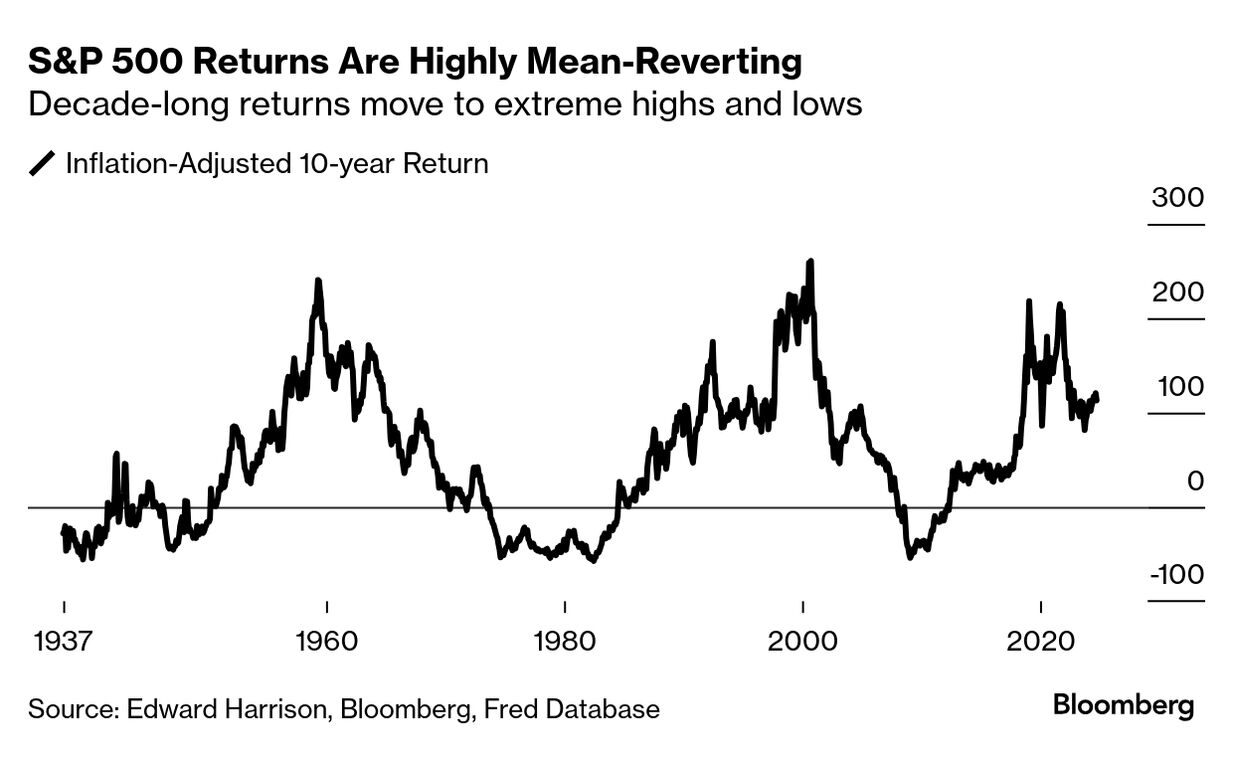

| If you look at the Japanese super bubble and those previous two in the US, in each case the bubble popped after monetary policy tightened. In Japan, loose monetary policy after the 1985 Plaza Accord finally came to an end in late 1989, leading to a spectacular fall of two-thirds in the stock market by mid-1992. In the US, the Greenspan Fed started hiking rates in June 1999, with the bubble popping the next year. And in 1959, the Fed raised the discount rate from 2.5% to 4%, precipitating a recession that began a decades-long dive in long-term market returns. Here's the thing, though. There was no crash in the stock market in 1959. Stocks gained 8.5%, and the next year the S&P 500 lost 3% but then gained 23% in 1961. So in a very real sense, while tighter policy precipitated the long-term decline, it didn't pick up in earnest until inflation came rip roaring in the latter half of the decade during the "Guns and Butter" strategy of Lyndon Johnson. Inflation never fully receded from view after that until Paul Volcker crushed the US economy with spectacularly high interest rates more than a decade later. In some senses, then, what we are experiencing now is a lot more akin to 1959 than to any of the other supper bubbles I've mentioned. And just like back then, we may not see a real deflation in equity prices unless inflation becomes entrenched and pronounced or the guns-and-butter strategy that has the US federal government deficit at 6% of GDP goes away. That— and the fact that the peak returns during the latest super bubble were lower than during the previous two — allows for some hope that the bubble just deflates instead of popping. Trump could bring about a crash | There are two ways that Trump can bring about a crash — and unfortunately he's doing or promising to do both right now. First, there's inflation. As Grantham put it in his talk with Merryn Somerset Webb: Ben Inker at GMO and I, 25 years ago did a behavioral model which says forget all the logic about the efficient market or how it should work and dividend discount models and all that, just let's see what actually it explains and what is explained since 1925 and explained very well indeed is low inflation, the market loves it. High inflation, it hates.

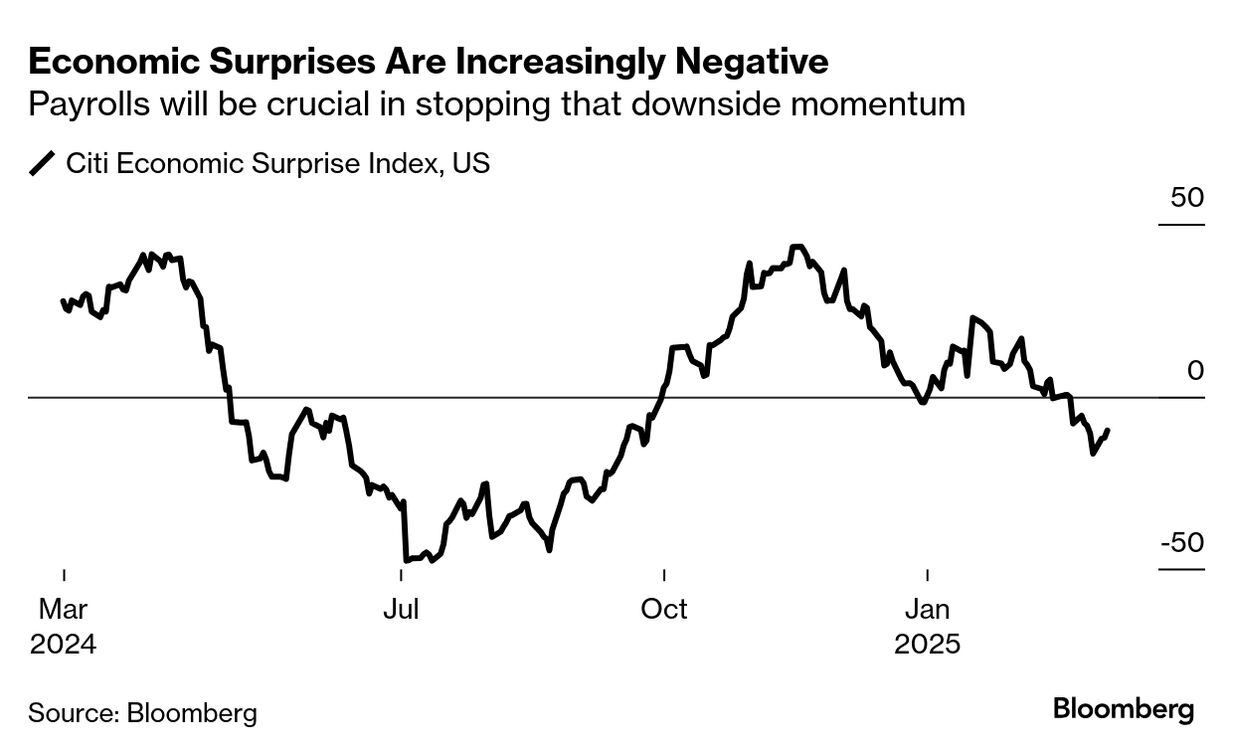

Exactly right. The 1959 climb-down only picked up steam after 1967, when the inflation rate went from 3% to 5% by 1971, precipitating another monetary policy tightening and recession. If Trump's tariffs are more than a one-time price step-up, something that inflicts lasting damage on inflation rates due to unanchored inflation expectations, we could go from 3% CPI to 5%, just like in the late 1960s. And the exact same scenario would play out, with the Fed being forced to hike rates and the economy falling into a recession, spurring deep losses for stocks. Trump could also take DOGE a step further. As my Bloomberg colleague Claudia Sahm put it on her Substack newsletter recently, "Civilian federal employment (including the Post Office) is currently 3 million, or less than 2% of the labor force." DOGE may be divisive. But cuts by DOGE simply aren't large enough in and of themselves to cause a recession. If Trump takes a sledgehammer to defense spending and Medicaid, or touches Medicare or Social Security, we'd be looking at a much more impactful restriction in fiscal largesse. I would go as far as saying that just reaching the 3% deficit goal of Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent from today's 6% level would be enough to cause a recession. But nothing I have seen so far — either from DOGE or tariffs — is in that order of magnitude. Still, some of the economic numbers of late have been truly awful. The US economy is just barely growing right now. And if you believe the latest GDPNow tracker from the Atlanta Fed, the economy could even be contracting. It won't take much to tip the US into recession. Most recessions begin with a cutback in capital investment. And so, to the degree tariffs stop firms from making investment plans, they could have a very negative impact catalyzing a downturn. What's more, extreme valuations make the market extremely vulnerable. I'm not talking about Nvidia or Tesla. Those are known extremes. I am talking about companies like Walmart, Coca-Cola and Proctor & Gamble that you might expect to benefit from the recent rotation into defensive stocks. Walmart trades at 38 times earnings, with an astronomical price to growth ratio of 4.4. That says the valuation multiple is four times the rate of actual earnings growth. Coca-Cola might have a more reasonable P/E ratio of 24. But you're still paying 4.2 times as much as the underlying growth rate. And the metrics for Proctor and Gamble are about the same as they are for Coca-Cola, by the way. This market is overvalued from top to bottom by almost all standard valuation metrics. And it's not just growth stocks, which are expensive. Almost every stock is expensive. This is why Warren Buffett isn't buying stocks, including his own, and why he is sitting on a record amount of cash. What's the takeaway? The data haven't deteriorated enough to think we are at the tipping point for an epic bear market, as I argued last week. But this isn't a time to load up on risk. The downside risks in the market are rising and the valuation makes it vulnerable to any further rise in inflation or cut in the federal deficit. Either of those two outcomes will precipitate the next bear market. P.S. — On that Grantham podcast episode: You can find it on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts. And a thought: I know Grantham has been written off by some of you as a perma-bear. I don't see it that way. He's a value investor who has suffered during an investment climate that has been extremely hostile to value. We see that in Buffet's record cash pile. I highly recommend this particular podcast. Listen to it with an open mind in the context of everything that's happening right now. You wont regret it. |

No comments:

Post a Comment