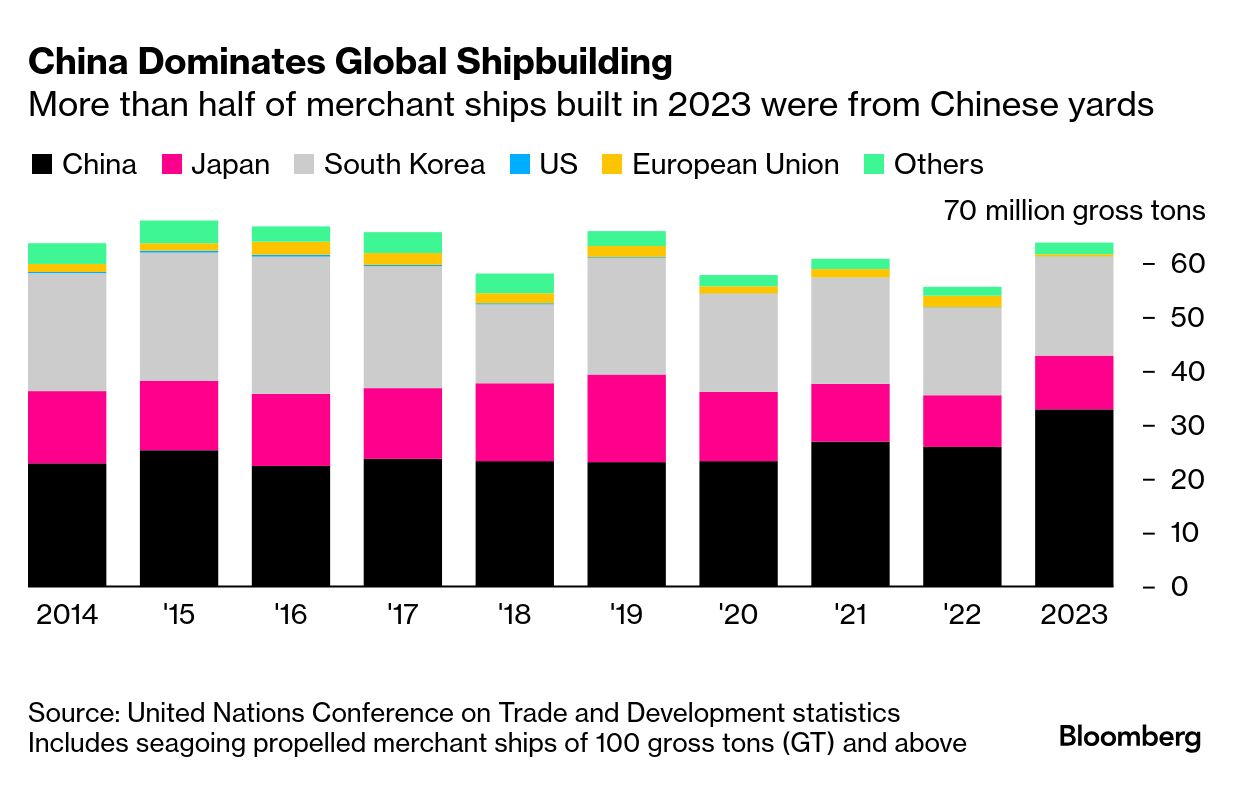

| China's "century of humiliation," as President Xi Jinping likes to call it, arrived by sea, with foreign merchant vessels backed by naval assets. More than one and a half centuries before China joined the World Trade Organization, the British forced it into the global trading system in a highly subjugated form. When neighbor Japan was presented with something similar in the 1850s, via an American ultimatum presented by Commodore Matthew Perry, Japanese modernizers, viewing the China experience, quickly understood the importance of controlling your own maritime trade. While China trading was dominated by Western "hongs" such as Jardine Matheson, Japan built its own trading houses — which are still thriving today (Warren Buffett is a big fan.) China in turn had Japan's example when it kicked off its own economic modernization in the aftermath of the ruinous decades under Mao Zedong. In maritime infrastructure, Beijing took Tokyo's game plan and supercharged it. Since the 1990s, China has become the world's dominant shipbuilder, has one of the biggest shipping firms in Cosco Shipping plus the top port builder in China Communications Construction. Now, the US has identified China's maritime preeminence as a construct of its mercantalist industrial policy, as well as a potential geo-economic chokepoint. Following on a Biden administration investigation, the Trump administration in late February kicked off a potential escalating scale of fines for using China's commercial ships. The big question though is whether Washington is truly ready to spend the money to rebuild a capacity the US outsourced long ago. With President Donald Trump's incoming chief White House economist this week calling for an industrial policy putting national security at its core, this will be an area worth watching.  A Cosco ship at the Port of Long Beach, California, on Feb. 20. The US Trade Representative's office is proposing a levy of as much as $1 million to be charged when Chinese-built vessels enter a US port. Photographer: Kyle Grillot/Bloomberg This week in the New Economy | China's history of being exploited by Britain, the US and others provided a harsh lesson in the leverage offered by controlling maritime trade. Not only did foreign trading outfits benefit from so-called unequal treaties, their assets were protected by patrols up the Yangtze River by the Royal and US Navies — through deployments called the China Station and Yangtze Patrol. The equivalent would be Chinese gunboats patrolling the Mississippi River. Today, not only does China's Cosco handle containers and freight between Chinese ports and the nation's trading partners, but it also oversees a share of trade between third countries — such as shuttling goods back and forth between Spain and Brazil over the Atlantic