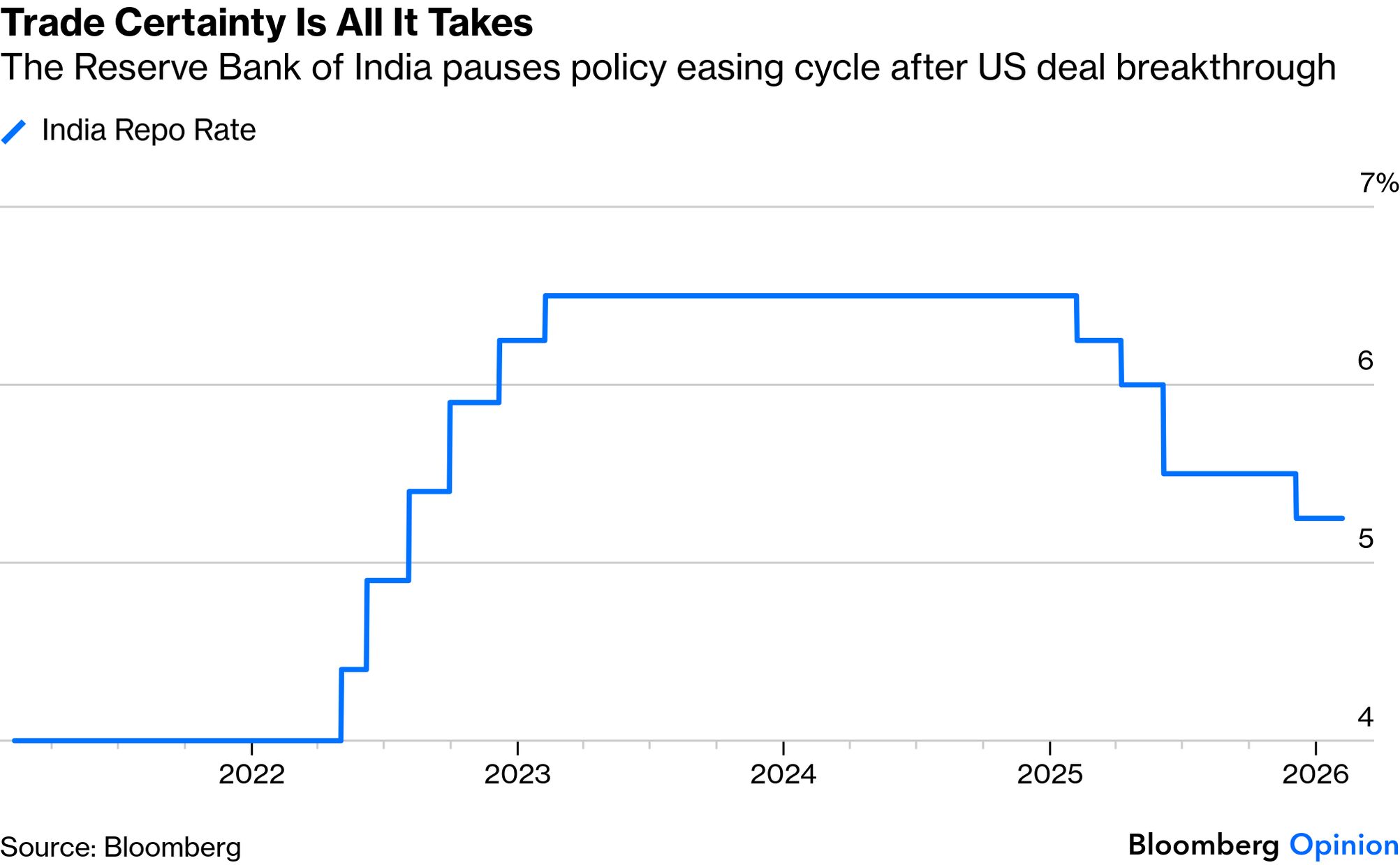

Rotation is the name of the game in US stocks. Even after a big switchback in favor of recent losers on Friday, market leadership has flipped dramatically in the last few weeks. The two key points are: 1) this is genuinely significant and 2) it might just prove healthy. Here are some charts to illustrate this. First, the market has turned against software stocks, even as chipmakers have continued to surge. The bet is that artificial intelligence will mess up the business models of the existing leaders, while requiring everyone to invest more in computing capacity: Despite recent losers regaining ground to end the week, the trends for the equal-weight S&P 500 (where each stock counts for 0.2%) to beat the mega-cap dominated cap-weighted index, and for small-caps to outrun the biggest remain firmly in place: The rotation out of the US and toward everyone else is also intact: And the rebound for value stocks compared to those with momentum behind them continues to look impressive. The trend is squarely upward in the clearest way since the rate hikes of early 2022 knocked back momentum trades: This is generally a positive. If value is doing well, it's because people think growth is in plentiful supply and they can afford to look for bargains. As there have been (very reasonable) fears about a bubble in AI stocks, there