| The idea that the US is entering a new golden age has been a theme of President Donald Trump's second term so far, reiterated in his address to Congress this week. Max Abelson talks today with a historian who sees echoes of the Gilded Age in our current times. Plus: An all-American ETF empire draws scrutiny, and car dealers confront more direct-to-consumer sales. If this email was forwarded to you, click here to sign up. "The golden age of America begins right now," President Donald Trump said in January's inaugural address. The next morning, Yale University historian Beverly Gage told her students that she couldn't stop thinking about the Gilded Age, a chapter beginning in the late 19th century marked by rapid technological change as well as stark inequality, corporate graft and violent clashes between workers and bosses. As it happens, the Mark Twain book that gave the Gilded Age its name was also a source for the saying that history doesn't repeat, though it rhymes. For Gage, the author of a Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of J. Edgar Hoover, there are several themes that tie our current era to one more than a century ago: the veneration and empowerment of business tycoons and also deep anxieties about immigration, empire and manliness. (This interview was edited for length and clarity.) What does the Gilded Age mean to you?

This is a period in the late 19th century, and some would say stretching all the way into the 1920s, in which capitalism fundamentally changes. You get the rise of large corporations, you get the rise of large corporate fortunes, you get the rise of large banks. That sets off a whole set of controversies and debates and instabilities in American political life. What would it mean for a Gilded Age to return?

We certainly have this valorization of the businessman in power—that's part of who Trump is. And also a kind of shameless grabbing of the public purse: the idea that all of this money that's in government (and there's a lot more of it now than there was) is there to be taken and pillaged and manipulated and used to create bigger and better fortunes for the fortunate few. We are in an age of inequality that looks an awful lot like what we saw in the late 19th century. What anxieties of the Gilded Age are still with us?

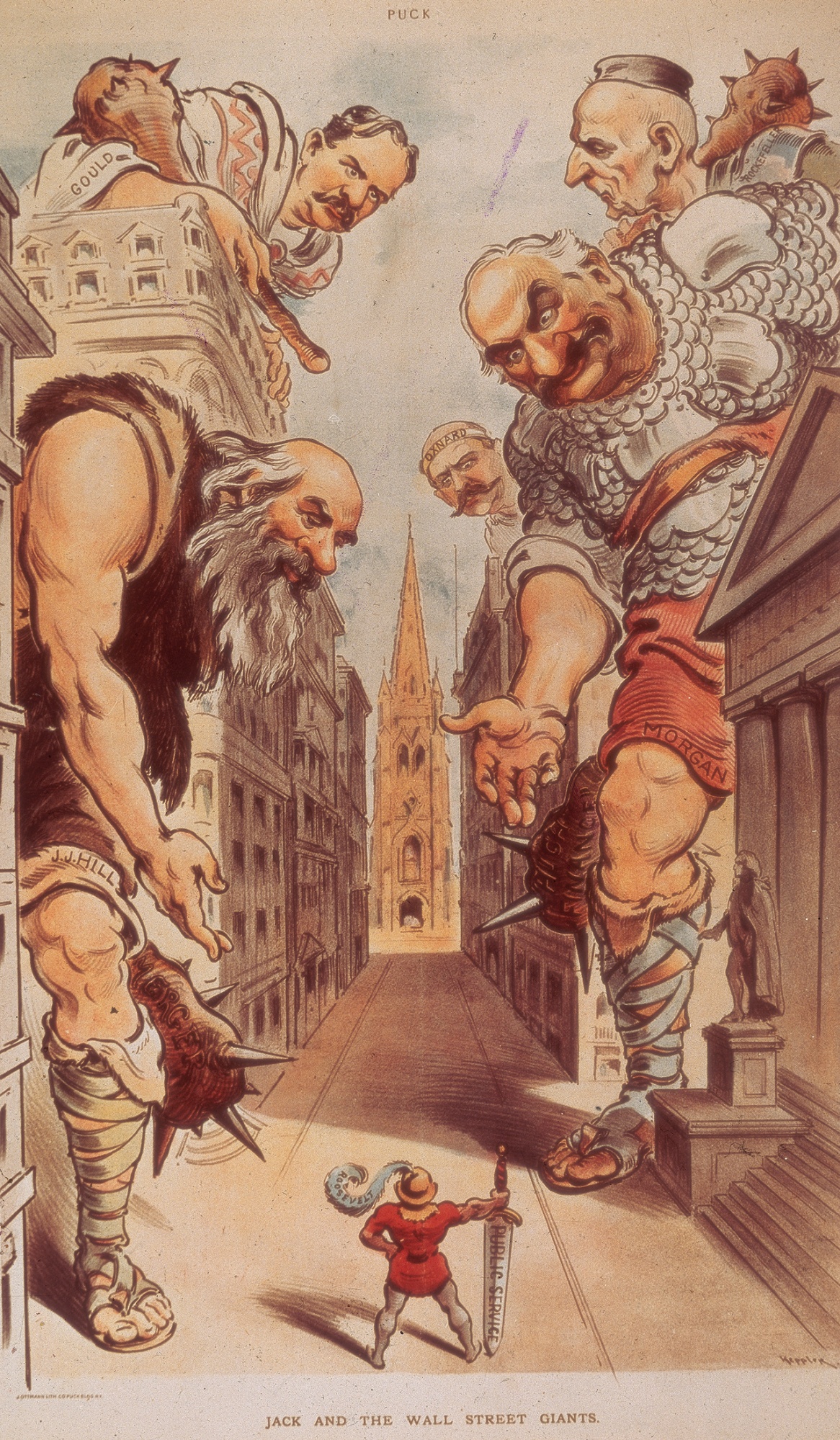

One is simply this anxiety that men aren't able to be men and that there's a crisis for boys. As the world of white-collar and corporate work came into being during those years, there was this anxiety that men who had been doing all this hard physical work, who had been entrepreneurs and all of these things, that they were going to become weak. Theodore Roosevelt is the great avatar of this strenuous masculinity: Get out of the cities, into the American West, remake things and be a strong man. And it goes along with two other things that we see in our moment. One is a kind of deep concern about racial hierarchy—what a lot of people would today describe as replacement theory stuff. That was very mainstream politics in the early 20th century, the concern that families are getting smaller, that White people aren't having enough babies and all these immigrants are coming in. People from all walks of life were actively articulating the idea that they thought that American democracy was about to collapse.  A diminutive President Theodore Roosevelt confronts Wall Street giants in a 1904 cartoon. Source: Getty Images What do you see when you look at the richest man alive today?

A lot of the anxieties about Elon Musk existed around figures like John D. Rockefeller, to some degree Andrew Carnegie, J.P. Morgan—the robber barons, which is a name that came out of that moment. Some of that is very familiar: anxieties about the ability of people with these giant fortunes to control the press, to control public opinion, to have outsize influences on government, on campaign finance, to basically pick the president. All of these were anxieties of the Gilded Age. I think Musk, in many ways, is a more extreme figure in his politics. Henry Ford is probably the best analogue: someone with a kind of wild array of strange political ideas. Is Trump's motto, "Make America Great Again," referring to the Gilded Age?

It means that there was some moment in the past when America was better: We've gone into decline, but we can restore the imagined greatness of the past. And one of the things that works about it is different people have different imaginings of when America was great. But his inaugural and what we're seeing now suggests that his vision of when America was great was before the progressive state had come into being, before there were income taxes and large government institutions and when the frontier was open. What have you learned about old eras of American politics that might be helpful to us now?

Americans tend to forget their history. This is maybe even more true, somewhat paradoxically, of liberals and leftists who tend to think that once a victory is won—civil rights, same-sex marriage—that it's permanent, and that all the old ideas have gone away and the new order has come into being. There's something of a cycle of people being surprised every 10 or 15 years or so to discover that, in fact, is not the case. There are all these points of continuity that are worth paying attention to—political styles, ways of being—that come back and are sometimes never vanquished. |

No comments:

Post a Comment