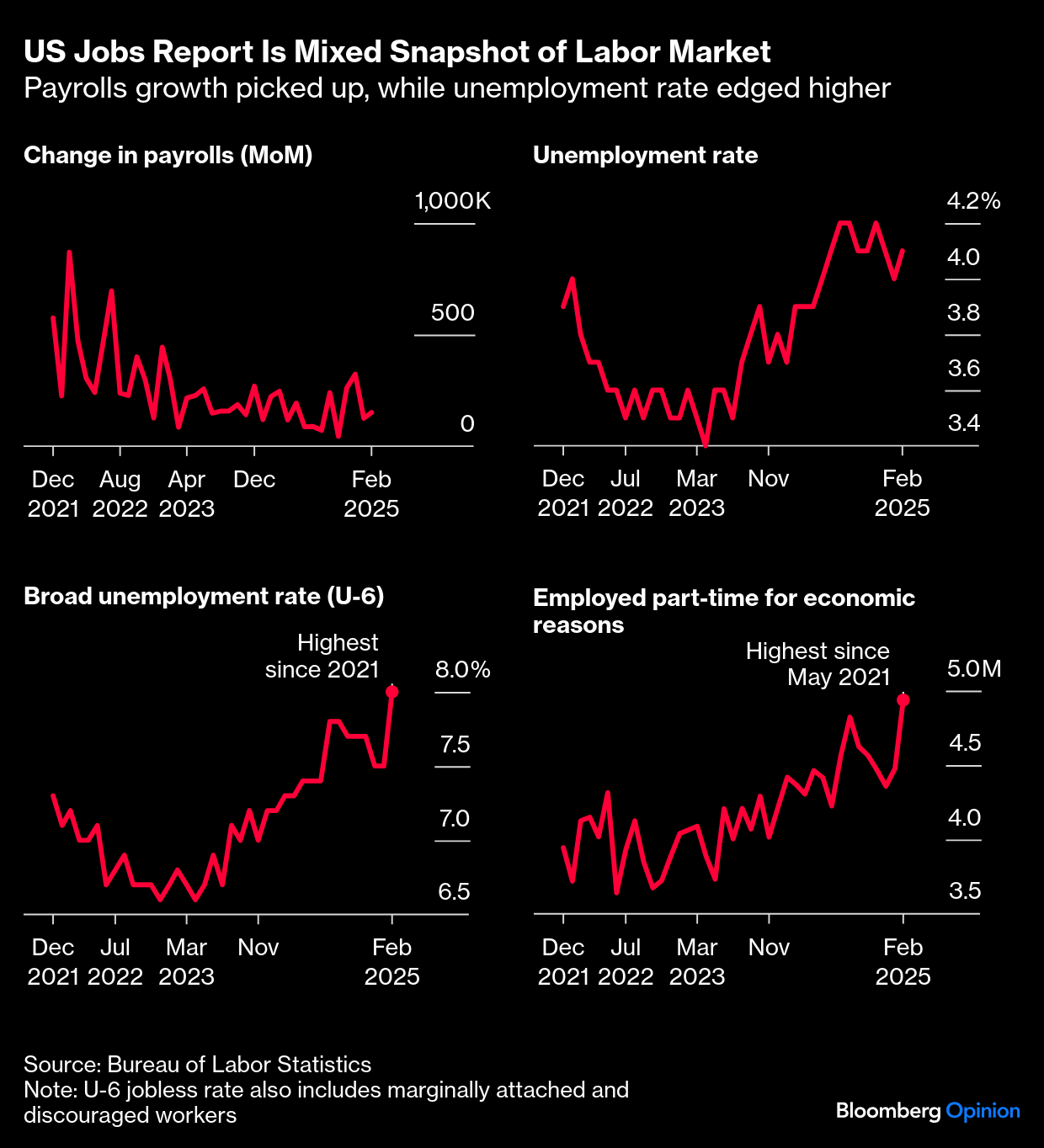

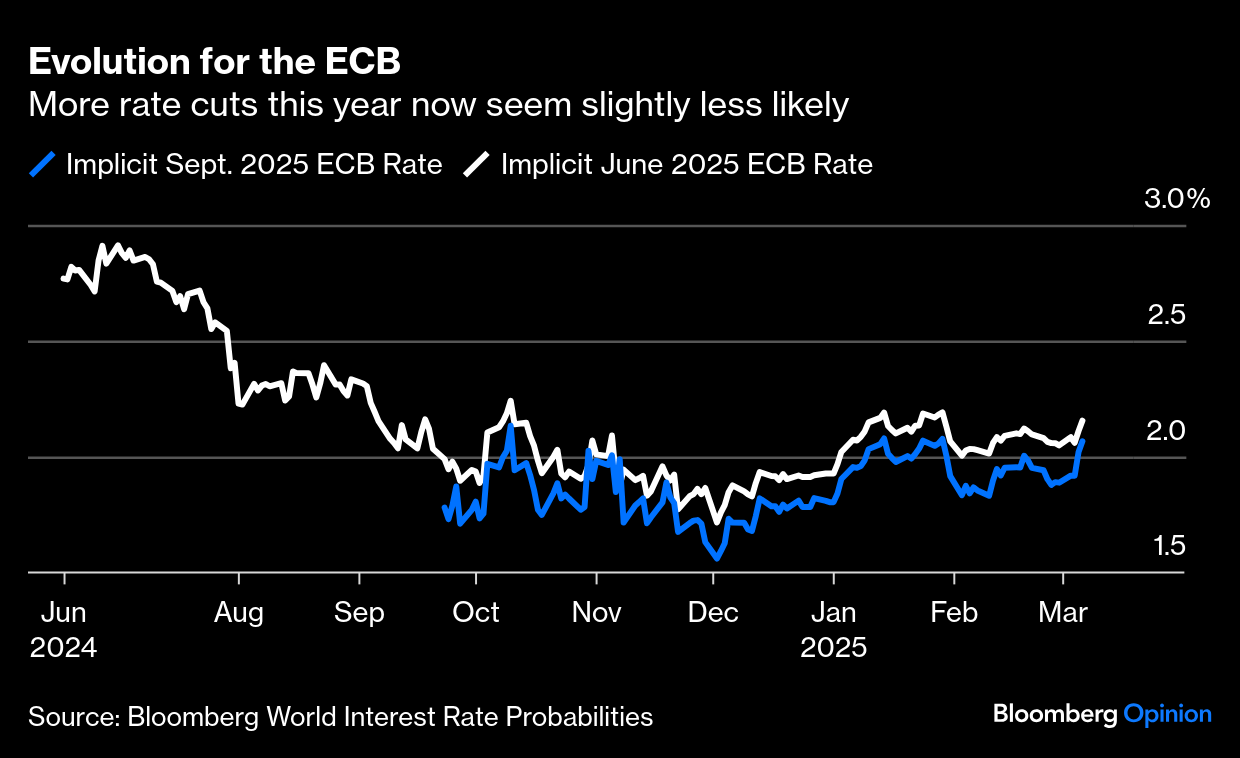

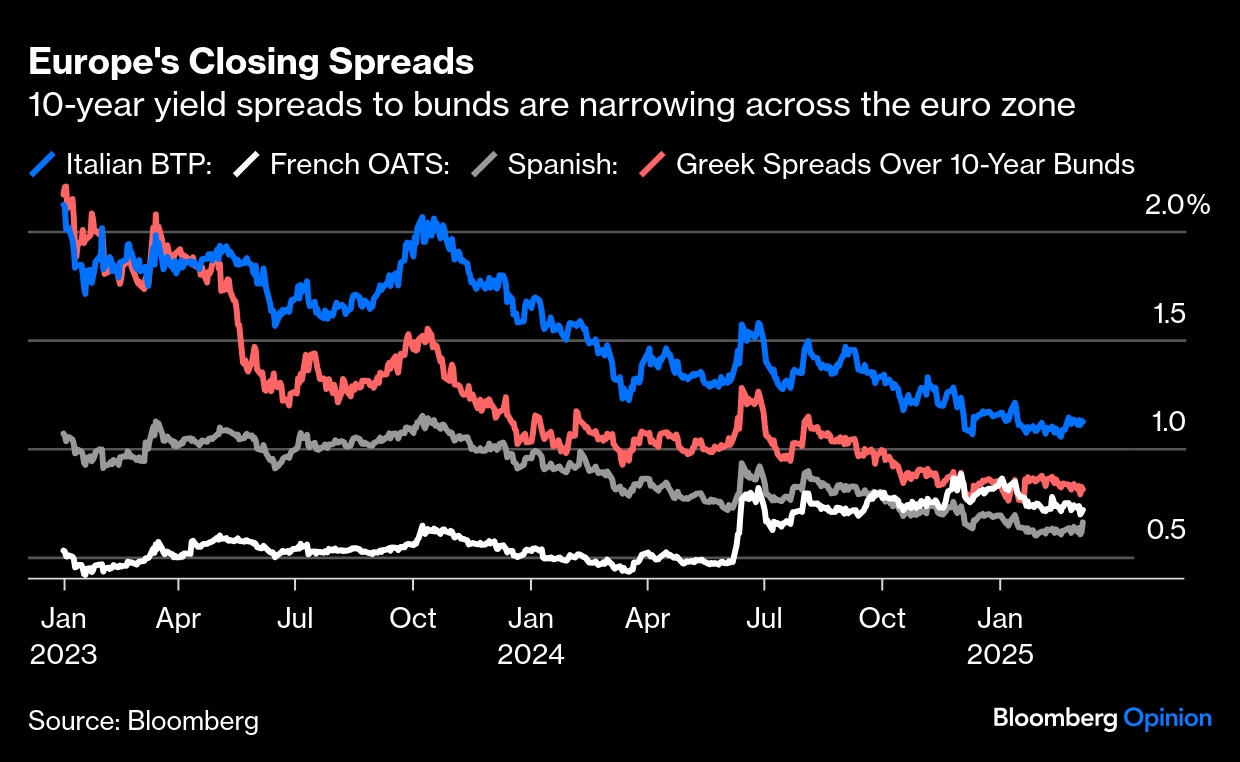

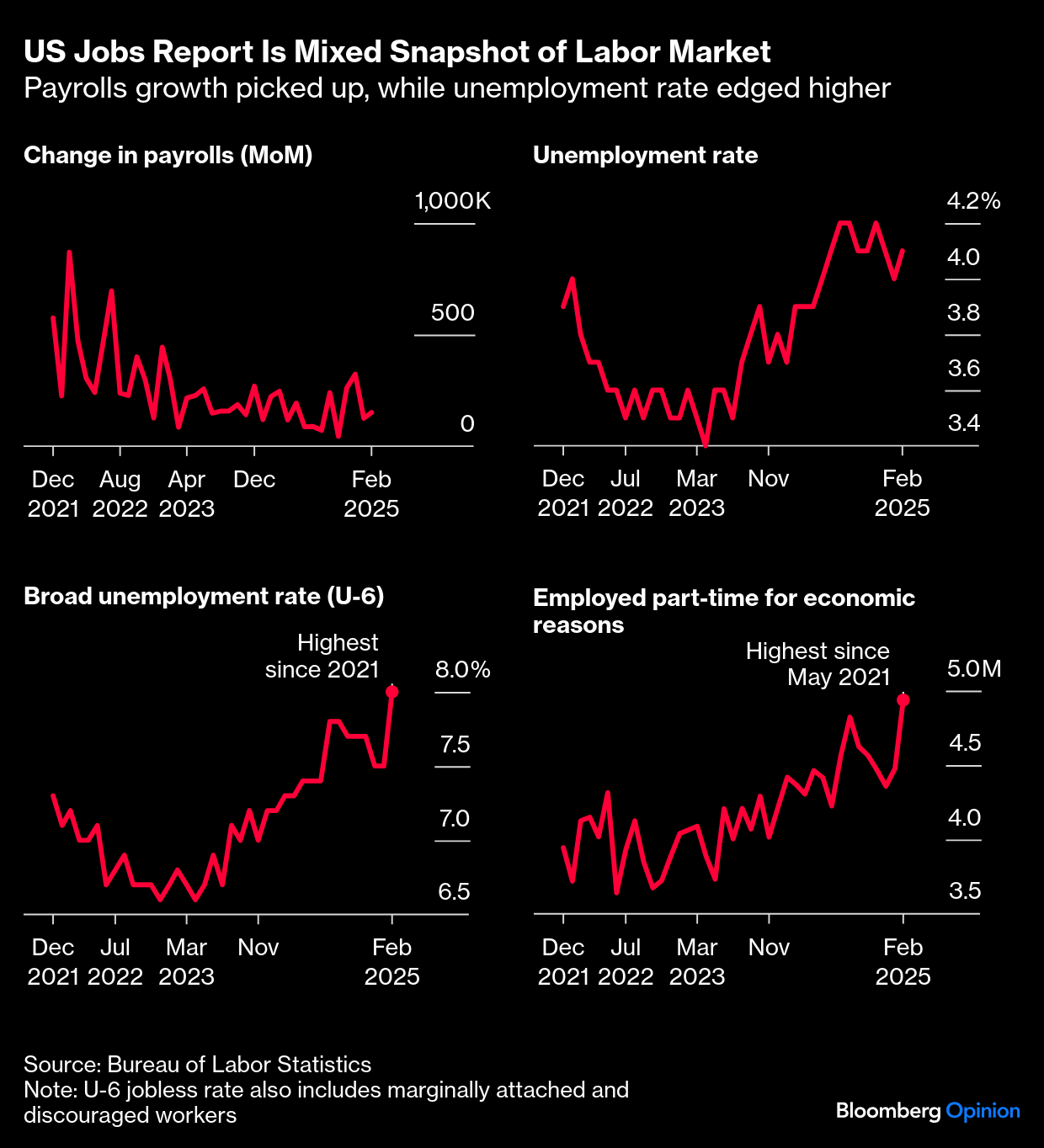

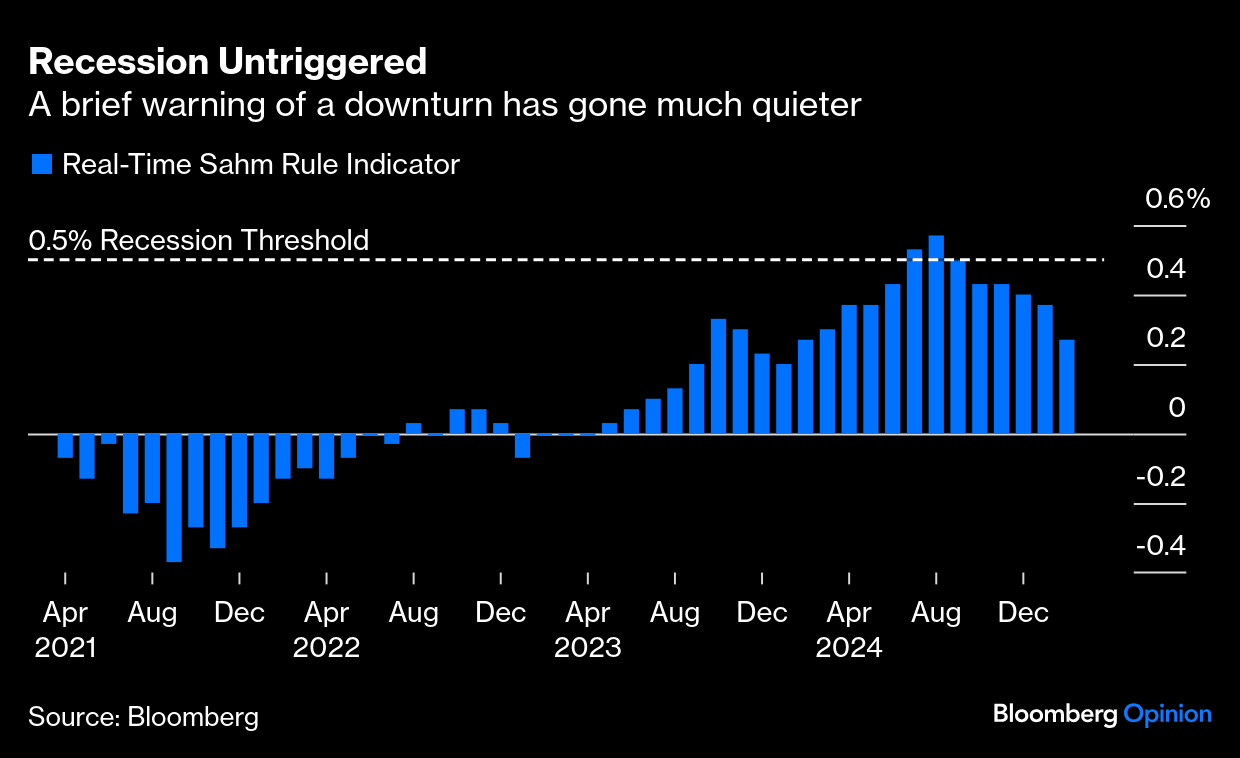

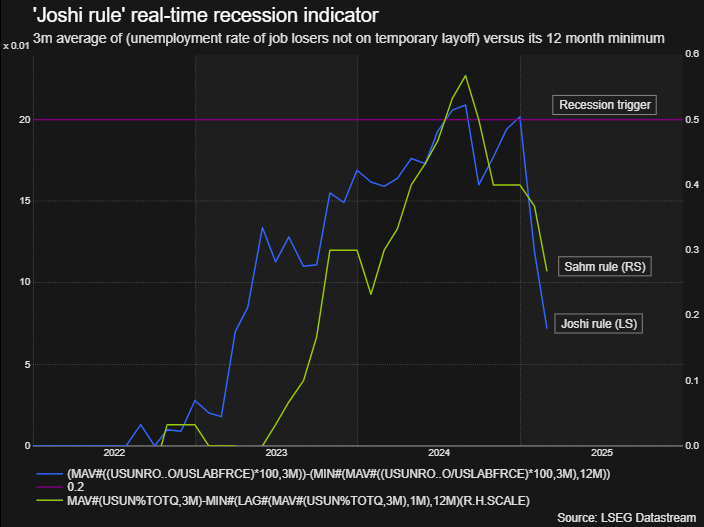

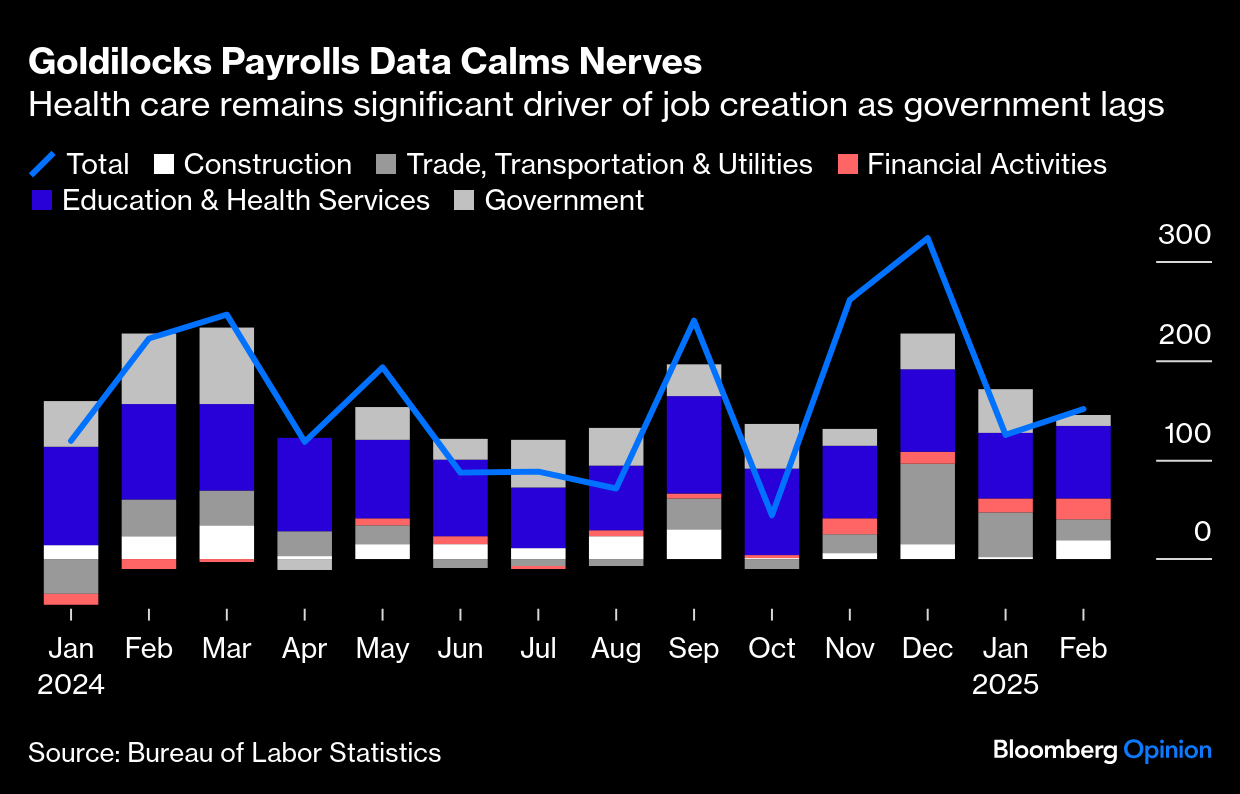

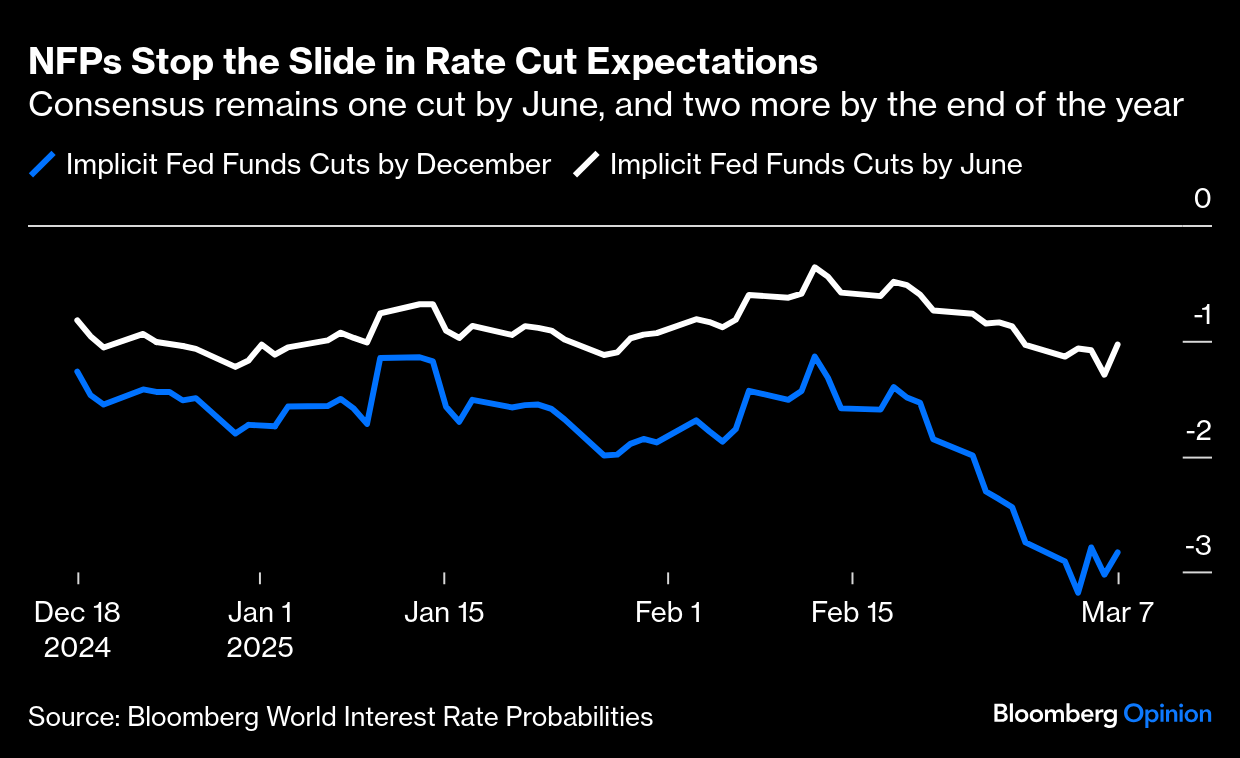

| Shibboleths are shattering in Europe. In the last week, it's abandoned assumptions about its defense and how it runs fiscal policy that had endured for a lifetime. Amid that drama, the European Central Bank cut target rates by 25 basis points and announced that its monetary policy had become "meaningfully less restrictive." If this sounds boring compared to the other volcanic European shifts, that's because it is. But there's still a change. The ECB's own confrontation with Europe's shifting tectonic plates will come soon. Previously, the ECB had said that policy was "restrictive," so this was a shift. But it wasn't so much a change of direction as what President Christine Lagarde called an "evolution." If it's less restrictive, then it's closer to the point where the ECB can