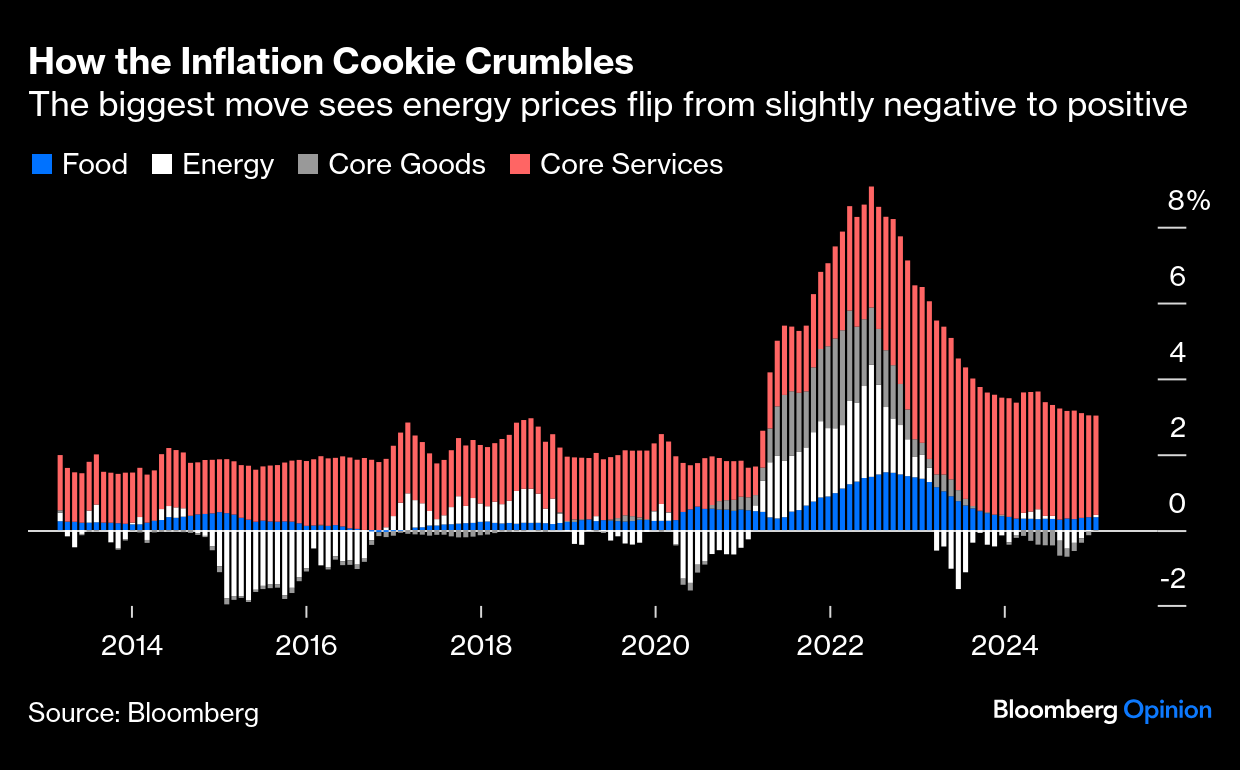

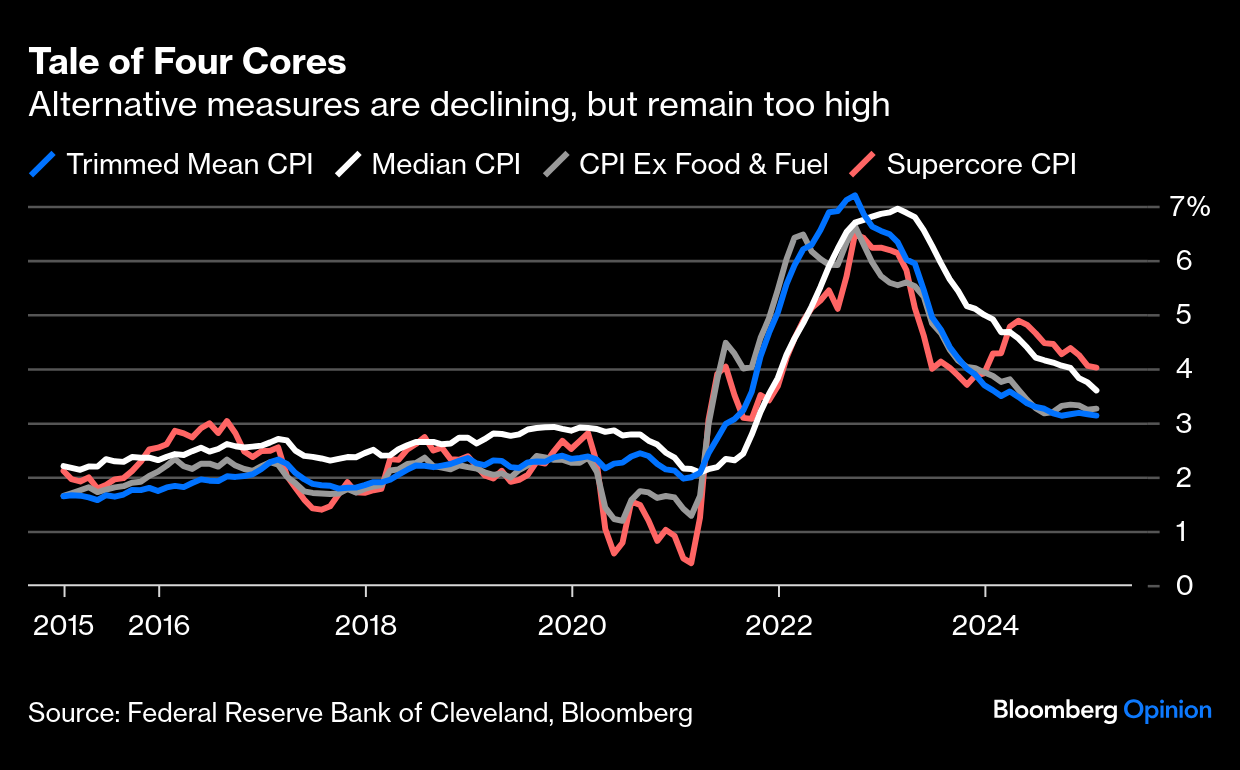

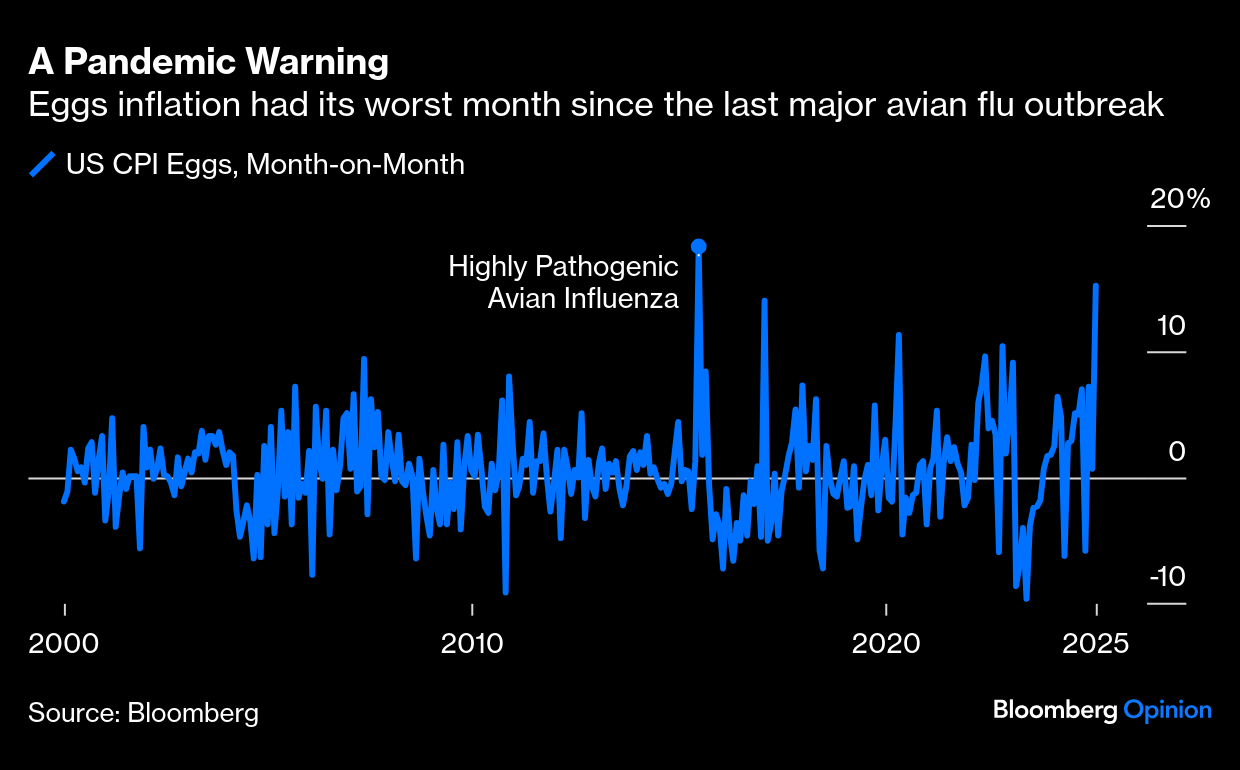

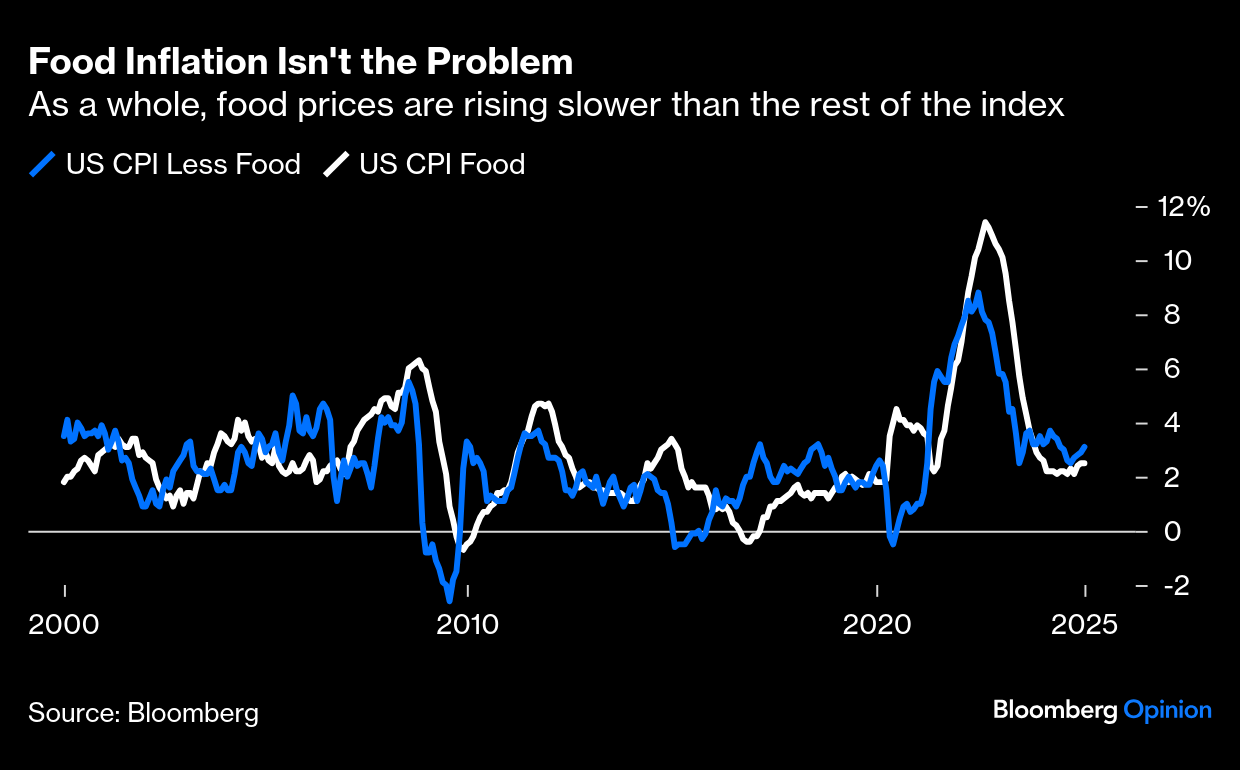

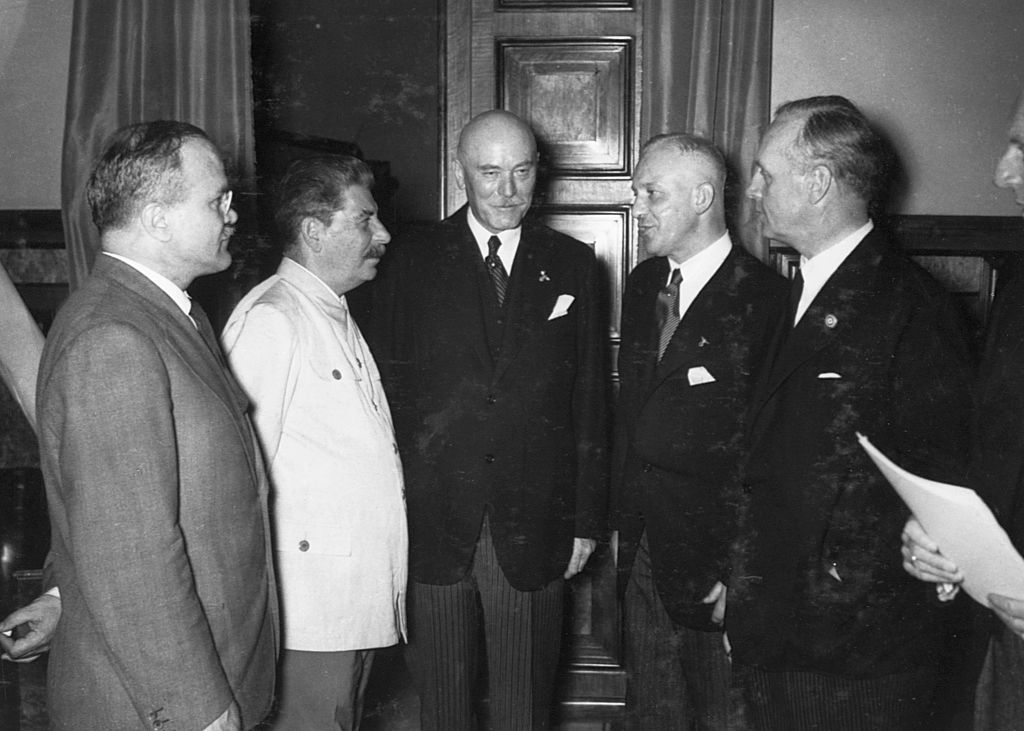

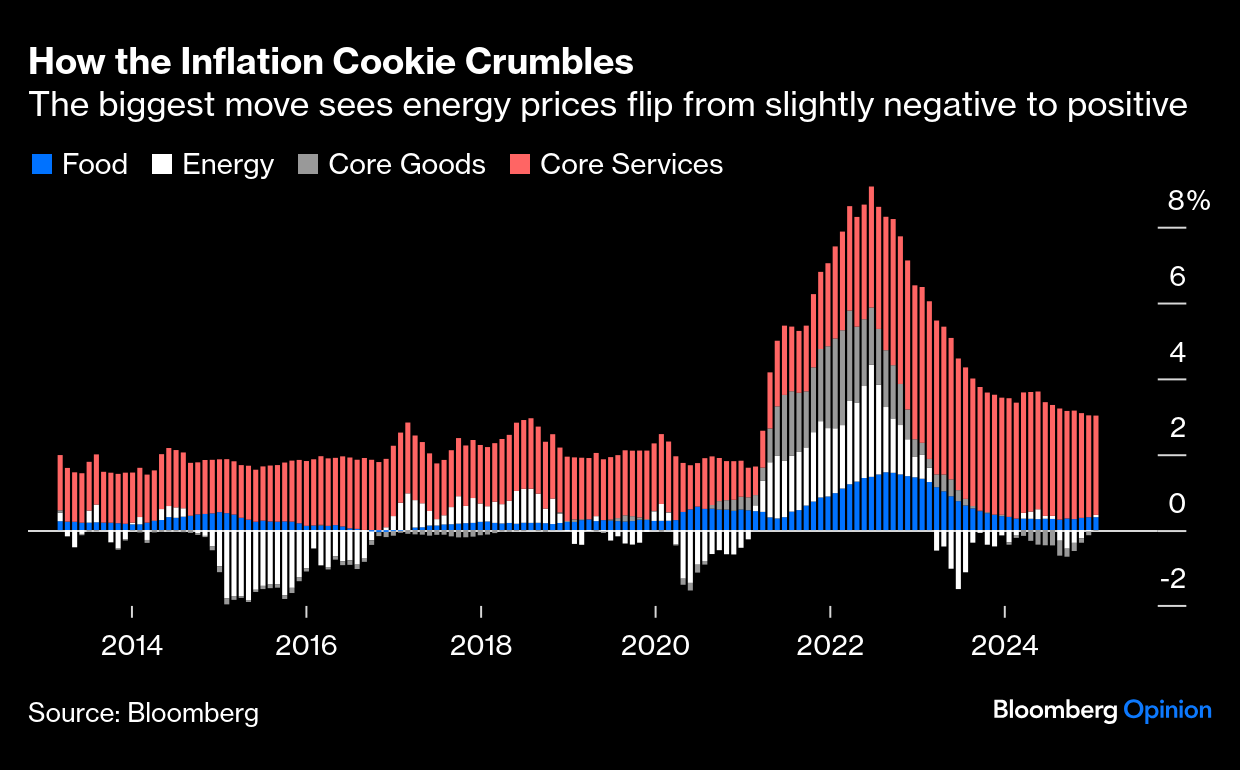

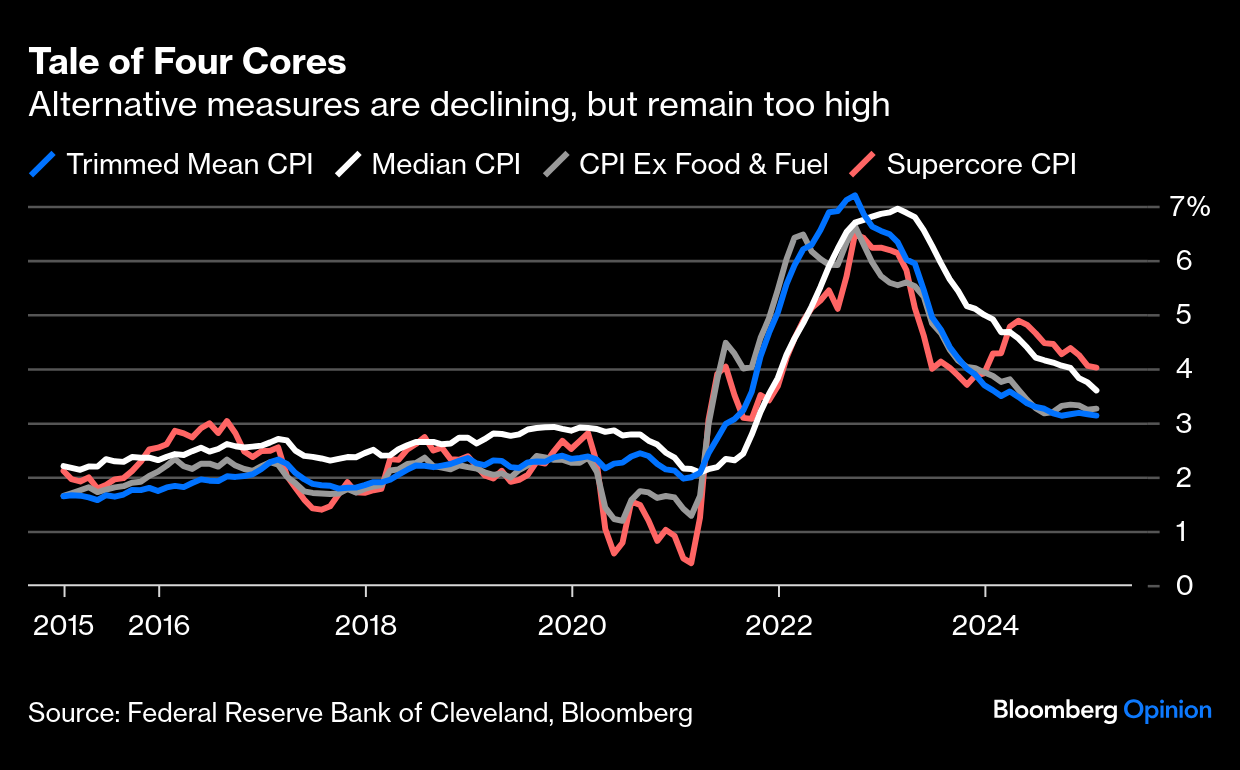

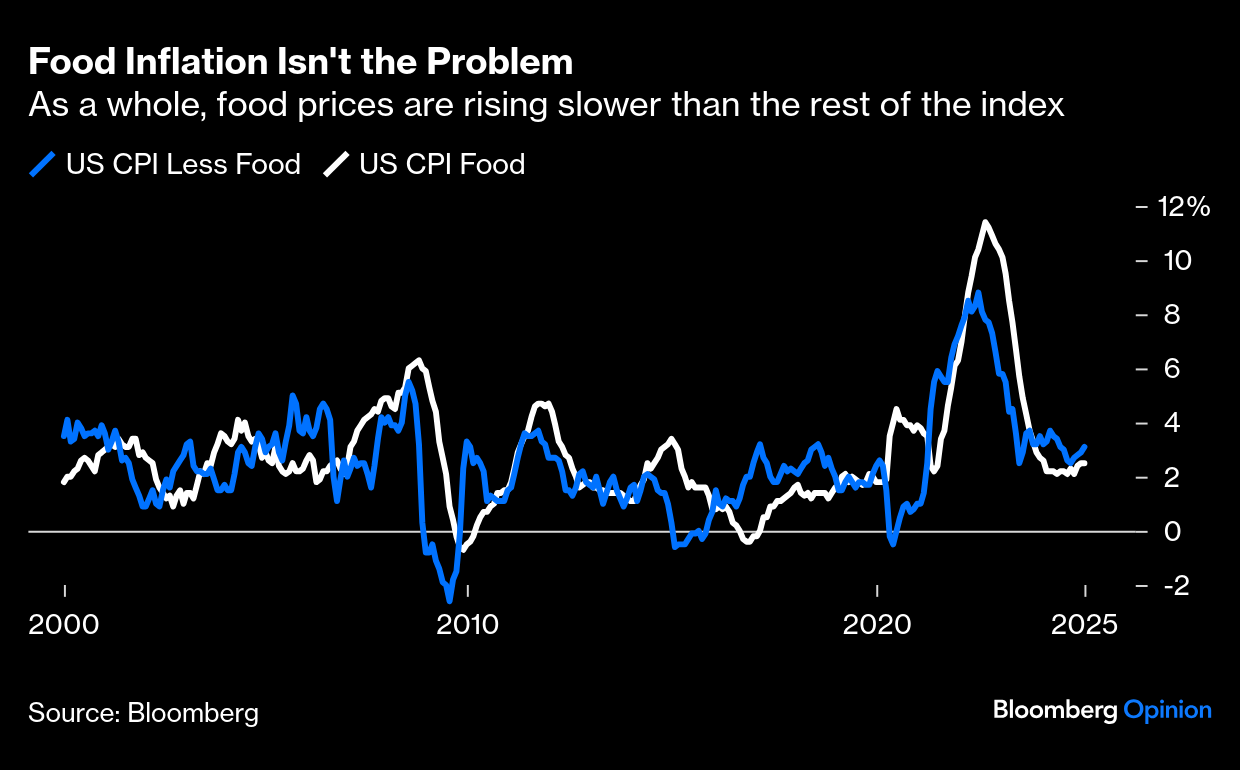

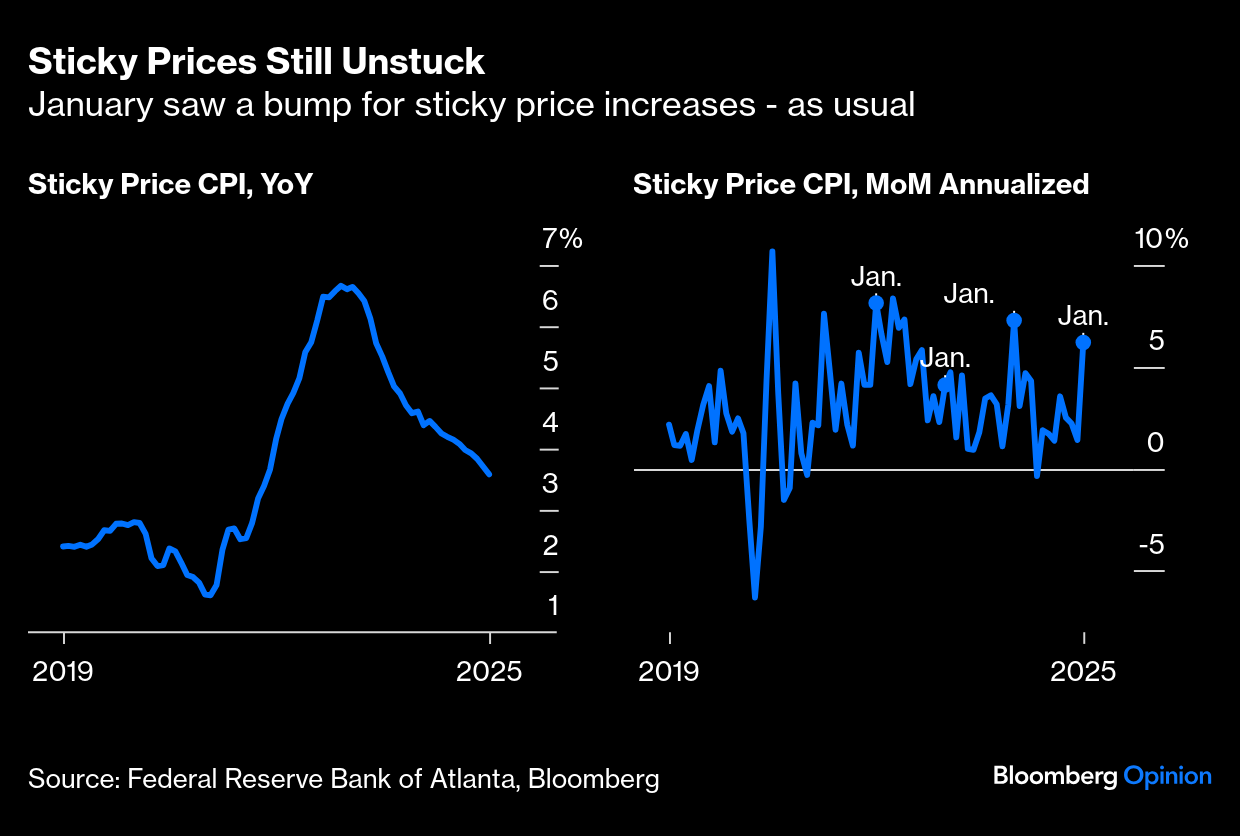

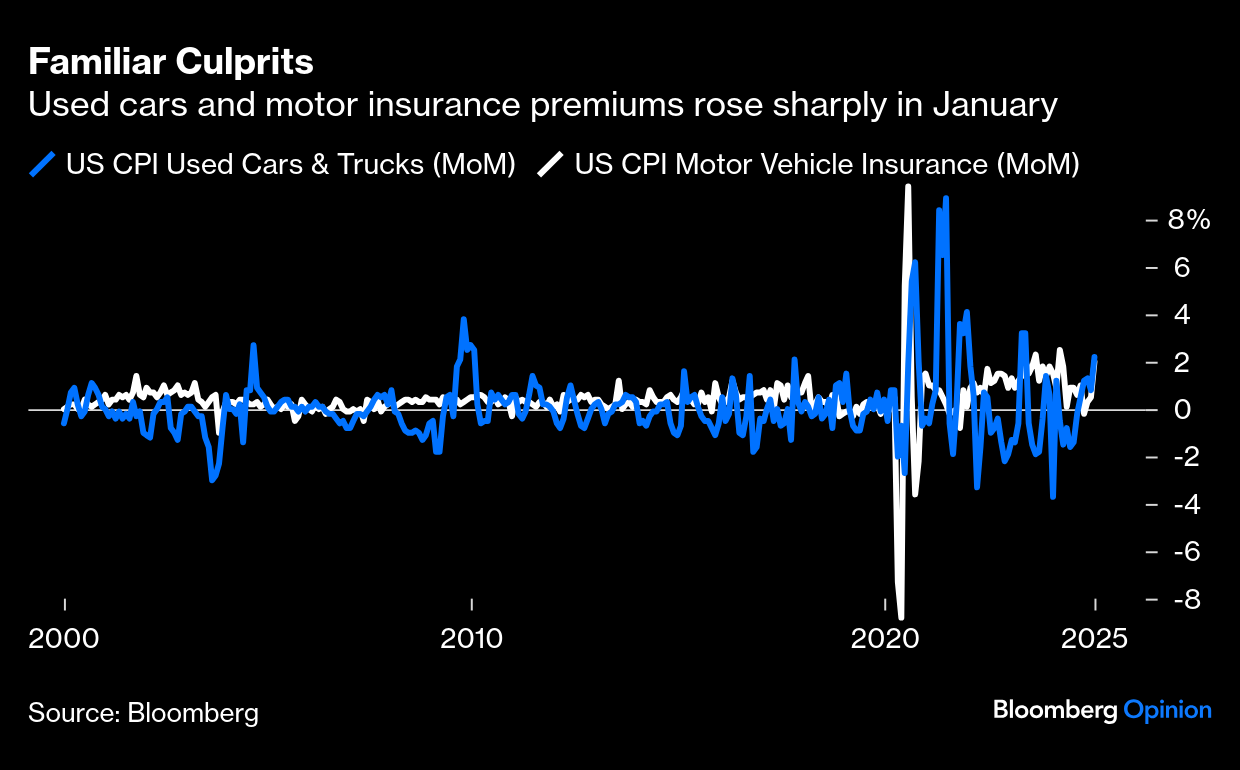

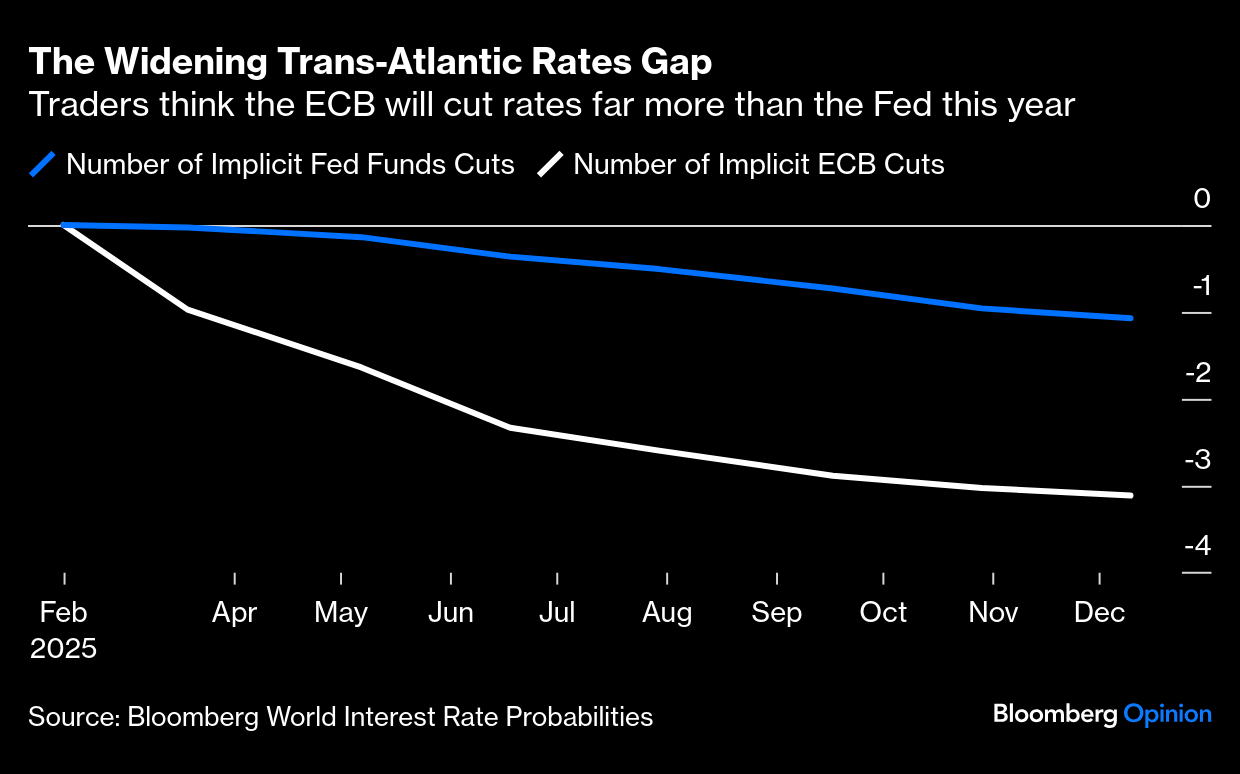

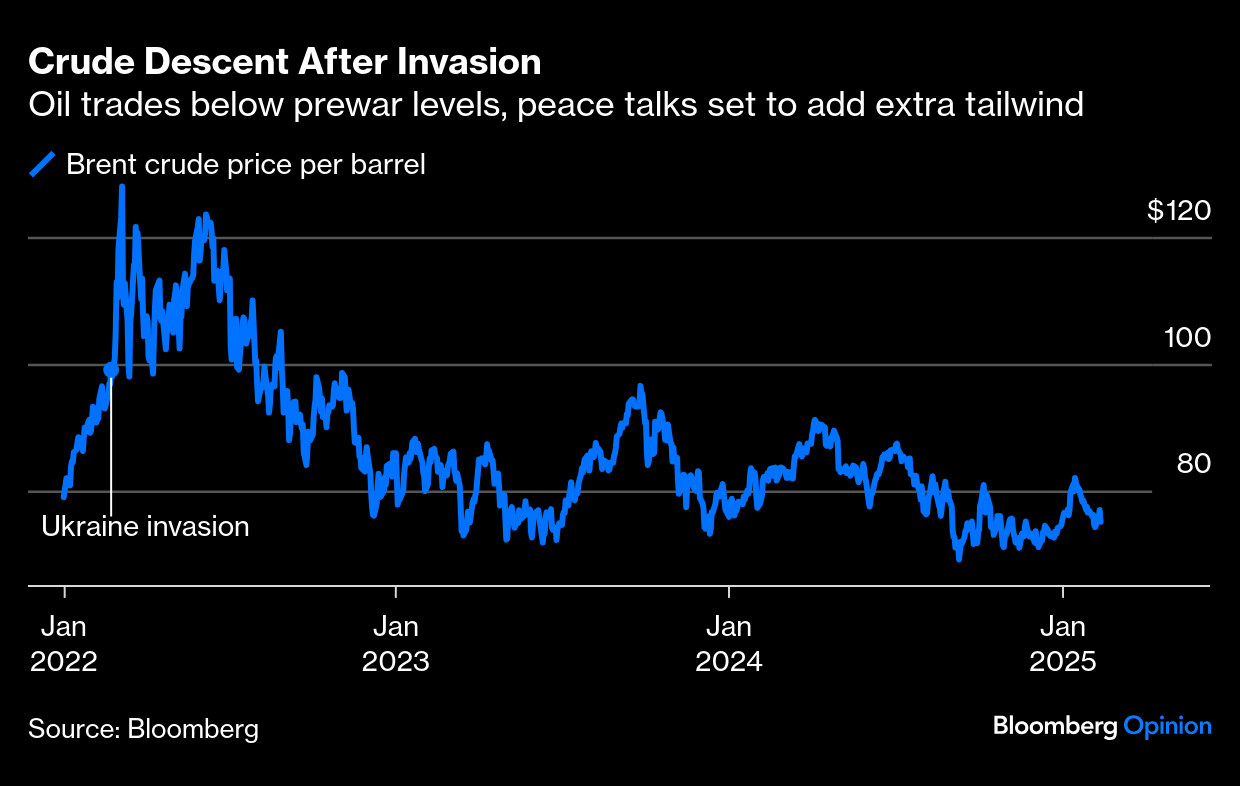

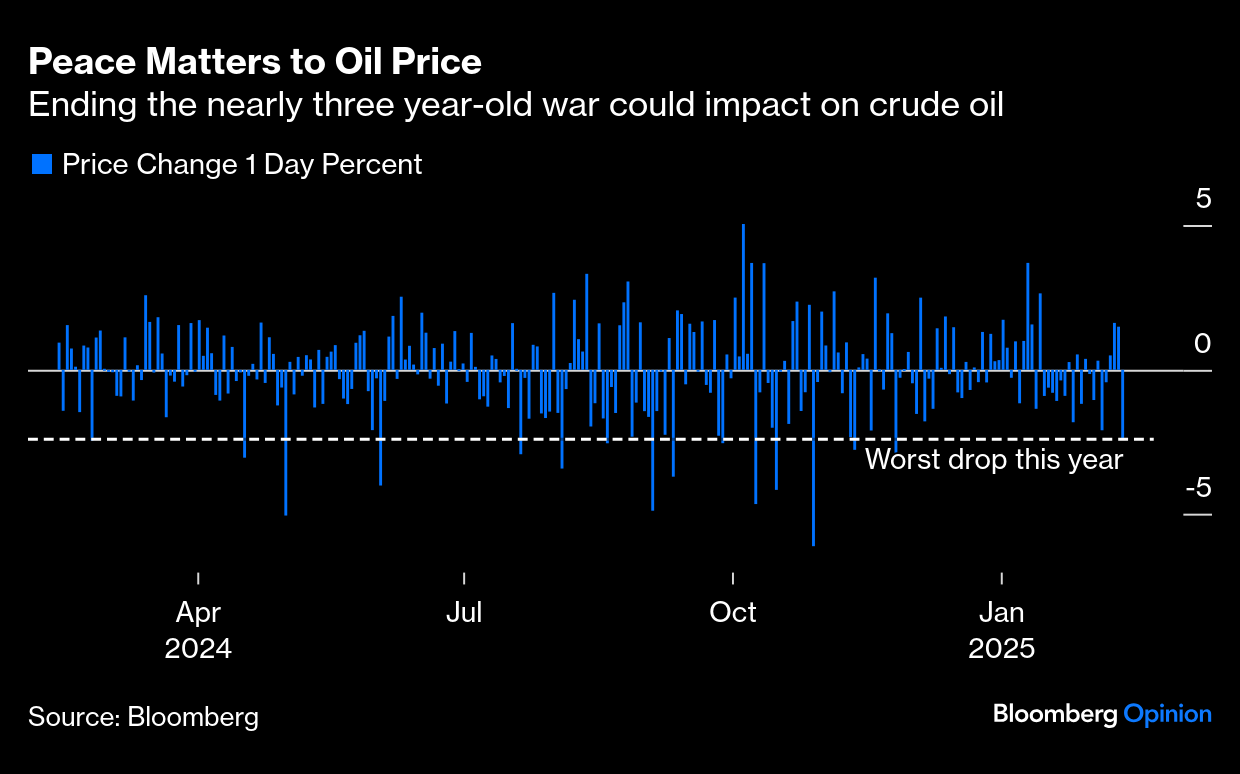

| Inflation isn't over. We already knew that, and the US consumer price index numbers for January did little more than confirm a picture that's been clear for many months. It was treated as a major shock on the markets, but probably shouldn't have been. The most significant impact came in inflation breakevens, the forecasts implied by the gap between fixed and inflation-linked bond yields. The two-year breakeven has broken above 3% (the upper range of the Fed's target) to its highest in two years, while the 10-year is also at a two-year high after reaching 2.5%. The breakeven for the five years starting five years hence, which the Fed tracks closely, remains anchored, but