| The auditions to be the next CEO of Disney are in full swing. On March 4, Entertainment co-Chair Dana Walden appeared at a Morgan Stanley conference to tout the profitability of Disney's streaming services. Days later, parks chief Josh D'Amaro and Walden's co-Chair Alan Bergman appeared at South by Southwest to discuss their creative collaborations. These public appearances aren't designed as tests. CEO Bob Iger is asking his top deputies to represent the company on his behalf and giving them a chance to own their victories after a good run. Yet they do provide the board and investors with moments to assess the internal contenders. Walden's appearance at an investor conference addressed her perceived weakness — the Wall Street side of being a CEO — while D'Amaro's appearance at a creative event addressed his — that he's a parks guy with little experience in film or TV. D'Amaro also touted his growing interest in video games — a potential growth area for Disney — when he went for a walk around Disneyland with my colleague Thomas Buckley. (I spoke with Walden about her growing portfolio late last year.) Anyone who says they know who will be the next CEO of Disney is lying — unless their name is James Gorman. But D'Amaro and Walden remain the two most likely candidates. Disney declined to comment. The board is still leaning toward an internal choice, according to people familiar with the matter, and it has identified four insiders: Bergman, D'Amaro, Walden and ESPN Chairman Jimmy Pitaro. They all possess different backgrounds that give the board a range of options without looking outside. It's hard for any outsider to understand Disney's distinct culture and its hold on consumers. And there isn't much time for an outsider to learn if Iger is really leaving at the end of next year. Pitaro has communicated to both friends and the board that he's not interested in the role. Bergman, though Walden's equal in the organizational structure, has never been seen as an equal rival for the top job. That brings us back to D'Amaro and Walden. That doesn't mean the job is certain to go to an internal candidate. When Disney said that it would announce a new CEO in early 2026, most people in Hollywood took that to mean the company was using the time to consider outsiders. The internal candidates have all worked at Disney for a few years, if not longer. So why would the board need another 18 months to make a decision? Headhunters are vetting external candidates and the press has floated names such as Electronic Arts CEO Andrew Wilson and Mattel CEO Ynon Kreiz. The board hasn't formally interviewed either for the role, said the people, who asked not to be identified discussing internal deliberations. Kreiz worked at Disney once before, after selling Maker Studios to the company in a deal that didn't end well. (Wilson and Kreiz declined to comment.) The list of outside candidates with obvious experience is short. Former deputies Tom Staggs and Kevin Mayer aren't in the running this time. Iger has always liked Warner Music CEO Robert Kyncl, who happens to be close friends with Kreiz, but he's got his hands full at Warner. Would leaders from Netflix or YouTube — Disney's two biggest rivals in video — have any interest? Delaying the decision until early 2026 has a practical effect. It has muted speculation about a topic that was becoming a distraction both internally and externally. Executives had been interpreting every decision by Walden or D'Amaro as part of a play to look good in front of Iger. It also allows the board to fully own the decision. Iger has received a lot of criticism for his handling of succession. He said he would leave and then extended his term. He anointed Tom Staggs as his successor and then changed his mind. When Iger finally did give up the CEO job, he clashed with his successor, Bob Chapek, and ultimately returned to replace him. Failed succession is the biggest stain on the legacy of an executive long seen as the best CEO in his field. Iger is clearly intent on fixing that (and stabilizing Disney before he leaves). That involves receding from public view. While Iger made a number of public appearances in his first year back on the job, he has done little more than the obligatory quarterly earnings calls over the last 15 months. And though Iger will mentor and train his potential successors, he has told confidants that he's less involved in the actual vetting and selection this time around. While it's hard to imagine the board ignoring Iger's opinions, Gorman, the former CEO of Morgan Stanley, is firmly in charge of the process. He leads the board's succession planning committee, which also includes General Motors CEO Mary Barra and Calvin McDonald, CEO of Lululemon. The committee met seven times in fiscal 2024. Which means the real pressure right now isn't on the candidates. It's on the board. Disney has flubbed this process so many times and faces significant challenges. It plans to introduce a new sports streaming service later this year, is trying to get consumers to spend more time with Disney+ and faces growing competition in theme parks. The next leader will determine the company's future across a broad swath of businesses. The sooner the board makes up its mind, the better for everyone involved. But they have to get it right this time. The Best of Screentime (and other stuff) | Spotify really, really wants artists to stop criticizing it | About 1,500 acts make at least $1 million from Spotify every year. Some 10,000 musicians make at least $130,000. That's according to a report from Spotify, which is eager for musicians and the press to celebrate its contributions to the music business. It's easy to understand why co-founder and CEO Daniel Ek wants to feel the love. Recorded music sales have grown for a decade; thousands of artists make a living from streaming alone (to say nothing of touring). And yet, the music business has been reluctant to applaud Spotify. Artists bemoan how little they get paid per stream. Songwriters say they are getting shafted. Spotify's numbers are a little misleading, as noted by Jem Aswad. Just because Spotify pays out $5 million for an artist's work, it doesn't mean the artist gets that money. Record labels, publishers and performing rights organizations all take cuts. But that's more of an issue between artists and their business partners — not Spotify. Another sign of a music slowdownRecorded music sales grew 6.5% last year, a slower pace than the year before. This is why so many music companies are pushing for more expensive tiers and alternate ways of making money from artists. A few other notes from these music reports: - Independent labels are increasing their share of sales at the expense of the majors.

- Artists who release music on their own through platforms like TuneCore and DistroKid are suffering a bit after streaming services limited which artists could make money.

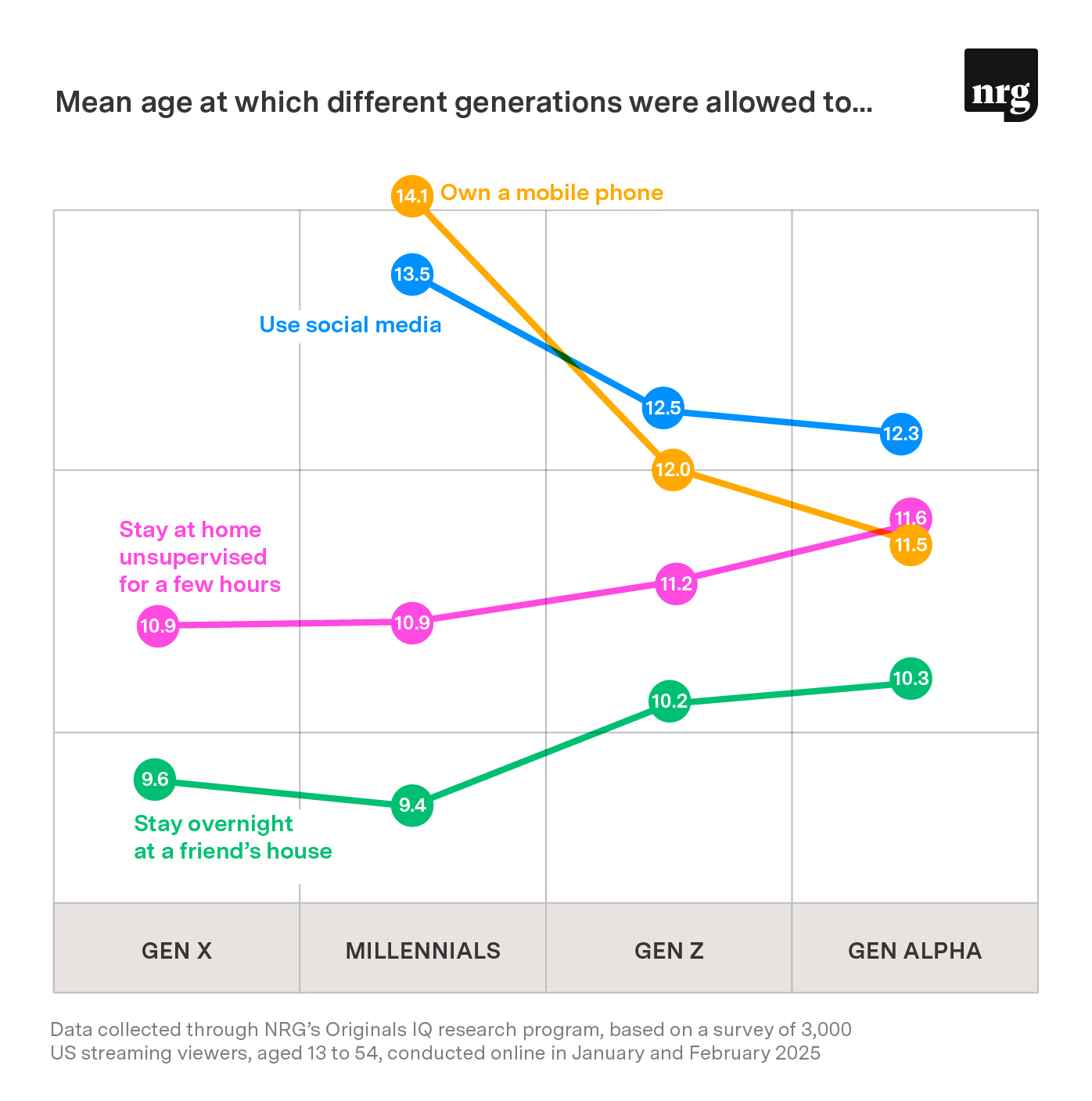

- Among the majors, Sony Music was the winner last year, while Universal Music and Warner Music lost share. Universal is still No. 1 overall.

The No. 1 movie in the world is…The Electric State. Despite poor reviews, it's the top movie on Netflix in dozens of markets. Last week I wrote as though Netflix had already released The Electric State. My mistake. Though it did play in a few movie theaters, it didn't drop on Netflix until March 14. No movie grossed $10 million at the US box office this weekend. It's been the worst weekend of the year. Yikes. One bright spot? The latest Bridget Jones movie … it's only on Peacock in US, but took in $100 million abroad. Bridget Jones movies have always been much bigger outside US. The last one made just $24 million in the US but $211 million globally. News flash: the music industry is super white and maleAbout 87% of senior executives at 37 of the biggest music companies are men. More than 92% of them are white. That's according to a study from the University of Southern California, which reported that the numbers have reversed since it started researching the subject. We shall see if these reports continue in the current anti-DEI moment. Almost 20% of teens use a phone in movie theatersIf you want to know why Hollywood executives are worried about YouTube and Instagram, consider this data from the National Research Group. More than 60% of teens use their phones while watching TV and movies at home. Almost 20% of teens use their phones while in a movie theater. Parents are all but encouraging this behavior. For the first time, the average kid is getting a phone before being allowed to be home alone. What are kids doing on their phones? If not texting, probably watching YouTube. Deals, deals, dealsThere is a new album from Youth Lagoon, a project from Trevor Powers. I was very into Youth Lagoon a little more than a decade ago and I am happy to report that this album has lured me back. I have been catching up with Hirokazu Koreeda's TV show Asura while in Tokyo. You should check it out on Netflix. Finally, two interesting articles from the weekend Financial Times: one about a Saudi TV show that has been banned in Iran and Iraq and another about concern that the UK isn't breaking many new music artists. |

No comments:

Post a Comment