| Checks and balances look better now. So does the Deep State. The US constitutional system makes it infuriatingly difficult to take prompt and decisive action. Its government of professional experts and bureaucrats is large and arguably has interests of its own. But between them, they tend to minimize the chances of truly egregious mistakes. In Turkey, strongman Recep Tayyip Erdogan can drive through an absurd attempt to reduce inflation by cutting interest rates. In the UK, Liz Truss, with a majority in the House of Commons behind her, could force through unfunded tax cuts just when interest rates were rising. In the US, separation of powers (and to a lesser extent the permanent government bureaucracy) can generally be trusted to ensure such errors don't happen in the first place. That strengthens the US role as the trusted keystone of global finance. The tariffs announced last week were a big and grievous mistake — at least as bad as those made by Truss and Erdogan. That is particularly the case if you share the tariffs' stated goal of peeling back globalization and allowing for the return of US manufacturing jobs; they're a terrible and wrongheaded way to achieve those goals. Investors are taking it as a given that they cannot possibly be imposed for any significant period. But this president has made it a lifelong principle never to apologize or admit error. How, then, can the administration correct its course?  Miran reaches for Churchill. Photographer: Stefani Reynolds/Bloomberg The way the administration has entrenched itself against the criticism makes it ever harder for them to step back. Donald Trump himself threatened Monday to add an extra 50 percentage points to tariffs on China if Beijing goes through with raising its own levies on the US. Stephen Miran, the chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors, who is seen as a principal architect of the policy, used Churchillian language in a speech defending the US approach: Americans have been paying for peace and prosperity not just for themselves, but for non-Americans too. President Trump has made it clear that he will no longer stand for other nations free-riding on our blood, sweat, and tears, whether in national security or trade.

Such words make it hard to admit defeat. A month ago, it was assumed that a run on the stock market or a collapse of consumer sentiment would ensure that tariffs were moderated. That was wrong. A serious pickup in inflation might have more of an impact, but we have to wait a while before that shows up in the figures.

So how is the course correction to happen? There are two broad options. The first is that Republicans in Congress decide to act. They hold majorities in both chambers, and there is a long tradition of the Senate being the arbiter of the crucial decisions on the US role in the world. A century ago, the US decided not to join the League of Nations, the creation of President Woodrow Wilson, because the Senate wouldn't accept it.  Ackman thinks things are moving too fast. Photographer: Jeenah Moon/Bloomberg In the last few months, senators have been cowed by threats that the president's backers will sponsor primary challenges against them. He is perceived to have a strong mandate. But there is movement. Rand Paul and Ted Cruz, both prominent senators on the right of the party, have spoken out against tariffs. A bipartisan bill that would curb presidential tariff power doesn't have the necessary support from the Republican Senate leader, but shows public flickers of intraparty opposition. Key presidential backer Elon Musk has been criticizing tariffs in an increasingly acrimonious spat with trade adviser Peter Navarro. Bill Ackman, the prominent hedge fund manager who publicly switched his support to Trump last year, has argued for a tariff delay. None of this on its own will move the White House, but does at least suggest that Congress could reassert its power. Rather than wait for Congressional Republicans, the key for a market recovery could be a move by a competitor that makes clear that tariffs are indeed negotiable, giving the administration a reason or pretext to back down — or at least delay. Jordan Rochester of Mizuho Securities puts it as follows: The true moment for risk to find a base will be when concessions are made by one or two countries to allow for Trump to announce a delay on reciprocal tariffs. It would be a sign that analysts' expectations of watered down tariffs could be proven true. But we need the first domino to fall, as simply delaying the broader reciprocal plan without it would be a serious challenge to Trump's credibility in negotiations.

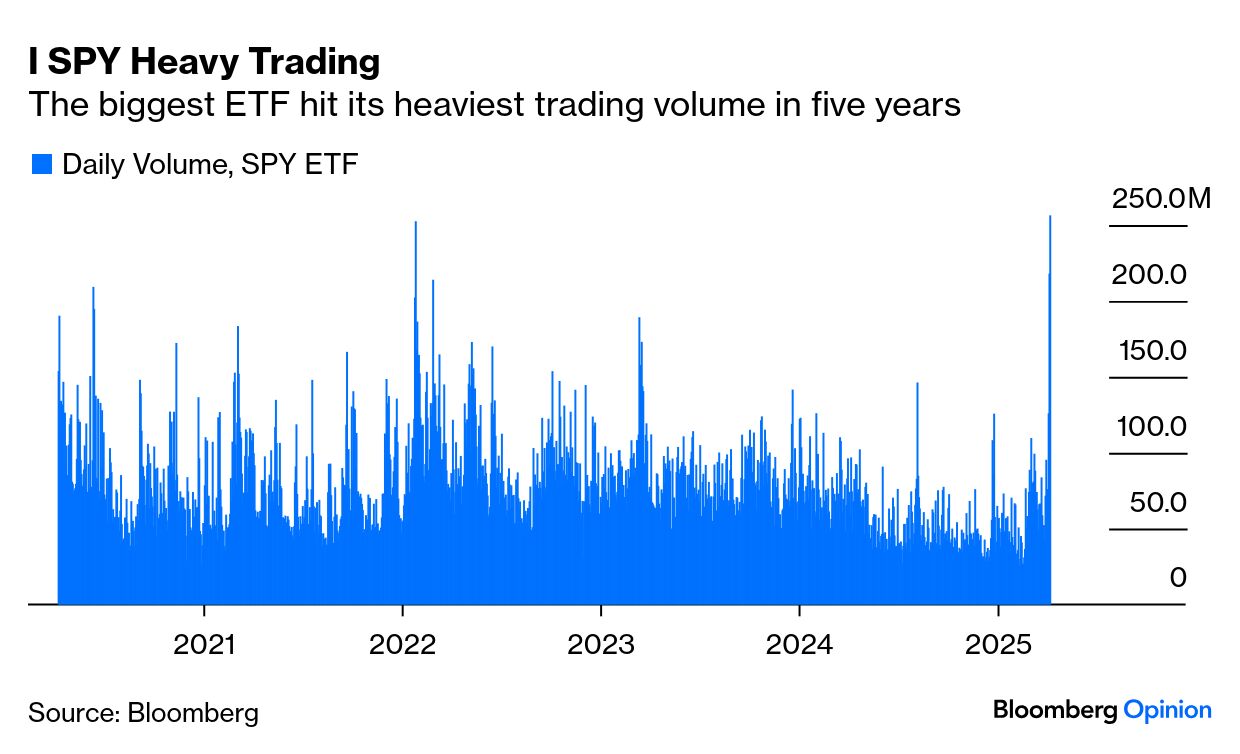

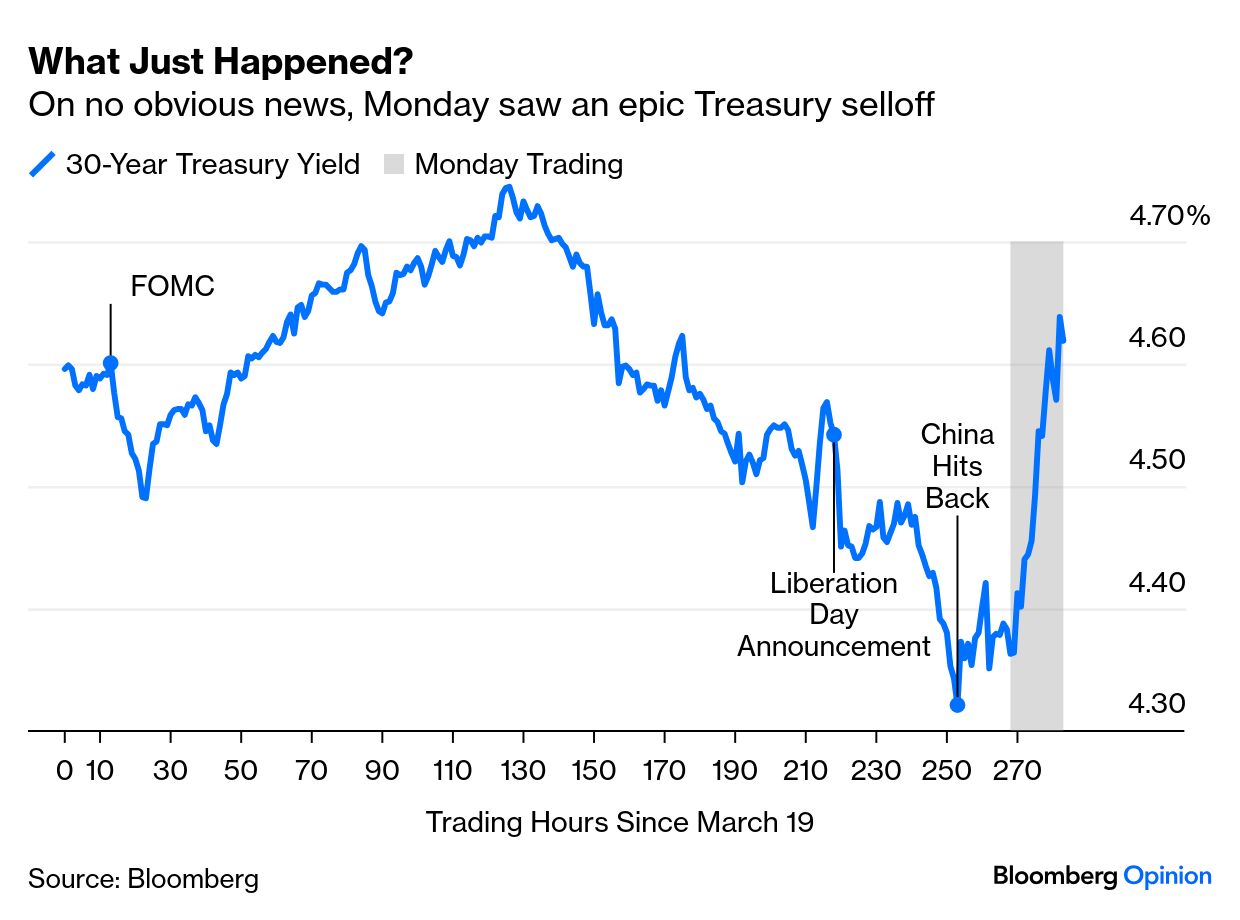

This selloff is driven almost exclusively by the policy change, and the implications the new tariffs have for company profits and economic growth. This means that only a change in the tariffs, though probably only a modest one, will move the market. Nicholas Colas of Datatrek Research says: Until there is an explicit catalyst to show markets the worst-case scenario (last Wednesday's announcement) is off the table, stocks will continue to be volatile (at best) or decline (at worst).  Xi Jinping takes the time to meet with global business leaders. Photographer: Philip Glamann/Bloomberg

Realistically, no big concessions are coming from China, which has allowed the yuan to weaken almost to its lowest point since 2007 in an unmistakable declaration of intent. The problem for other countries is that they don't have much to offer. Contrary to the rhetoric, the EU doesn't have big trade barriers against the US. Even Vietnam, which has a huge trade surplus, only levies tariffs of about 5% on American imports. Removing those barriers, as it's offered to do, will make minimal difference to US businesses, and Navarro has already said that it would not be enough. A further problem is that the ferocity of the US rhetoric makes it politically hard to concede. Voters don't like it when their leaders give in to a bully. But the administration is happily talking up approaches from other nations, and Trump himself says he is open to negotiation. He needs an excuse to step back — whether he admits it or not — and his friends in the business world have offered the possibility of a 90-day negotiating delay as an elegant way out. If someone gives the administration a needed excuse to step back, that could draw a line under the selloff. |

No comments:

Post a Comment