it's obvious that markets are growing more jumpy about inflation:  That has obvious implications for the Federal Reserve, who must wait for clear evidence that inflation is declining once more before cutting rates. That's now unlikely until much later this year. It can also be interpreted as a warning sign on trade policy. Most investors work on the assumption that tariffs would mean higher inflation in the short term, which makes the risk of rising prices look greater. The administration should also take note as the bond market can intimidate even the likes of Elon Musk and Donald Trump. However, on closer examination, the numbers (headline inflation rose from 2.9% to 3.0%, and core inflation, excluding food and fuel, rose from 3.1% to 3.3%) aren't so alarming. Breaking down into the four main subdivisions shows that the upward shift is attributable to a reversal from slightly negative to positive for energy inflation, and to a slightly smaller decline than in December for core goods. Inflation for services, long the biggest source of price rises, ticked down very slightly:  There are numerous ways to measure that have grown more familiar over the last four years. While conventional core (excluding food and fuel) rose, three other key measures — the median, the trimmed mean (excluding outliers and averaging the rest), and the Fed's "supercore" (services excluding shelter) fell. In all cases, they remain above 3% and too high for comfort, and central bankers would doubtless prefer to see them fall faster, but the trend of infuriatingly slow disinflation hasn't been reversed:  The biggest publicity has, of course, attended the price of eggs, which rose a non-seasonally adjusted 13.8% last month alone. This matters to many a household. It's not clear that it's relevant for other prices in the economy. Egg inflation has only once this century risen faster, in June 2015 during the outbreak of "Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza," or bird flu. If a disease is leading chickens to premature deaths, then of course the supply of eggs will be cut. Bird flu is back, creating much concern that it could leap to humans. (Dairy herds are also infected.) The price of eggs can be taken as a warning that this outbreak among birds is serious. It's not something the Fed or the Treasury can do anything about:  Further, although eggs are the ingredients for many dishes, they are yet to have