| There's a packed agenda, but this week the topic of the Federal Reserve, its independence, its current policy, and whether the president has the right to fire its chairman swamps all else. That's because of remarks Jerome Powell made Wednesday to the Economics Club of Chicago: Our obligation is to keep longer-term inflation expectations well-anchored and to make certain that a one-time increase in the price level does not become an ongoing inflation problem. We may find ourselves in the challenging scenario in which our dual-mandate goals are in tension.

In other words, the one-off rise in the price level caused by tariffs might raise both inflation and unemployment and require the Fed to hike rates. That provoked this Truth Social post from the president: Mr. Trump then said this to reporters on Thursday: I'm not happy with him. I let him know it. And oh, if I want him out, he'll be out of there real fast, believe me.

And on Friday he said this: If we had a Fed chairman that understood what he was doing, interest rates would be coming down. He should bring them down.

Over the weekend, presidential economic adviser Kevin Hassett confirmed that the administration was considering ways to fire Powell, and complained that the Fed hadn't made similar complaints on TV over the "obvious runaway spending from Joe Biden [that] was textbook inflationary." Powell wasn't in charge when Trump first took over (and of course Trump then chose him to succeed Janet Yellen), but it's clear that the administration regards the Fed as a partisan opponent more than an independent institution. There's clear intent to force a confrontation over Powell's job in the short term, and over the Fed's status in the only slightly longer term. Here are some attempts at answers to the most important questions that arise: Can the Administration Do This? A president can fire a Fed chairman but only "for cause"; nothing about independence protects him or her from accountability for fiddling expenses or insider trading. In 2021, the Dallas Fed President Robert Kaplan and Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren, both highly respected, resigned after the revelation of big stock transactions during the Covid disruption in 2020. (They were subsequently exonerated of misconduct but criticized for damaging confidence in the Fed.)  The longer-term target is the Fed itself. Photographer: Samuel Corum/Bloomberg The problem for Trump is that Powell's own financial dealings have been above reproach. As an independently wealthy man long before the job, this isn't surprising. A laughable attempt to pin insider trading on him in 2021 went nowhere. So firing Powell will require either a change in the law governing the Fed's relationship to the executive, or a big stretch of the concept of "cause." The first might just come from the Supreme Court, as explained for Bloomberg Opinion by Kathryn Judge and Lev Menand, depending on how it rules on the administration's attempts to fire heads of two other federal agencies. There is also an argument, made by Jay Hatfield of Infrastructure Capital Advisors, that Powell can be dismissed for cause. He says: The term "for cause" is used in legal settings to indicate that a decision or action is based on a valid, justifiable reason, rather than being arbitrary or without basis… In the case of Chair Powell, the President clearly has a case to fire him for cause. As Fed Chair, Powell developed the "Transitory" theory of inflation after advocating for higher government spending, which together precipitated the Great Inflation of '21.

