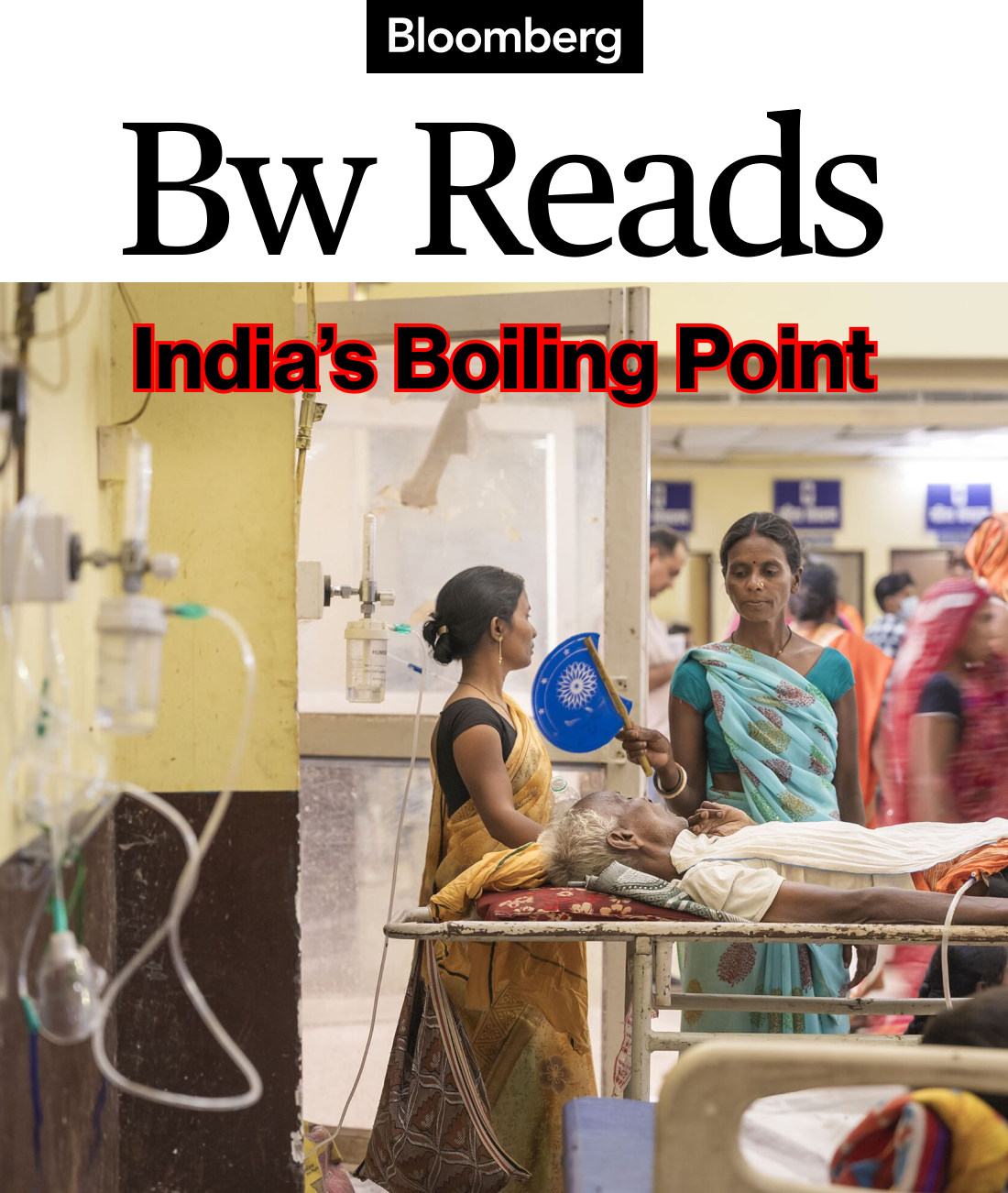

| Welcome to Bw Reads, our weekend newsletter featuring one great magazine story from Bloomberg Businessweek. Today, as Americans bid an unofficial farewell to summer with a holiday weekend, it's worth remembering that extreme heat will continue to be a problem in other areas of the globe. Rajesh Kumar Singh, Swati Gupta and Clara Ferreira Marques write about the terrifying and deadly reality in India. You can find the whole story online here. If you like what you see, tell your friends! Sign up here. When Gyanchand Saw climbed out of his car on a sweltering morning in mid-May, his son, sitting in the driver's seat, noticed beads of sweat trickling down the 55-year-old's forehead. Saw greeted a friend, exchanged a few words, then began to struggle. His body crumpled, and he fell to the ground. Panicked, Saw's son carried him back into the vehicle and began weaving through the traffic-clogged center of Gaya, a small city in eastern India, trying to find help. The family eventually brought him to the Anugrah Narayan Magadh Medical College & Hospital (ANMMCH), where the waiting area was already crowded with other patients and their families. On a stretcher, Saw lay still. A doctor ran over with a technician close behind, wheeling an electrocardiogram machine. After checking Saw's pulse, they connected the wires of the device to his chest and then watched as it printed the result on a roll of white paper: an unforgiving straight line. Breaking down in sobs around his body, Saw's kin tried to make sense of what had just occurred. A building contractor by trade, Saw had been on medication for a heart problem but was otherwise healthy, robust enough to spend his days working outdoors and traveling between jobs by motorcycle in all kinds of weather. Hospital staff said they couldn't provide a definitive cause of death until they'd conducted a postmortem. Sanjay Suman, the friend Saw was with when he collapsed, had no doubt what had happened: "From the moment he stepped out of the car," Suman said, "he was complaining about the heat. If it were not for this heat, he would still be here." As climate change transforms life in India, and much of the developing world, stories like Saw's are becoming more and more common. Ten out of the country's 15 hottest years on record were in the last decade and a half; in 2024, New Delhi experienced daytime temperatures higher than 40C (104F) for an entire month. With humidity, the air can feel as much as 10 degrees hotter. Even in a nation that's made huge strides in modernizing its economy, such temperatures can overwhelm railways and electrical grids, hampering exports and idling factories. They can also cause severe illness or death. And for hundreds of millions of Indians, the best option for help is to travel to somewhere like the ANMMCH. To understand the scale of the challenge, reporters for Bloomberg Businessweek made five visits to the government-run facility during the hottest time of the year: April, May and early June, before the monsoon rains bring relief. In many ways the low-rise building, which dates to the 1960s, is typical of medical centers across the country. Its wards are packed day and night with patients and their relatives, some of whom have traveled for hours in buses and rickshaws. The emergency room has no air conditioning, and its high, cobweb-covered windows are sealed, with the only cooling coming from slow-moving fans.  