is room for this to continue. But the overall picture remains that this is a rotation and not a selloff. The S&P 500 and the Magnificent Seven tech platforms are down from their highs, but not in anything like a bear market. Broader measures of the stock market are at all-time highs: Upheavals like this always bring the risk that some institutions will be wrong-footed and create danger. For the time being, this rotation is overdue, and it would be healthy for it to continue. When India's central bank met last week to chart the path of interest rates, the task was well cut out. The country was in President Donald Trump's crosshairs, like many others, but with an added complication. New Delhi's dealings with Russia drew Washington's ire, culminating in a blunt cease-and-desist warning. But tireless efforts by trade negotiators were rewarded last week with a landmark deal, adding to an agreement with the European Union. The pacts eased macro uncertainty. Reserve Bank of India Governor Sanjay Malhotra said this allowed the bank to keep its policy rate unchanged at 5.25%, another pause in the easing cycle that commenced a year ago. Although "external headwinds" persist, he said, the deals boded well for the overall economic outlook: All else equal, upward revisions to the 2026 gross domestic product target look safer now that the tariff rate will fall to 18% from a punitive 50%. But without the full details, Gavekal Research's Udith Sikand and Tom Miller argue that optimism ought to be tempered. For instance, they question how India will replace discounted Russian oil with more expensive crude from the US and Venezuela. And even if goods exports to the US rebound soon, new immigration restrictions could hit services exports: Nevertheless, reduced uncertainty on the trade front should be positive at the margin for spurring investment from the private sector. There are signs that investment activity is picking up, including an acceleration in bank-credit growth and stronger industrial activity.

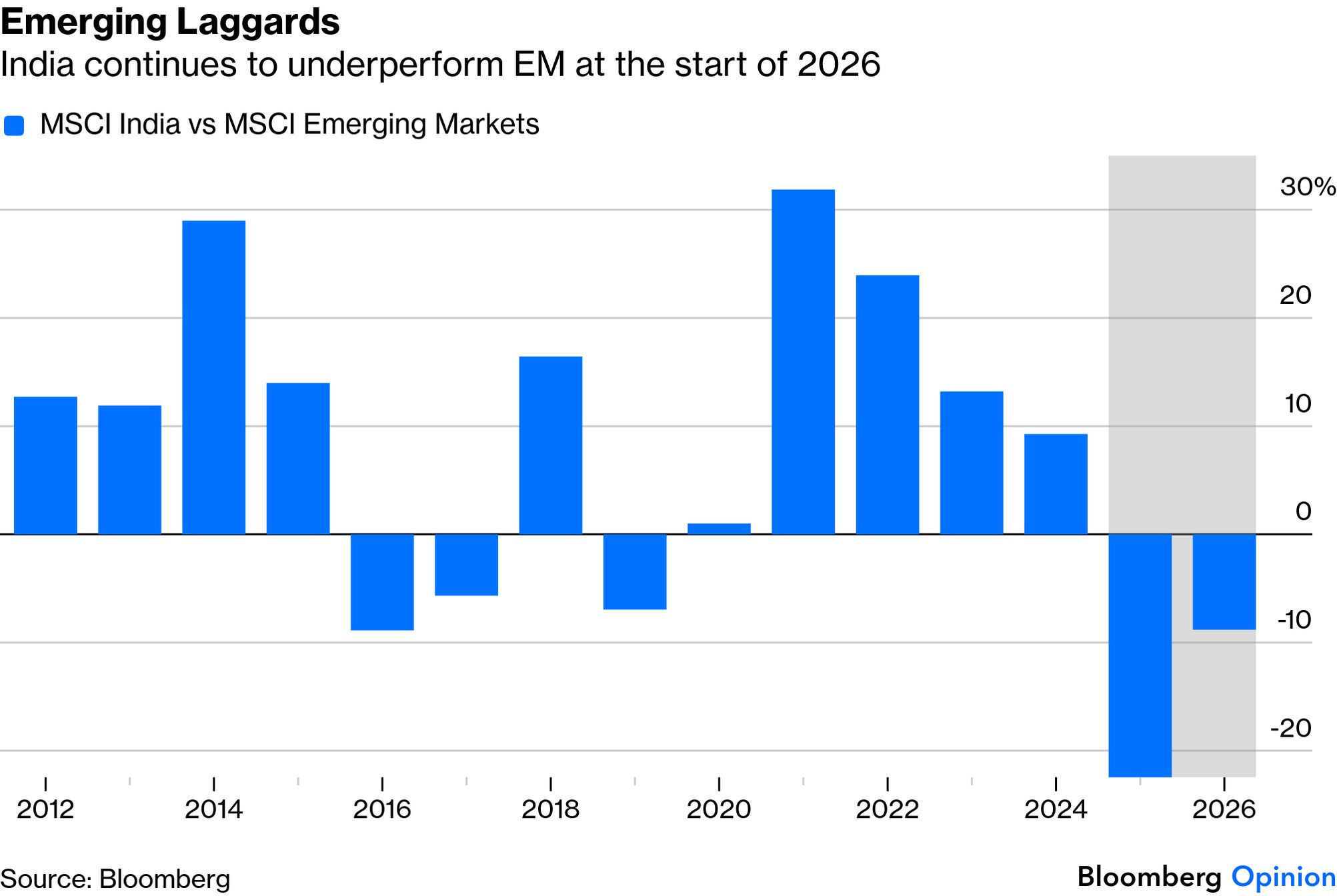

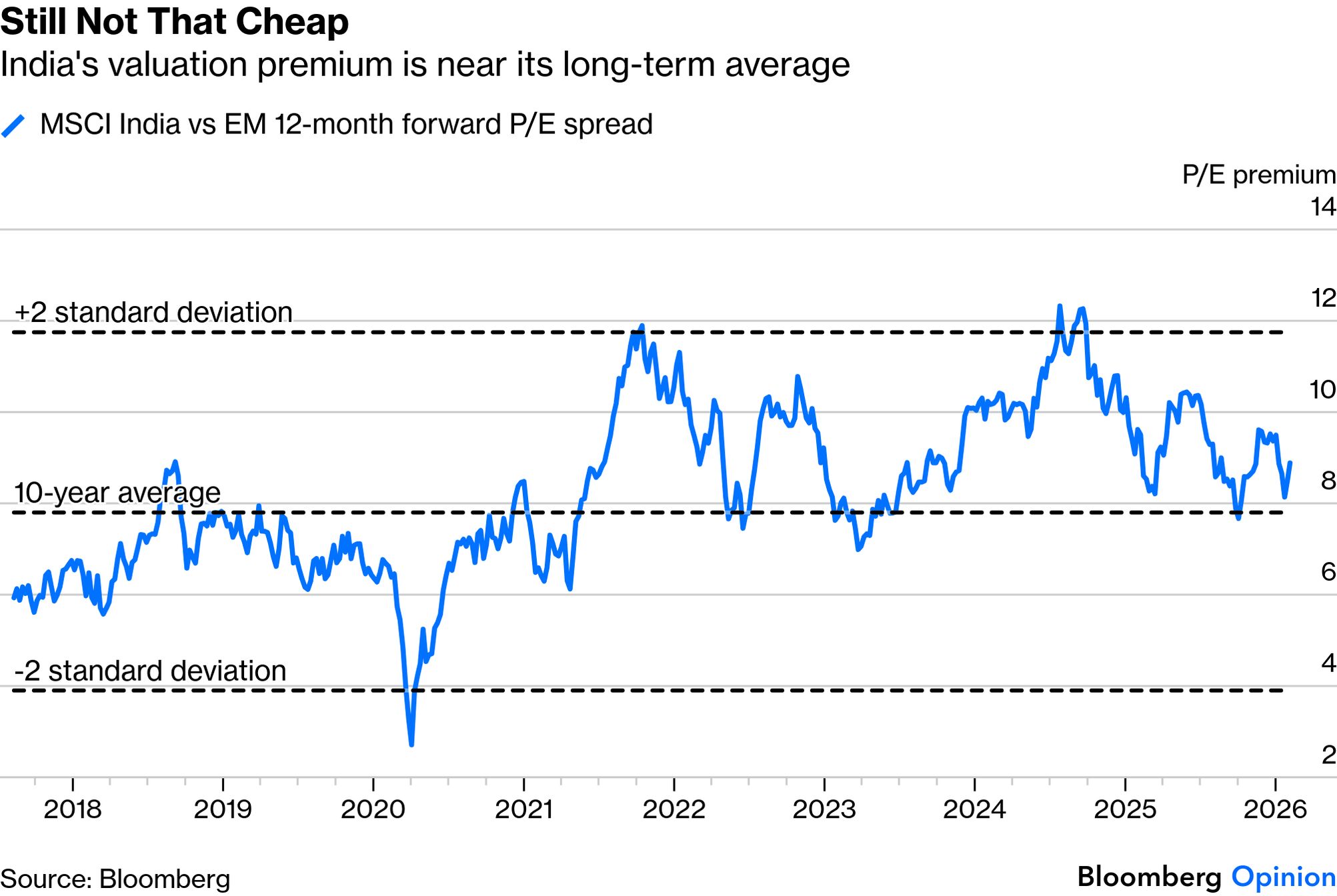

Sikand and Miller argue that the positive market reaction suggests the worst-case scenario for India's economy and asset prices is off the table. The central bank has less justification to return to monetary easing, and the rupee is unlikely to face sustained downward pressure even if investors are unhappy with the tax increases in last week's budget. For stocks, the question is whether reduced trade uncertainty is enough of a catalyst to spark pricey equities? The immediate aftermath suggests so. The deal's announcement last Monday jolted stocks back to life, with the Nifty 50 Index up 3.5% for the week: While the investor reaction is justified, the deals offer no panacea for weak corporate fundamentals. Indian stocks lagged global peers last month after poor earnings growth amid a weaker rupee last year brought an end to an impressive streak of outperformance: Bloomberg data show that the MSCI India earnings are projected to grow 8.3% over the next year, trailing regional peers. This stacks up against China's 16%, South Korea's 108%, and Taiwan's close to 30%. Trading at roughly 22 times forward earnings, India sits close to its long-term valuation average, which still makes it very expensive compared to other emerging markets: BNP Paribas Asset Management's Ecaterina Bigos argues for "a cautious optimism on Indian equities, with focus on strategic areas of growth for now." Further, the global software selloff complicates any chance that India's tech heavyweights such as Tata Consultancy Services Ltd. and Infosys Ltd. will serve as a catalyst for a broader surge in equities. This doesn't mean that the tariff cuts' effects on Indian equities will be short-lived. In theory, the deal could also attract portfolio investment, reversing record foreign outflows in recent months. While this is true, Gavekal's contention remains valid — the trade pact may have been a necessary condition for an equity rally, but it isn't a sufficient one. -- Richard Abbey |

No comments:

Post a Comment