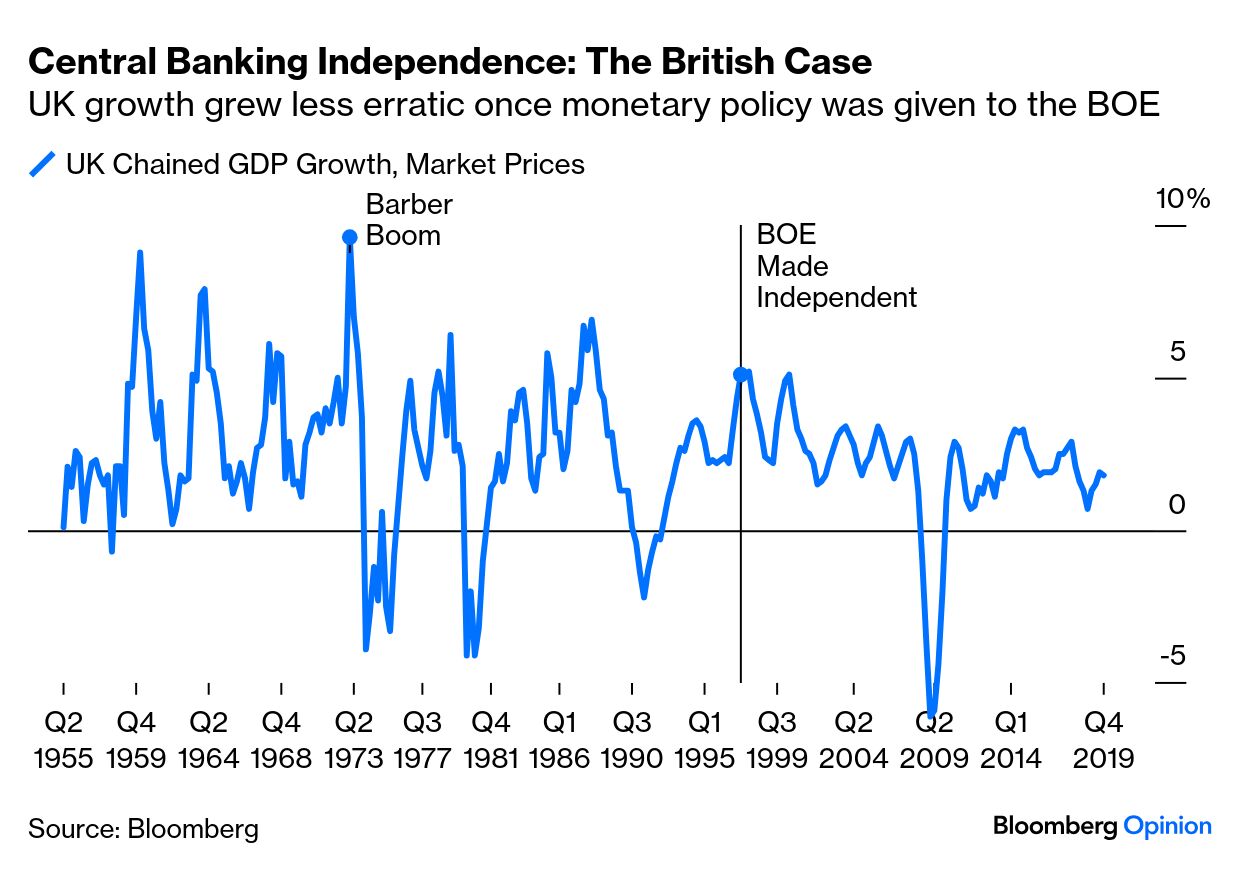

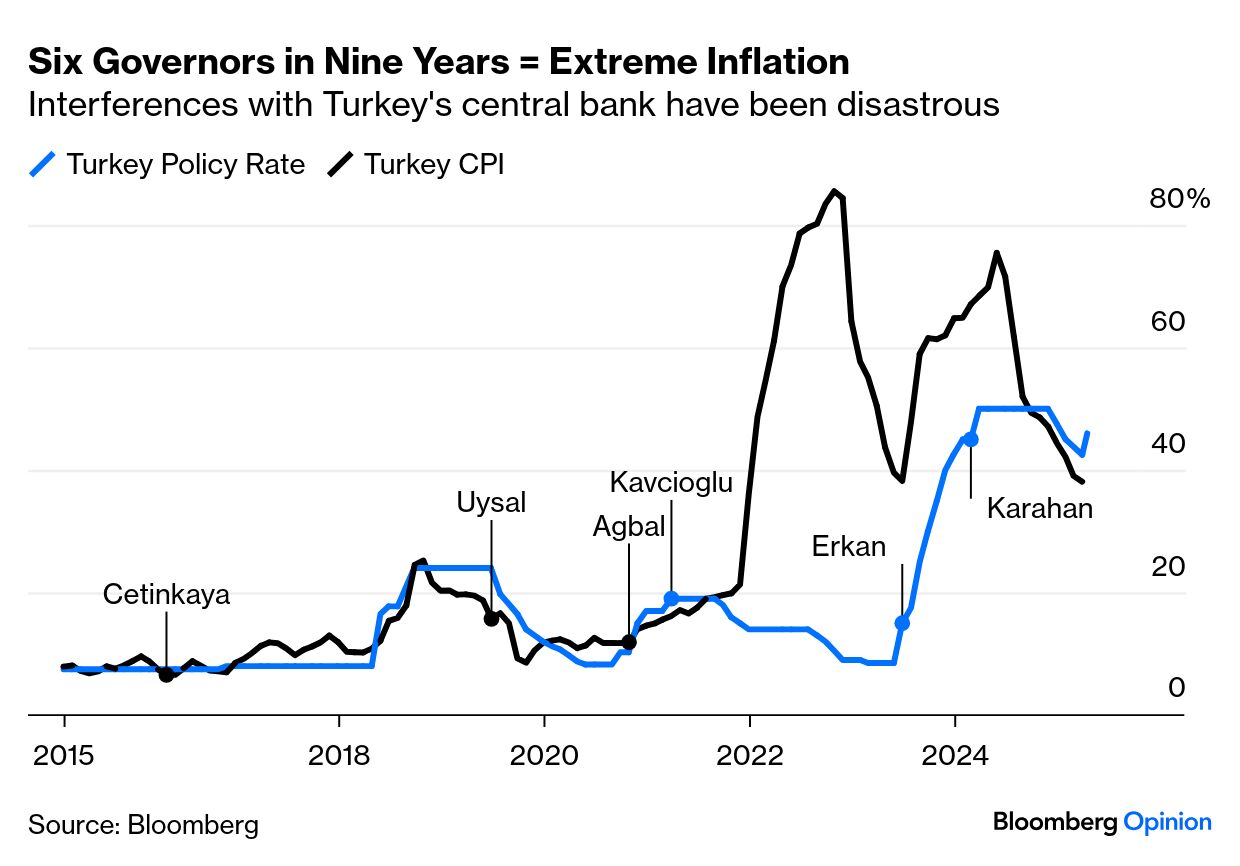

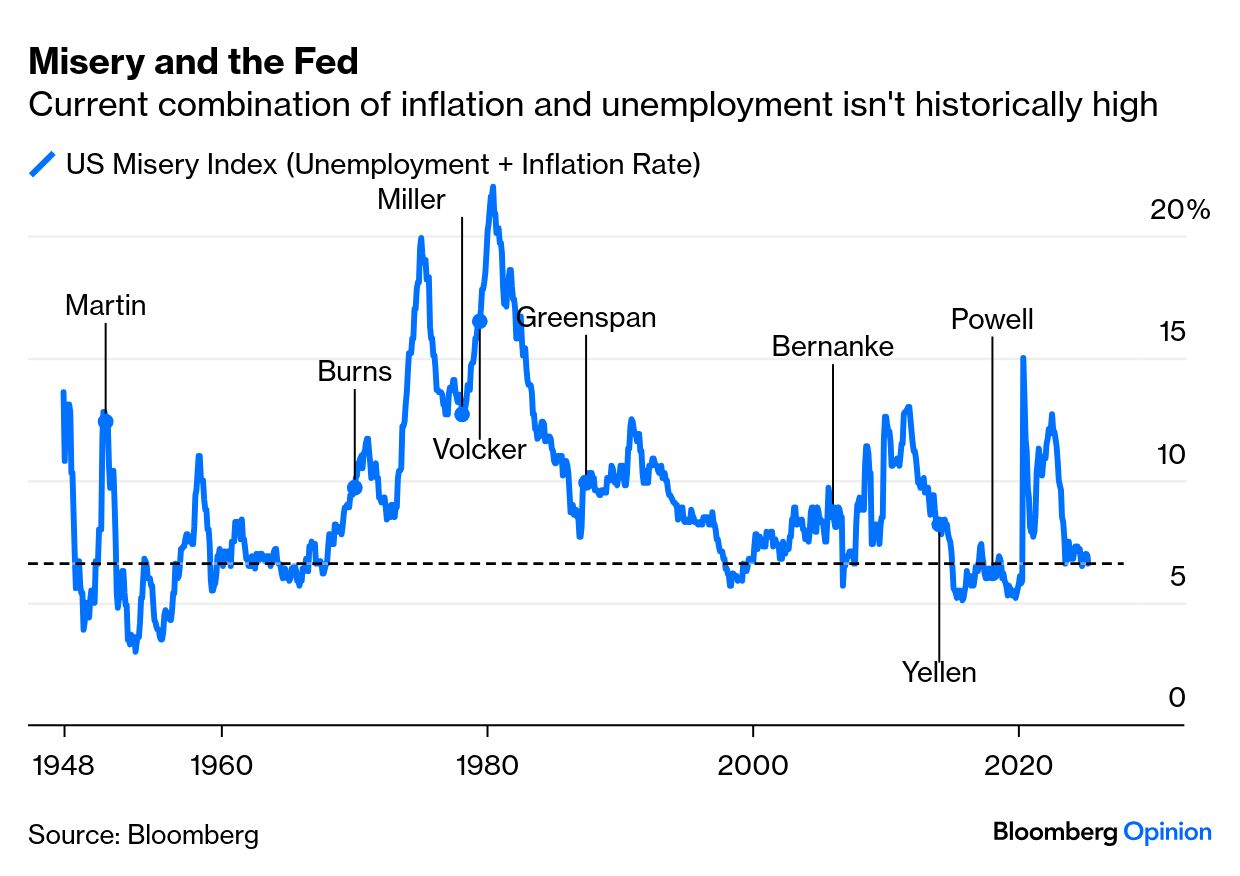

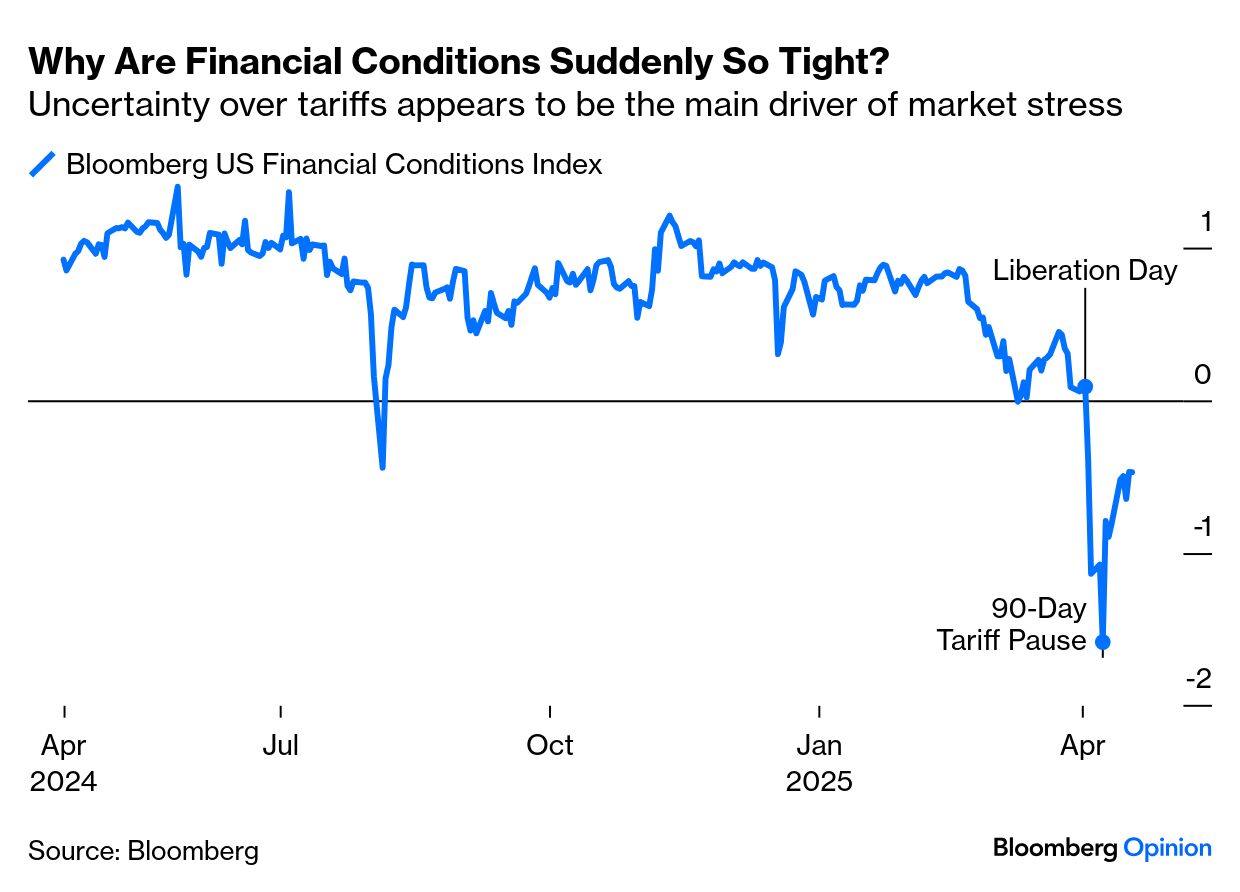

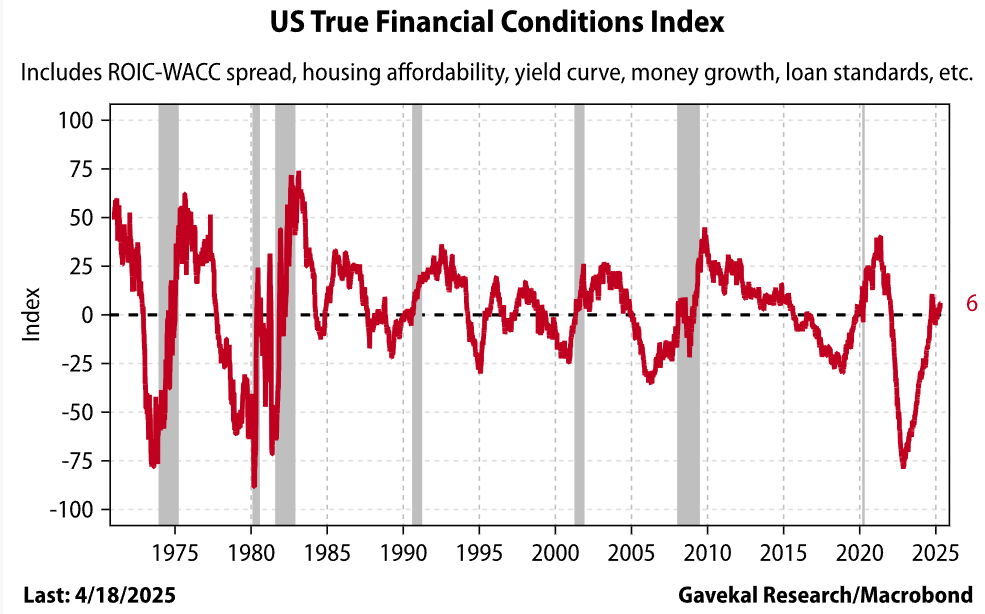

This argument is contentious, but establishes that if the administration wants to do this, it can, and fight with the courts later — a modus operandi that it has used several times already. It's not an empty threat. Should Central Banks Be Independent? The answer isn't obvious. Central bankers are hugely powerful and not subject to regular democratic limits. That's problematic. Most central bankers get appointed via the democratic process but face minimal oversight thereafter. And independence isn't eternal. The Bank of England's interest rates were set by the (elected) chancellor of the exchequer until as recently as 1997.  Alexander Hamilton was controversial, too. Source: Universal History Archive/UIG/Getty The issue has recurred throughout US history, starting with Alexander Hamilton. Central bankers are aware of their lack of democratic legitimacy; it led for example to Ben Bernanke's insistence that Congress authorize the TARP bank bailout during the 2008 crisis. Sir Paul Tucker produced a huge tome called Unelected Power once he'd stood down as the BOE's deputy governor, setting out the arguments for altering oversight of central banks and other quasi-autonomous entities. In practical terms, the case for keeping monetary and fiscal