A patient in ANMMCH's general ward. Photographs by Kanishka Sonthalia/Bloomberg The most recent hot season was relatively moderate, with the daytime mercury in Gaya hovering around 35C, compared with a record-breaking 47C in 2024. The reporters nonetheless watched doctors and nurses treat a constant stream of patients for heat-linked ailments, from dehydration to heart complaints to breathing problems—a flow that intensified or slackened with the temperature. Inside it was only a few degrees cooler than on the street, and by midafternoon, moving around was physically taxing. Patients sat drenched in sweat, waiting to be seen by one of the two dozen medical staff working in the ER. With few chairs, many sat on the floor or on stretchers, their saline drips hung on nails or held aloft by family members. The toll of what researchers call "heat stress" is growing rapidly in India. Almost three-quarters of the workforce labors either outside or in indoor settings that have little to no cooling. Many are employed informally, and, in addition to the consequences for their health, those who collapse from heatstroke or dehydration forgo the income they need to survive. They also can't contribute to the growth of the economy. According to the International Labour Organization, heat stress will reduce India's annual productivity by the equivalent of 34 million full-time jobs by the end of the decade; the McKinsey Global Institute estimates that as much as 4.5% of the country's gross domestic product, or roughly $250 billion, could be at risk from such lost work. Although Prime Minister Narendra Modi's government has acknowledged that India needs a better strategy for dealing with heat, its concrete responses have so far been modest. There's no comprehensive national system for tracking deaths from heat, and only limited funds are available for long-term adaptation efforts, such as mapping urban areas that are at risk or planting trees to cool down those scorching cities. That leaves medical professionals in places such as ANMMCH working furiously to help their patients—overwhelmingly, laborers who don't have the luxury of taking time off when the temperature is dangerously high. If they stay outside long enough, they can find their brain function disrupted, causing dizziness and confusion. Internal organs can be deprived of blood and oxygen. Without prompt treatment, damage can be permanent. "There's not one system in the body that heat spares," says Kamlesh Kumar, the director of ANMMCH's heat-response department. "Right from the central nervous system—to our heart, to our muscles, kidneys and liver—everything is at risk." Keep reading: Heat Kills When Sweat Can't Evaporate. In India, It's a Deadly Reality |

No comments:

Post a Comment