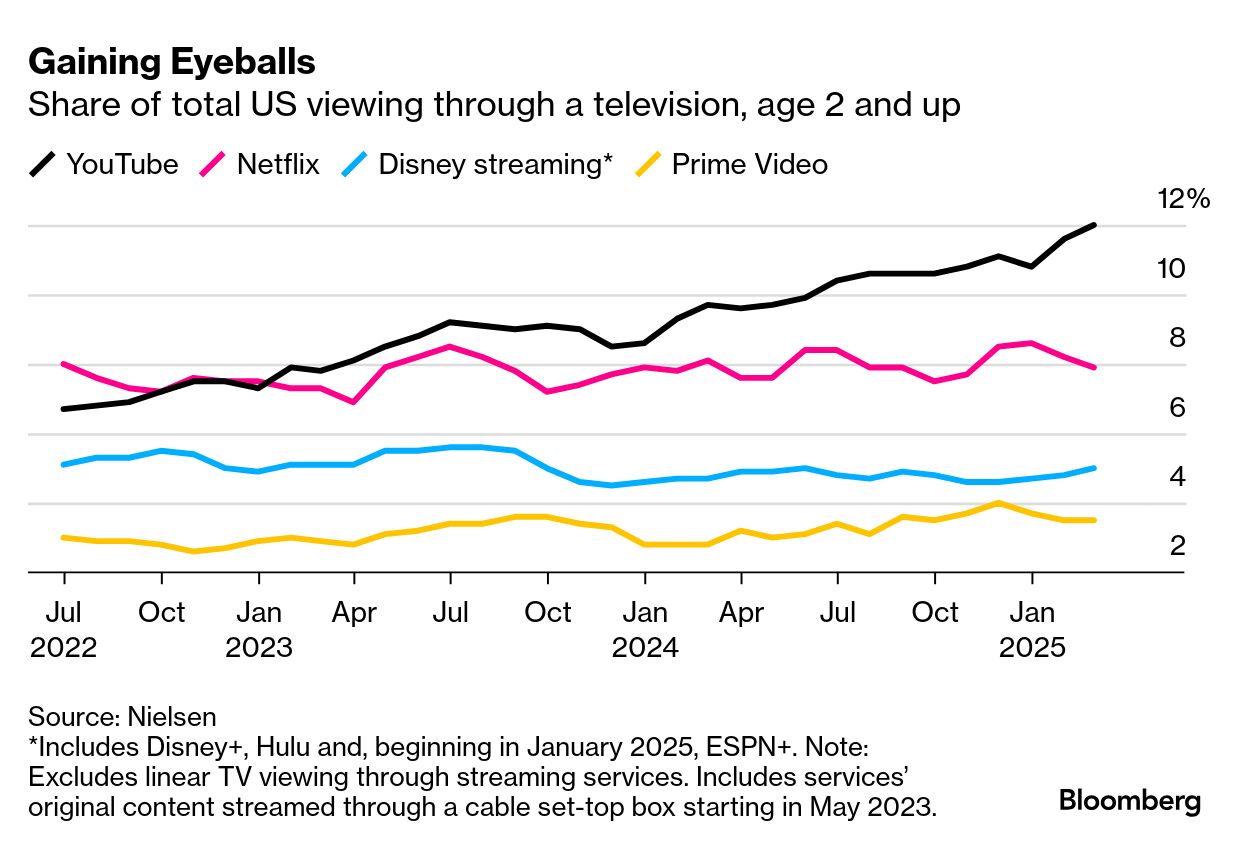

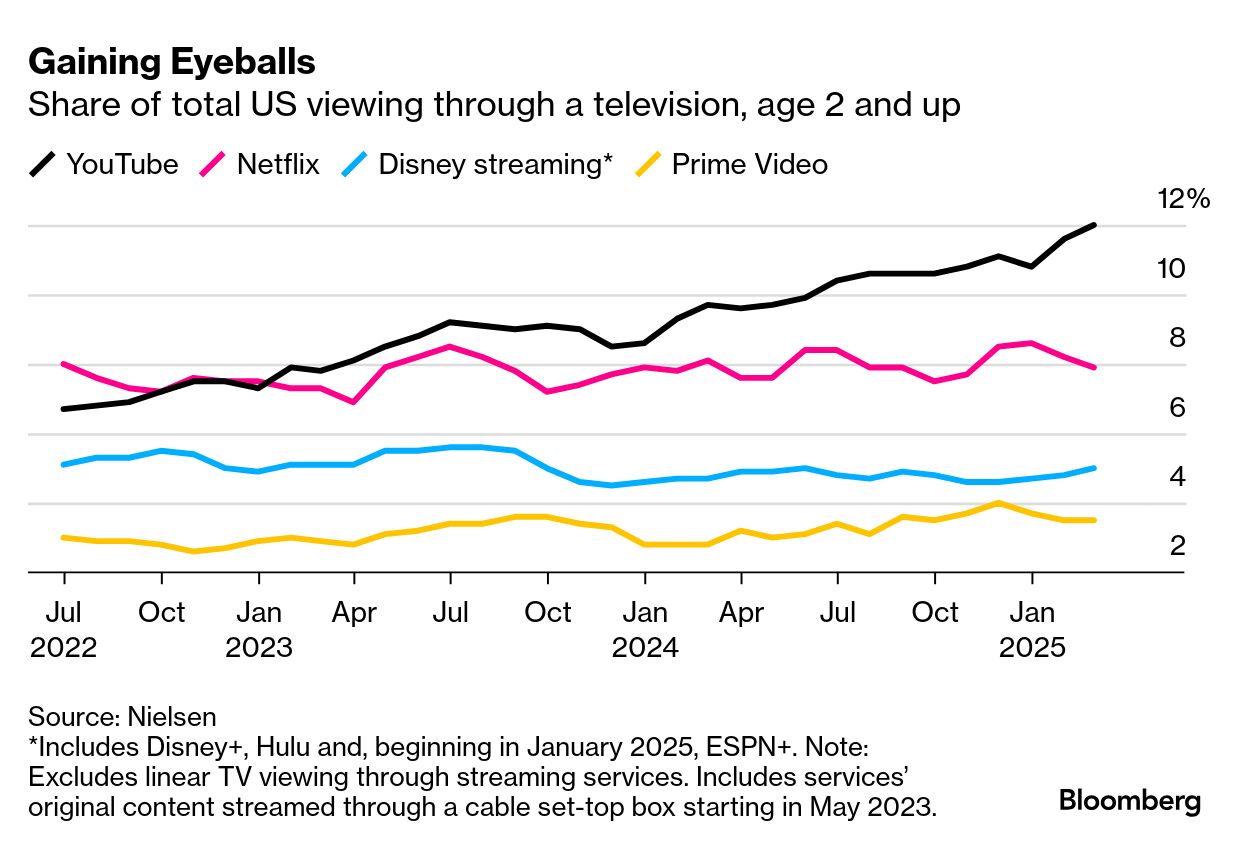

| Welcome to Bw Reads, our weekend newsletter featuring one great magazine story from Bloomberg Businessweek. Today, Lucas Shaw explains how YouTube has spent the past few years trying to make itself the centerpiece of the living room, and why Hollywood studios see that as a threat. You can find the whole story online here. If you like what you see, tell your friends! Sign up here. For two decades, YouTube has tried to convince advertisers that it's the future of entertainment. The pitch has always been simple enough: "Young people don't watch cable; they watch YouTube." It doesn't exactly require a PowerPoint presentation. But YouTube has had problems making its case. The first is that the vast majority of videos on the site aren't filmed to Scorsese-like standards. "The biggest knock against creator content is that it's low quality, s---, crap, slop, garbage," Doug Shapiro, a former executive at Time Warner, wrote in December. That's sort of inconsequential, he argued, since most people aren't watching random YouTube slop—they're watching the most popular slop. Which leads to YouTube's second issue: The most watched channels haven't always been hospitable to advertisers. To name a few high-profile examples: Felix Kjellberg, aka PewDiePie, a Swedish YouTuber known for his gaming content, made antisemitic jokes in videos in 2016 and 2017 and was later accused of inspiring White nationalist shooting rampages. Logan Paul, who posted gaming and prank videos before ascending to influencer-wrestler status, filmed a video in 2017 with a dead body in a Japanese suicide forest. In 2020, Jason Ethier, aka JayStation, a Canadian YouTuber known for videos such as "Running From the Cops" and "24 Hour Overnight Challenge in Jail," tried to gain followers by pretending his girlfriend and fellow YouTuber Alexia Marano had been killed by a drunk driver. Marketers don't have to worry about this kind of stuff on, say, NBC. (All three creators apologized, and YouTube ultimately took down that JayStation channel for violating its terms of service. In a video, Marano said she never agreed to the hoax and was "sick to her stomach" about it.) To attract those advertising dollars, YouTube set about trying to boost the quality of videos on the site. In 2011 it announced plans to invest $100 million in original programming. The funds went to dozens of channels from popular creators such as Philip DeFranco, a pop culture commentator who currently has more than 6.6 million