decisions separate is hard to rebut. Generally, governments want to make life easier in the present, which means a temptation to lower rates too much; they're naturally more reluctant than an independent central banker to remove the punch bowl as the party gets started. Controlled experiments are difficult in economics, but the UK and Turkey give an idea of the difference in outcomes when governments interfere in monetary policy. In the UK, Tony Blair gave the BOE independence in 1997. Until then, a chancellor could coordinate rates with fiscal stimulus, creating what was known as "stop-go economics," with booms before elections, followed by painful slowdowns. UK GDP growth before and after the BOE started setting rates suggests that independence makes for a smoother and more consistent ride: (On a historical note, the most extreme example of Stop-Go came in the "Barber Boom" driven by the Conservative Chancellor Anthony Barber in the early 1970s. Its disastrous consequences were a critical factor in persuading the party to take on the free-market Margaret Thatcher as its next leader.) More recently, Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has cycled through six new central bank governors since 2016, and in 2021 forced the application of his novel economic theory that to combat inflation it was necessary to cut rates, not increase them. Here are the results: Independent central banks have made terrible, avoidable errors in recent history, generally by being too enthusiastic to cut rates — which is what Trump wants the Fed to do. History suggests that ceding this power to elected politicians would make things even worse. There is a natural tension in economic policy between fiscal and monetary measures, and between trying to maximize employment and minimize inflation. It makes sense to institutionalize that tension with an autonomous central bank. Does Powell Really Deserve to Be Fired? If economic outcomes can really be "cause" for dismissal, they need to be really bad. The hideous policy error of 2021, when the Fed continued with QE and zero rates amid rising inflation, is the obvious candidate. That was unquestionably a bad mistake in hindsight, although plenty defended it in real time. The unprecedented conditions of the pandemic made policy-setting difficult. But how bad was it? Since Jimmy Carter, the shorthand for combining the Fed's two mandates has been the Misery Index — the unemployment rate plus the inflation rate. That currently stands at 6.6%. Historically, that's pretty good. Why fire the guy now? Trump's argument that Powell is "too late" and should be cutting rates further also has plenty to recommend it; many reputable economists agree, and few would dismiss it out of hand. But it's hard to argue that financial conditions are unduly restrictive at present, or that monetary policy is harmful. Bloomberg's US financial conditions index, which smooshes together