| This is Bloomberg Opinion Today, a US asset that generates tens or even hundreds of billions of dollars of economic value for Bloomberg Opinion's opinions. On Sundays, we look at the major themes of the week past and how they will define the week ahead. Sign up for the daily newsletter here. "Looking back over a decade," wrote F. Scott Fitzgerald, an indifferent student if there ever was one, "one sees the ideal of a university become a myth, a vision, a meadow lark among the smoke stacks." I'm wondering what image the class of 2025 will see in 2035 as they look back on their remarkably tumultuous undergraduate years.

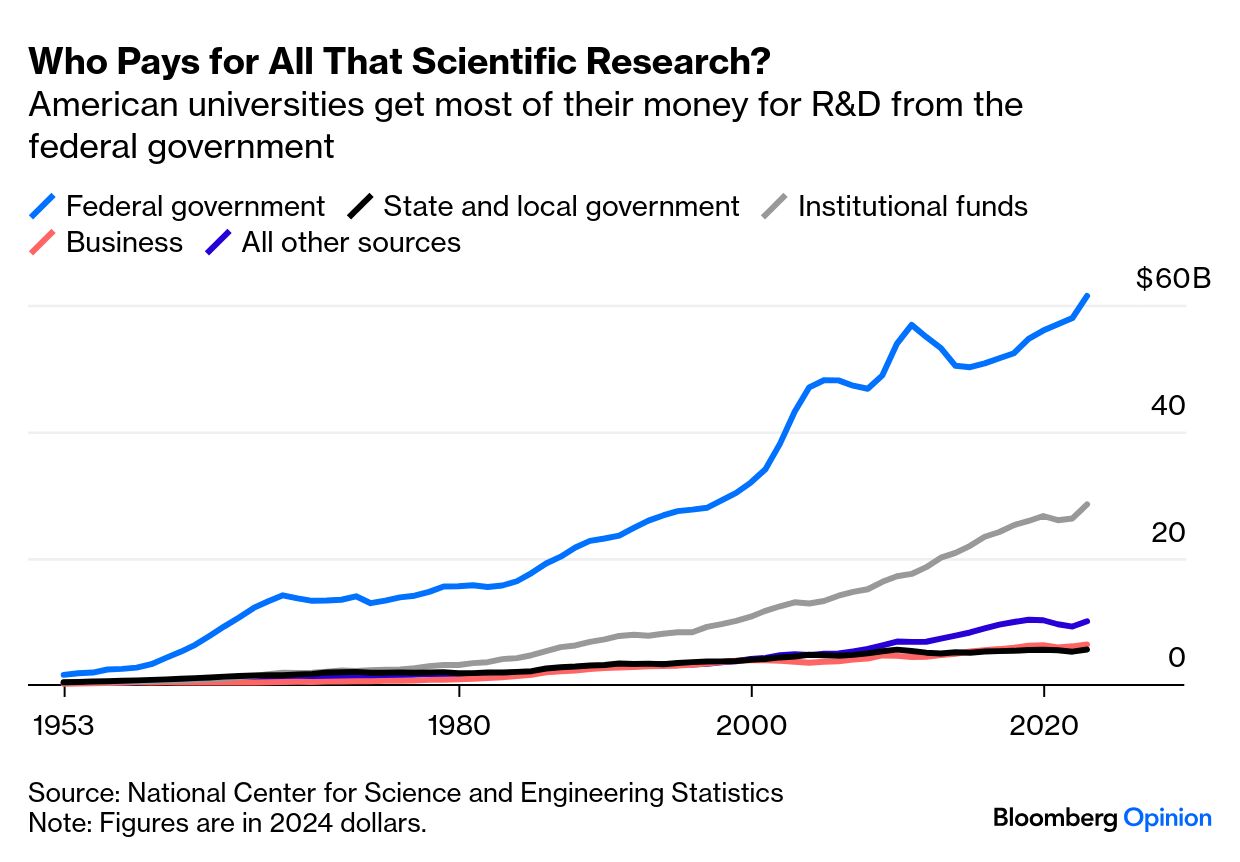

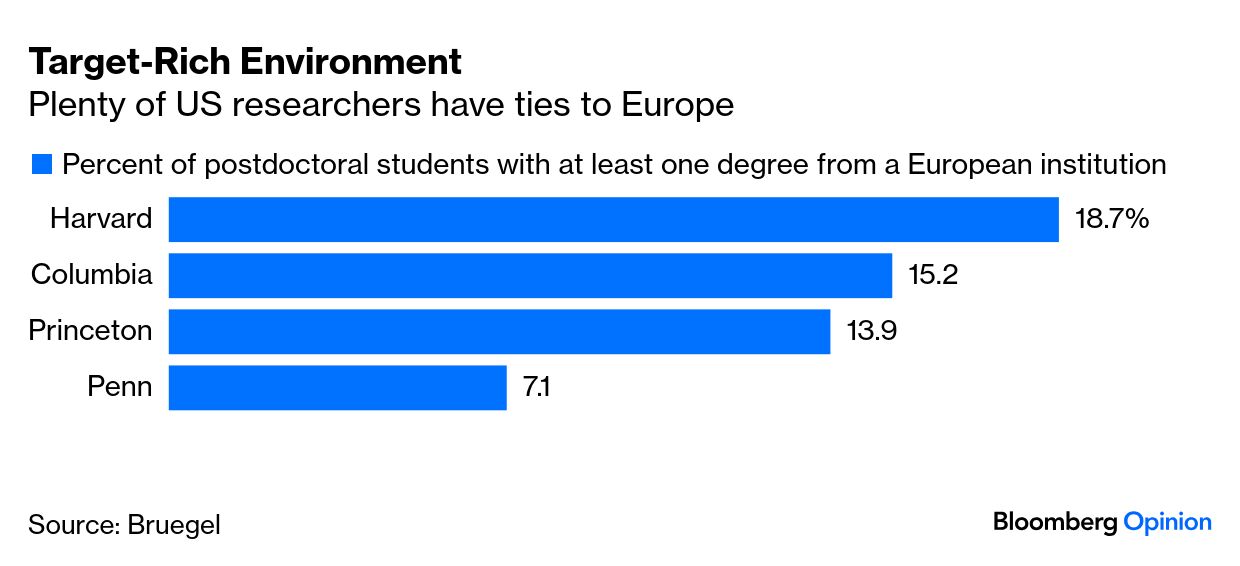

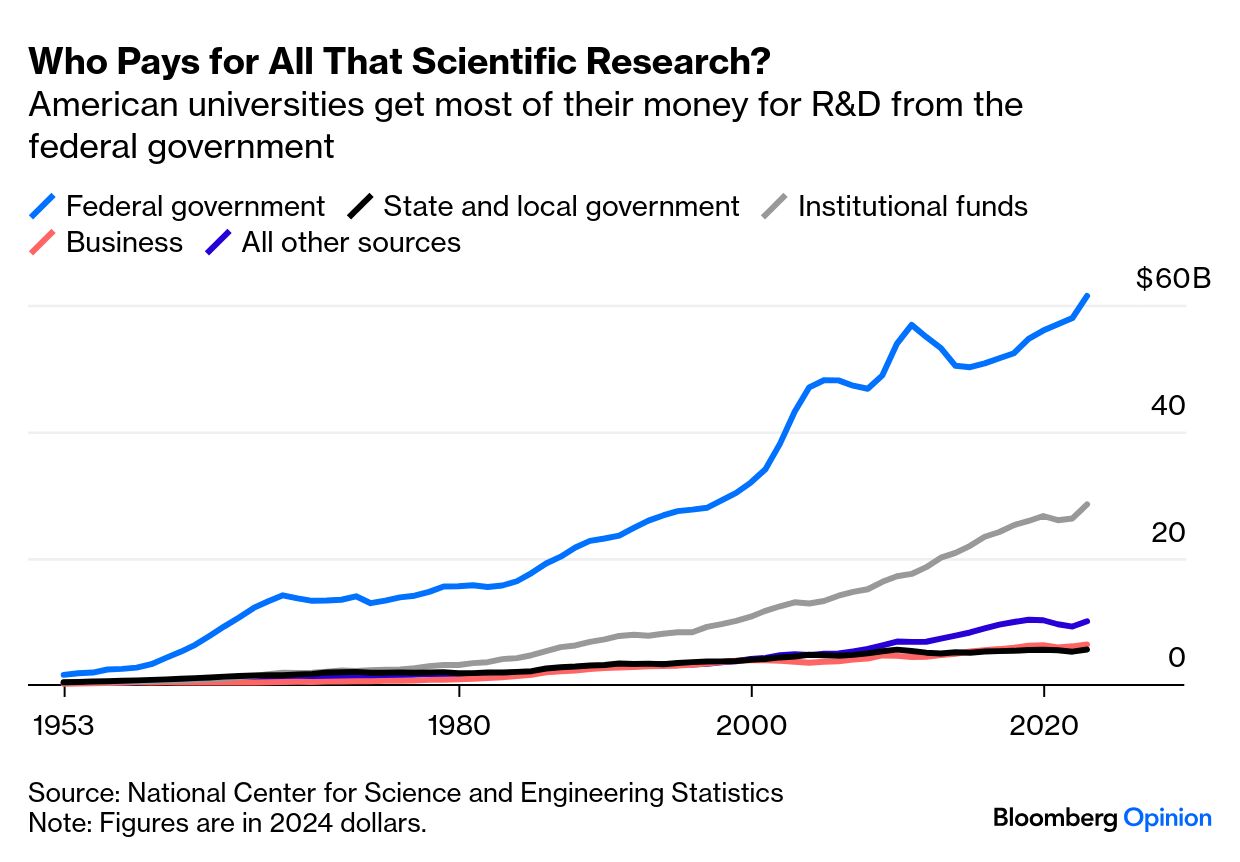

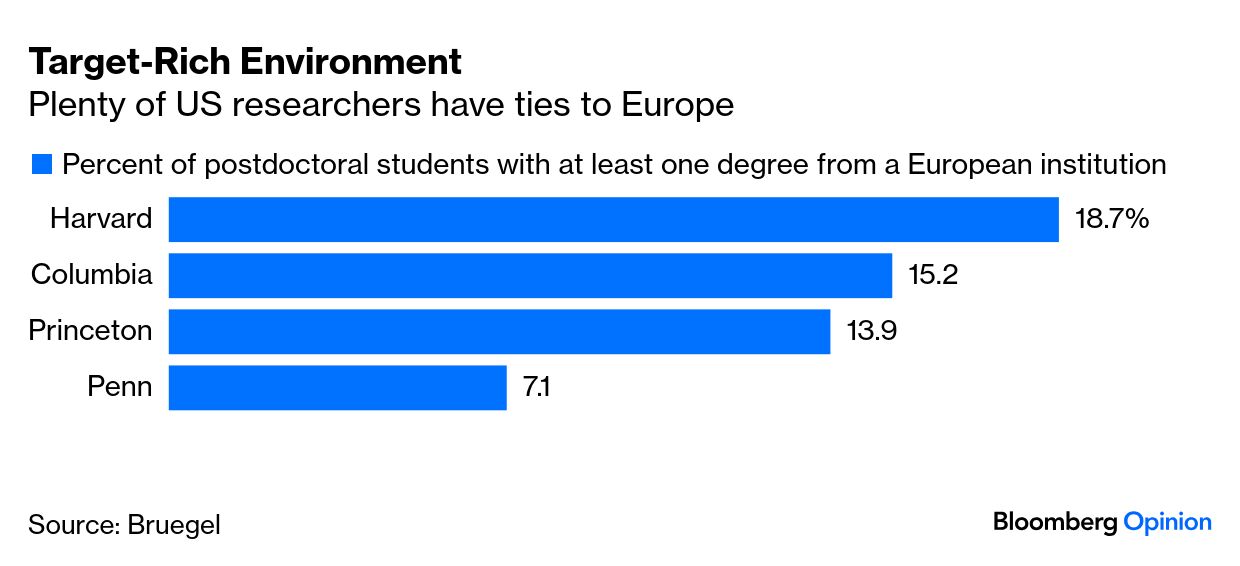

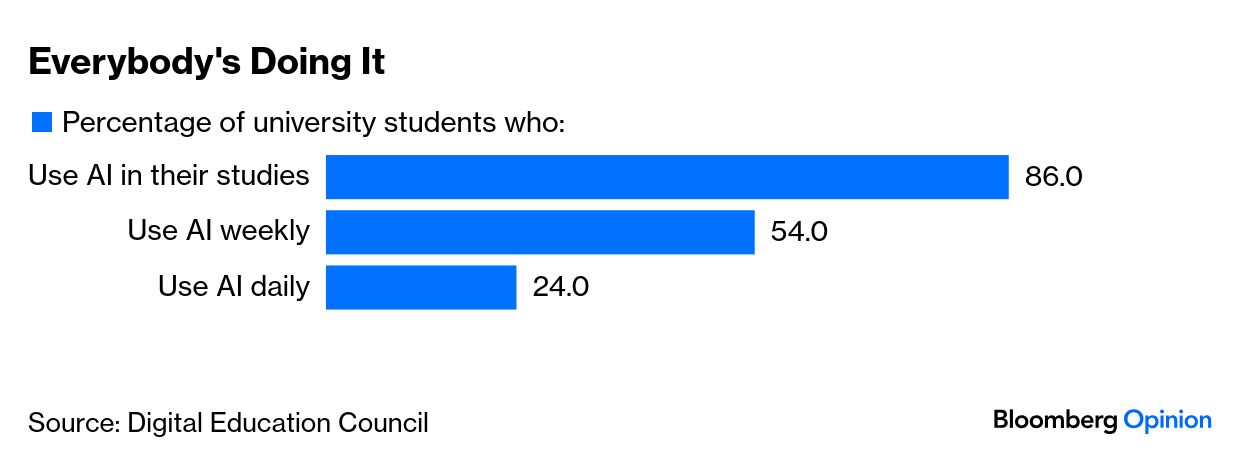

Will it be standing in defiance of administrators and politicians and police forces in a peaceful exercise of their First Amendment rights? Or standing in support of terrorists who murdered hundreds of people their age at a trance concert? Will it be the resignations of the presidents of Harvard, Penn and others under pressure from Congress and the White House? Or will it be those same leaders' failure to pass the relatively easy oral exam in Anti-Semitism 101 conducted by a congressional committee? [1] (Lesson here, kids: No matter how much you disdain your interlocutors, you might want to brush up on the course material the night before.) Will it be the arrogance of billionaire donors who are demanding big changes in the administration, curriculum and ethos at what are supposed to be impregnable citadels of higher learning? Or will it be the lesson that when you become dependent on the Bill Ackmans of the world, he who giveth can also taketh away? Will it be President Donald Trump's vengeful, outrageous and probably illegal efforts to