stop cutting rates. As it's still restrictive, however, the bias remains toward cuts. That's reflected in market expectations, which see more cuts but now project the target rate to be 2.0% by year-end: The question is what happens next. Barring political mishaps over the next two weeks, German fiscal policy is about to get as loose as it's been in generations, while the European Union is thrashing out massive new investment in defense. The EU must also contemplate the likely imminent imposition of tariffs by the US. This would be directly negative for growth, while retaliation would put upward pressure on inflation. With the exception of one abstention, this decision was unanimous. The euro-zone economy is weak, the defense spending and tariffs are still matters of conjecture, and it made total sense to cut. But as my Bloomberg colleagues swiftly pointed out, the next meeting in April will be different, and conflict is very likely. Should they respond to loose fiscal policy with tighter money? Already, Isabel Schnabel, regarded as one of the most hawkish members of the ECB's governing council, has set out her stall in Handelsblatt. It's not clear where r* — the neutral rate of interest that is neither contractionary nor expansive — is at any one time, but the hawks can argue that the big splurge of spending ahead is bound to move it upward. That means fewer cuts. Another variable is the bond market, which sets longer-term rates. Germany's new fiscal dawn has brought the yield on the 10-year German bund up by 50 basis points in a week, as traders attempt to discount the extra borrowing. This tightens financial conditions. But there's little or no fear that this will be a German "Liz Truss incident." When Britain' s former prime minister shocked the market with a radical new fiscal policy, a bond market revolt soon forced her to abandon tax cuts and resign. Bund yields are far lower than gilt yields were then, though at their highest since the outbreak of the euro-zone debt crisis in 2010:  However, the last 15 years, which for a time featured negative nominal rates, are regarded as an anomaly. Bund yields at historically normal levels could be treated as a sign that the extraordinary conditions are over. The market