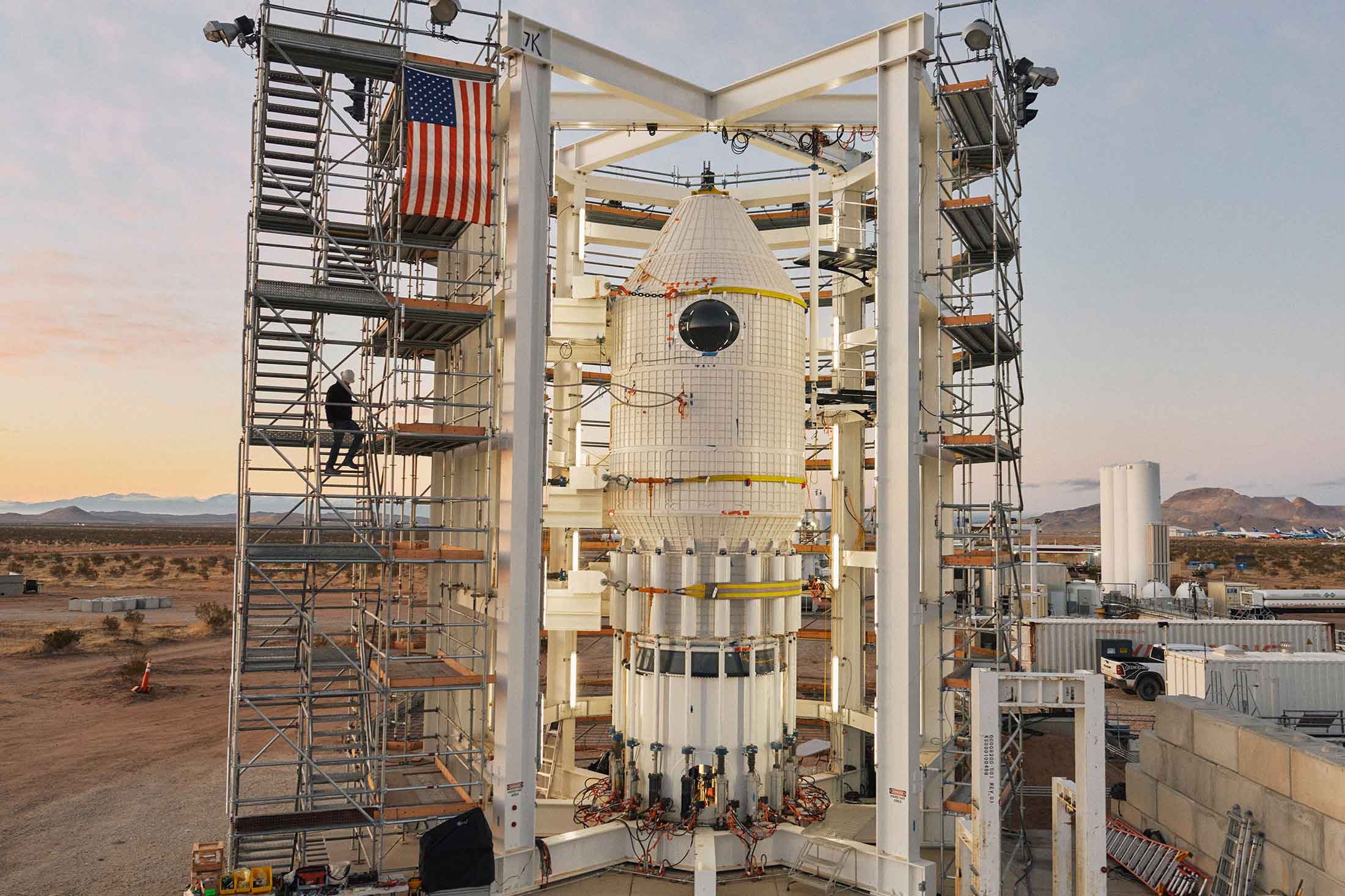

| For a November 2023 issue of Bloomberg Businessweek, Olivia Carville and Margi Murphy wrote about a group of young women in a New York City suburb whose photographs had been manipulated into pornography. Margi writes for the newsletter today about Levittown, a six-part podcast in which they dive deeper into the topic. Plus: A crypto billionaire pursues his dream of building a space station. If this email was forwarded to you, click here to sign up. The internet age has ushered in a new category of personal victory: the feeling of identifying a harasser, blackmailer or vicious troll. That satisfaction is sweeter still if you're a cop or a prosecutor and can charge them with a crime. Or if you witness the overwhelming relief of a victim tortured by not knowing who'd been hiding behind the screen. In a new podcast, my colleague Olivia Carville and I set out to understand exactly who was behind a global clearinghouse of nonconsensual deepfake pornography affecting countless girls and women around the world. Our reporting begins at a school in Levittown, New York. Long known as America's first suburb, Levittown in 2023 gained notoriety when reports emerged that dozens of women had found out that someone had transformed innocent photos of themselves—with the help of artificial intelligence, and without their consent—into pornography. The case led to the first deepfake-porn-related conviction and had profound effect on one resident, Kayla, as it rippled through her close-knit community. Combining their own sleuthing with the work of law enforcement to dig up a law on the books to charge the perpetrator, Kayla and the women of Levittown eventually found some solace.  General Douglas MacArthur High School in Levittown in 2023. Photographer: Shravya Kag for Bloomberg Businessweek Since then, stories like the ones we found in Levittown have become far more widespread. With federal law remaining largely silent on the legality of creating nonconsensual deepfake pornographic images, state prosecutors have scrambled to find charges that fit a new kind of harassment. AI-based deepfaking services are hitting a peak. Traffic to the 10 most popular "nudifying" apps soared by more than 600% year over year, from 3 million views in April 2023 to 23 million in April 2024, according to figures provided to Bloomberg by a research company that asked not to be identified in connection