deny grants and loans and take away the tax-exempt status of Harvard and other schools? Or will they see it all as payback for what my former colleague Niall Ferguson describes as "the willingness of trustees, donors, and alumni to tolerate the politicization of American universities by an illiberal coalition of 'woke' progressives, adherents of 'critical race theory,' and apologists for Islamist extremism"? Or, perhaps, they will they see May 29, 2025, as the moment we simply straightened everything out and were able to just move on. Noah Feldman, who was at Harvard's graduation last week, got that sort of vibe. "A year can make a transformational difference in the life of an institution," writes Noah (who admittedly has stake in things, being a tenured professor at Lex et Iustitia Law School). "That's what has happened at Harvard, where students and faculty gave President Alan Garber a standing ovation at commencement Thursday — just a year after protests disrupted graduation ceremonies when hundreds of students walked out. A year ago, student speakers denounced the university's administration and its trustees, who were sitting behind them. On Thursday, the speakers expressed pride in that same leadership for sticking to the university's principles and standing up for free inquiry and free expression." Gautam Mukunda, who teaches at rival Yale, thinks Trump's attack on Harvard is really an attack on America. "Imagine if China or Russia tried to destroy a US asset that generates tens or even hundreds of billions of dollars of economic value, plays a major role in American leadership in science and technology and turbocharges our prestige and soft power. We'd expect our government to go to war to defend it," he writes. "But in attacking Harvard University, that's exactly the kind of damage the Trump administration is trying to do. Despite the school's failures and flaws, it remains a vital national asset — and the administration's actions are far more dangerous to America than they are to Harvard."  