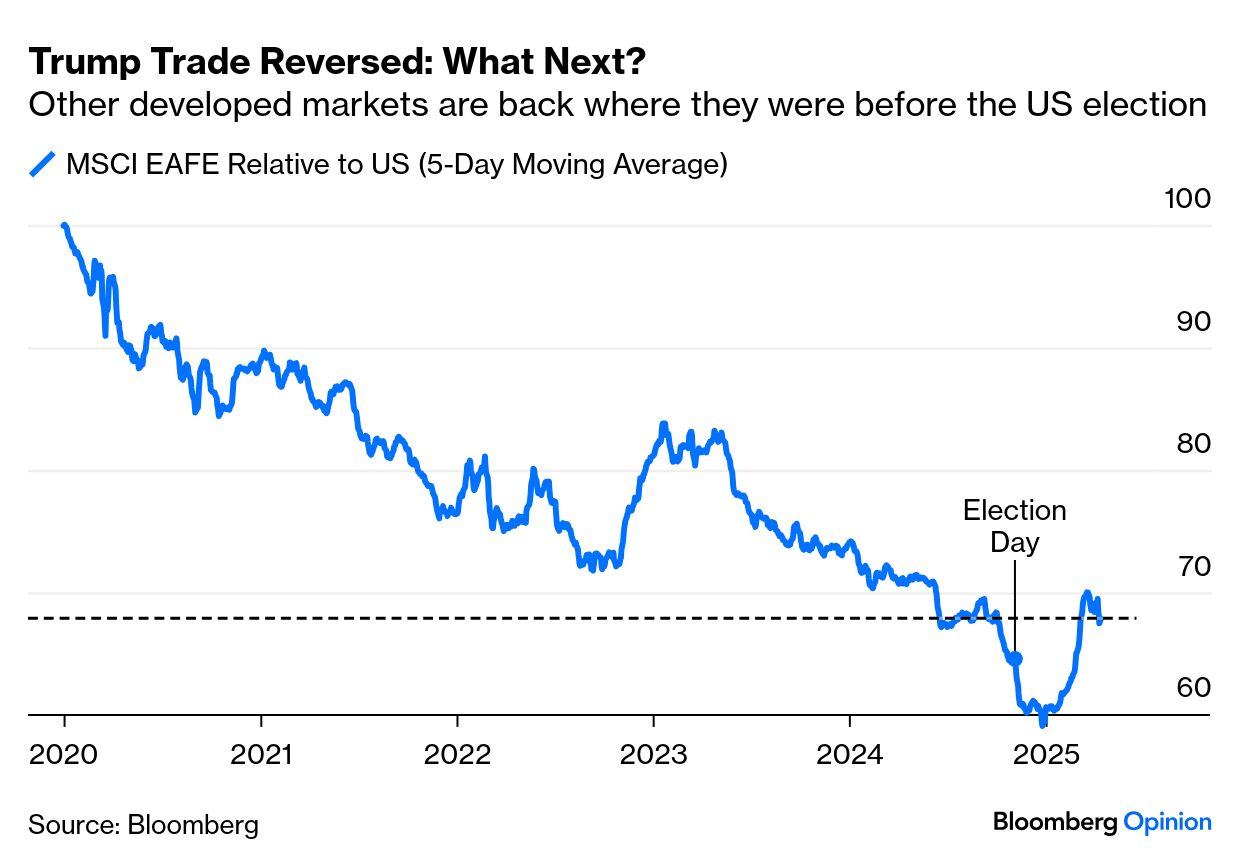

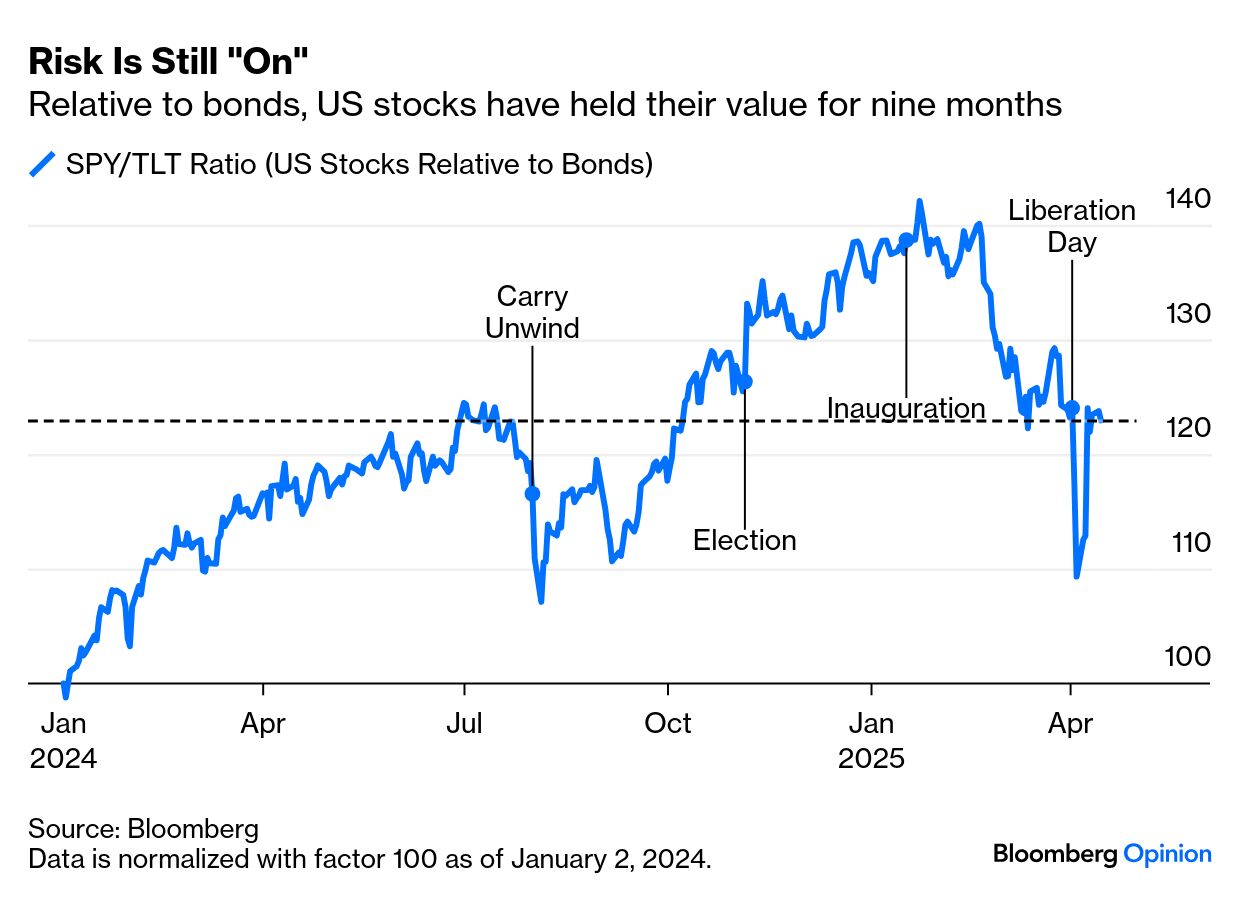

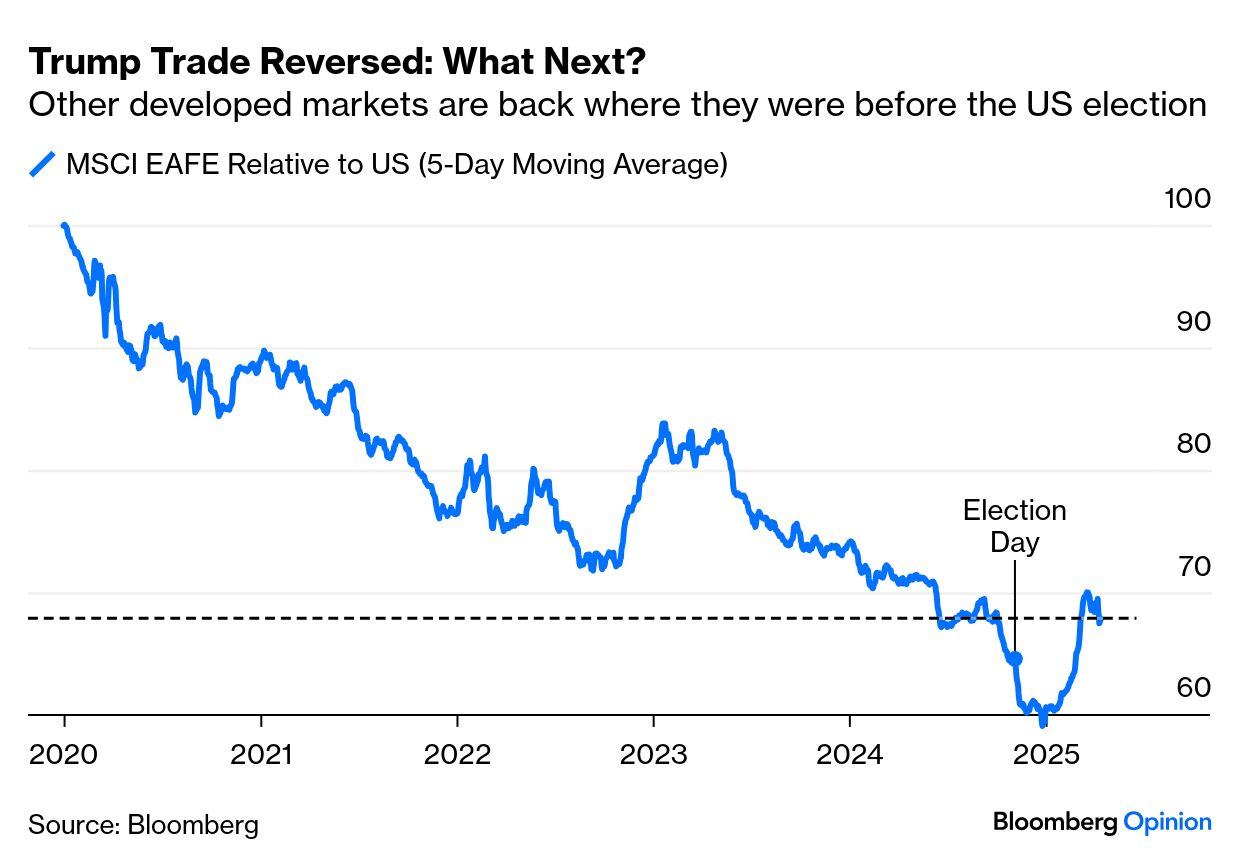

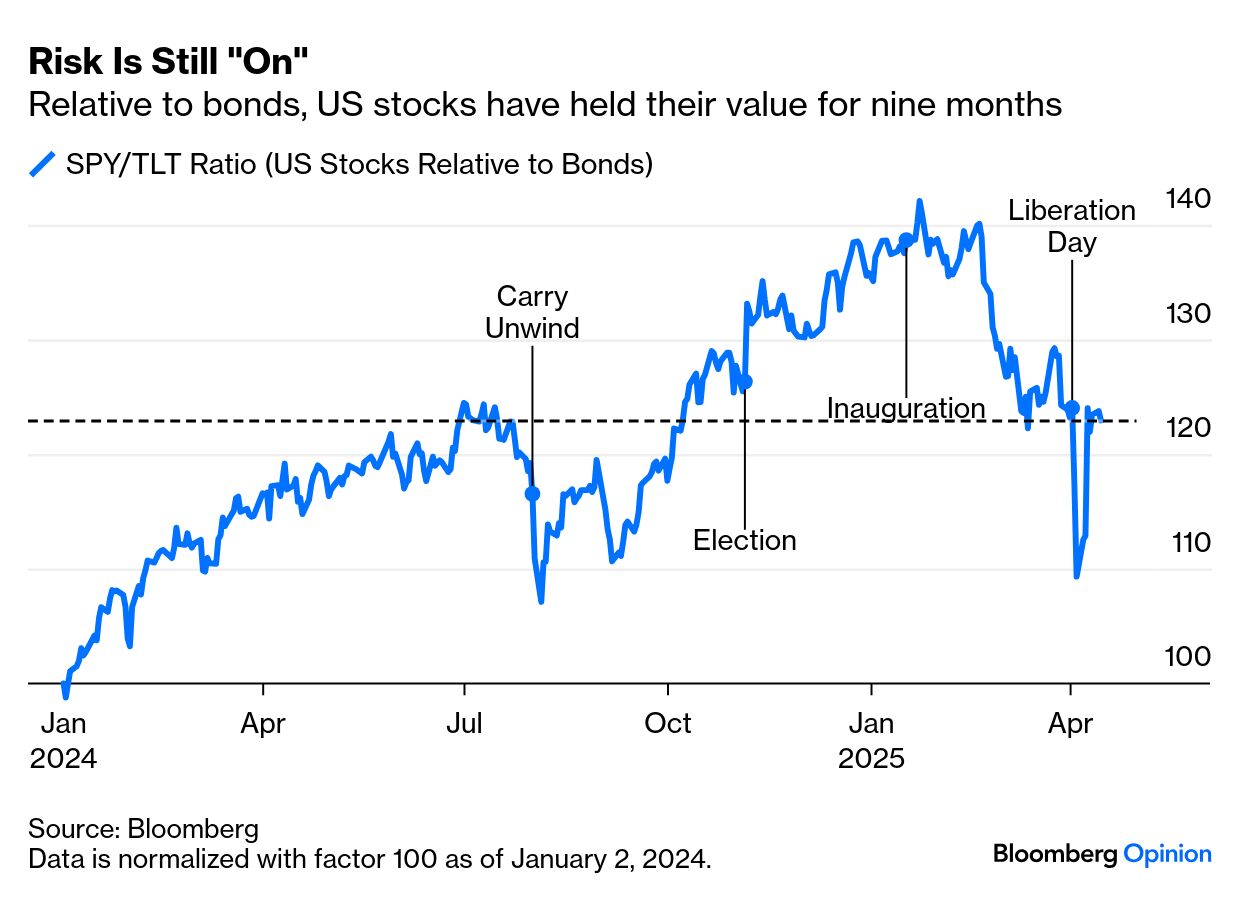

| Markets have settled into an eerie calm this Holy Week. But that doesn't mean that the pressing issues confronting investors have been resolved. Rather, trade uncertainty has been ratcheted up to a previously unimaginable level, and remains higher than it was before the April 2 "Liberation Day" tariffs. The old saying that markets hate nothing as much as uncertainty is irritating but true. And it remains extreme: Nothing has truly been resolved. Instead, it's better to say that the enthusiastic post-election "Trump Trade," which involved