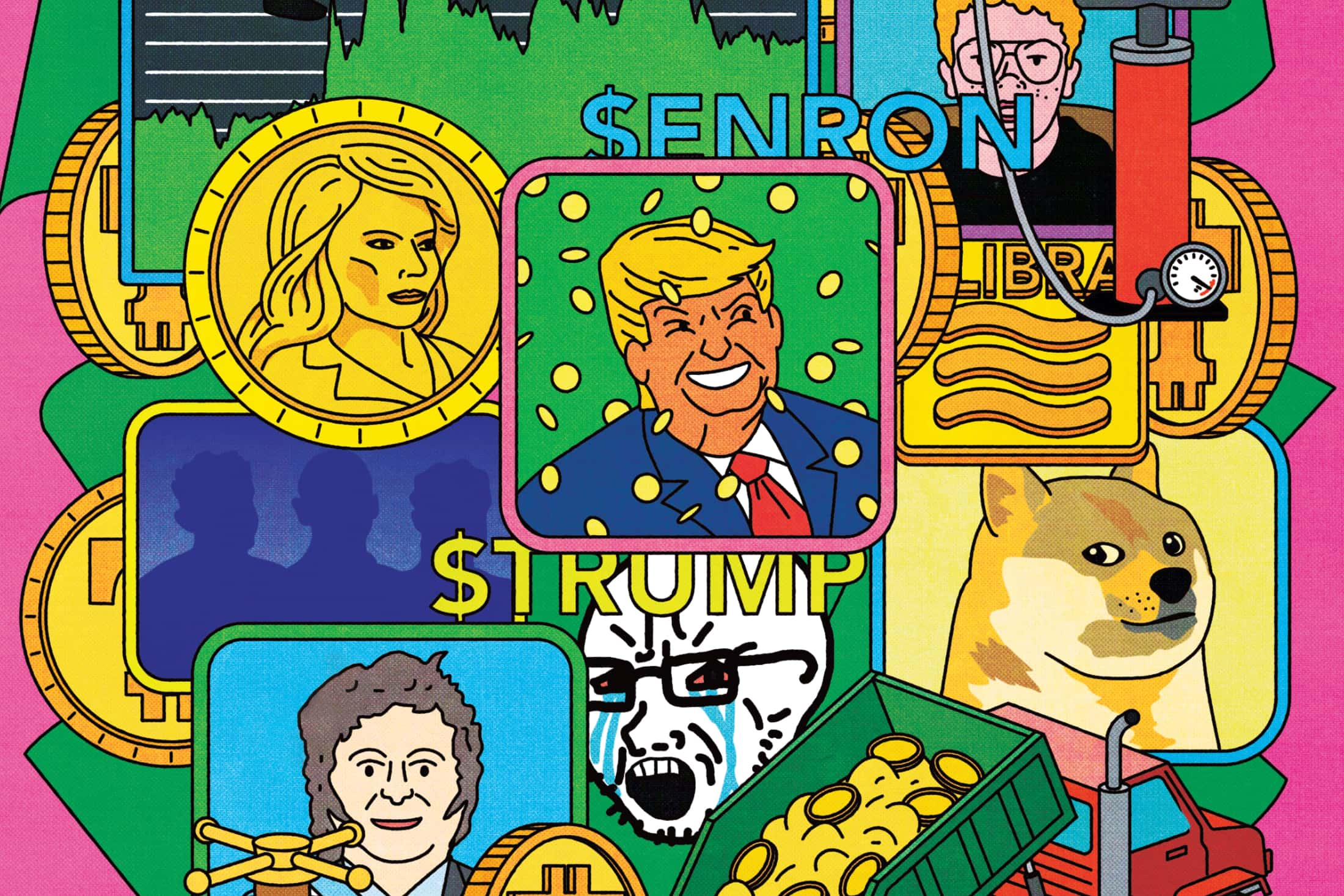

| AAA estimates that, for the first time, more than 8 million people will board US domestic flights this holiday season. That's a lot of people crowding airports and fighting over the lounge buffet. Bloomberg Businessweek senior reporter Amanda Mull writes today about JetBlue's lounge opening in New York amid airlines' push to recruit more lucrative customers. But first, Bloomberg News entertainment reporter Thomas Buckley looks at the legacy of actor-director Rob Reiner. Plus: How Donald and Melania Trump profited from memecoins, and a look at the low risk of a US recession. If this email was forwarded to you, click here to sign up. Rob Reiner, who first gained fame for playing Michael "Meathead" Stivic in the long-running sitcom All in the Family, evolved from one of the most recognizable television characters of the 1970s into one of the most revered comedy directors of the late 20th century. On Sunday, Reiner and his wife, photographer Michele Singer Reiner, were found dead at home. Their son Nick Reiner was arrested and charged with their murder. Rob Reiner's impact on the entertainment industry can be measured in awards and box office success, but perhaps most significantly in how it influenced other artists and popular culture.  Reiner on the set of When Harry Met Sally in 1989. Photographer: Allstar Picture Library Ltd/Alamy After winning two Emmy Awards for playing Archie Bunker's liberal son-in-law during the show's eight-year run, Reiner made his directorial debut with the 1984 comedy This Is Spinal Tap, a satirical documentary about a blundering heavy-metal band refusing to acknowledge its declining popularity. The movie is credited with popularizing the mockumentary format and later led to hit movies like Best in Show (2000), while its deadpan realism became a blueprint for comedy series such as The Office and Parks and Recreation as well as countless music parodies. Reiner also adapted the Stephen King novella The Body into the 1986 movie Stand by Me, which earned him his first Golden Globe nomination as a director. King told Reiner that it was "the best film ever made out of anything I've written." Reiner later directed two of the most celebrated comedies of the late 20th century. The highly quotable family adventure romp The Princess Bride (1987) was named one of the American Film Institute's 100 Greatest Love Stories of all time and was preserved by the Library of Congress for cultural and historical significance. The romantic comedy When Harry Met Sally, starring Billy Crystal and Meg Ryan, made AFI's list of funniest American movies. His most commercially successful film came in 1992 when he paired with screenwriter Aaron Sorkin to direct the military courtroom drama A Few Good Men, starring Tom Cruise, Jack Nicholson and Demi Moore. The movie, which grossed more than $240 million—about 10 times its budget—was nominated for four Academy Awards, including best picture. It was the only time that Reiner was nominated for an Oscar. Reiner's career was remarkable in its consistency as much as its range. Few filmmakers in Hollywood history have directed defining works across genres spanning comedy, romance, fantasy, courtroom drama and coming-of-age, and with so many titles succeeding in becoming cultural touchstones. —Thomas Buckley BlueHouse Enters the Lounge Scene | When JetBlue Airways Corp. announced last week that it would open its first airport lounge, the only real cause for surprise was the reminder that the airline hadn't built out a lounge network for its frequent flyers and big spenders a decade ago. But better late than never. BlueHouse, a 9,000-square-foot space across two floors of Terminal 5 at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York City, will open this week, with a second location to follow soon in Boston. Inside, JetBlue is promising a list of amenities that will sound familiar to anyone who's recently read a pitch for a high-end airline credit card: a food and drink menu curated by local chefs and mixologists, cozy seating, free Wi-Fi and quiet spaces to get some work done. You can easily guess who gets in: those who have spent their way into the airline's highest loyalty tier, holders of the most premium JetBlue Mastercard and flyers with Mint business-class tickets on its transatlantic flights.  The BlueHouse lounge in New York is scheduled to open Dec. 18. Source: JetBlue In her report on the announcement last week, my Bloomberg News colleague Sri Taylor noted that the lounge network is the latest addition to JetBlue's upmarket push, which the airline hopes will help it better compete for passengers in its main JFK hub and return it to profitability after a challenging year. Founded as a budget airline, JetBlue seems to have come to the same conclusion as most of its American competitors: Premium flyers are where the money's at. Even Southwest Airlines Co., the country's largest discount carrier, has begun developing a network of lounges. The major US carriers have lagged behind their international counterparts when it comes to luxurious service, though many have recently thrown serious cash and resources toward wooing high-value customers—largely business travelers, but also a growing cohort of pleasure travelers who've become more willing to fork out for bigger seats and better service, especially post-pandemic. These premium travelers can be four or five times more profitable per ticket than those flying on economy fares. So persuading more ticket holders to go upmarket makes the unit economics of air travel pencil out more easily than it otherwise might. The pitch doesn't just involve promises of comfort on the plane—increasingly, it includes ever-more-baroque airport perks such as a separate security line for the most premium ticket holders and full-service restaurants where the entire menu is free. But do you know what arguably helps the unit economics of running an airline even more than high-paying individual customers? Additional revenue streams. The story of America's increasingly luxurious premium travel business is not just one of fare classes and airport development, but also of premium credit cards, which, as I wrote last month in a Businessweek feature, are becoming far more influential in many corners of travel and leisure. A co-branded card program can bring in billions of dollars of annual revenue for an airline before a single jet is even fueled up, as Delta Air Lines Inc.'s lucrative, long-running partnership with American Express Co. does. The JetBlue Premier Mastercard, with its $499 annual fee, will be the simplest way to access the airline's new lounges for the average flyer, whose handful of ticket purchases per year would put them nowhere near the loyalty status necessary to get into the lounge the old-fashioned way. If you want to encourage sign-ups for high-fee credit cards, you need some carrots to dangle in front of potential customers. Over the past 15 years, access to airport lounges has proved to be such a powerful incentive that card issuers themselves built out networks to correspond with their premium cards—American Express's first Centurion Lounge opened in 2013, and Chase and CapitalOne now operate lounges, too, which provide cardholders with travel perks without making them swear fealty to any particular carrier. Airlines have responded in part by upgrading and expanding their lounge networks, with each opening promising more ornate amenities: shower suites with premium toiletries, massages, outdoor patios. Welcome to the arms race, JetBlue. —Amanda Mull Previously in the Businessweek Daily: First Class Gets Even More Opulent as Airlines Invest Billions |

No comments:

Post a Comment