If Allison Schrager had her way, however, a decade from now we would look back on maybe the greatest upheaval in higher education since the founding of the University of Bologna in 1088. "The current arrangement, apolitical graduate scientific research programs paired with highly political undergraduate arts and humanities departments, has become untenable," given the excesses of the latter, Allison writes. So how about a lesson in creative destruction? For her alma mater, Columbia, Allison suggests: "The engineering, medical and business schools, along with some of the hard sciences, could form one entity. The college, the humanities, and the social-science schools and departments could form another and continue with their activism." Whether Allison's proposed bifurcation is a glorious revolution or a reign of terror depends on your point of view (and whether you have tenure, I suppose). But would insulating the hard sciences from the liberal arts satisfy conservative critics? Consider Trump's latest initiative: blocking the enrollment of foreign students. "The repercussions promise to be devastating," writes the Editorial Board. "Projects in areas ranging from climate science to medicine have shut down. An exodus looms: Three-fourths of US-based scientists who responded to a recent Nature poll said they were seeking a way out, with Europe and Canada the top destinations. By one estimate, up to a fifth of postdoctoral students at elite US universities have studied in the European Union and hence might be amenable to moving."  It's not only the administration battering the elites: Congress is getting in on the act, proposing to raise the taxes paid on some university endowments from less than 2% to 21%. One of Matt Levine's clever readers, however, has a plan to get around it that makes Allison's creative destruction look like window dressing: Just become a for-profit company. "Under the tax proposal, a rich nonprofit university pays higher taxes than a for-profit company (because it pays taxes on all investment income, without being able to deduct operating expenses), so the big universities could become for-profit companies and pay lower taxes," explains Matt (a Harvard grad, natch). "This would cut off their main source of fundraising (tax-deductible donations), but would open up a huge new source of fundraising: selling stock. Obviously there is a problem with repurposing the existing huge endowments for for-profit purposes but, you know, if OpenAI can figure it out probably Harvard can." Which brings us to a distressing thought. Maybe the biggest problem universities face isn't addlebrained activism or disrespectful donors or a US president on a binge with a buzz saw. Maybe the real threat is the same one we, the parents of those students, face in our careers: technology. "For many college students these days, life is a breeze. Assignments that once demanded days of diligent research can be accomplished in minutes. … Welcome to academia in the age of artificial intelligence," writes the Editorial Board. "College kids have always cheated and always will. The point is to make it harder, impose consequences and — crucially — start shaping norms on campus for a new and very strange era. The future of the university may well depend on it." Let's end with that metaphor from my university's favorite son, Fitzgerald. [2] A decade hence, will today's graduates see a songbird in a meadow or a grimy gravestone of higher education? I suppose they'll just have to ask a chatbot. More Schooldays Reading: - America's Cold Shoulder to Foreign Students Is Worrying Asia — Karishma Vaswani

- Harvard Is Fighting for Much More Than Foreign Students — Noah Feldman

- Stop Scaring Future World Leaders Off US Campuses — Andreas Kluth

What's the World Got in Store ? - South Korea GDP, CPI, June 4: The Problem With Asia's 'Sell America' Moment — Daniel Moss

- ECB rate decision, June 5: ECB Should Keep Its Monetary Options Open This Summer — Marcus Ashworth

- US jobs report, June 6: The AI Job Suck Is the China Shock of Today — Jonathan Levin

One suspects that those university presidents who bombed in front of Congress might want a do-over. Too bad for them that "grading for equity" is the province of primary educators rather than the ivory tower. This progressive approach can allow students to retake tests repeatedly, and also exclude factors like lateness, participation and actually doing your homework from final grades. (It makes the "open school" fad of my youth look stringent.) But it is getting pushback from a perhaps surprising place: Democratic politicians. "San Francisco announced and then swiftly reversed a new 'grading for equity' initiative last week. The rapid reversal is a sign of a resurgent moderate wing of urban politics — and of a growing anxiety among Democrats that they are losing their traditional status as the party the public trusts on education," Matthew Yglesias (another Harvard grad, natch) reports. "The case for grading for equity, it should be noted, is more nuanced than a simple lowering of standards. But make no mistake: There are inescapable tradeoffs between the pursuit of excellence and a focus on purely egalitarian outcomes. There is also precious little evidence that faddish progressive ideas about equity actually improve things for students at the bottom." So, if we aren't going to give our kids get-out-of-class-free cards, how do we help them? In the best American tradition: with money! "The Republican tax bill contains flashy goodies for families with kids. The flashiest: savings accounts for children — branded Trump Accounts — created and initially funded by the Treasury Department. These will consist of $1,000 in invested assets for each American citizen born through 2028, plus whatever funds parents later add," writes guest contributor Abby McCloskey. On the face of it, this isn't a terrible idea. "As a country, we chronically underinvest in the young in favor of the old," adds Abby. "Parents are more pessimistic about their kids' future, according to Wall Street Journal polling, than any time in recent memory. The US is an international outlier with its high share of single parents. Labor policy still doesn't reflect the reality that in most households, all parents are working. But there are better ways to promote familial financial well-being than Trump Accounts." Like, say, giving our children a useful education?  Source: Tenor Notes: Please send loaded Trump Accounts and feedback to Tobin Harshaw at tharshaw@bloomberg.net. |

No comments:

Post a Comment