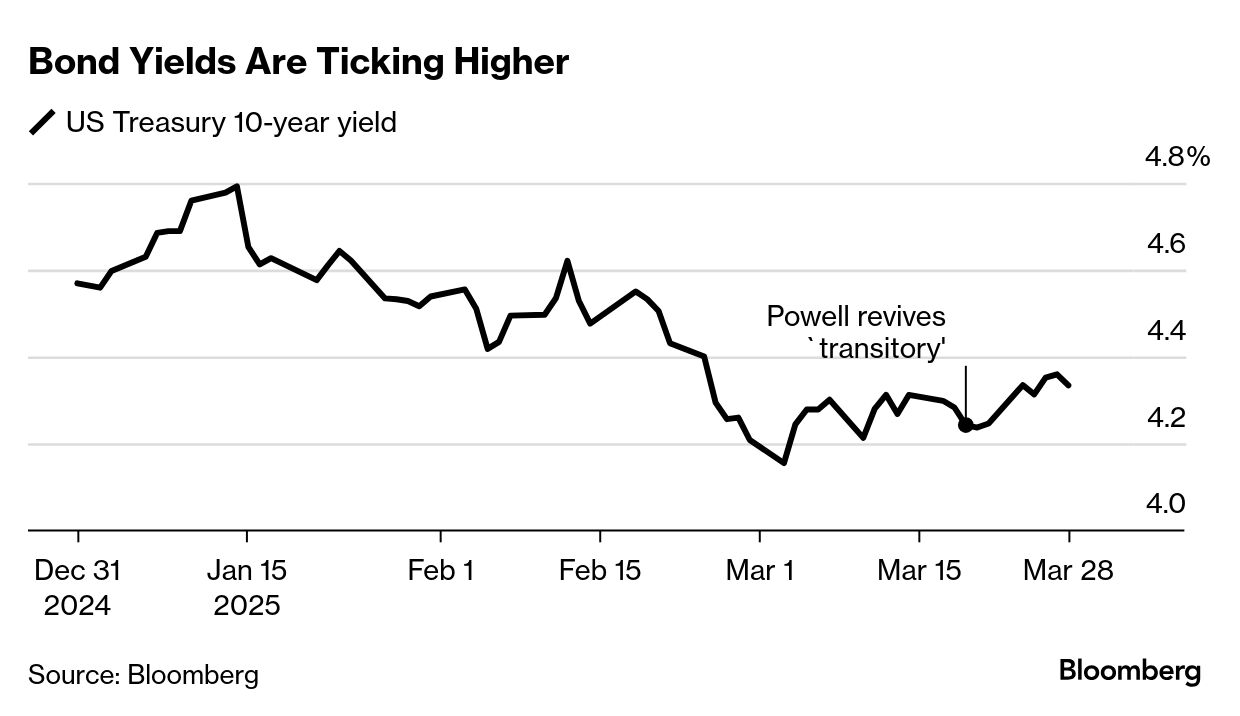

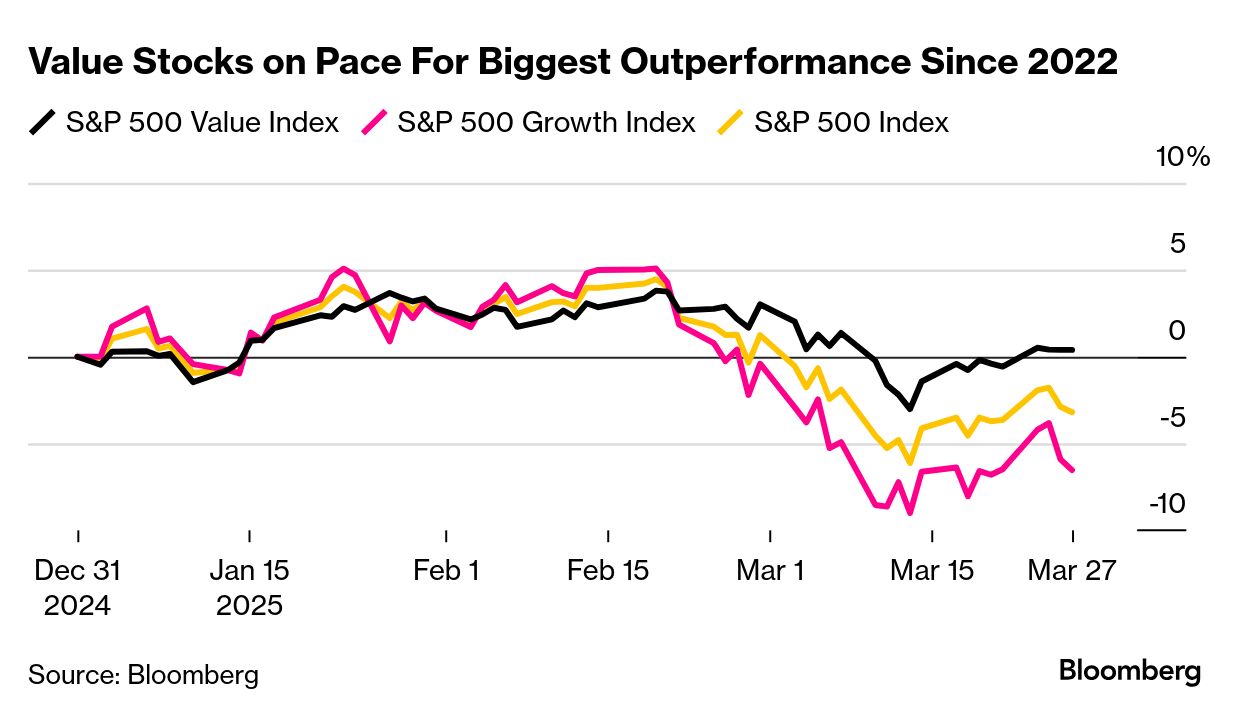

| Bond and stock markets rallied recently on hopes that the so-called Federal Reserve "put" was alive and well. Fueling the perception was Fed Chair Jerome Powell, who last week even resurrected the word "transitory" in reference to tariff-related inflation. He gave the sense to some investors that he'd be more responsive to slowing economic growth than any short-term price increases on the heels of levies from President Donald Trump. But any perceived clarity was muddied this week by the comments of individual Fed members, who sounded like they were on a different page from Powell. Take Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic, who was asked about his take on the "t" word on Monday with Bloomberg's Michael McKee. His response? "I'm not going to say that word. Nope." St. Louis Fed President Alberto Musalem was similarly skeptical, saying Wednesday that he'd be "wary of assuming that the impact of tariff increases on inflation will be entirely temporary." Federal Reserve Bank of Boston President Susan Collins said it looks "inevitable" that tariffs will boost inflation, and Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari also emphasized the pace of price growth, saying it's "above our 2% target so we have more work to do." The result in markets has been a battle between how quickly growth will slow and how sticky inflation will remain. A stagflation-like recipe has led to the continued breakdown of bonds' traditional role as a haven in times of turmoil. Even on down days for the S&P 500 and Nasdaq, US Treasuries of all maturities failed to rally in a meaningful way. This year's bottom for the 10-year Treasury yield was on March 3, when it reached 4.16%. Since then, 10-year rates have risen by 22 basis points, even as the S&P fell 2.5%. There's a larger point here in trying to understand the nuances of Fed speak. Central bankers don't have good tools to address weaker activity when consumer prices aren't retreating fast. The mantra "don't fight the Fed" arose in an era of low inflation and credit crises. This moment is different, with consumer prices increasing at a pace well above the 2% favored by central bankers for the past 48 months. If you believe that any rise in inflation is transitory, then the central bank can come to the rescue of the economy and, in turn, US bond markets and even equity valuations. But if you're still worried about a cycle of price hikes amid broader weakness, central banks are much less powerful. Torsten Slok of Apollo Management said in a report to clients this week that there is clearly a debate over the outlook within the Fed, calling the degree of disagreement "remarkable." He noted that according to the central bank's latest projections, one member of the policy-setting Open Market Committee sees the Fed's benchmark rate at almost 4% in 2026, while others think it will be just above 2.5%. One test for the Fed and therefore investors comes today and two more follow next week. Today sees the release of the personal consumption expenditures price index excluding food and energy — the Fed's preferred measure of underlying inflation. It probably advanced at an annual pace of 2.7% in February, according to the median forecast in a Bloomberg survey of economists. "Even if this report doesn't indicate any urgency for the Fed to cut rates, we think economic activity and the labor market will deteriorate in the second half of 2025. Ultimately, the Fed's wait-and-see stance in the first half of the year implies they'll have to lower rates by more later. We expect the Fed to cut by a total of 75 basis points this year." —Bloomberg Economics

Then next week, Trump is set to continue imposing tariffs on trade partners on April 2, although the degree he does so is still up in the air. That's followed a week from today by the US payrolls report for March. And finally, Powell speaks the same day on the economic outlook. —Lisa Abramowicz |

No comments:

Post a Comment