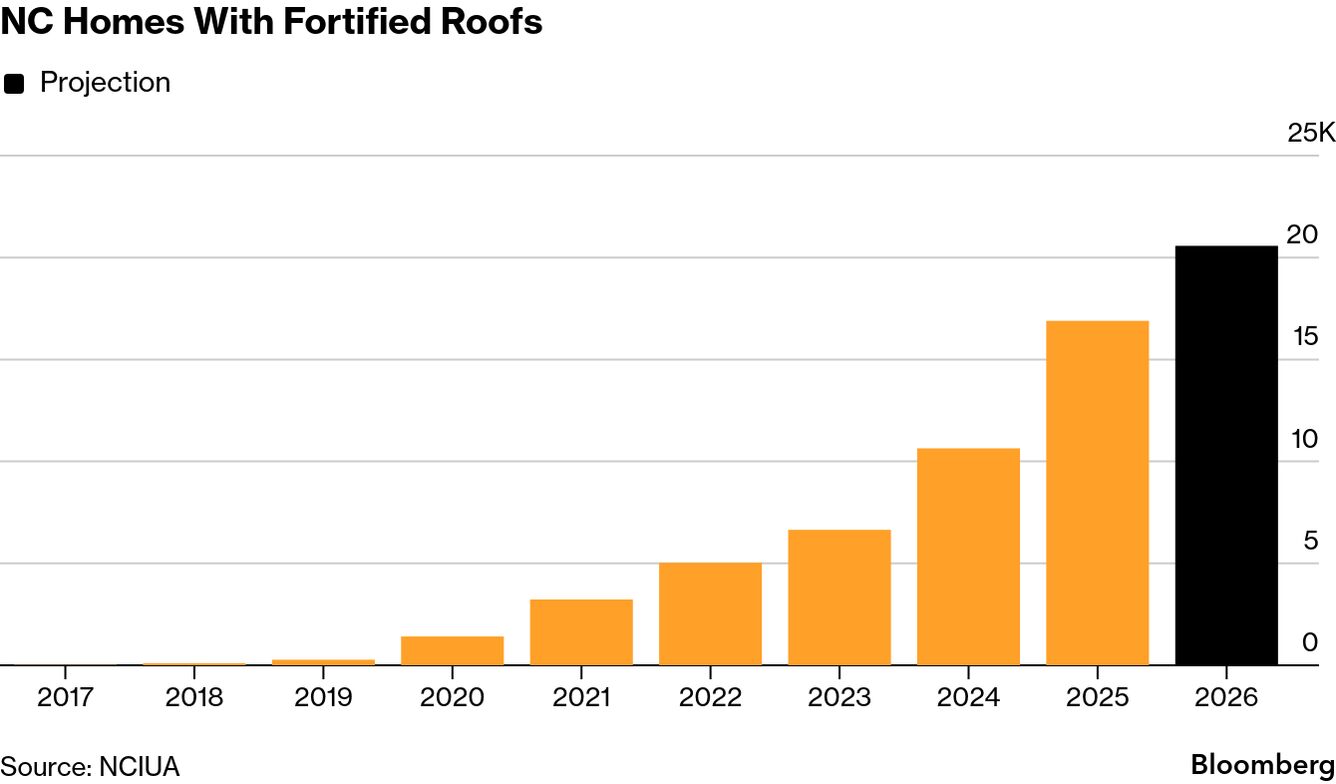

| By Leslie Kaufman As the Trump administration stalls federal funding for projects intended to make states more resilient to climate change and private insurers decline to cover properties in high-risk zones, North Carolina just proved there's another way to fund disaster preparedness: a $600 million catastrophe bond that rewards homeowners and their insurer for installing "super roofs." Along North Carolina's beaches, wind damage from hurricanes is such a threat that many private insurers have stopped offering coverage. Hundreds of thousands of homeowners have been forced to buy coverage from the North Carolina Insurance Underwriting Association (NCIUA), the state-created insurer of last resort for coastal properties. Like other insurers, NCIUA has to buy its own risk mitigation so it can pay customers if a major event causes more damage than it has saved from collecting and investing premiums. One option is reinsurance and another is a catastrophe bond, which pays out a specific amount if damage reaches a particularly severe level. Cat bonds have become popular with institutional investors like hedge funds and endowments in recent years because they trigger rarely and otherwise deliver high returns.  A home with a missing roof after Hurricane Dorian in Beaufort, North Carolina, in 2019. Photographer: Charles Mostoller/Bloomberg For years, academics and brokers have discussed whether cat bonds could do more than just clean up after disasters—whether they could incentivize mitigation work that would lessen damages in the first place. Earlier this year, NCIUA decided to test it: They offered investors a cat bond with two features linked to reducing wind damage risks to homes in its portfolio. First, if no major losses occur each year, $2 million returns to NCIUA—earmarked exclusively to incentivize homeowners to install "super roofs" that are especially wind-resistant. Second, as more people add these roofs, the annual pricing on the bond resets to reflect the changing exposure. It's modest financially but revolutionary conceptually, said Shalini Vajjhala, founder and executive director of PRE Collective, a San Diego-based nonprofit that works with communities and government agencies to clear barriers to building climate resilient infrastructure. "The North Carolina program is game changing," she said. "It's a precedent-setting way of linking how you manage your financial risks with how you manage physical risks." Super roofs prevented damage, but since they exceed building code requirements and cost roughly $3,400 more than a standard roof, few homeowners installed them. So in 2017, NCIUA began offering free super-roof replacements to homeowners who needed a new roof after a storm. They met resistance at first, said Gina Hardy, chief executive officer of the association. "With the free grants, people thought we were running some kind of scam." So the association engaged in consumer and contractor education. They also expanded incentives. In 2019, NCIUA offered $6,000 grants for super roofs during routine re-roofing, even though the upgrade cost just a fraction of that. They later increased it to $10,000. Homeowners essentially use the rest to defray regular roofing costs. It was those new grants that turned Marie Raynor, 59, from a skeptic to a buyer. She's lived in coastal North Carolina her entire life, and in 2024 her home in Wilmington, just a few miles from the beach, had a leaking roof. She received a mailing advertising the roof program, but worried it was an empty sales pitch; a call to the insurance office verified the program's veracity. Eight weeks after she applied, she had a new roof. And now she is "thrilled." It was one of the most painless renovations of her life, she says, and she is convinced that the new construction is venting wind and even heat in the summer. "I feel like it is also a rebate for all the years I paid insurance and didn't use it," she said. About two years ago, the program began really catching on. Today, more than 20,574 homes have these roofs or are in the process of adding them and more than 6,000 were added just this year. And the financial benefits are already accruing. After every storm, NCIUA checks the results. They've found that fortified homes had 60% fewer claims than code-compliant homes during regular storms, and 20% to 30% fewer claims with lower severity during named storms. Read the full story, including why the super roof success may be hard to replicate for other types of climate disasters. For access to all our coverage of how the insurance industry is evolving in a riskier climate, please subscribe to Bloomberg News. |

No comments:

Post a Comment