knock-on effects on other foodstuffs. After their big increase, the next highest inflation was for frozen noncarbonated juices and drinks (5.3%), followed by instant and freeze-dried coffee (4.4% — and wholly predictable from supply problems in Brazil and Vietnam). Overall, food inflation remains stable, and lower than the rest of the index. For two years, food inflation was a major problem. That's no longer the case (unless you live on a diet of omelettes):  Another reason for calm: seasonality. People selling relatively sticky-priced products tend to announce hikes at the start of the calendar year. Thus January tends to be seasonally worse than other months. For evidence, this is the Atlanta Fed's measure of sticky price inflation. Year-on-year it is declining, though still too slowly for the Fed's comfort. Month-on-month it has just enjoyed a spike, but the chart illustrates that this is a common occurrence in January: Used cars, whose prices went ballistic in the aftermath of the pandemic, were another problem last month. The same was true of motor vehicle insurance. This isn't good, but it's important to point out that inflation in these categories was far, far worse two years ago: By the time the dust settled, bond markets had shifted significantly, with 10-year Treasury yields undergoing their biggest rise of the year so far, but US equities avoided serious damage. The Nasdaq Composite was flat for the day, while the S&P 500 dropped only 0.27%. That's impressive, as overnight index swaps now discount only one cut in the fed funds this year — not otherwise great news for equities. By comparison, the European Central Bank is expected to make three cuts: It's worth noting how radically disinflation has failed to fulfill expectations. Last September, after the Fed had made its "jumbo" cut of 50 basis points, the expectation was that the central bank would be cutting aggressively for a while to come, with the ECB trailing. Last September, overnight index swaps discounted eight cuts by the summer of this year. Two have happened already; and the market no longer thinks there will be any more: This interest rate gap strengthens the dollar against the euro (which helps to contain US inflation but also makes American exporters less competitive). That is what happened when the CPI came out: Hours later came the news that Presidents Trump and Putin had talked on the phone, and would discuss peace in Ukraine. That