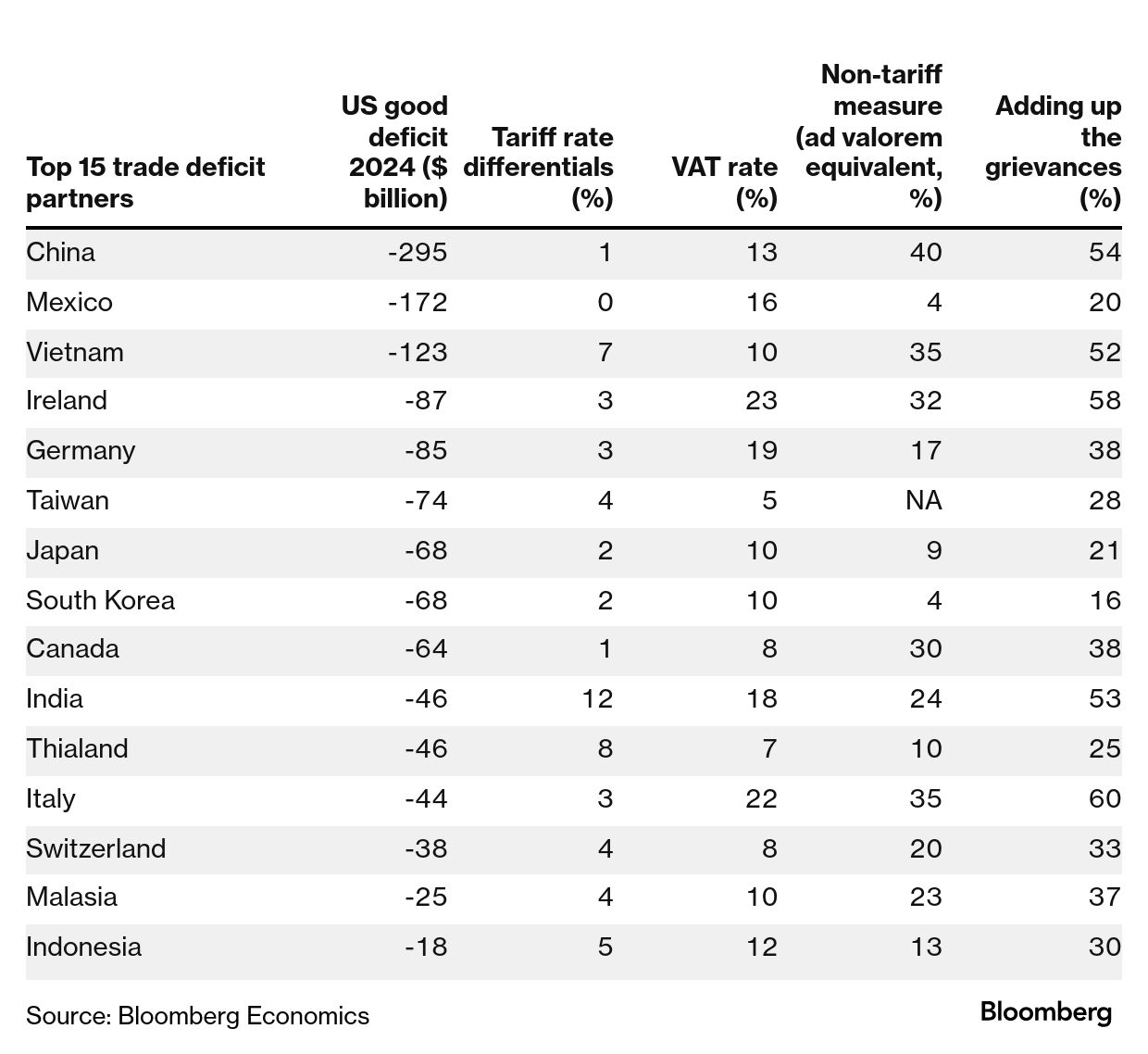

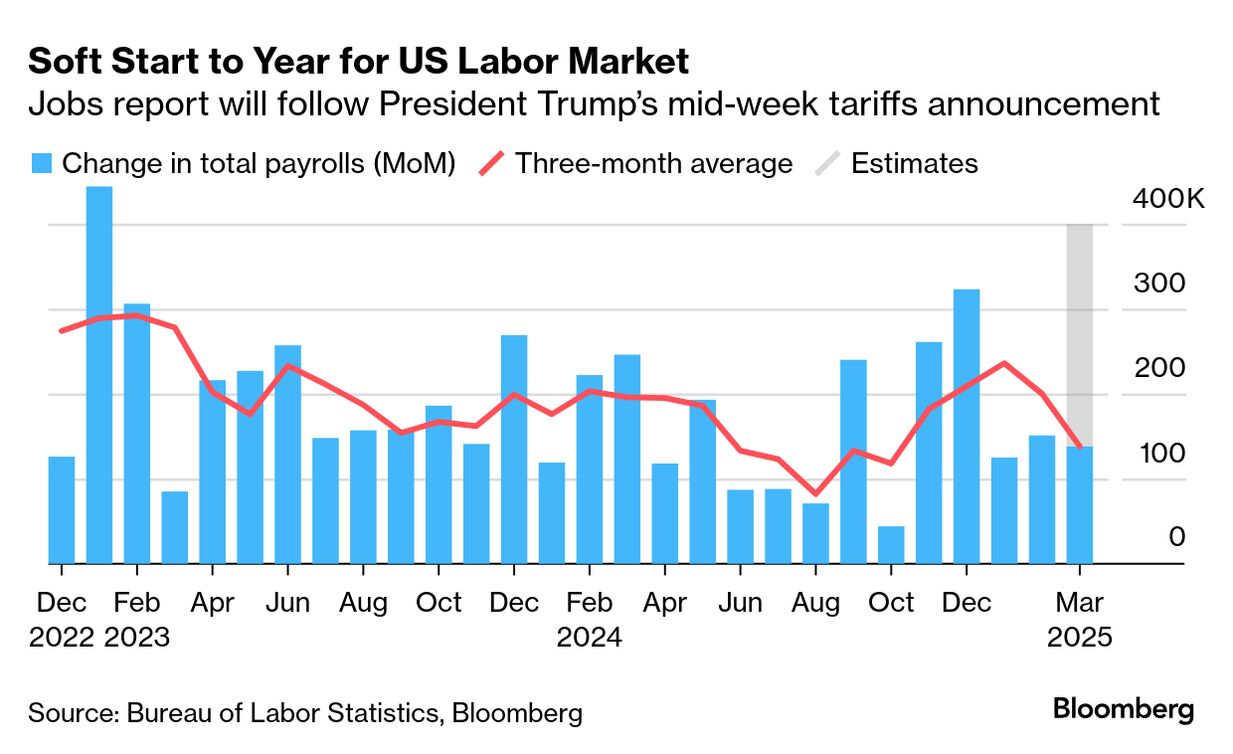

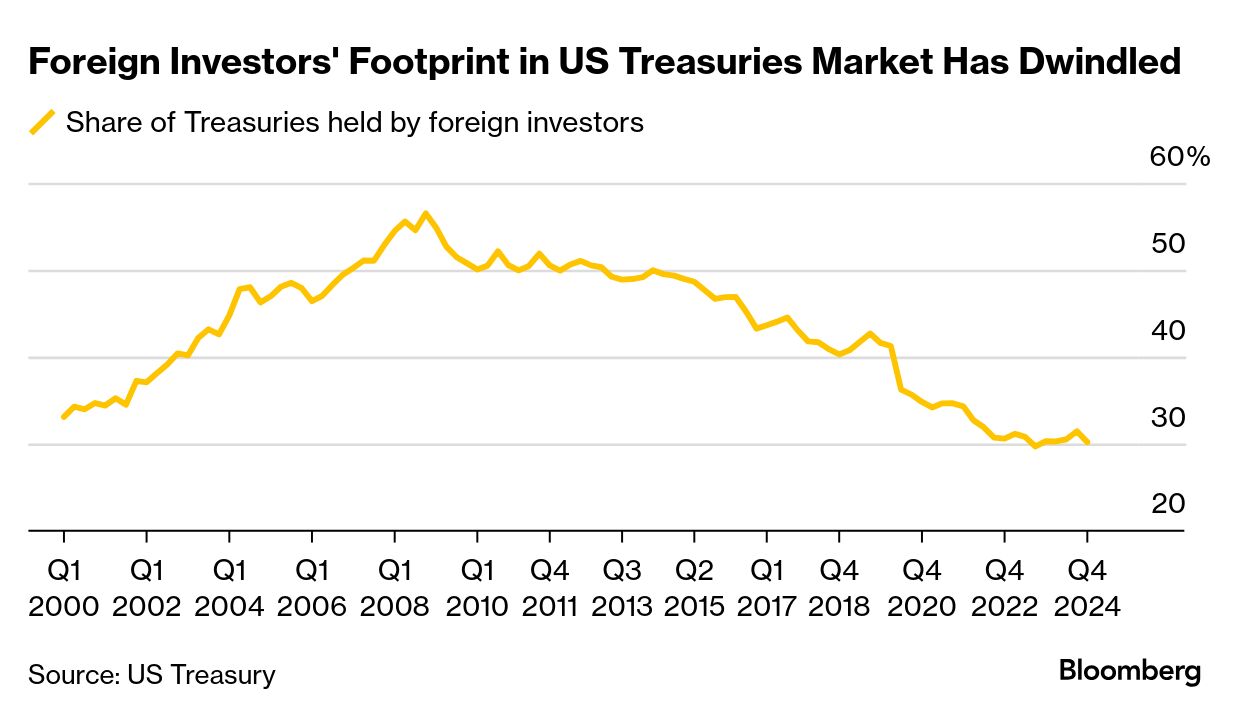

| I'm Katia Dmitrieva, Asia economics reporter in Hong Kong. Today we're looking at reciprocal tariffs hitting Asia. Send us feedback and tips to ecodaily@bloomberg.net or get in touch on X via @economics. And if you aren't yet signed up to receive this newsletter, you can do so here. Back in the 1960s, South Korean officials began a targeted policy of industrialization that within one generation, took the Asian economy from a developing one reliant on agriculture to a developed giant that ranks among the world's largest. Key to this transformation — dubbed a miracle by economists in the years following — was trade. The government invested heavily in a rapid industrialization that pivoted growth towards manufacturing and chemical exports. Officials incentivized global commerce while keeping import tariffs broadly low, aside from strategic industries that the country relied on for growth such as autos. It was a process that Japan had undergone following the Second World War, and that nations across Southeast Asia, from Vietnam to Indonesia, hoped to replicate as their own manufacturing sectors kicked into high gear in the 1980s. The problem is that this model doesn't work well with high US tariffs. Countries across Asia's $41 trillion economy are about to face this troubling reality, as Trump readies what he calls reciprocal levies, as we report here. How do we know that Asian economies are set to be in the crosshairs of these amorphous tariffs? Trump has already called out several countries by name, including South Korea and Japan. His administration has already slapped 20% levies