followers, and Felicia Day, an actress best known for the web series The Guild, which was based on her life as a gamer. Four years later, YouTube backed a smaller number of prestige shows to drive viewers to YouTube Red, an ill-fated attempt to compete with Netflix Inc. in subscription video. The company hired Susanne Daniels, a longtime Hollywood executive who'd developed Dawson's Creek and Buffy the Vampire Slayer, to oversee the slate, which included Cobra Kai, which takes place about 30 years after The Karate Kid saga. And beginning in 2017, YouTube started funding dozens of ad-supported original series that it offered for free, such as Kevin Hart: What the Fit, in which the comedian works out with celebrities including Conan O'Brien, DJ Khaled and Rebel Wilson. Not much found a huge audience. Daniels' biggest discovery was a young writer named Quinta Brunson, who created Broke, a comedy about three friends who move from Philadelphia to Los Angeles. The show lasted just one season, but Brunson went on to create Abbott Elementary, a hit for ABC. YouTube gradually wound down its originals efforts and allowed Sony Group Corp.'s TV studio, which produced and owned Cobra Kai, to shop the rights to future seasons. The show became a huge hit for Netflix. Daniels left in 2022. YouTube had more success cleaning up its existing catalog, promoting stars it prayed wouldn't do dumb stuff. It built tools to monitor the site for things such as Japanese suicide forests—and ran marketing campaigns to boost the cultural relevance of major creators, hoping that billboards of Liza Koshy, an actress from Houston, or Smosh, a sketch comedy-improv collective, would make advertisers think of them as movie stars. New programs let companies target ads to the top 1% of videos by viewership. YouTube channels such as MrBeast; Good Mythical Morning ("Coworkers Reveal Their Search History to Each Other"); and First We Feast, the home of wing-eating talk show phenomenon Hot Ones, grew so popular that even if some advertisers didn't see the service as premium, most viewers didn't care. The site became "too dominant not to be a major part of advertisers' media plans and their video strategy," says David Campanelli, president, global investment at Horizon Media Inc., which buys a lot of YouTube ads. Even as advertisers spent more money on YouTube, executives at parent company Google thought it should be securing ads from marquee brands, whose large checks were instead going to TV networks. YouTube still made most of its money from low-cost commercials targeted at niche audiences. And many advertisers still thought their commercials didn't have the same impact when they appeared next to YouTube's cheaper, shorter videos, most of which were viewed on phones or laptops.  YouTube has spent the past few years trying to make itself the centerpiece of the living room. The company teamed up with TV manufacturers so watching YouTube on a TV became as easy as watching it on your phone or laptop. People can now leave comments and subscribe to YouTube channels on a TV, and creators can arrange videos as though they're episodes of a show. YouTube will remind viewers where they left off with a program and feed them the next episode—rather than have the algorithm offer a similar video, often from another creator. YouTube also tailored its advertising for TV viewing, creating more space between ad breaks. The company introduced pause ads, which show commercials when a viewer stops a video, and it introduced a live-TV service, YouTube TV, that includes the channels in a cable bundle—crucially, the ones that show the NFL—as well as a storefront that offers paid streaming services such as Max and Paramount+. YouTube is now the TV service of choice for viewers of all ages. People in the US spend more time watching YouTube on a TV than on a phone or computer, according to the company. Not including YouTube TV, the service accounted for over 12% of TV viewing in April, more than all of Walt Disney Co.'s TV networks and streaming services combined, according to Nielsen. About 40% of viewers are age 18 to 49, the demographic most appealing to advertisers, Nielsen reported. "When people turn on the TV, they turn on YouTube," says YouTube Chief Executive Officer Neal Mohan. While linear TV ad sales have flatlined, YouTube has more than doubled its ad sales over the last five years, from $15 billion in 2019 to $36 billion in 2024, according to earnings reports. YouTube now generates more sales from advertising than all four broadcast networks combined. Hollywood executives still try to portray YouTube as a slopfest. In a recent public appearance, Netflix co-Chief Executive Officer Ted Sarandos said YouTube is a place people kill time, whereas his service is a place where people spend time. But these comments now reek more of fear than confidence. As much as Hollywood has worried about labor strife, artificial intelligence and the demise of moviegoing, the rise of YouTube is a much more immediate and real threat. Keep reading: YouTube Is Swallowing TV Whole, and It's Coming for the Sitcom |

No comments:

Post a Comment