changed things. Trump's proposal to end Russia's war in Ukraine was always going to involve a seismic shift in US foreign policy. His predecessor's approach entrusted Ukraine to lead any peace negotiations — hence nothing about Ukraine without Ukraine. On the campaign trail, Trump bragged he would end the conflict on his first day as president. While that never materialized, it remained a top priority. His typical unconventional or what he calls "common sense" strategy put him at the forefront of the nascent negotiations after calls Wednesday with Russia's Vladimir Putin and Ukraine's Volodymyr Zelenskiy. Judging by Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth's earlier remarks at a NATO meeting, the US is already prepared to accept that Ukraine will not become a member, or return to its pre-invasion borders. That provoked pushback in Europe, but any peace roadmap is enough to ease pressure on crude oil prices. An end to the war and a sanctions-free Moscow should mean additional oil supply to an already glutted market. The onset of the war catapulted crude above $100, but that has long since eroded: Does a peaceful coexistence between Russia and Ukraine — still a long shot — matter to oil traders even with the oil price settled at a new level? Probably. Their reaction to Trump's calls shows that the "long-forgotten"' war is still on their minds: Investors in neighboring Poland and Hungary would also welcome a deal. Their respective markets have recovered from the morass that followed the invasion; rallies in recent weeks show that a meaningful resolution could make a big difference: Their currencies also fared well Wednesday, which makes sense considering the plunge after the 2022 invasion. Further progress in negotiations could likely provide an additional tailwind: Regardless of the market's reception, there's no timeline on when peace can be achieved. As Signum Global Advisors Andrew Bishop notes, Putin coming to the negotiation table is no big deal for him, and it's unlikely talks in themselves would pause hostilities: Despite President Trump's hopes for an early/upfront ceasefire — said-negotiations would likely begin with the war continuing alongside them. To the best of our knowledge, this will be the case... Trump-led peace negotiations… are unlikely to bear fruit in the foreseeable future (in 1H, in particular) — in part because Putin would be successful in "playing" Trump.

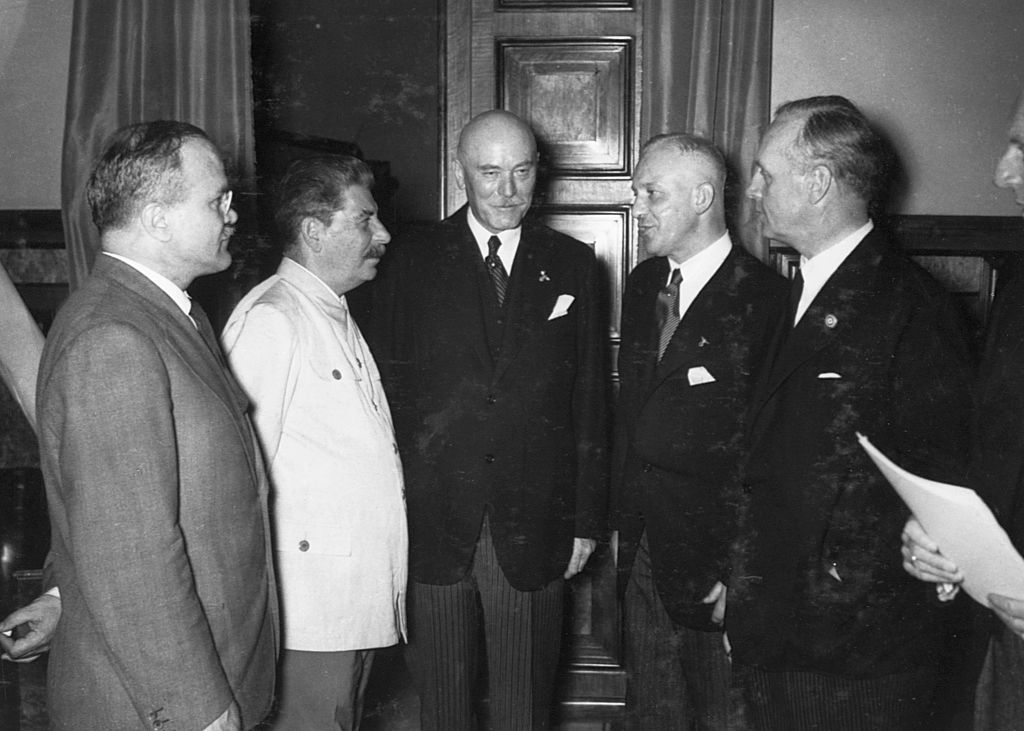

There's still much work to be done on resolving questions around the territory, reconstruction, sanctions and how to enforce the settlement. Ukraine's future, European security, and US credibility are at stake, while there are already fears that a "betrayal" of Ukraine is underway. "It's certainly an innovative approach to negotiation to make major concessions even before they have started," commented Carl Bildt of the European Council on Foreign Relations. "Not even Chamberlain went that low in 1938."  Stalin and diplomats at the signing of the non-aggression pact with Hitler. Source: Corbis Historical/Getty British journalist and commentator Nick Cohen compared Trump's overtures to the deal between Hitler and Stalin: Unlike the partition of Poland and the Baltic states in the Hitler-Stalin Pact at the midnight of the 20th century in 1939, there was no pact or deal of any kind. No advance guard of American diplomats went to Moscow to see what concessions the US could extract from the Kremlin. Trump fell over himself to give Putin what he wanted before Putin had even asked for it. The most attentive and obsequious servants know their master's wishes before their master speaks. So it is with Trump and Putin.

As it stands, Ukraine has lost far more as a result of Russia's aggression. Bloomberg Economics analysis shows that Russia's economy is 7% larger today than in prewar 2021, while Ukraine's is 25% smaller. Russia's success in shielding its economy allowed it to keep fighting and puts it in a position of strength for negotiations. In contrast, infrastructure destruction, loss of territory, and the exodus of millions of people have hit Ukraine hard. A lasting peace deal would be helpful to its economy, which lost out on areas it once dominated like fertilizer manufacturing. The world's leading fertilizer-makers tumbled on the news: An end to hostilities and bloodshed is a consummation devoutly to be wished. But an outcome that treats Ukraine's interests as secondary is unlikely to yield a meaningful peace. Peace would be excellent, as Wednesday's market showed, but the form it takes is just as important. —Richard Abbey Points of Return welcomes competition. So, let me recommend the Wall Street Journal's Markets A.M., now revamped and under the guidance of old friend and colleague Spencer Jakab. He's a brilliant financial journalist, who's been doing this for a long time after a career as an investment banker, and he's publishing at 6:30 a.m. ET, which will make his hours even more anti-social than mine (Points of Return aims to publish at midnight). It's free, at least for now. You can sign up here. And to be clear: I used to be his boss.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: - Bill Dudley: To Win the Global Money Game, America Has to Play

- Andreas Kluth: America First Is Quickly Becoming America Alone

- James Stavridis: USAID Really Does Protect Americans and Save Money

Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN . Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment