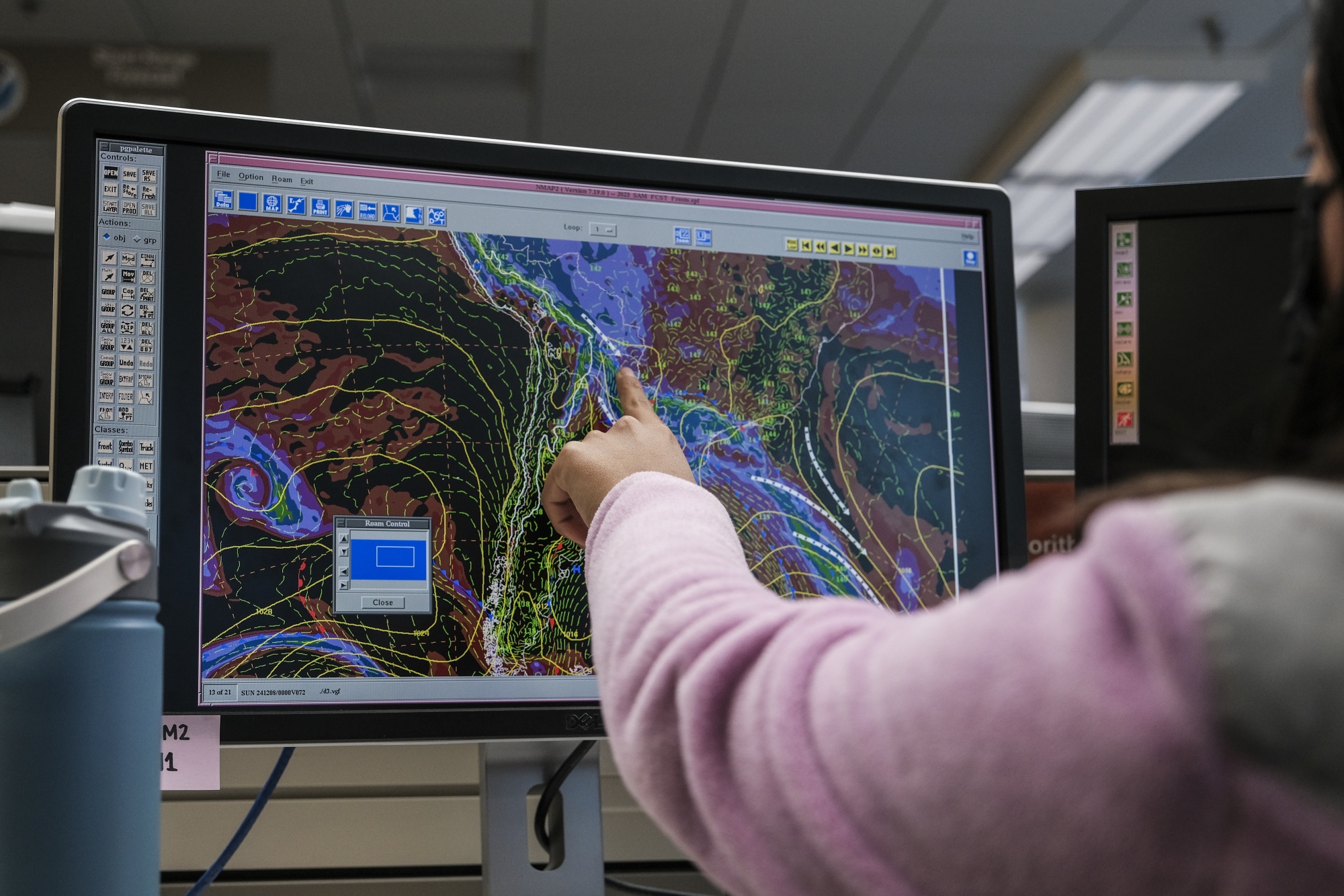

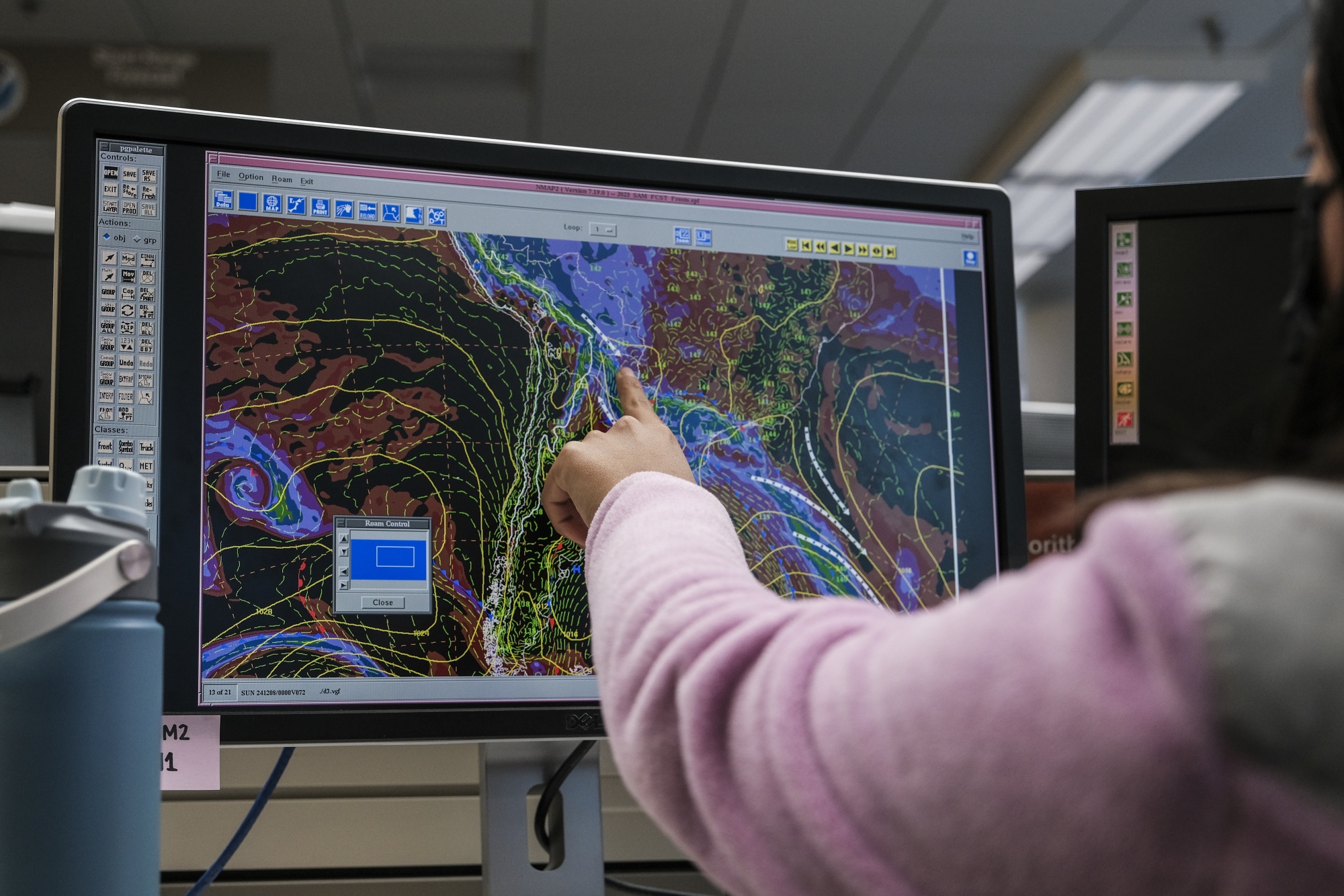

| By Eric Roston Tens of thousands of the world's top experts on hurricanes, drought, heat and volcanoes descended on New Orleans for a weeklong conference. A day into the meeting, they found themselves reeling over a disaster none of them saw coming: The Trump administration's plan to shutter one of the world's most significant climate research facilities. Doing so would be equivalent to pulling the engine out of a car hurtling down the highway, judging by scientists' reactions. Despite being under a cloud, though, attendees of the annual American Geophysical Union conference had work to do. After all, thousands of scheduled talks weren't going to give themselves. Over the week, five key themes emerged, showing how rapidly climate science is shifting in response to worsening weather, the Trump administration and the rapid rise of artificial intelligence. Here are the takeaways.  A meteorologist monitors weather activity. Photographer: Michael A. McCoy/Bloomberg Artificial IntelligenceMachine learning techniques have helped scientists translate their global models into regional impacts for at least 15 years. But advances in computing have further improved their ability to model the future — albeit still imperfect — including how society responds to disaster. University of Illinois researchers studying July's catastrophic floods in Texas found that large-language models they used to simulate officials' responses to weather warnings were "consistent with the real-world handling of this crisis." That can help improve decision-making in the face of the next flood. Meanwhile, a team at Brigham Young University is trying to train large-language models to translate a national river model into real-time, actionable consumer hydrological data. Their goal, professor Dan Ames said in a talk, is to turn a hard-to-access model "into conversations on your iPhone." GeoengineeringDimming the sun to cool the planet has long been a fringe idea. But this year's AGU featured dozens of talks and posters covering the once-taboo topic. The consensus: much more research is needed. Douglas MacMartin, a professor of engineering at Cornell University, walked his audience through some of the many tough questions about artificially lowering the temperature, including how to answer some of them with small-scale experiments. Other talks focused on the knock-on effects of putting cooling particles in the atmosphere, relying on volcanic eruptions as a stand-in for human intervention — a relatively new area of study with few answers so far. But areas where more research has been done have yielded some harrowing answers. If the world startsgeoengineering and then stops, it has the potential to double the impact of rising temperatures, according to Anthony Harding of the Georgia Institute of Technology. AdaptationThe arrival of climate change's impacts has added urgency to adaptation, and the geoscientists are on it. The diverse impacts of everything from heat to floods mean that all manner of researchers have a role to play in preparing communities living in at-risk areas. Winslow Hansen of the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, for example, shared findings that roughly 94 million acres of the US West are overdue for wildfire because of decades of fire-suppression policy. That type of information can allow fire agencies to use prescribed fire to thin forests most at risk and policymakers to implement rules to protect communities. AttributionScientists are pushing the boundaries of estimating the role greenhouse gas pollution plays in altering extreme weather. A talk on 2021's Hurricane Ida found that while the storm was once a one-in-8,000-year event, it's now a 2,000-year event and, thanks to continued greenhouse gas pollution, it has a 50% chance of happening again in the next 50 years. This type of forward-looking attribution can also be a tool for adaptation planners. NCAR's fateDisassembling NCAR is the latest assault on science by the Trump administration. Some researchers at AGU were ready to fight. About 7,000 people made calls between Wednesday night and Thursday afternoon, or sent letters to their members of Congress urging them to protect NCAR, said Antonio Busalacchi, the president of the consortium that runs the center. But some saw NCAR's dismantling as a reason to leave the US. Space physicist Alexandros Chasapis is planning to move back to France to continue his research. "The fact that this is on the table on its own is causing damage," he said of closing NCAR. "Even if they walk this back tomorrow, you lose trust." What was clear to countless researchers at AGU is the scientific value of NCAR. "Every scientist has benefited in some way from what NCAR does," said Marc Alessi, a science fellow at the nonprofit Union of Concerned Scientists. |

No comments:

Post a Comment