- Tariffs on Mexico are off again, for another month; tariff uncertainty remains and it's damaging;

- China's investors are betting on a big stimulus again, and the stock market is back;

- Beating the market: Yet more evidence, if you needed it, that it's really difficult;

- AND: More music for the panic button

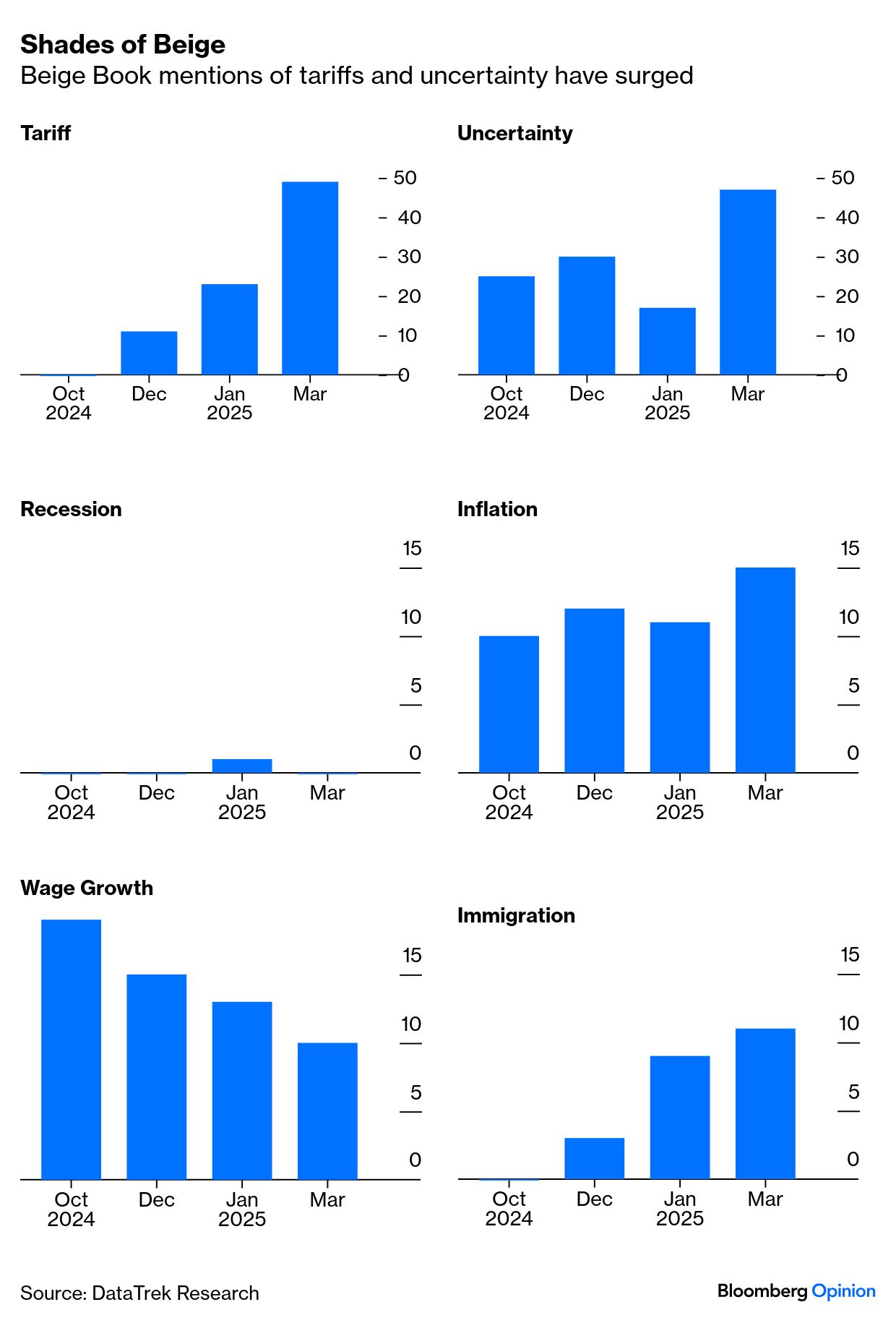

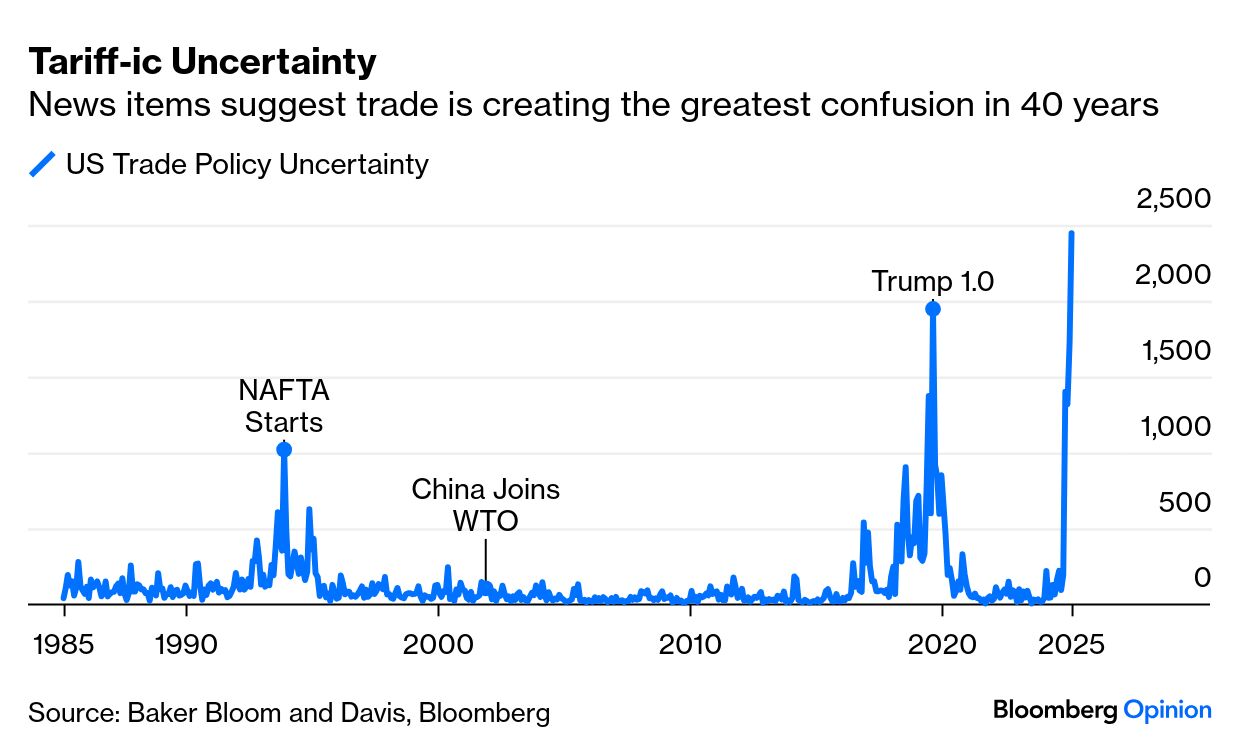

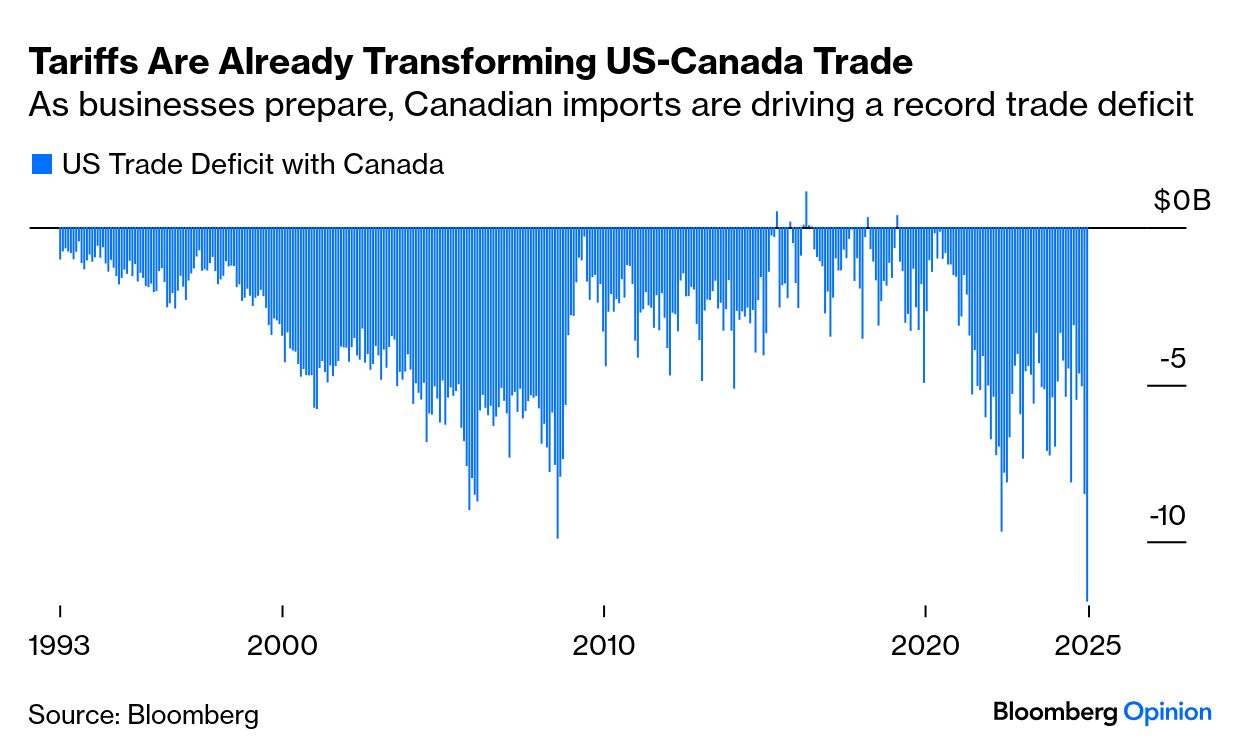

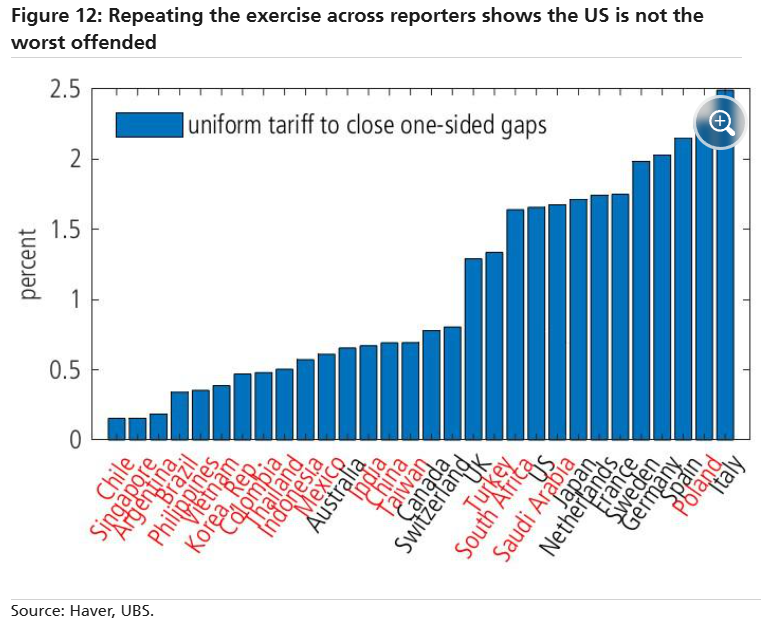

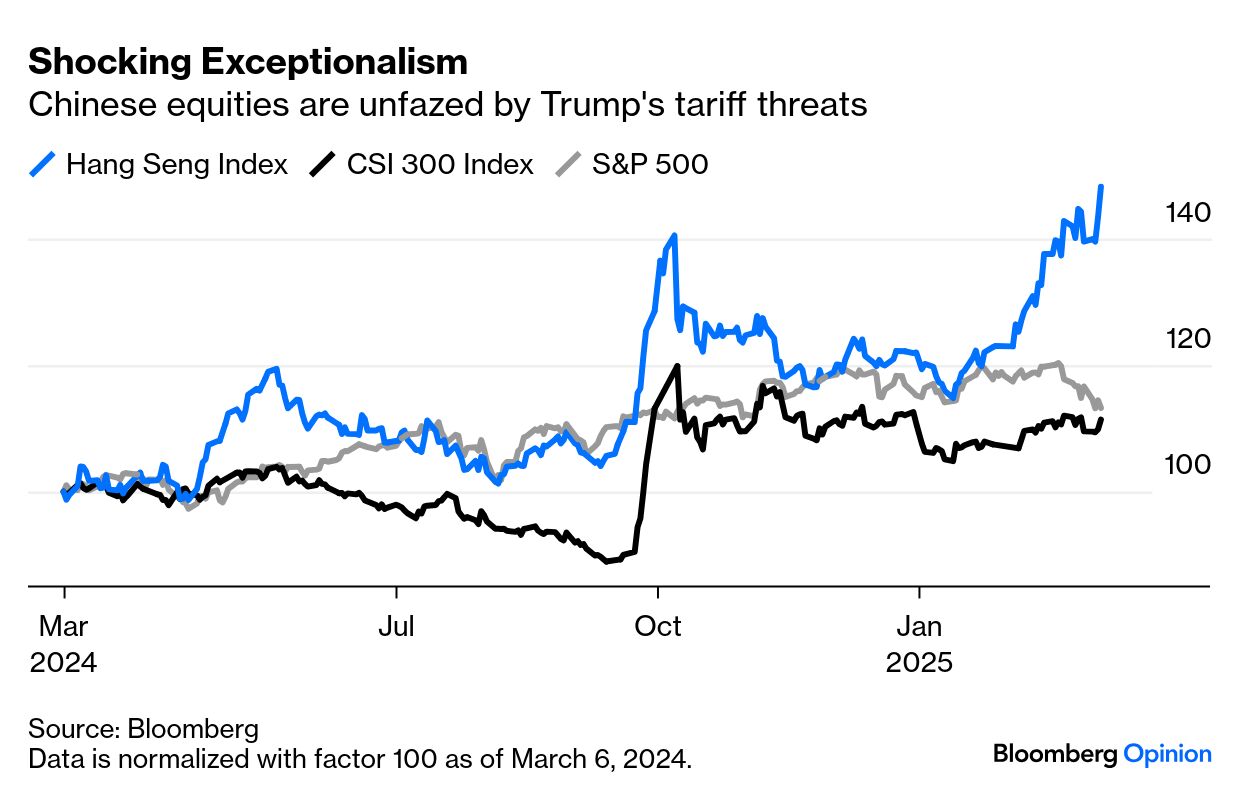

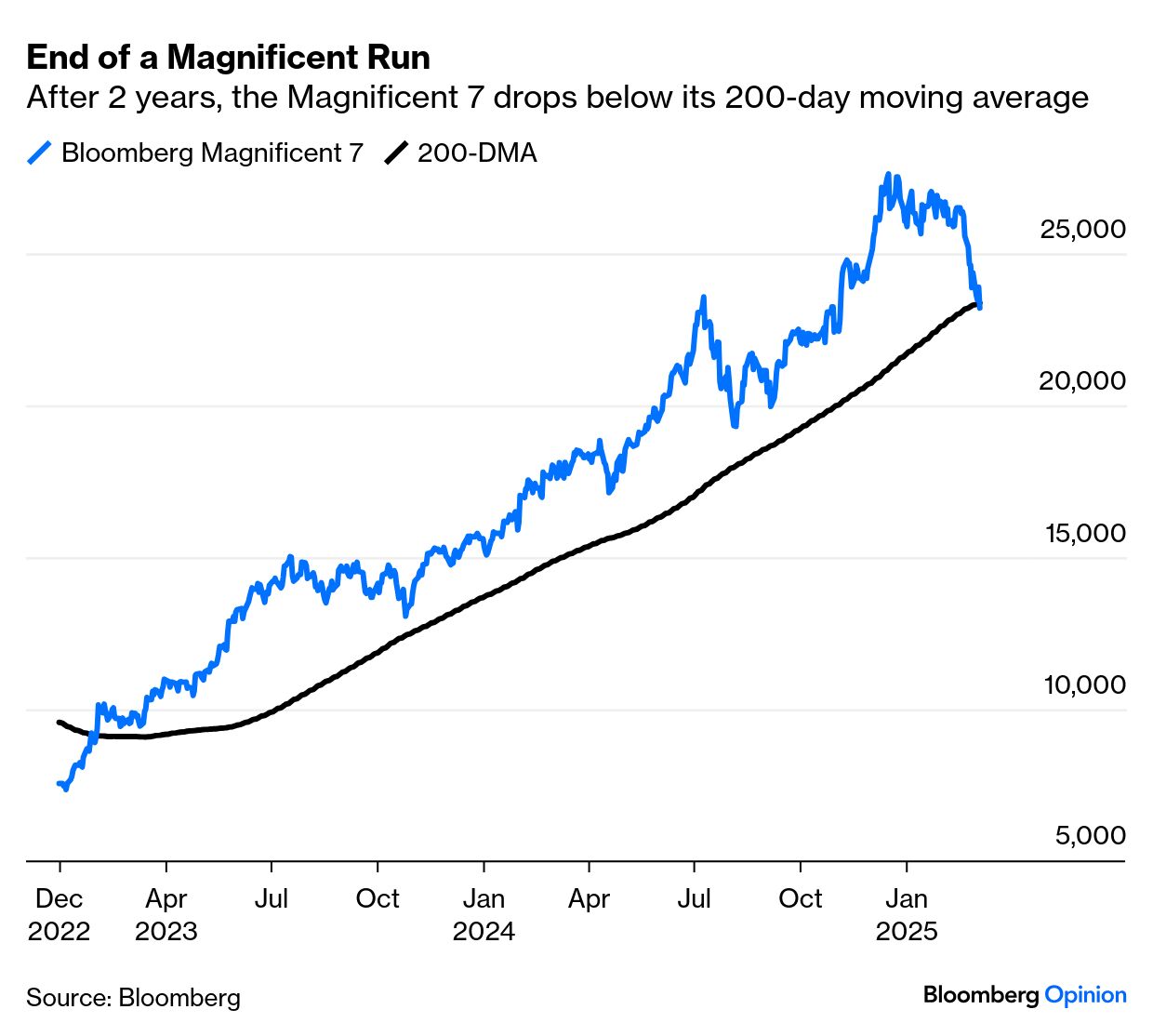

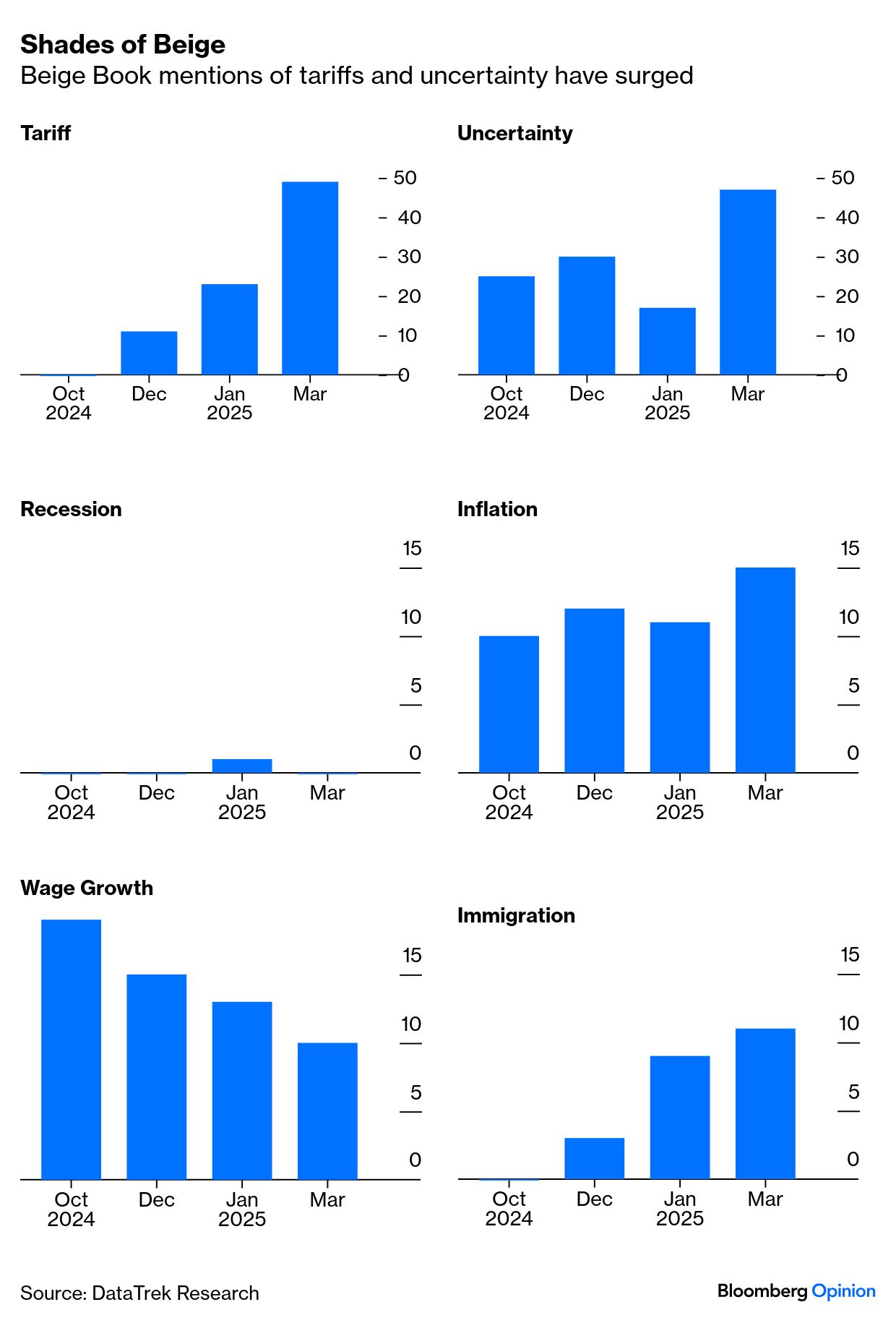

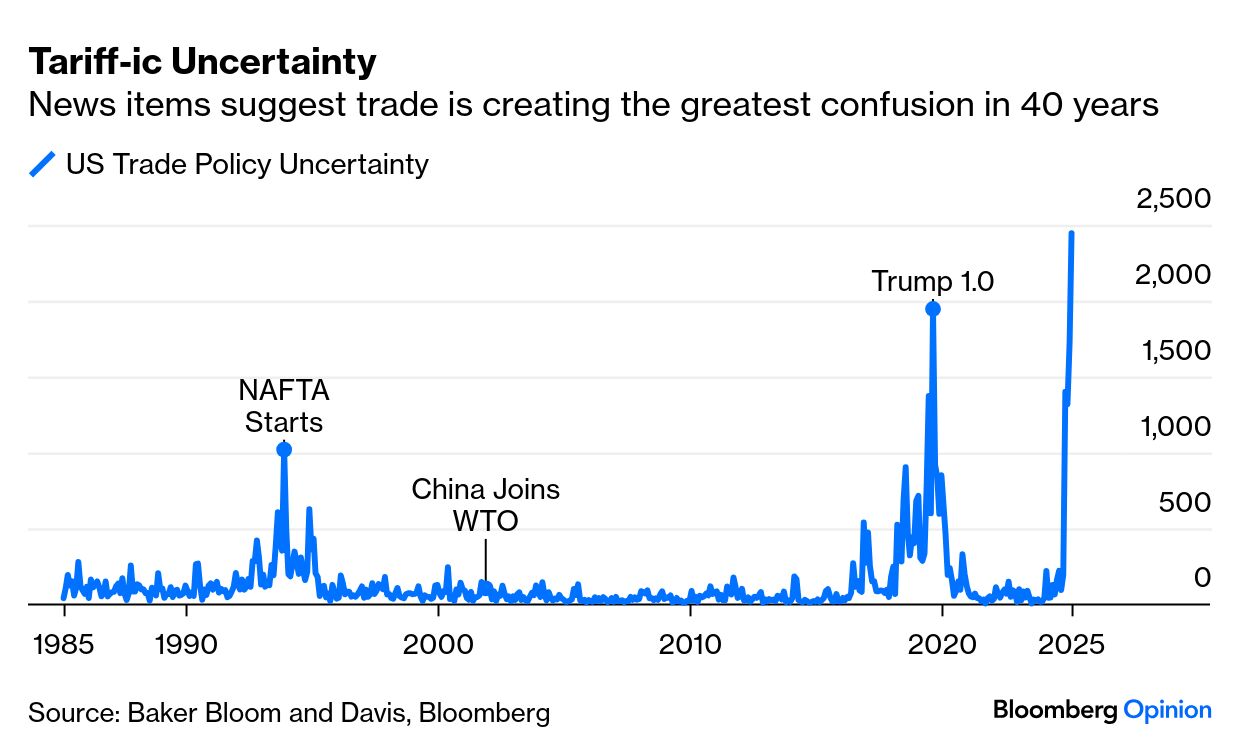

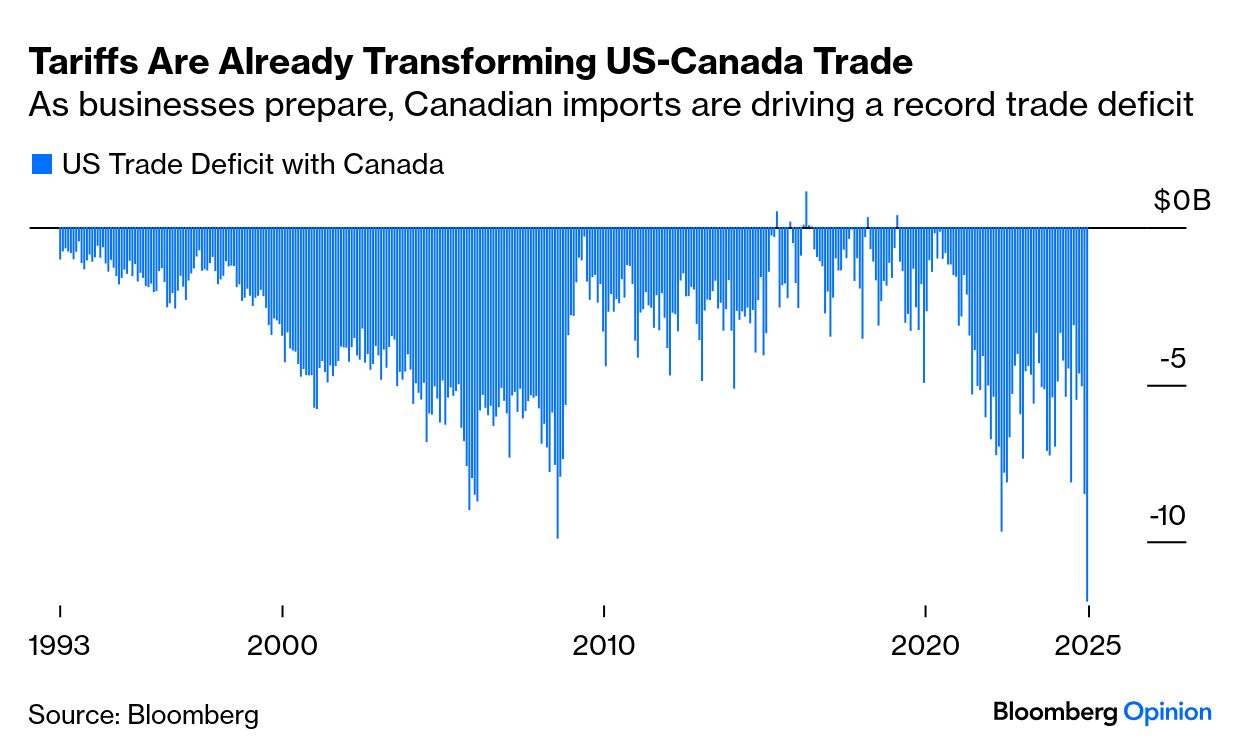

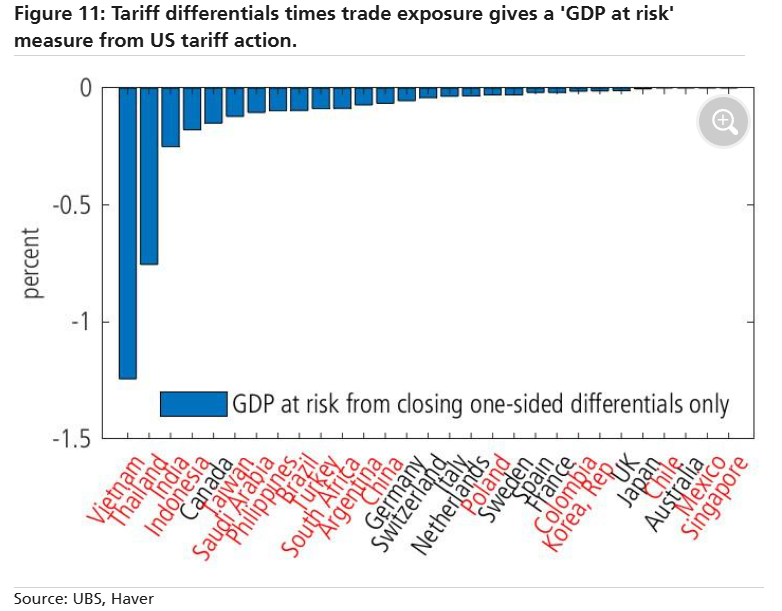

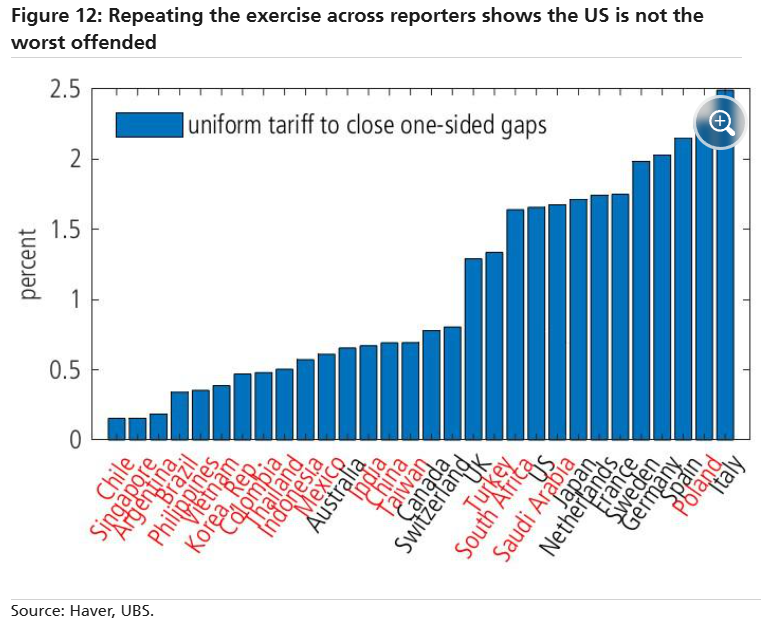

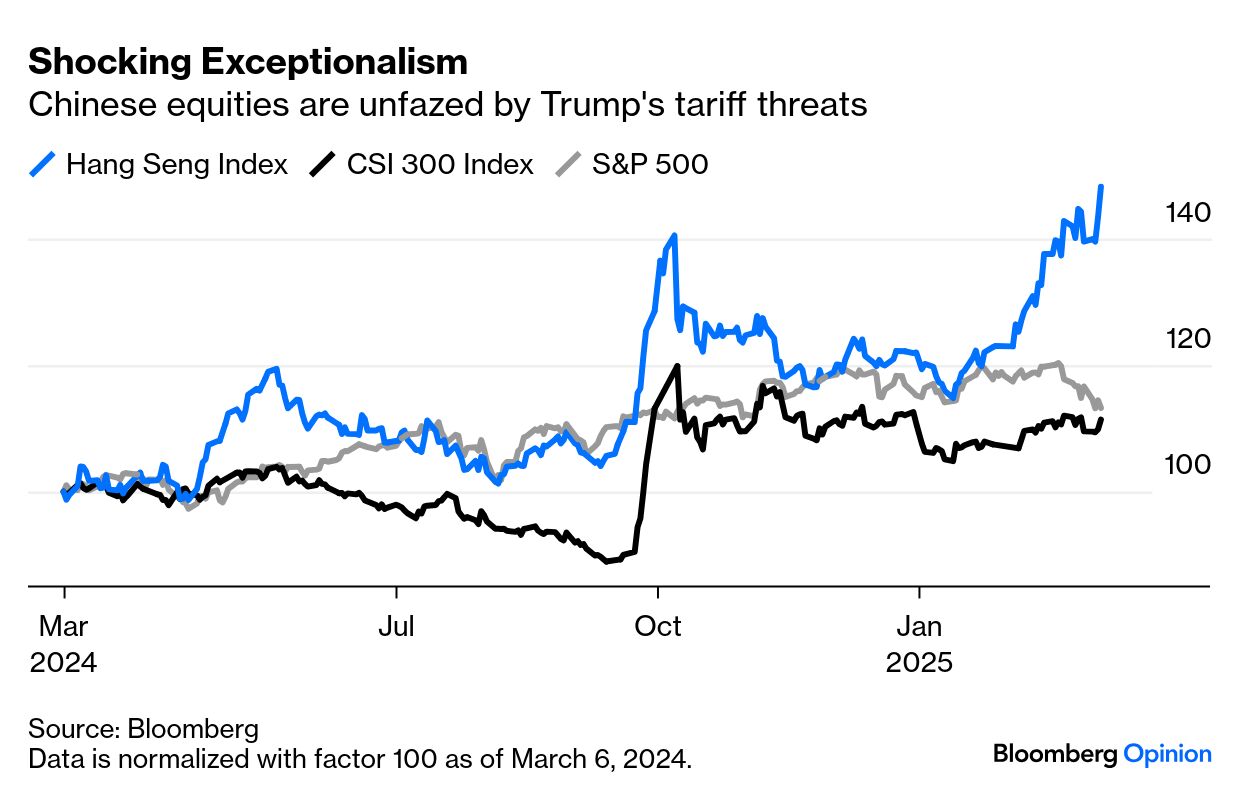

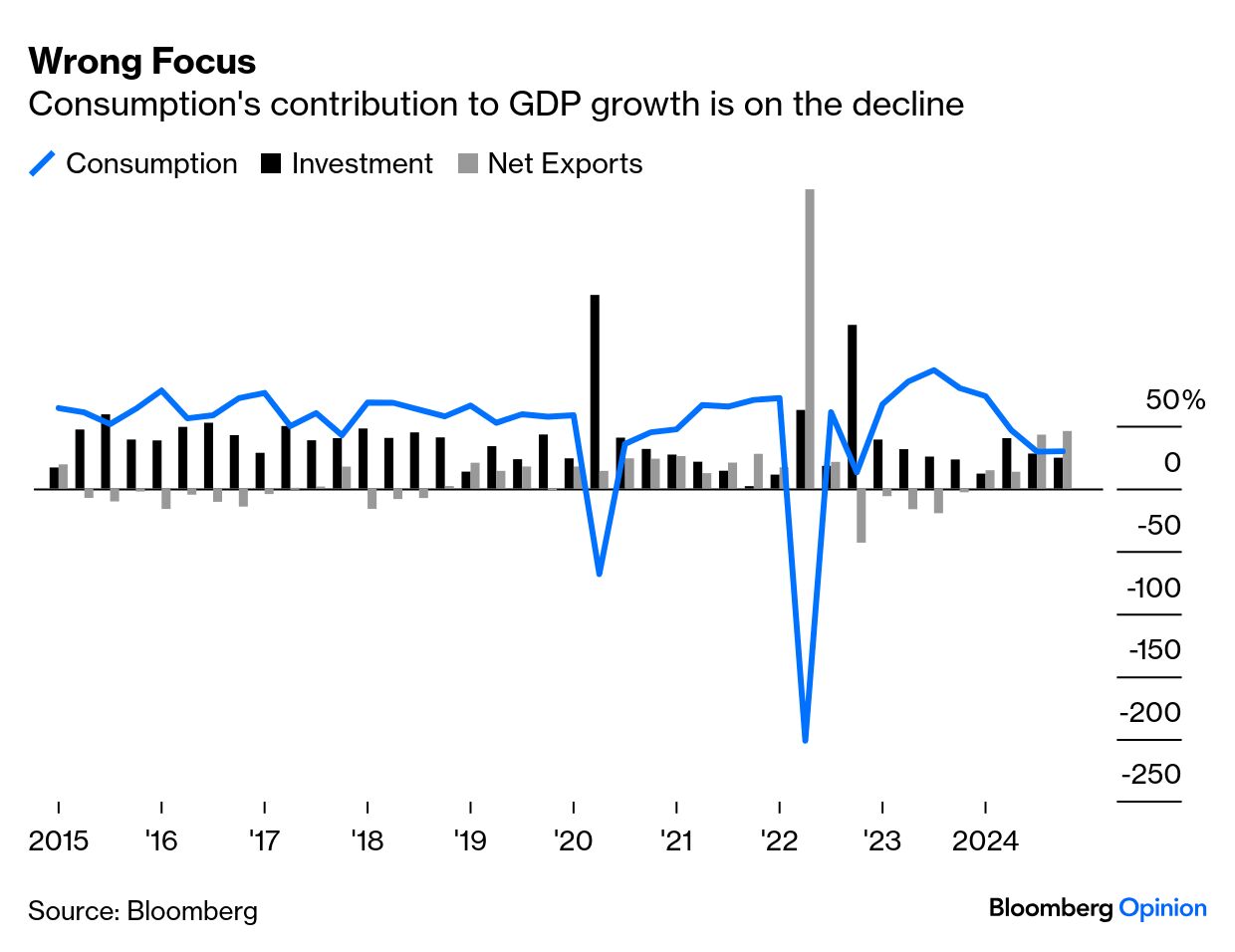

Paraphrasing FDR, there is an argument that we have nothing to fear from tariffs, save tariff fear itself. There are arguments that the cost might not be that high, but forecasting is maddeningly difficult because US policy is so inconsistent. Thursday, the US lifted the 25% tariffs on Mexico and Canada three days after it imposed them. This was what many wanted to hear, but amped up the uncertainty and volatility surrounding trade policy. The cost of tariff uncertainty is growing very visible, most clearly in a continuing sell-off for US stocks, which has now left the Nasdaq Composite down more than 10% from its recent peak (the popular definition of a "correction"). The Bloomberg Magnificent 7 index, including the dominant tech groups, is