indicators from cash, bond and equity markets to gauge risk appetite, has indeed tightened of late (any number below zero denotes restrictive conditions). Why? The circumstantial evidence points to tariffs, not monetary policy that has been unchanged since the last rate cut in December: Will Denyer of Gavekal Economics argues that indexes like this gauge risk appetite, not the "true" conditions that foster credit growth. The following index captures it by combining money supply growth, the yield curve, metrics of vitality in the banking sector, the spread between the rate of return on corporate investments in real assets and the real cost of financing those investments, and measures of housing affordability. It showed terribly tight conditions as the Fed belatedly took on inflation in 2022 — and a normal, slightly loose environment now: The Fed stayed too easy for too long in 2021. But why punish Powell now? At this point, the economy is almost near Goldilocks conditions, and the Fed has dealt with the worst inflation outbreak in decades without causing a recession. Then there is the issue of what impact the firing in itself might have. What Happens If He's Indeed Let Go? There are plenty of ways the Fed's current constitutional position might be improved, but this doesn't affect whether Powell should be fired now. He shouldn't. It would virtually ensure a market disaster. Why? For all the criticism it deserves, the Fed is consistent and markets generally know where they are with it. Its institutional stability is one of the cornerstones of the US financial system, and by extension, given the dollar's reserve status, of world finance (which explains why foreign governments don't want Powell to go). If the president does this, responsibility for rates will move to him. Will the market transfer its trust in the current Fed to a new regime headed by Donald Trump?  Markets won't like it. Photographer: Will Oliver/EPA Headlines from the last few weeks should answer that. Recently: - The administration sent a letter threatening to pull all federal funding from Harvard by mistake.

- "Reciprocal" tariffs on most of the world were delayed for 90 days after the Treasury and Commerce secretaries heard the president's trade adviser was busy in another part of the building, and persuaded him to announce the delay on social media.

- A man was deported to El Salvador despite a court order barring the government from doing so.

- The government conceded he'd been deported by mistake but said that the US (GDP: $28 trillion) couldn't persuade El Salvador (GDP: $34 billion) to return him.

- The new head of the Internal Revenue Service, responsible for Uncle Sam's Accounts Receivable, was replaced after three days due to a power struggle.

- A group including the Defense secretary and the national security advisor inadvertently shared their plans for a missile attack on Yemen with a journalist.