Ocean. Alarm about this rising global dominance is shared on a bipartisan basis in Washington. "If China wanted to leverage their dominant role in global shipping to hurt our country, to hurt Americans, they could easily do that," Democratic Senator Mark Kelly of Arizona, who studied marine engineering in college before serving in the US Navy and later NASA, said at an event in September. Kelly co-sponsored a bill last year with Florida Republican Senators Marco Rubio and Rick Scott aimed at countering "the growing threat" of China in the world's oceans. Together with Rubio and Representatives Mike Waltz and John Garamendi, Kelly issued a plan for revitalizing the US maritime sector. Rubio is now secretary of state, while Waltz is Trump's national security adviser. Executive action has already been taken. Before leaving office, President Joe Biden blacklisted Cosco, along with China State Shipbuilding and China Shipbuilding Trading and others, over their alleged military links. Then under Trump, the US Trade Representative office proposed fees for the use of commercial ships made in China, along with other measures including a levy of as much as $1 million to be charged when Chinese-built vessels enter a US port. Trouble is, US merchant-marine capacity shrank dramatically during the period of efficiency-driven globalization. According to Waltz's estimates, the number of US shipyards by last year had dropped to 20 from 300 in the 1980s. The supply chains and workforces behind that infrastructure is also gone. At the same time, America remains a maritime nation — Gavekal Research estimates that 45% of US foreign trade by value, and some 79% by weight, is seaborne. The lead times for rebuilding such capacity are long. So for now, the US will likely have to lean hard on its allies that are still major shipbuilders: South Korea and Japan. "The paradox is that the main beneficiaries of its efforts will be Japanese and Korean companies," Tan Kai Xian, Gavekal's US analyst, wrote in a Feb. 24 note. Over the longer term, what remains unclear is how the US can support the shipbuilding, and other national security industries, without new spending. Stephen Miran, Trump's nominee to chair the White House Council of Economic Advisers, said this week that "we need to engage in defense-driven industrial policy, directing procurement and R&D budgets to activities useful for modern national security." But any effective effort to build out manufacturing capacity surely will require major fiscal outlays. As Congress turns to the annual appropriations process, with plans to add another $4 trillion-plus to the nation's $36 trillion national debt (in order to fund tax cuts), the question of reconstituting American maritime power is whether Washington will put its money where its mouth is. —Chris Anstey |

No comments:

Post a Comment