| 🚗Uber pares back EV incentives for drivers and aligns with Trump

🏠What Zillow deleting climate scores shows about risk modeling

🔋Battery prices are projected to fall even further in 2026...

⚡...while grid tech stocks are expected to soar (it's not just AI)

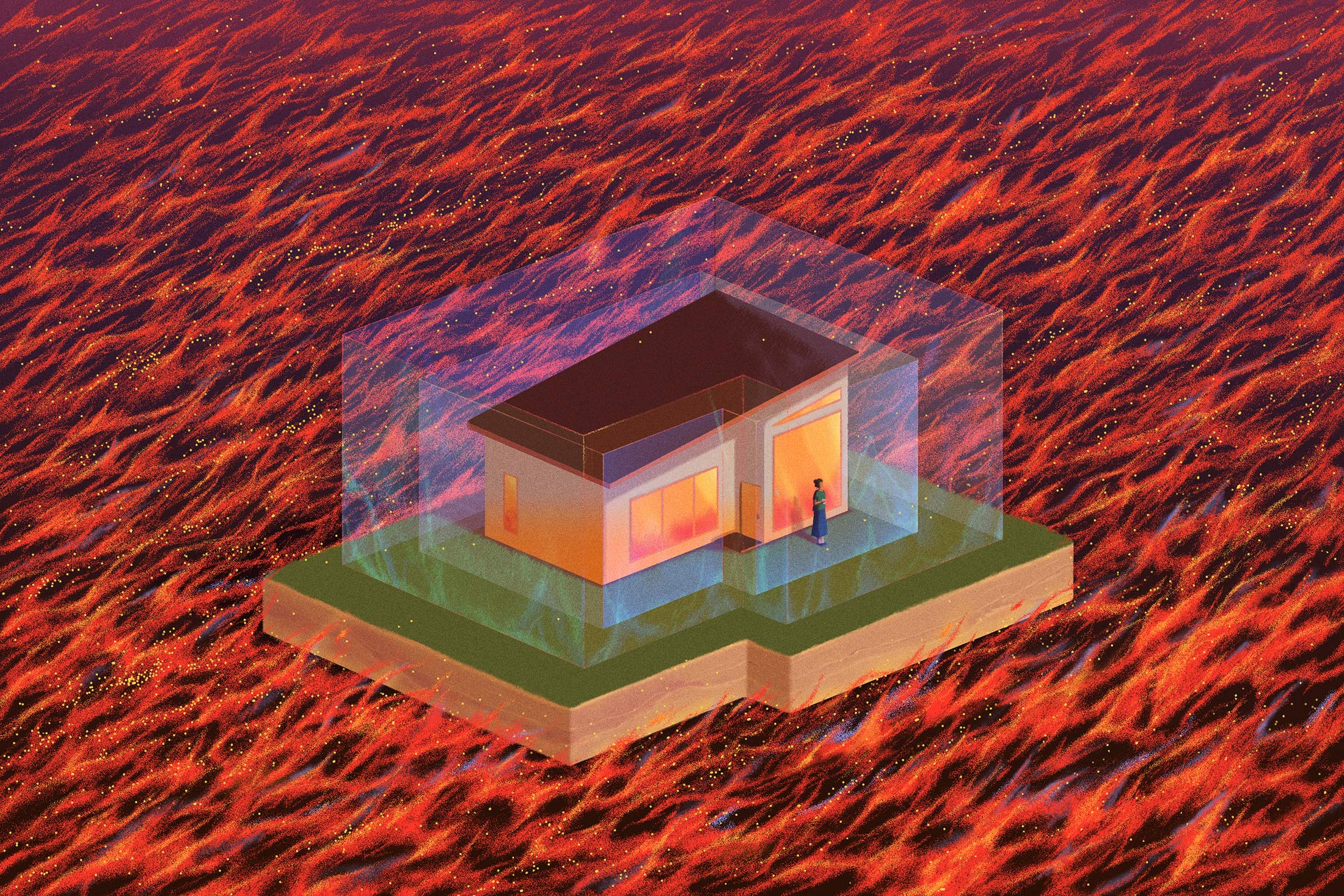

🌀This is the inspiration driving Trump's vision for disaster response When Canada elected Mark Carney as prime minister, there was hope that the country would pursue stronger climate policies. That hope was crushed after Carney signed a deal with the oil-producing province of Alberta that will roll back or dilute green regulations. As a result, Steven Guilbeault, Carney's culture minister has resigned from cabinet. He was the environment minister under Justin Trudeau and responsible for many of the policies at risk. This week on Zero, Guilbeault tells Akshat Rathi why the Alberta deal was the last straw. Listen now, and subscribe on Apple, Spotify or YouTube to get new episodes of Zero every Thursday. The fossil fuel and nuclear industries haven't exactly been friendly. After all, both provide baseload power, putting them in competition to sell electrons on the grid. But the rise of renewables has created a "the enemy of my enemy is my friend" moment. Many supporters of nuclear and fossil fuels have teamed up to counter the rise of renewable power. Attacks on offshore wind have proven particularly damaging, dovetailing with the Trump administration's assault. This weekend's excerpt comes from an investigation by Monte Reel and Mark Chediak into the burgeoning alliance and its attempts to quash the offshore wind industry. Their story follows reporting on how the backers of a politically connected nuclear startup are working, at times covertly, to neutralize the industry's chief regulator. For more investigations that expose unseen connections, please subscribe to Bloomberg News.  A wind turbine off of Virginia Beach in 2023. Photographer: Kendall Warner/The Virginian-Pilot/Getty Images The towering smokestacks of the Indian River power plant have been etched on the horizon of Delaware Bay for more than 60 years. From its opening in 1957, the plant burned tens of millions of tons of coal, sending pollution over thousands of homes and toxic ash into the groundwater. About 20 years ago, residents began joining in opposition. They collected health data from downwind communities; their findings prompted Delaware to officially designate the area a cancer cluster and led the plant to start downscaling operations. Last year the administration of Joe Biden, whose summer home is about 14 miles northeast of the plant, approved a