has effectively been telling the German government that it's free to borrow more if it likes. There's a widespread belief that Germany has been too frugal for its own good and that it will be a better bet to repay debt if it borrows more. Indeed, there's also a way in which the structure of the euro zone endowed Germany with an exorbitant privilege that it refused to use until now. That term refers to the advantage that the US gains from the dollar's reserve currency status. Similarly, the euro zone meant that when investors wanted to buy bonds in Europe, bunds were plainly safer than anyone else, and so Germany could borrow at a lower rate. While each country's bonds had been in a sense risk-free in their local currency, the creation of the euro made Germany's debt safer. With Germany borrowing more, the risk must be that other European borrowers will be crowded out. Special Europe-wide bonds to raise money for defense would also be safer and tend to force other euro-zone members to pay more for their debt. At present, the spreads over bunds at which other European bonds trade are quite narrow — although the rise in French spreads is disquieting: Now that Germany intends to exercise its privilege, and Europe intends to start borrowing for defense in its own right, the risk is that some euro-zone countries are going to find it much more expensive to borrow. The ECB has to start thinking what it will do about that, too. Is the US really sliding into a recession? Such fears have plainly taken hold in recent weeks, and February's jobs report was the latest test to come back from the lab. It at least suggests the patient doesn't have much to worry about. That won't mean that we can ignore worrying signs that cause genuine concern, such as softening consumer confidence, mass federal job layoffs, economic policy uncertainty, and rising inflation expectations. But the report suggests that the infections that might lead to a recession diagnosis remain at the latency stage, even if all the main measures are gently trending in the wrong direction:  The biggest market concern is about the chance of a recession. Unemployment tends to rise slowly and then surge. The Sahm Rule, named for Bloomberg Opinion colleague Claudia Sahm, holds that when the unemployment rate is more than a half percentage point above its low for the previous year, a recession ensues. That threshold was triggered last year, contributing to a scare. Now, it suggests little reason to worry: A revision of the Sahm Rule by BCA Research's Dhaval Joshi (dubbed the Joshi Rule) looks at the three-month moving average of the unemployment rate of "job losers not on temporary layoff," or "bad" unemployment. When it rises by 0.2% from its low during the previous 12 months, it means a recession is coming. This measure, as Joshi shows, has eased even more dramatically: This helps explain why markets generally responded with muted relief to the jobs numbers. But there were warning signs in more long-term unemployed people, fewer federal workers, and an increase in those working part-time for economic reasons. People working multiple jobs reached a record of nearly 8.9 million. But overall, nonfarm payrolls were up 151,000 in February following a downward revision to the prior month, continuing a "Goldilocks" trend in which jobs rise, but not too fast: The headline fell short of estimates, but that could be attributed to weather disruptions, and to job cuts from Elon Musk's Department of Government Efficiency. Negligible revisions for the previous two months were also reassuring. But the numbers didn't reverse the growing concern in recent weeks about a recession. This is how the forecast by Bloomberg's World Interest Rate Probabilities, derived from futures, has moved since Jan. 2: The change in interest rate expectations is unmissable. However, the latest jobs report seemed to arrest the trend: For rates to fall this much, the Fed will need to be be convinced that employment faces a significant deterioration. Oxford Economics' Nancy Vanden Houten argues that this report wasn't enough to move the Fed off the sidelines. Glenmede Research's Jason Pride adds: Given uncertainties regarding trade policy, June may be a live meeting for them to consider restarting the rate-cut process if they judge a material impact on aggregate demand. The base case is now ~3 rate cuts this year, but those expectations may be volatile until the size and scope of trade policy come into greater focus.

The impending fork in the road for the Fed makes for an interesting watch. Bank of America's Shruti Mishra argues the disappointing household survey and solid wage growth are consistent with mild stagflation. With inflation already above target, however, Mishra argues that the Fed won't cut further — although markets may worry about the risk that if it's too slow to act, that may exacerbate the eventual downturn. —Richard Abbey A couple of points from my well-timed trip to Frankfurt. First, those of us who speak English as a mother tongue have an exorbitant privilege of our own. It's the lingua franca of finance and of Europe. I went to an International Women's Day event at the ECB, with six senior ECB bankers on stage. None spoke English as a first language; the only remaining EU countries with English as an official language are Ireland and Malta. And yet that was the language they used. A few years ago, I saw Jean-Claude Trichet, a former head of the ECB, interview Lagarde on a stage. Both are French. They spoke in English. I'm not saying this is unfair or that it doesn't make sense. In smaller European countries, English is the way to communicate with foreigners; they won't know Finnish, or Estonian, but they probably speak some English. But years after Brexit, and with the US apparently on the verge of abandoning the continent, it was bizarre to see such conversations in the very heart of Europe. We English-speakers should know we're lucky.  A concrete path at the former site of a train ramp from where Jews where deported. Photographer: Frank Rumpenhorst/DPA/AFP/Getty Second, it was the first time I had ever visited the ECB's spectacular glass-tower headquarters on the banks of the Main, which opened in 2015. I didn't know it was built directly on top of Frankfurt's old wholesale market hall, a startling piece of 1920s architecture. That market gained ever-lasting notoriety once the Nazis used it to herd Frankfurt's Jews together before putting them on to the conveniently adjoining railway. The ECB solved a problem for the city by taking over the building, preserving it and making it a memorial. It's a moving place to visit, and I'm very grateful for the opportunity to do so. Much like the buildings on the Mall in Washington, the ECB is a self-conscious attempt to construct a new institution. It's inspiring, and the fact that it's built on and commemorates land where some of the worst crimes of the century took place is a potent reminder of why the European project matters. The ECB has constructed a moving sign of aspiration — but also a reminder that Europe hasn't managed to create many other common institutions of similar strength. There may well soon be a need for more such buildings to house different shared institutions. Some long-form reading on the extraordinary shift in US foreign policy. I don't necessarily agree with all of these pieces, but they're interesting and worth your time: Jeffrey Sachs' speech to the EU parliament deservedly caused a stir; Nick Cohen's substack offers a trenchant attack; St. Andrews University professor Phillips O'Brien offers a two-part broadside here and here; Yanis Varoufakis attacks European rearmament in Project Syndicate; Adam Tooze explains why the German fiscal deal isn't done yet on Substack; and if you'd prefer to listen, try Helen Thompson and Dan Snow on the subject. There's a lot to discuss. Enjoy the week ahead everyone. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: - Allison Schrager: The Free-Market Conservative Is a Vanishing Breed

- Hal Brands: Aiding Ukraine Has Been a Great Investment for the US

- Patricia Lopez: This Tariff Seesaw Is Already Hurting US States

Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN . Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment