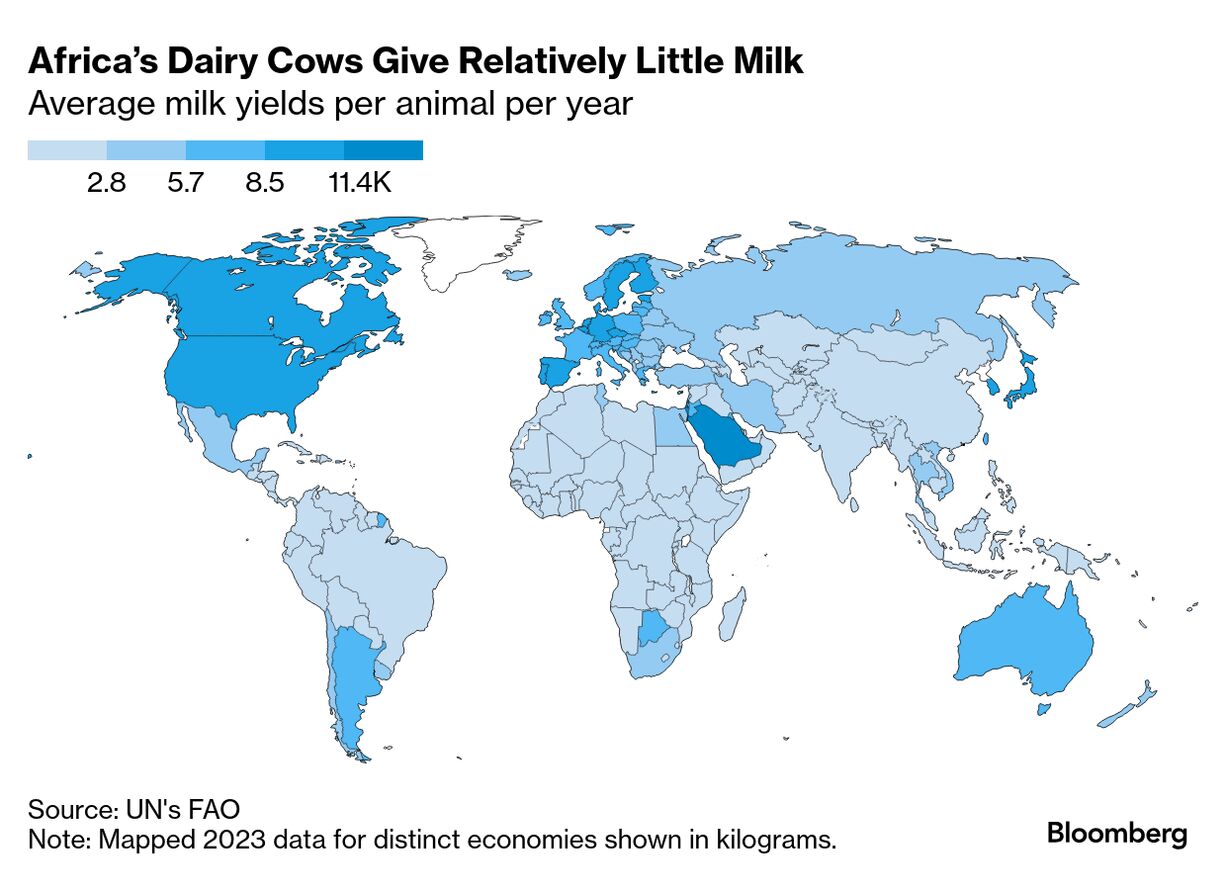

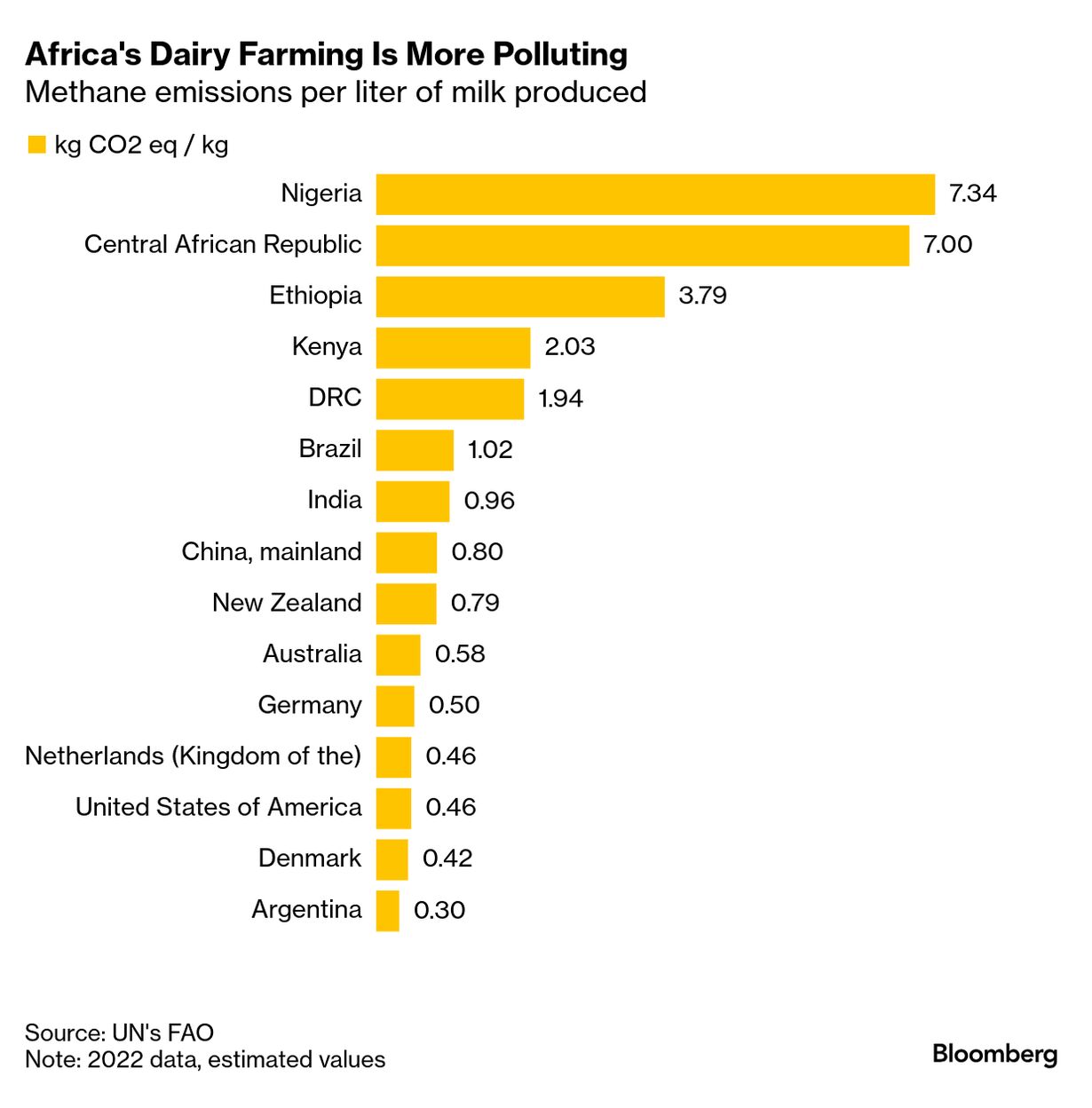

| By Agnieszka de Sousa You could call it "the other AI." As the world gets warmer, artificial insemination is gaining traction on cattle ranches feeling extra heat from climate change. In Nigeria, farmers are breeding a new generation of cows that withstand tropical temperatures and produce more milk. To do this, they're importing bull semen from the heat-resistant Girolando breed from Brazil — creating a strange new coveted commodity. And as my colleague Emele Onu and I reported this week, things look promising so far. "I will do much better with the Girolando breed," Moyosore Rafiu, a 42-year-old farmer, said in an interview. "They will survive more in our farms and I'm seeing the signs in the calves already in this farm. It's going to be a big transformation."  Dairy farmer Moyosore Rafiu at his ranch in Iseyin, Nigeria. Photographer: Tom Saater/Bloomberg Rafiu is one of thousands of farmers across Nigeria who are part of an insemination program overseen by the country's top dairy producer, FrieslandCampina, to genetically improve cattle. His black-and-white cows from European origin struggle with the intense sun and local diseases, while local breeds don't provide enough milk. African cows on average give only a couple of liters of milk a day, compared with a whopping 30 liters in the US. Heat-resistant and more productive cows are key to efforts by governments, companies and aid organizations to increase the supply of animal protein to a continent where the population is growing at the fastest rate and hunger is the most prevalent. While high-income nations are eating way too much beef and other livestock products, poorer countries with high rates of malnutrition would benefit from more meat and dairy in their diets. It's hoped that super productive cows will not only improve food security, but also help curb climate change. More milk from fewer cows means less bovine mouths to belch methane. Even though African cows make up only 4% of the global milk production, they contribute to about a tenth of enteric methane emissions. The idea is to create "sustainable intensification," said Mario Herrero, a professor of sustainable food systems and global change at Cornell University. If you have two Girolando instead of four local cows, it'll put "less pressure on resources," he said. "That is the way that it needs to happen." Read the full story on Bloomberg.com. |

No comments:

Post a Comment