on China. And Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent said the target is the "dirty 15." It turns out that 15 nations make up about three-quarters of US trade deficit, with nine in Asia, according to Bloomberg Economics. It will prove a generational test for Asia's economies that forces leaders to make some tough decisions. So far, that's meant a lot of negotiating and promises to purchase US goods. It's not in nations' best interest to retaliate in-kind, as Wendy Cutler, formerly a longtime USTR official, tells us: "Asian countries are loathe to retaliate," especially after Canada provided a cautionary tale for what happens when you fight fire with fire from the world's largest economy. One route for countries here — which, by the way, includes places like Vietnam that gained from increased investment from the US following the first trade war that began in 2018 — is to boost intraregional trade. In other words, rely on China and each other to keep fueling growth. Though with China's economic tumbles and long road to boosting consumption sustainably, even that path may be in trouble. The Best of Bloomberg Economics | US employers probably tempered their hiring in March, just as consumers grow increasingly cautious and the economic outlook dims on concerns about the fallout from higher tariffs. Payrolls rose by 138,000, below the 151,000 increase a month earlier, according to the median projection of economists surveyed by Bloomberg. That would leave average job growth over the past three months at the slowest pace since October. The unemployment rate is seen holding at 4.1%. Shortly after Friday's jobs data, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell will discuss the economic