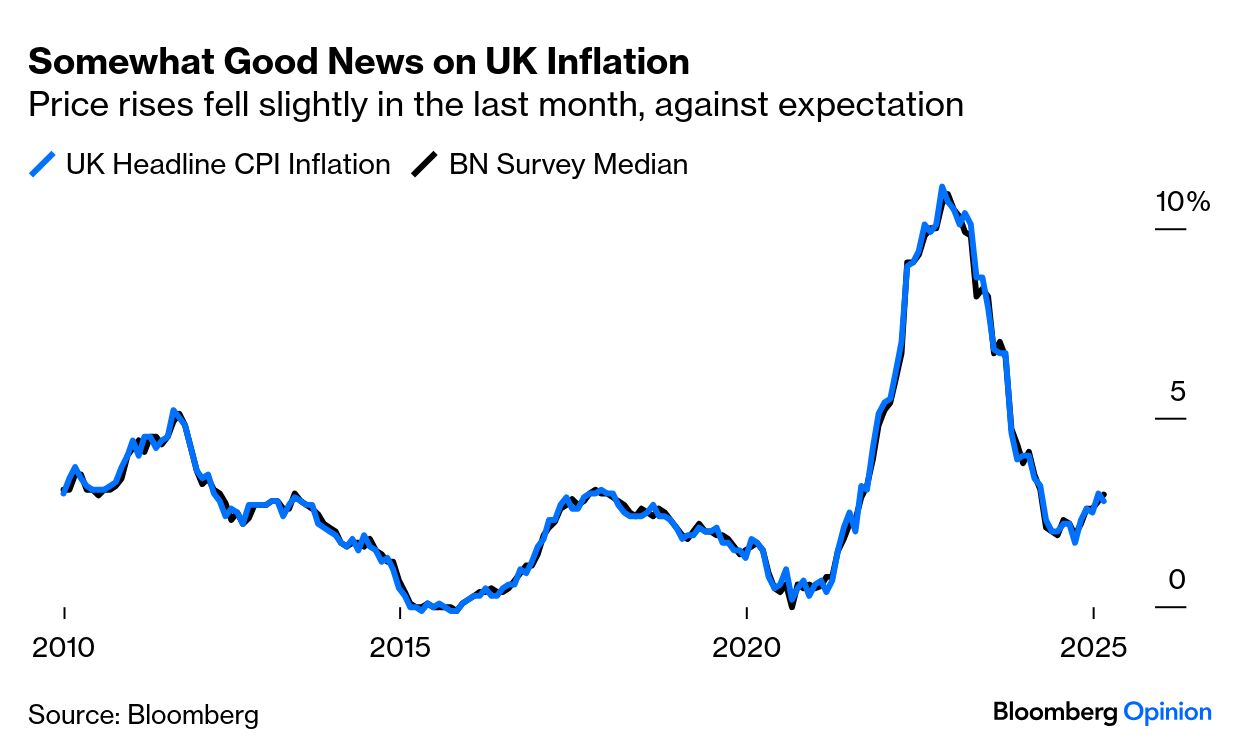

| Rachel Agonistes was painful to watch. Rachel Reeves, installed last year as Britain's chancellor of the exchequer, has done what politicians of the left least want to do, and reduced welfare benefits for the poor. Cuts of £4.8 billion ($6.2 billion) understandably dominated coverage. They will be concentrated on 800,000 people with long-term physical or mental health conditions who have difficulty doing certain everyday tasks and receive personal independence payments (PIPs). The optics for a Labour administration could scarcely be worse. That said, Reeves passed muster with the markets. She had gone on a media tour to break the bad tidings in advance, so they didn't come as a surprise. She was also helped by a pleasant surprise on UK inflation, which has turned back down slightly: Gilt yields dropped and the FTSE-100, alone among major European indexes, gained for the day, while a bad outing for sterling still left it almost exactly at $1.29, the level at which it has been trading most of this month. Reeves survives. But there are problems ahead, with another fiscal statement due in the fall. Sam Cartwright of Societe Generale SA complained that the government was left "exposed to unfavourable movements in the forecast yet again." He said that a fall in productivity in the Autumn Budget or proof that spending plans couldn't be delivered "could force the Chancellor into raising taxes." That is a problem because Labour made a necessary election promise not to raise taxes on the working class. It's also trying to keep within two fixed and self-imposed fiscal bounds: That the budget should be stable, so day-to-day spending is met by revenues, and that public sector net liabilities should be reduced as a share of gross domestic product by the end of the parliament. These rules were a needed inoculation after the bond market's revolt at former Prime Minister Liz Truss' unfunded tax cuts in 2022 — but led to extremely uncomfortable welfare cuts.  Still squeezed. Source: UK Parliament The UK's non-partisan National Institute for Economic and Social Research argued in its response: This exercise in fiscal tinkering, which will have a material impact on some of the economy's most vulnerable, was done in the service of self-imposed fiscal rules. While these rules are supposed to ensure the sustainability of public finances, the focus has shifted to a point where meeting them has been prioritised over fostering a long-term fiscal strategy conducive to growth.