down 16%, and has just dropped below its 200-day moving average for the first time in more than two years: The latest edition of the Federal Reserve's Beige Book, its qualitative collection of anecdotes garnered by regional branches, was published this week and showed that the central banks' contacts were talking about tariffs far more than they had in December (when the election result was known). Virtually nobody is talking about recession. The data in this chart counts the number of mentions for each word, compiled by DataTrek Research:  That's strong prima facie evidence that tariffs are causing worry, and may already be changing executives' behavior. Moreover, the Baker Bloom and Davis index of trade policy uncertainty, derived from analysis of media mentions, has just spiked to the highest in the 40 years since its inception. Current anxiety dwarfs the concerns that people had as the original Nafta treaty was coming into effect, or during the first Trump administration. China's entry to the World Trade Organization, with hindsight by far the most significant trade change in this era, didn't register:  Meanwhile, when businesses have a clear idea that tariffs are about to be levied on goods they want to buy, they are bringing purchases forward and stockpiling untariffed goods. This was wholly predictable, and helps to explain why the latest US trade deficit, published Thursday, was the highest on record. That had much to do with the rush to send gold bullion to the US, which has little effect on the real economy. However, the spectacular widening of the US trade deficit with Canada shows that businesses are already taking evasive action. Canada is now in the eye of the tariff storm, when only recently many had assumed that it would be exempt. That's led to a remarkable buying spree as Americans stockpile Canadian goods:  As tariff proposals generate this upheaval, lobbying of the administration to change course has gained momentum. The plan is now for a reciprocal tariff system in which all importing levies will be matched one-for-one by tariffs on imports of the same products to the US. It's growing clearer that the potential revenue to be gained is much less than had been thought, largely because the US has less cause for grievance than it believes. UBS Group AG conducted a massive research exercise of the trade between the US and 30 of its largest trading partners, analyzing 96 categories and 86,000 product/partner pairs. Reciprocal tariffs wouldn't raise that much money, or have that big an economic impact. UBS estimates that lifting US tariffs to the level of its partners would only equate to a weighted average increase of 1.65 percentage points (0.8 for developed markets and 2.2 for emerging), and generate only about $18 billion to $32 billion in annual revenue. Reciprocity will often mean raising tariffs on goods that the US doesn't import anyway. If a trade partner is exporting a product, UBS argues, it's unlikely to be importing it. That's the whole point of comparative advantage. So this is a complicated nightmare that would significantly affect a number of countries. The biggest losers would be in Asia, led by Vietnam. Mexico, which has long had reciprocal arrangements under its trade treaty with the US, would barely notice: The UBS exercise also reveals that the US is not particularly hard done by. The following chart shows the amount by which each country would need to raise tariffs to achieve reciprocity. Japan, and a number of European countries, would need to lift them by more than the US:  UBS's punch line is: "Closing tariff gaps at the product-trading partner level amounts in tariff terms to a blanket tariff increase of 1.65% by the US. This is roughly an order of magnitude smaller than the 10% blanket tariff that candidate Trump was threatening to impose on the world." So a reciprocal system, to be unveiled April 2, represents a major climbdown dealing with a problem that is not that serious. You can't easily argue that it's worth the uncertainty that it is creating. And if this is what indeed results, there's no need for stocks to sell off like this. The market is, however, sending a clear message that it wants clarity on tariffs, and that it would prefer to do without them altogether. The question, growing ever clearer, is whether the Trump administration will stand up to the market. Beijing 1, US Exceptionalism 0 | Trump's growing attack on Beijing's fragile economy may count as an own goal. The animal spirits aroused by China's September "whatever it takes" moment may be untamable. Or possibly both: The scenarios aren't mutually exclusive. Either way, Hong Kong's Hang Seng Index has surged to its highest in over three years, despite an increase of 20 percentage points in US tariffs since January. The mainland CSI 300 is also