outlook. Anxiety is building among households and businesses about Trump's aggressive trade posture. The US president on Wednesday is expected to unleash his biggest tariff salvo to date — a package of blanket increases in duties on foreign imports. Elsewhere, policymakers around the world will be watching for the April 2 tariff announcements. Central-bank decisions from Australia to Colombia may result in unchanged rates, while crucial inflation data in the euro zone will be a highlight. See here for the rest of the week's economic events. A basic premise for the idea of a so-called Mar-a-Lago accord between the US and other major economic powers, put forward in November by Stephen Miran before he became White House chief economist, is flawed, according to Deutsche Bank analysis. Miran has argued that, because the dollar is the key reserve currency, other nations must then accumulate it, causing an overvaluation that then hollows out US industry. But data show "reserve accumulation actually correlates inversely with dollar strength — foreign central banks tend to divest dollar holdings during appreciation periods,'' a Deutsche Bank team including Peter Sidorov wrote last week. And they've tended to stock up when it's weaker. More broadly, foreign nations' share of Treasuries has dwindled over the years, and most developed countries "no longer hold large reserves," making a 1985 Plaza Accord-type deal "untenable," the team said. If Washington wants the dollar weaker while retaining its global-reserve role, the way to go would be to shrink the fiscal deficit, they said. That would lower US interest rates and the dollar, while bolstering its reserve attractiveness, the team said. |

No comments:

Post a Comment