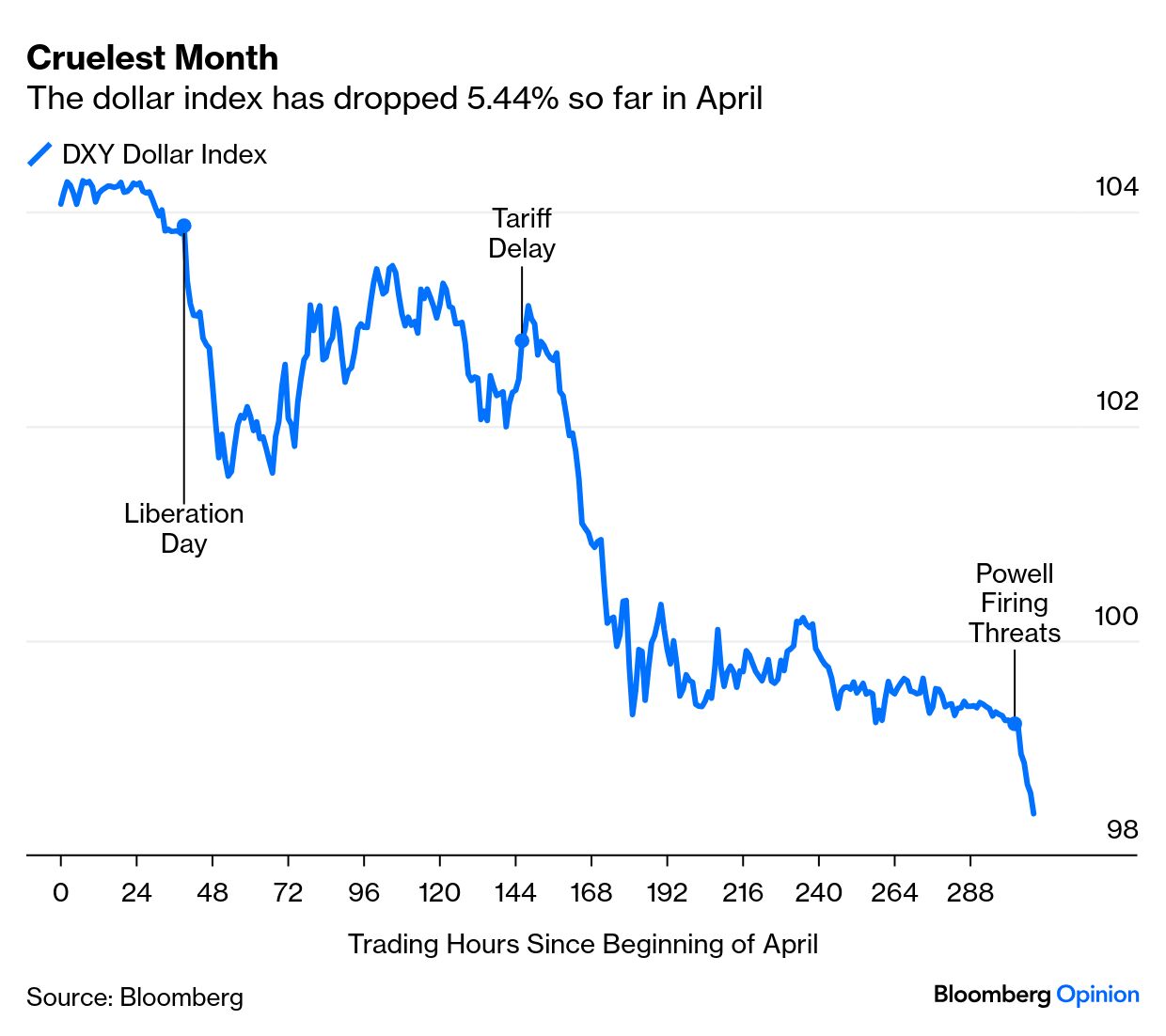

This is Keystone Kops stuff. The Fed has many issues, but nobody will trust the people behind this catalogue of errors to handle a drastic move to bring it to heel. Trust in the dollar has been shaken in recent weeks. It's not yet broken. In this febrile setting, firing Powell might finish the job — the mere threat of it was enough to force another leg down for the greenback in early Monday trading: What Might Trump Do Instead? Powell's term ends early next year. There is an obvious candidate to replace him in Kevin Warsh, an investment banker and a key Fed governor during the Global Financial Crisis. He would have the general trust of markets while also being philosophically attuned to Trump. It probably helps that he's married to the daughter of one of Trump's best friends. Many on Wall Street already talk of a Warsh chairmanship as a fait accompli — but starting next year, not now. If the White House is serious about finding a better way to balance the Fed's needs for independence and democratic accountability, it has 12 months to consult, and majorities in Congress to make changes. That is a clear and responsible course of action to make significant reforms with a minimum of market upset. If, as it appears, this is more of a personal vendetta, the administration could instead provoke an epic financial crisis by firing Powell now. Most of us would prefer it didn't. |

No comments:

Post a Comment