pouring into US assets over anywhere else, and favoring risk assets, has been reversed, with no clear new direction to replace it. That shows the relation of the MSCI EAFE index, covering developed markets outside the US, to the S&P 500. It has canceled out an extreme post-election dip, but hasn't seriously retraced the ground it had lost since the pandemic:  A similar pattern has emerged in the relationship between stocks and bonds, proxied by the SPY and TLT exchange-traded funds which follow the S&P 500 and 20-year Treasury bonds. Stocks boomed and then busted after the election, and then underwent a screeching fall after "Liberation Day," which has been reversed. As it stands, stocks have lost no ground to bonds in the last nine months — and the tariffs shock we have just experienced was little worse than the brief market seizure that followed the sudden strengthening of the Japanese yen last summer:  Markets are maintaining a nervous calm in part because it's a holiday week, but primarily because two key questions must be answered before they can set a clear new direction. Neither can be resolved quickly. The first is what kind of tariff regime will finally result, as this will largely determine a new global trading system. That system has already changed greatly since the Trump 1.0 trade conflict, as China has attempted to diversify away from the US, but the extent of enduring new barriers to trade is still unknown. The second concerns the risk that trust has been so damaged that foreign capital will stage a disorderly exit from the US. Trading in the last six months has been a series of switches between two narratives: - The Mar-a-Lago Accord idea that the US can pull together a grand deal in which everyone pays them some money and agrees to weaken the dollar in return for no tariffs (and a security blanket). Many minor elements of such an accord might still be reachable with individual countries. The message from US behavior of the last few weeks is that a true accord to match the Plaza Accord of 1985 is out of the question. Nobody will trust the US enough to do a deal. That leads to the other narrative:

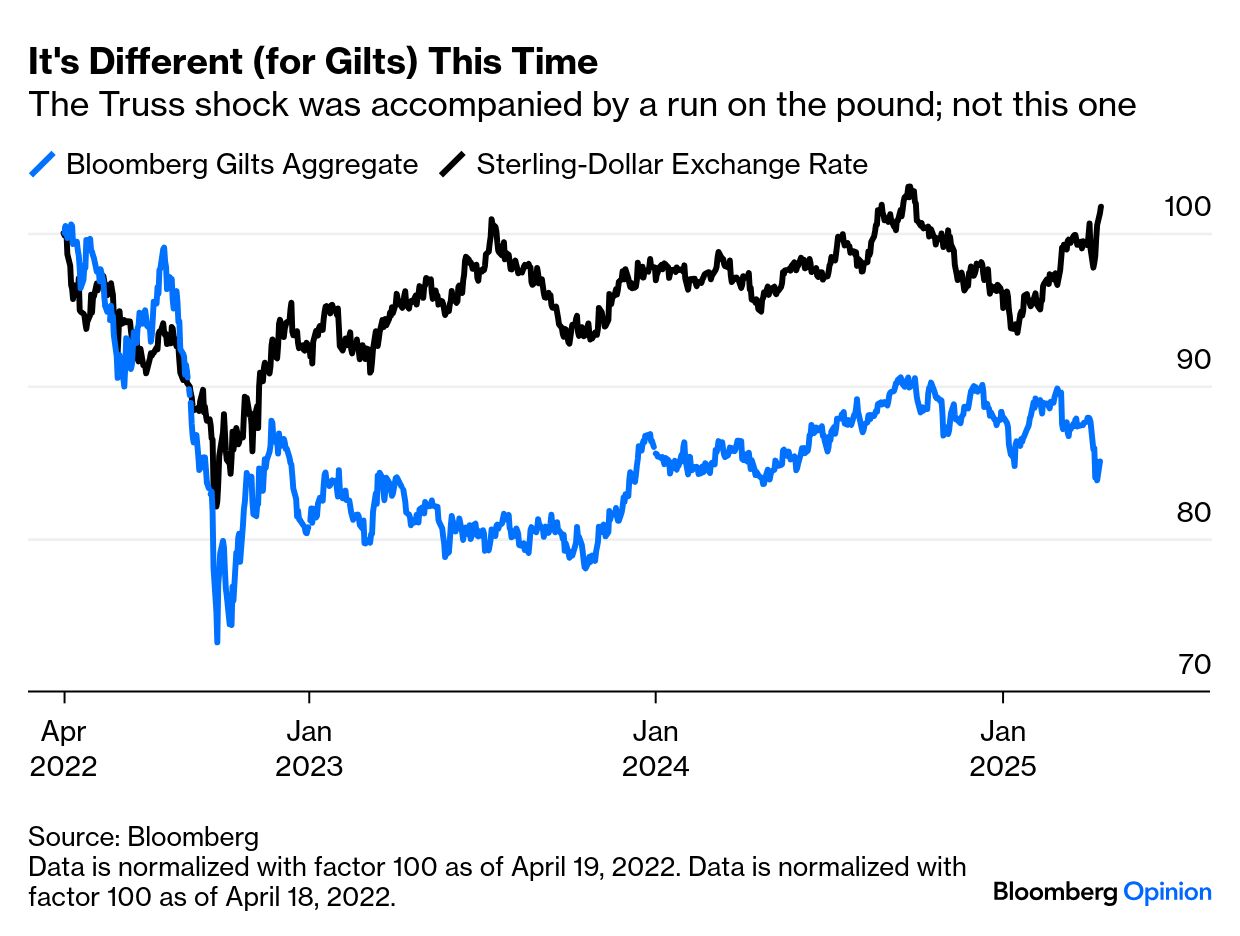

- Exodus From the Dollar. On this theory, the US overplays its hand, in both defense and foreign policy, the rest of the world decides it is no longer to be trusted, and the huge sums of foreign capital in the US go home in a rush, prompting a vicious circle. The US stock market crashes and Treasury yields surge as the Trump administration belatedly realizes that it had been getting quite a good deal out of being nice to their its allies.

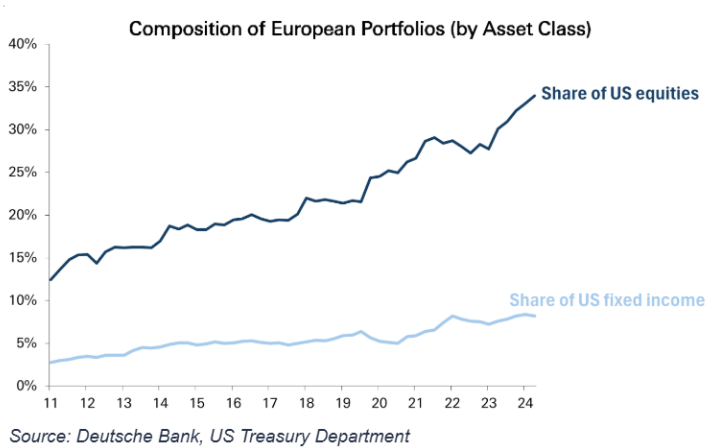

Both scenarios end with a weaker dollar, but the second has received more attention of late as Treasury yields climbed while the dollar fell. The rise in US asset valuations has left other countries — not just China — with massive holdings that they might want to repatriate. George Saravelos, head of FX research at Deutsche Bank AG, shows that since 2010, foreign ownership has risen by $3 trillion in bonds (almost doubling) and by $15 trillion (a sixfold increase) in equities. Some 90% of this was driven by rising market prices rather than new flows, but it means Europe is far more exposed to the dollar than it used to be: Saravelos said: The more benign interpretation of our analysis is that foreigners have merely passively tracked rising aggregate valuations of US equities and issuance of US bonds. The more worrying interpretation is that this has left foreigners - especially Europeans - with a huge overweight in their portfolios relative to history, especially in US equity markets which tend to be currency unhedged.

This latter option is much more alarming if the trust the US has accumulated over the last 75 years has been lost. Trust is like a 1.000 average in baseball — once lost, impossible to get back. If that's the case, foreign investors will feel obliged to pull out, which could then starve the US of capital. Steven Englander of Standard Chartered PLC puts it as follows: Public and private investors may see the announced tariffs as reversible, but not the confidence loss from one-sided policy announcements that have overthrown decades of precedent on trade relationships and the conduct of negotiations… If tariff policy can be dictated by one side and enforced by economic threats, what is to stop analogous policy decisions on bonds and other US assets held by non-US residents?

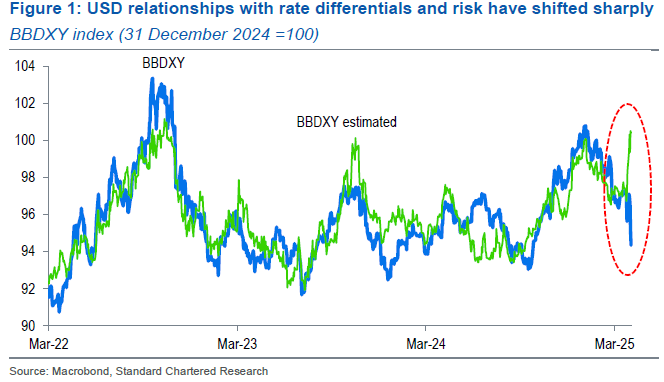

If there's evidence of a loss of trust, it comes from the interaction of the dollar with bond yields. Usually, exchange rates are driven in large part by interest rate differentials — money flows to places where it will be paid higher rates. The following chart shows the actual performance of the broad Bloomberg dollar index (in blue) with the performance that could be predicted by rates. The sudden divergence in recent weeks suggests a sudden shock to trust: |

No comments:

Post a Comment