plan that reimagined the site. The project called for putting a substation next to it that would distribute energy from more than 100 wind turbines to be built about 10 miles out to sea. The last of the plant's four coal-burning units was already scheduled to shut down for good within a year. Renewable energy would take the place of coal. David Stevenson had something different in mind. A former executive for the DuPont de Nemours Inc. chemical company, he worked for the Caesar Rodney Institute, the Delaware affiliate of the State Policy Network (SPN), a national consortium of think tanks aligned with, and partly funded by, fossil fuel interests. On behalf of the institute, Stevenson, 77, campaigned against electric vehicle subsidies, national ozone standards and a carbon tax. But Stevenson's main target of opposition has been offshore wind energy. Up and down the East Coast, from Nantucket to North Carolina, he's been involved with nonprofits with names that wouldn't look out of place alongside a Greenpeace bumper sticker: Save Our Beach View, ACK for Whales, Protect Our Coast NJ, the American Coalition for Ocean Protection. He also started the Ocean Environment Legal Defense Fund, designed to help anti-wind groups finance lawsuits against individual wind proposals. One challenged the project near Indian River, owned by US Wind Inc. Among the lawsuit's plaintiffs were Stevenson and a Delaware beach town, Fenwick Island. In January, two weeks before Donald Trump returned to the White House, Stevenson sent an email to the mayor of Fenwick Island with some proposals that might reverse the fate of Indian River, which would close its last coal unit one month later. He attached two documents to the email. The first was a draft executive order he'd written for officials connected to the incoming Trump administration. (Stevenson had served on Trump's first transition team, after the 2016 election.) Among other recommendations, it called for the federal government to stop approving leases for offshore wind projects and cancel all existing leases for projects that hadn't yet been completed. The second attachment was a policy recommendation for incoming Delaware Governor Matt Meyer titled "SMR Nuclear Proposal." (SMR stands for "small modular reactor.") It proposed that the governor allow Indian River to be sold to a nuclear power operator instead of being turned into a wind project. He told the mayor, who shared his opposition to the project, that he wasn't widely circulating the documents. "I want Trump and Meyer to get the credit," he wrote, "leaving a better chance they'll do as requested." |

No comments:

Post a Comment