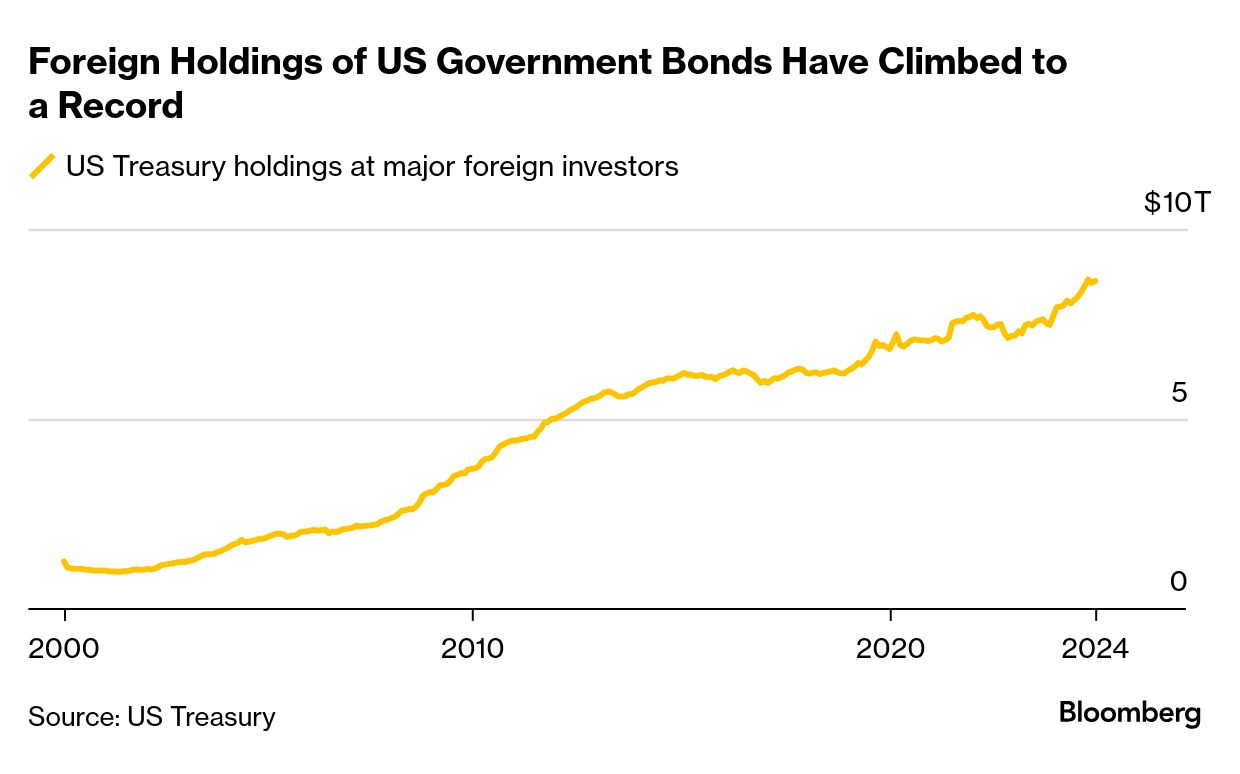

| US President Donald Trump's return to power has fired up dollar bulls—and for good reason. The greenback surges against the likes of the Mexican peso and Canadian dollar whenever he or his lieutenants proclaim tariff hikes are in the offing (perhaps as soon as today). But all of those threats are worsening a fundamental dilemma in the currency market, one recently highlighted by one of Trump's potential incoming advisers. Stephen Miran, Trump's nominee to lead the White House Council of Economic Advisers, advocated a wholesale "restructuring of the global trading system" in a paper published in November, then in his role as a strategist at hedge fund Hudson Bay Capital. He pointed to a problem: the dollar is persistently overvalued thanks to its status as the world's reserve currency. A too-strong exchange rate erodes export competitiveness, handicapping American manufacturing and potentially becoming a security issue by undermining the nation's ability to produce arms that keep it a top military superpower. The danger is that, at some juncture, a tipping point is reached when the reserve currency nation's economy has been so hollowed out that global investors no longer want its assets. That would usher in a "wave of global instability," according to a theory cited by Miran. While the US is still far from any such threshold, he lists a portfolio of measures the country could take to address the accumulating imbalances. They go beyond just tariff salvoes, which—as his paper anticipated—are already emerging as the first option.  A dealer eats lunch as he monitors a screen in the trading room at foreign exchange brokerage Gaitame.Com Co. in Tokyo in October. Photographer: Kiyoshi Ota/Bloomberg This week in the New Economy | Miran, whose appointment needs Senate confirmation, draws on the work of Belgian economist Robert Triffin, who came up with the theory that the world's reserve currency can become persistently overvalued due to its very status—dubbed the "Triffin dilemma." The theory explains that the demand for reserve assets around the world means the main nation must run persistent current-account deficits in response. In practical terms, that refers to how, as foreign capital pours in, dollars are going out, spent on imported goods. And indeed, foreign holdings of US Treasuries are quite large: some $8.6 trillion by latest count. An even broader measure is the US net investment position. Stephen Jen at Eurizon SLJ Capital said foreigners own $25 trillion more in American assets than Americans have in overseas holdings. That's about 85% of US GDP, up sharply from 20% in 2012. As that overseas cash arrives in the US, dollars keep heading abroad via trade deficits—in December, the US excess of imported goods over exported ones reached an unprecedented $122 billion. "From a trade perspective, the dollar is persistently overvalued, in large part because dollar assets function as the world's reserve currency," Miran wrote. "This overvaluation has weighed heavily on the American manufacturing sector while benefiting financialized sectors of the economy." Once the US becomes unwilling to bear these consequences, it'll take steps to upend the status quo—such as tariff hikes. Other measures draw from financial markets. Trump's aides could have him use the International Emergency Economic Powers Act—which has already been floated for tariffs—to disincentivize the accumulation of Treasuries by way of applying a user fee. The US could move to weaken the dollar's exchange rate by accumulating foreign currencies. The Trump administration could also seek a Plaza Accord-like deal with key foreign trading partners to soften the dollar, something Jen also has highlighted. "Import tariffs would make imports more expensive and incentivize domestic production but would not promote US exports. A dollar devaluation would achieve both," Jen wrote in a recent note to clients. In 1985, the US, Germany, Japan, France and the UK agreed to joint action that would bring down an overvalued dollar. Jen suggested any similar agreement under Trump could be done on the 40th anniversary of that deal, in September, named after the New York City hotel where it was struck. He's not the only one with the idea: Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent said last year, before Trump nominated him, that a new deal would be named the "Mar a Lago accord," after Trump's Florida property.  Scott Bessent Photographer: Al Drago/Bloomberg Still, getting the likes of China and Japan along with Europe on the same page appears challenging at this stage. Miran wrote that tariff action is likely to precede the use of any currency tools. That means the dollar is likely to strengthen further before it reverses, he wrote. "There is a path by which the Trump administration can reconfigure the global trading and financial systems to America's benefit, but it is narrow, and will require careful planning, precise execution, and attention to steps to minimize adverse consequences," Miran wrote. —Malcolm Scott |

No comments:

Post a Comment