with its data on online pornography. In January this year alone, the websites received 18 million views, the research shows. With a stamp of approval from first lady Melania Trump, lawmakers this year are expected to pass a bill criminalizing the posting of nonconsensual pornographic deepfakes on the internet. It will penalize the posters with prison time and the platforms with fines if they don't remove the fake pictures quickly enough. The proposed Take It Down Act, which passed in the Senate in the last Congress with bipartisan support, wouldn't outlaw the apps themselves. So San Francisco City Attorney David Chiu last year tried to tackle the root cause. He brought a first-of-its-kind lawsuit charging the deepfake app creators, arguing they broke federal and state revenge and child pornography rules and broke California's competition law. The apps named in the lawsuit have either closed or appear to be operating under different names. Some have geofenced their services so they can't be accessed in the state. Out of 16 apps named, representatives of only one of them have responded to Chiu's complaint. It turns out finding a real person to serve papers to, or in our case—ask questions of—is an almost impossible task. The irony that the owners of these services are often able to operate anonymously while they make money from exposing others wasn't lost on Olivia and me. As we tried to track down the people behind the latest, fastest deepfaking apps, we learned that the competitors in this rapidly growing industry had more in common than meets the eye. The Take It Down Act doesn't take aim at the deepfake providers (perhaps to avoid questions of censorship, which must be taken into account, too). But teachers, schools and parents told us that—clear harms to the victims aside—the ease with which children can access these apps allows them to create sexually abusive material without fully grasping the consequences. They questioned whether there needs to be more accountability on the app maker's side, too—to make it harder for these services to end up on young people's phones. Our first episode of Levittown is out today, with more coming this weekend. I hope you check it out to understand how the side effects of some of the most cutting-edge technologies are having a huge impact on young people—and join us on a wild journey around the shadowy corners of the internet. |

No comments:

Post a Comment