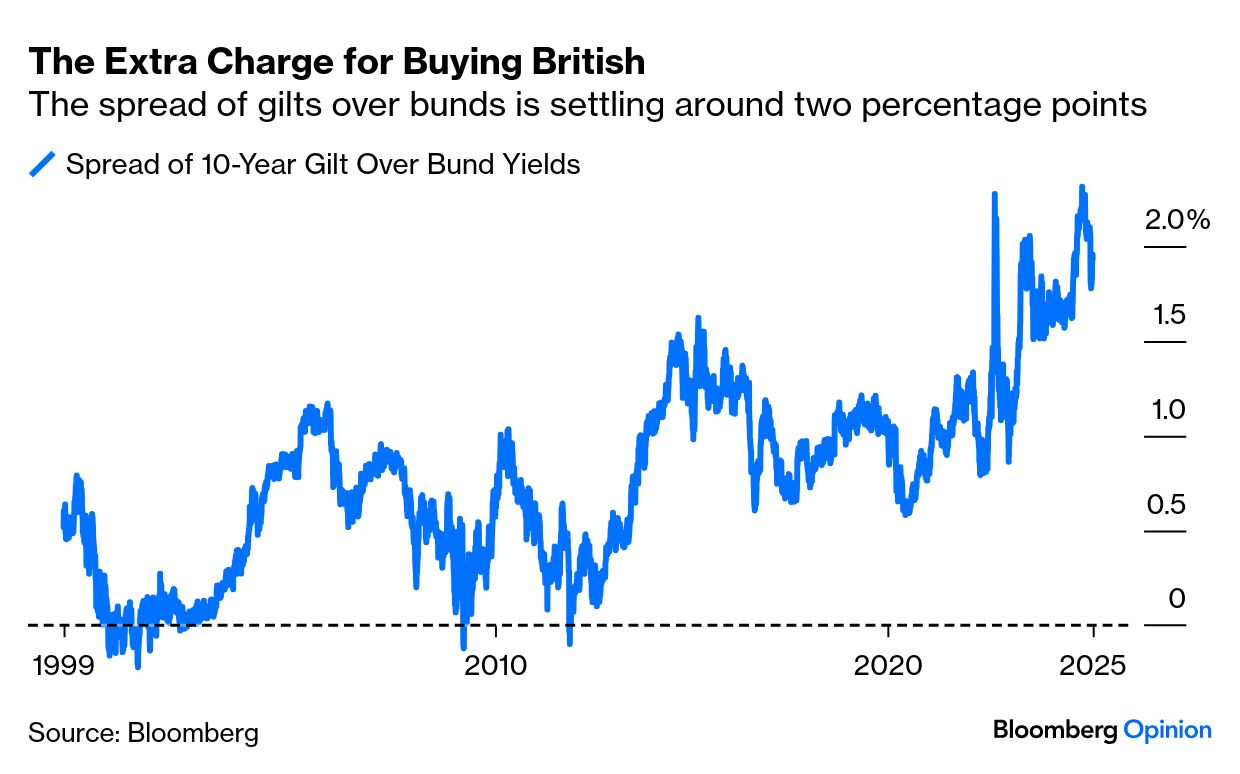

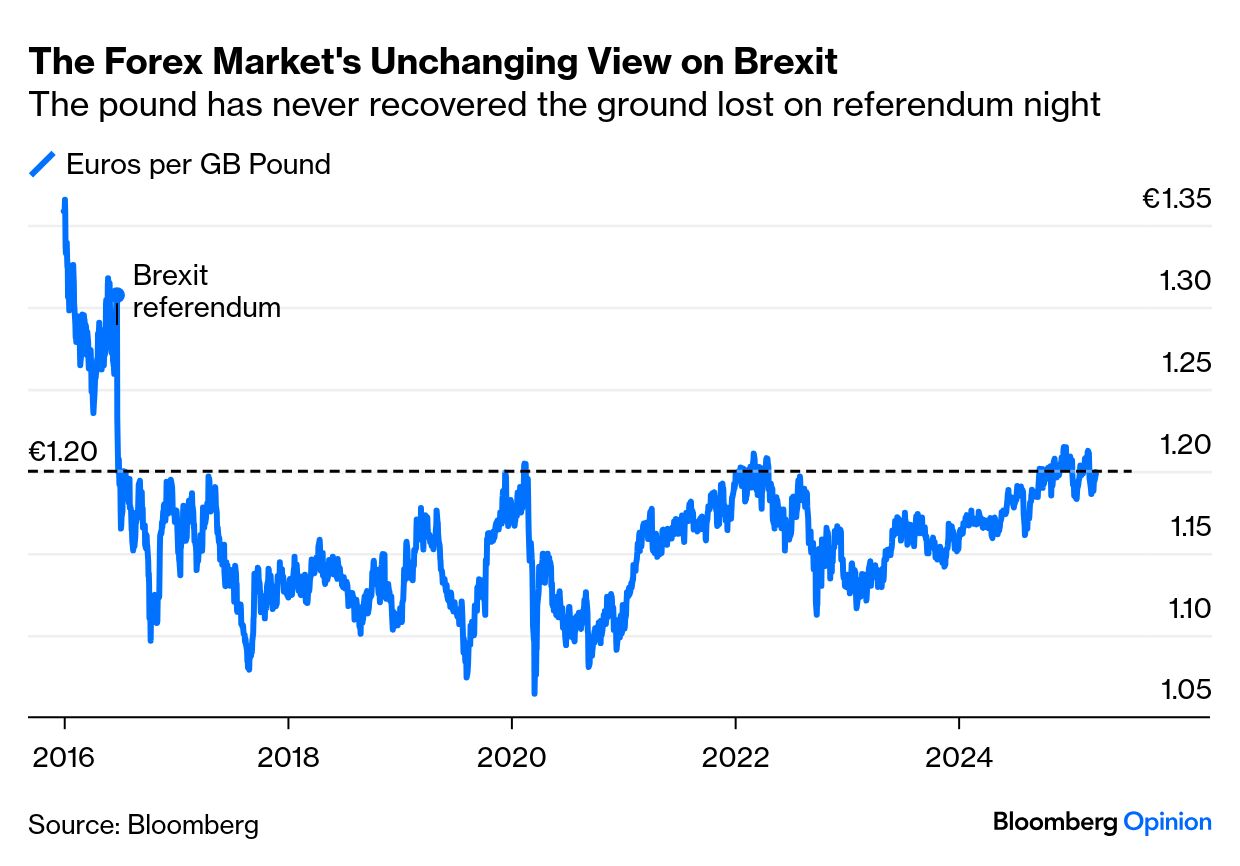

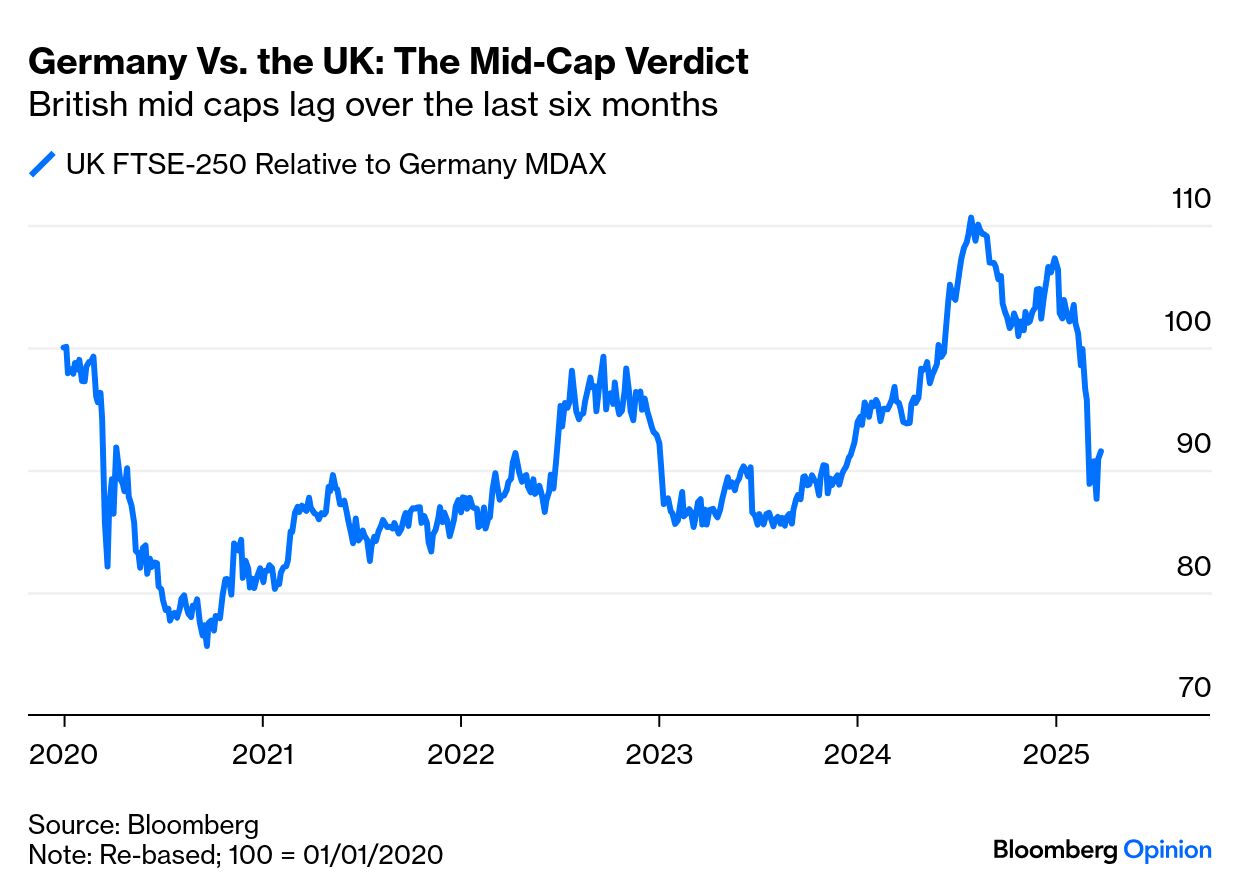

Operating with very little headroom, Reeves is vulnerable to further changes in the economic outlook. The Office for Budget Responsibility avers that 20% tariffs from the US would be enough to wipe out all the savings she has just made. The contrast with Germany is stark. The UK elected a Labour government which is presiding over sharply tighter fiscal policy, while Germany just elected fiscal conservatives who are now overseeing a massive fiscal splurge. That's not what the voters or even the politicians themselves had in mind. But it's critical to note that Reeves isn't subject only to her own rules. Markets are also setting guidelines. Despite the huge change in the borrowing intentions of the two countries this month, the bond market still sees German debt as much, much safer. The extra yield required of the British has risen steadily, and is now about two percentage points; a big obstacle to borrowing that Reeves did not impose on herself: Some of this is the continuing negative verdict on Brexit. As far as financial markets are concerned, Britain would have been a safer bet if it had stayed in the European Union. The consistency of this judgment is impressive. It's now almost nine years since the UK voted to leave, sparking an unprecedented overnight nosedive for sterling. That's held up, with the pound at a permanently lower level against the euro, and unable to get back above its level after the hectic referendum night: Stock investors seem sure that German prospects have improved dramatically. Comparing British and German mid caps — most directly exposed to their domestic economy, as their ranks include few multinationals — is startling. Amid previous negativity around Germany, the FTSE 250 put in a period of outperformance. It's given that all up, and then some, as the new German policy has taken shape: Germany faces its own challenge, to spend these huge sums well. We have the first round of sentiment surveys since the wave of fiscal announcements. They suggest that business sentiment has improved, but perhaps not as much as might have been expected. The ZEW survey showed expectations at the highest level since the invasion of Ukraine, but the rival IFO survey was more constrained. Investors have plainly perked up a lot; the manufacturing PMI index remains at a level that normally means contraction: For now, the market is still giving Germany rather more than the benefit of the doubt over a massive policy shift that could easily go wrong. The country is using that flexibility, which has been earned with a generation of arguably excessive austerity. Britain's different policies have left Reeves without room to expand. She doesn't get the benefit of any doubt, and she's playing the miserable cards she's been dealt about as well as anyone could hope. |

No comments:

Post a Comment