up by more than 25% since the stimulus talk started in September. It has recently traded sideways as geopolitical tensions simmer, but its ability to weather the economic uncertainty is impressive. Over the last 12 months, it's matched the S&P 500:  What's going on? As Gavekal Research's Thomas Gatley points out, the market may be digesting the contrast between China's government, which confirmed a sizable fiscal stimulus for this year, and the US, whose policies seem designed to disrupt growth and raise prices. Possibly by good fortune, Chinese officials were able to parse the potential impact of Trump's tariffs before they presented their economic plans to the National People's Congress, the annual legislative session. Gatley notes that the 2025 budget deficit — expected to rise to 4%, a 30-year-high — confirmed hopes for stronger stimulus and buoyed Chinese equities. China watchers know this feeling. While Beijing's effort to steer out of the real estate-induced slump has been slower than hoped, the commitment to growth is steadfast. The Communist Party is confident of achieving "about 5%" growth in 2025 — even if there's a full-scale US trade war. The growth target increases the urgency for a belated package of measures to shore up domestic consumption, whose contribution to GDP growth has been falling: Premier Li Qiang told this week's NPC that stimulating domestic demand is the highest economic priority. Counting on exports is no longer viable, as other countries are ready to throw Beijing under the bus to placate Trump. How soon can consumption firepower come on stream? Bloomberg