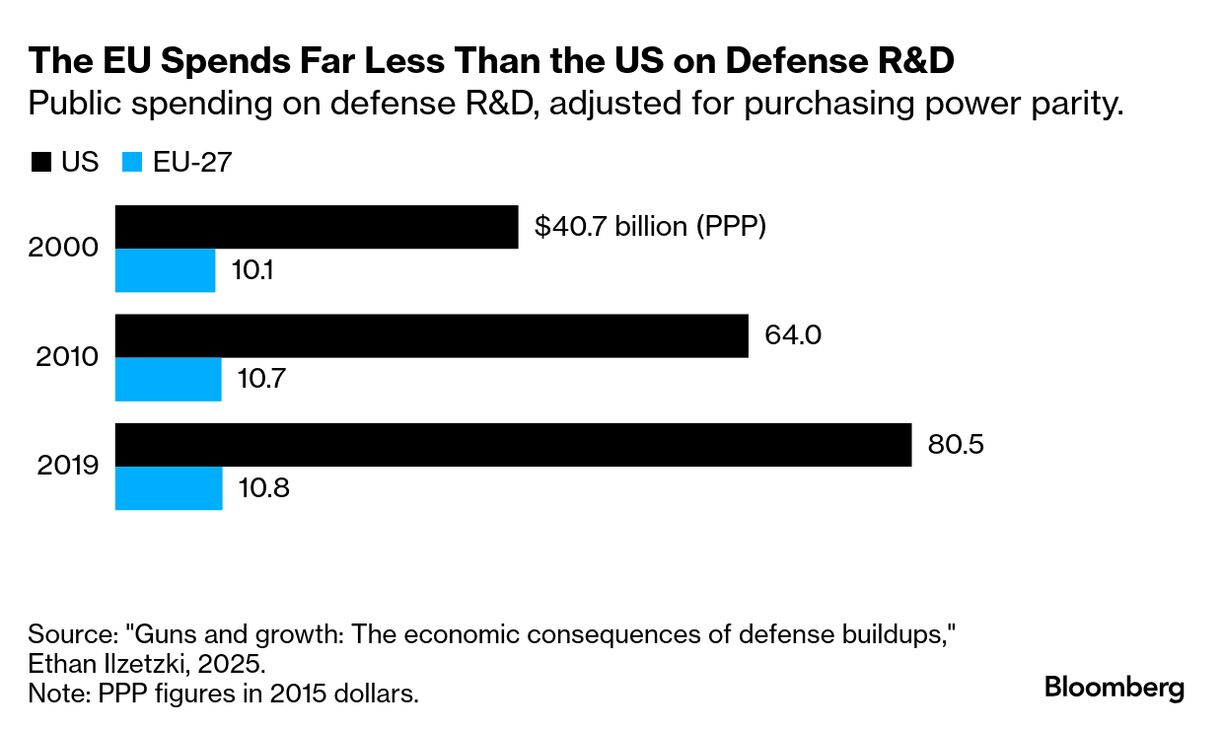

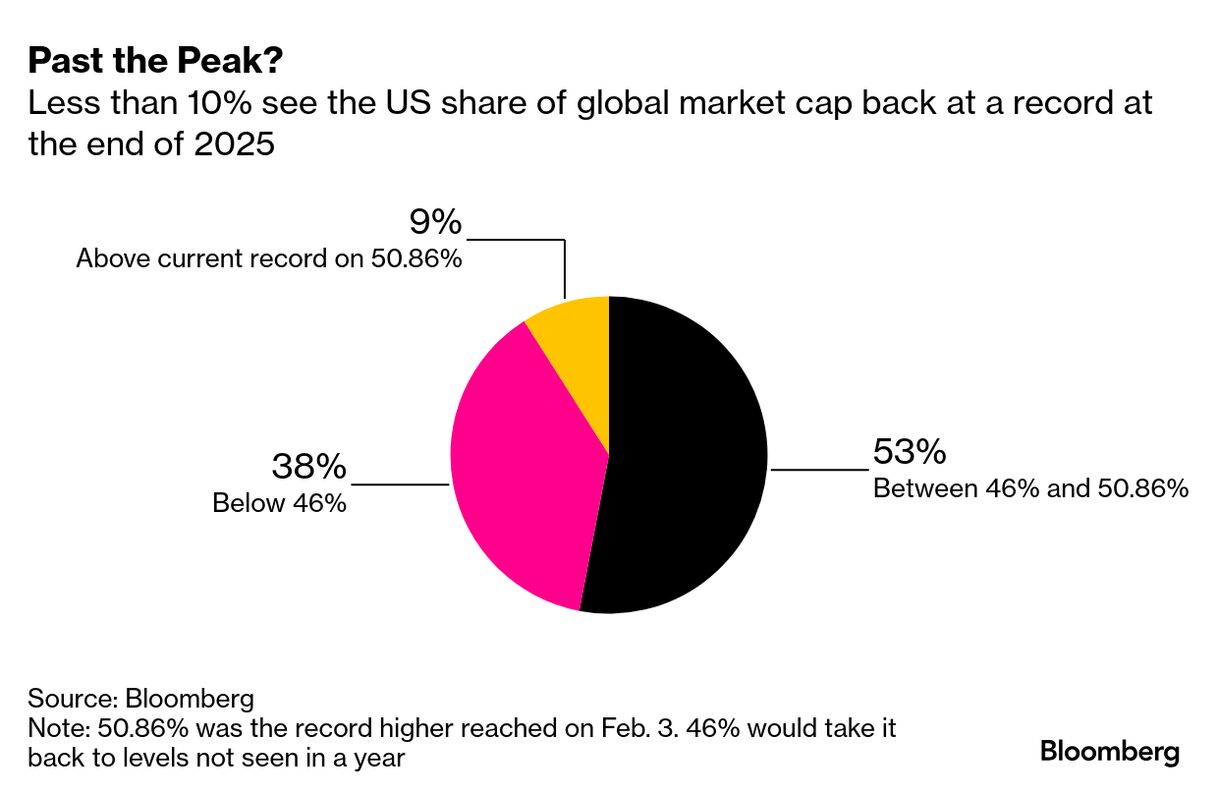

| In 1937, the US produced just 3,100 airplanes, mostly for private use. Over the course of World War II, it would be forced to produce 325,000, with a peak of 96,000 made in 1944 alone. In the face of unprecedented demand, sharp resource constraints and the urgency of war, US aircraft manufacturers had to invent and adopt new processes and become much more productive. Ethan Ilzetski, an economist at the London School of Economics, called it "learning by necessity." As Europe commits to spend more on defense, Ilzetski thinks the same dynamic could be in play, albeit at a much smaller scale. And he thinks the productivity gains from defense spending could translate into higher European productivity overall. "A transient 1% of GDP increase in military spending could increase long-run productivity by a quarter of [a] percent," he writes in a recent literature review titled "Guns and Growth." His logic is two-fold: Defense research can spark technological progress with civilian applications. And increasing the scale of defense spending means more "learning by doing" — like with US aircraft — which will improve production methods, again with spillovers to the rest of the economy. That's good news for Europe, which has pledged hundreds of billions of euros in new defense spending over the several years. But several facets of Europe's defense procurement would have to change to secure these productivity benefits, starting with buying less from the US. "Right now, the main impediment to defense spending buoying the economy is the fact that about 80% of military hardware comes from outside the EU, and much of that from the US," write Martin Ademmer, Jamie Rush and Antonio Barroso of Bloomberg Economics (Terminal subscribers only). European defense stocks have surged in recent weeks, suggesting markets think Europe will increase its domestic procurement — though it may take a while. Europe also needs to direct more procurement towards smaller companies, says Ilzetski. And it needs to find a way to centralize its efforts; it makes no sense for every EU country to have its own domestic procurement strategy, he says. Ilzetski suggests the EU could strike a balance between centralized, efficient procurement and spreading the benefits of spending around member countries. The US employs "dual sourcing," a policy of buying the same product from two separate companies. He suggests the EU employ a version of this, procuring products from at least two of its member countries. Ilzetski also thinks Germany needs to rethink its restrictions on universities' participation in military research. The benefits of defense spending also depend on what it replaces. Some climate advocates worry Europe's defense buildup will come at the expense of investment in clean energy. And there is some research suggesting that World War II ultimately hurt US productivity — because the military buildup meant fewer resources spent on roads, bridges and other domestic infrastructure. The EU has indicated awareness of these dynamics: A 2024 white paper highlighted the benefits of R&D that has both military and civilian applications. But while defense spending could boost European productivity, the dynamic works in reverse, too. A long line of research finds that wars are usually won by the country with deeper pockets. One way or another, Europe's security will depend on its competitiveness. — Walter Frick, Bloomberg Weekend Edition |

No comments:

Post a Comment