Opinion colleague Shuli Ren describes it as a "low-hanging fruit;" consumption is only about 40% of the economy, versus 55% in culturally frugal Japan and Germany, and 63% in Brazil. Chinese officials know more is required to head off the impact of a trade war. The finance minister, Lan Fo'an, stated Thursday that they have ample fiscal policy tools and space to respond to possible domestic and external challenges. This followed People's Bank of China Governor Pan Gongsheng's remarks that it would cut interest rates and lower banks' reserve requirement ratio at "an appropriate time." The economy's best-case scenario would still be to avoid a trade war. Bank of Singapore's Mansoor Mohi-uddin argues that China's restrained response to US tariff aggression to date signals that Beijing is willing to negotiate with Washington and wants to avoid escalating tensions further. He estimates the 20% rise in US tariffs may shave up to 1% off China's GDP, cutting growth from 5% in 2024 to 4.2% this year. In a scenario where the US recalcitrance persists, Gavekal's Gatley suggests that China is positioning itself to weather the tariffs better than the US would. China could gain a relative economic advantage: And an even bigger diplomatic advantage: Trump's friendliness with Russia is unlikely to draw it away from China but is eroding US influence in Europe. If the trade war with Canada and Mexico drags on, US inflation heads up, and growth drops further, that gamble that the US will be the bigger victim will likely prove correct. That will probably also play out in relative stock market performance.

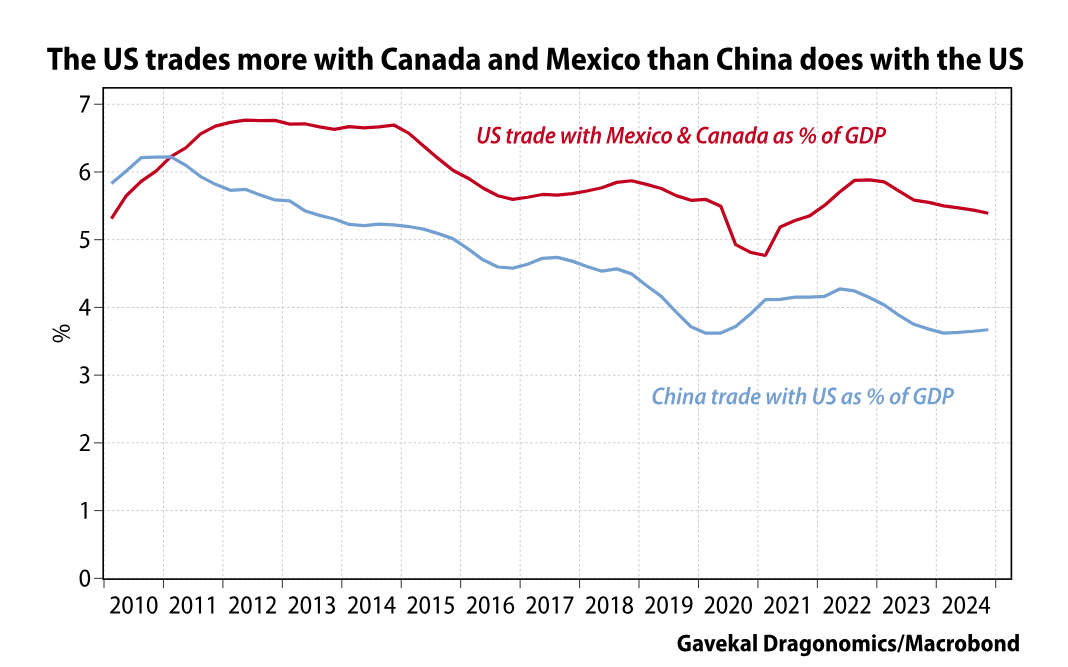

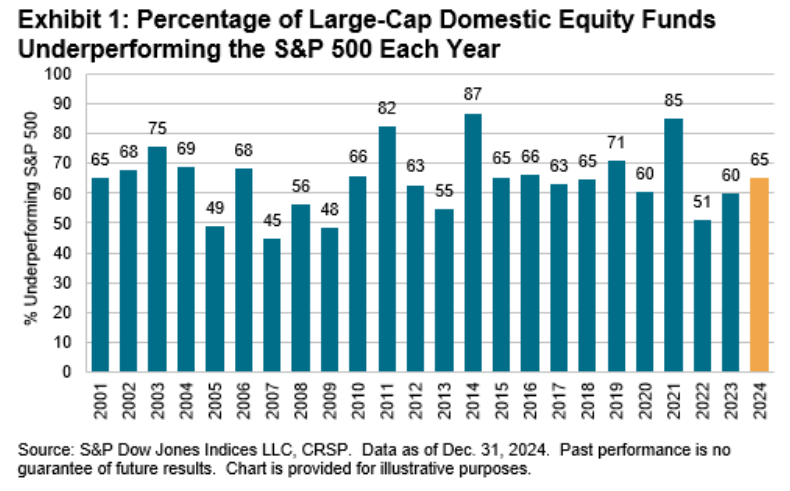

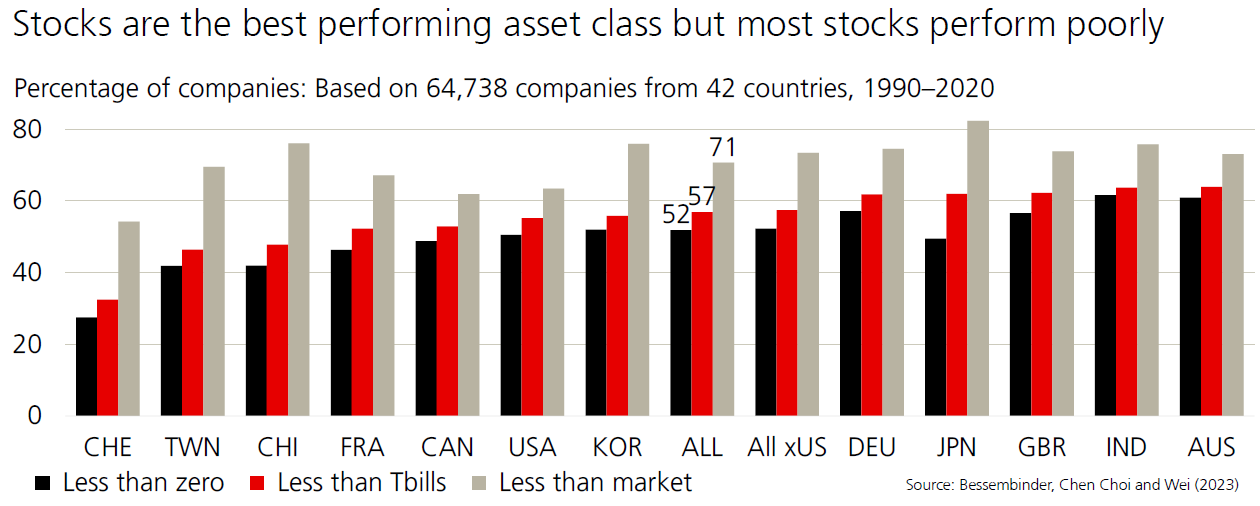

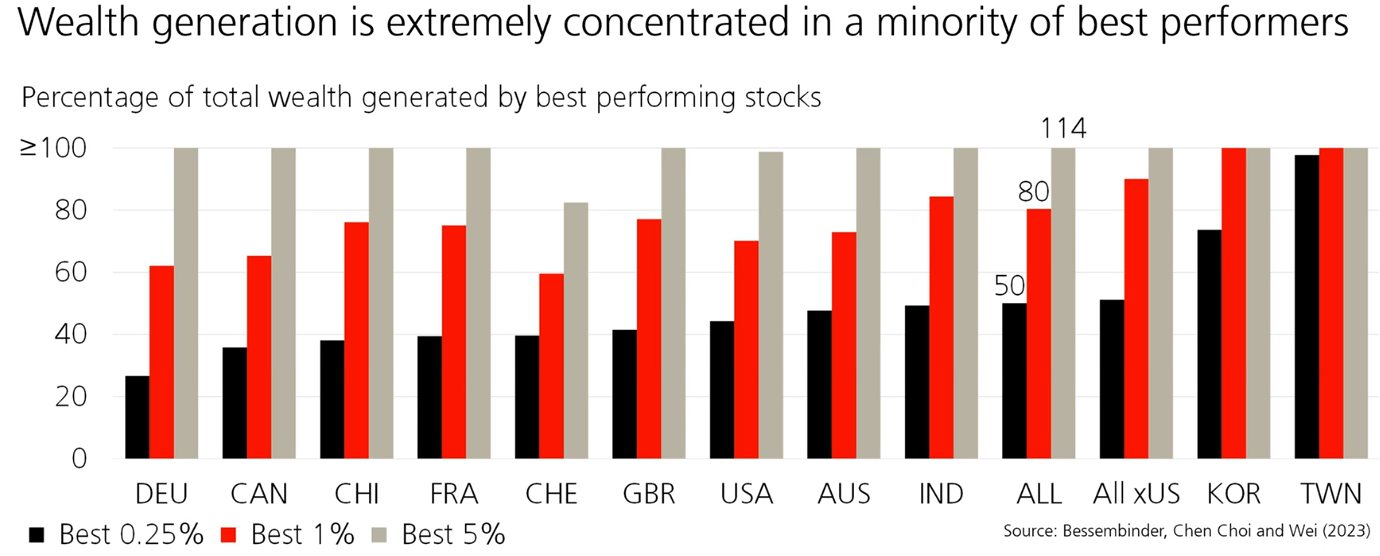

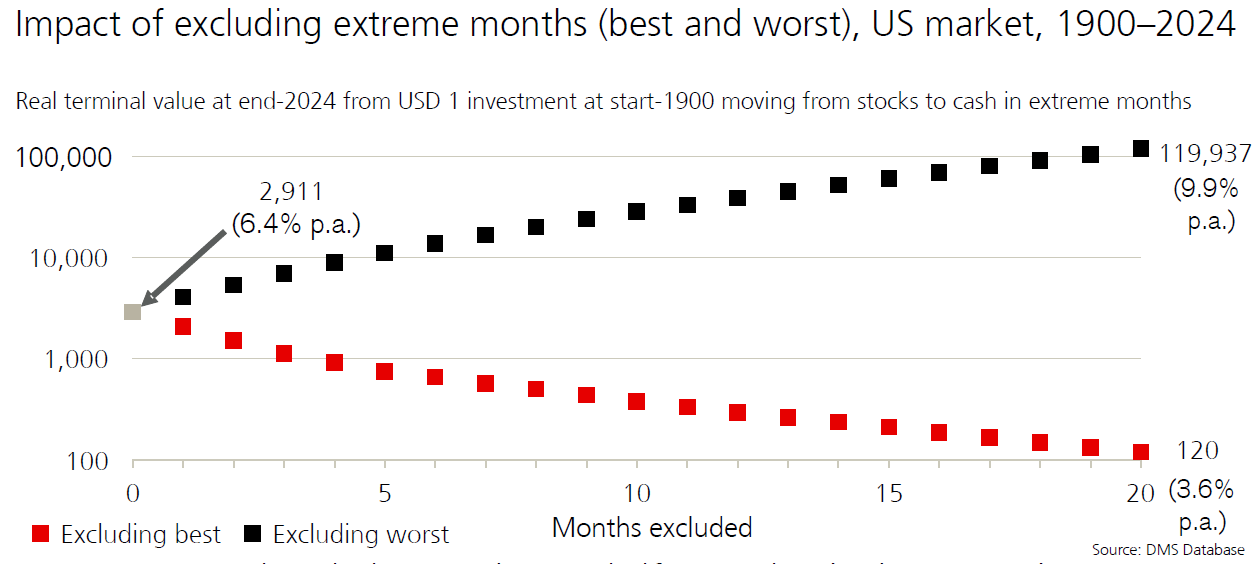

This Gavekal chart shows US exports as a proportion of China's GDP are declining: As uncomfortable as the uncertainty may be, it's an incentive to address long-standing issues that require significant commitments. That's happened in an extraordinary way in Germany, and China is attempting the same thing. Whether these overdue policies achieve their intended outcomes is another matter — but equity investors plainly believe this is a better option than inaction. — Richard Abbey Should we even try to beat the market? Standard & Poor's have just published their regular SPIVA survey of how US mutual funds have fared in their attempt to outperform the S&P 500, and for the 15th year in a row, most have failed to do so: There's an argument for this from efficient markets theory. In total, funds will roughly hold the entire index between them. As they need to charge a fee for their services, which comes out of their return, it is only natural that a majority will lag the index. That said, usually a good third of funds do manage to beat the index each year, even after costs. In the annual Global Investment Returns Yearbook, academics Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton, get into more profound reasons why the odds are stacked against active equity managers, showing that in the three decades from 1990 to 2020, most stocks globally (52%) lost money, while 71% failed to match the market. So it's very easy to lag: Further, there are very few big winners. In most markets, the best 5% of stocks account for substantially 100% of returns: So the returns for picking shares correctly would be fantastic. That's why people try it. But the odds are that you won't in fact beat the market. Similar arguments apply to timing. Stocks tend to advance steadily and decline in a hurry. Since 1900, if you had been out of the market for only the worst 20 months, and stayed invested for the other 1,480, your annualized return on US stocks would have been 9.9%, rather than the 6.4% for those who stayed in throughout. But there would also have been a penalty for missing the best months. Cut out just the best 20 months out of those 125 years would have reduced annualized returns to 3.8%: But you need to get it right. The figures also show quite clearly that there's a very serious chance to get this wrong. Anu Ganti, S&P Dow Jones Indices' head of US index investment strategy, argued that these added to other difficulties for active managers: If you talk about the evolution of indexing there's a couple of headwinds that we've seen that haven't really changed over the past couple of decades. One is just the cost. The other is just a positive skewness of equity returns. Over the long term, outperformance for most equity markets tends to come from a handful of stocks. It really makes the case for diversification.

Further, most stocks are now held by professional managers, making it far harder to beat the market. Marsh of the London Business School, one of the yearbook's authors, summed up that investors should be well diversified "unless they have reason to believe they are very good stockpickers." (Few of us are.) This justifies the lengths some hedge funds go to in their search for concentrated bets. If you really can find someone who's good at stock-picking or market timing, it's worth paying them for their services. It also confirms that most of us should be invested passively. — John Authers and Richard Abbey Some classical music to play when you hit the panic button. Try the adagio from Beethoven's Fifth Piano Concerto ("The Emperor"), the andante from Mozart's 40th symphony, As Steals the Morn by Handel, Il s'en va loin de la terre from Berlioz's L'Enfance du Christ, or Senza Mamma from Puccini's Suor Angelica. For something more contemporary, try Gerry Rafferty's Baker Street, Mike Oldfield's 1973 classic Tubular Bells or perhaps the more acoustic Tubular Bells II, which came out 20 years later. Please survive non-farm payrolls, which we didn't have room to mention, and have a great weekend everyone. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN . Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment