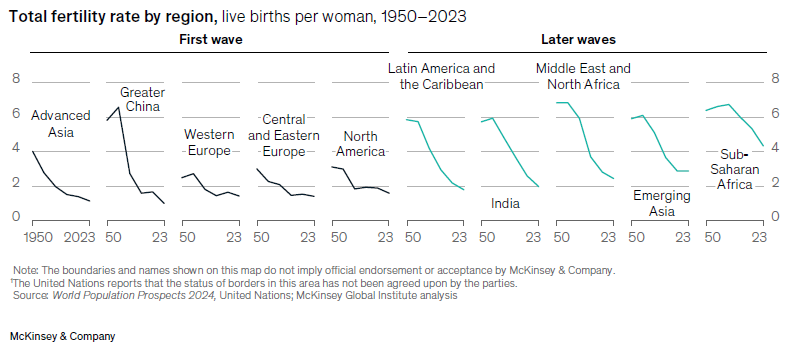

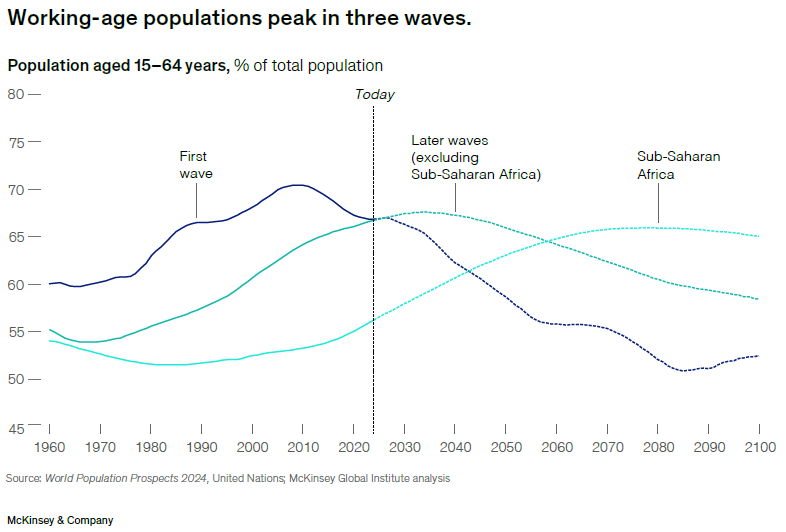

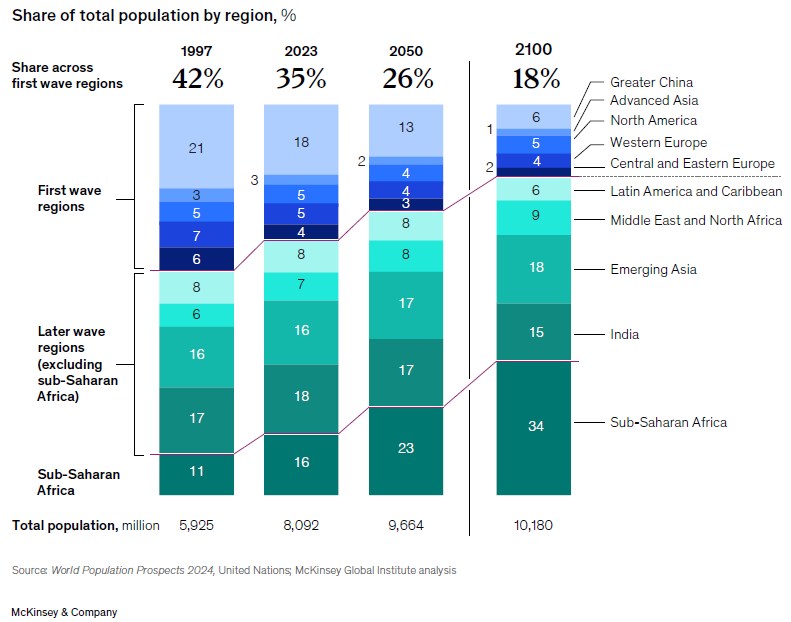

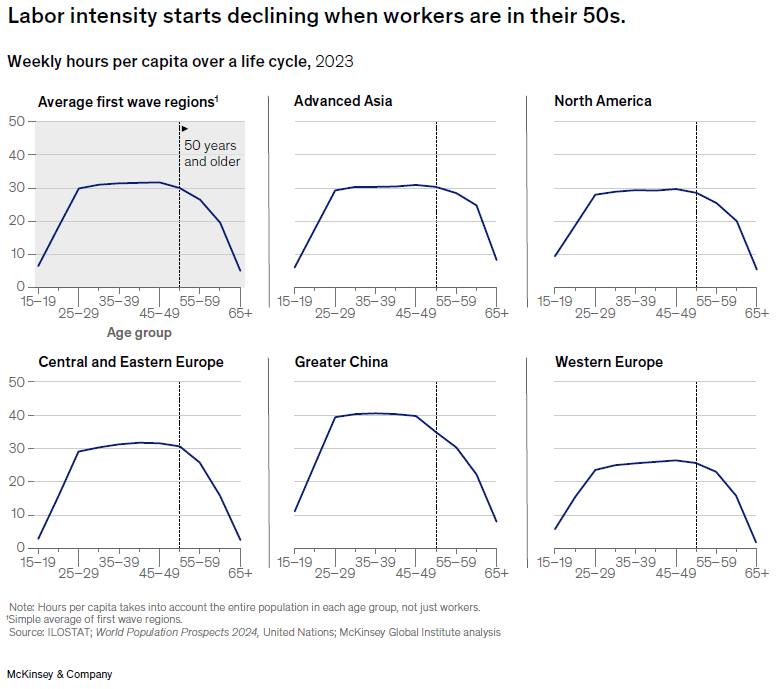

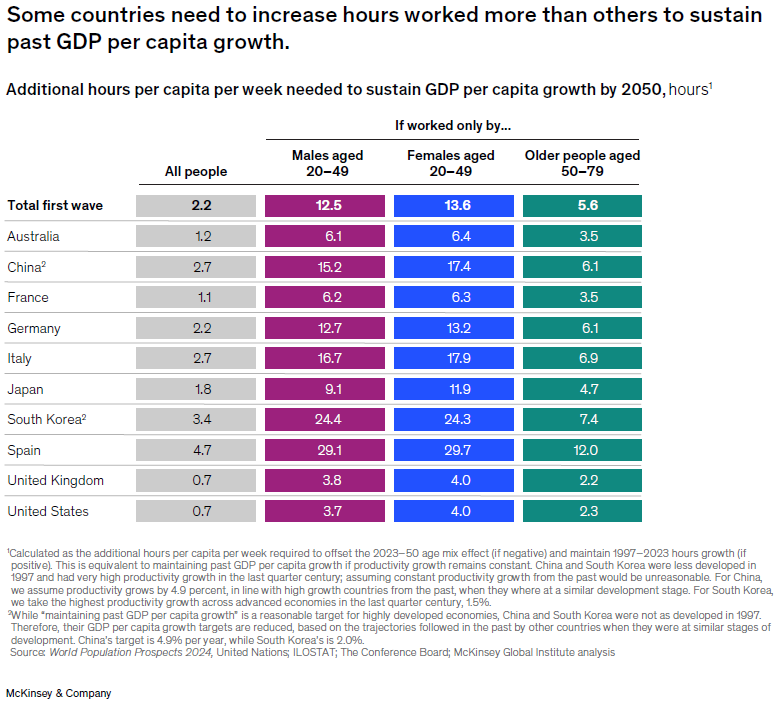

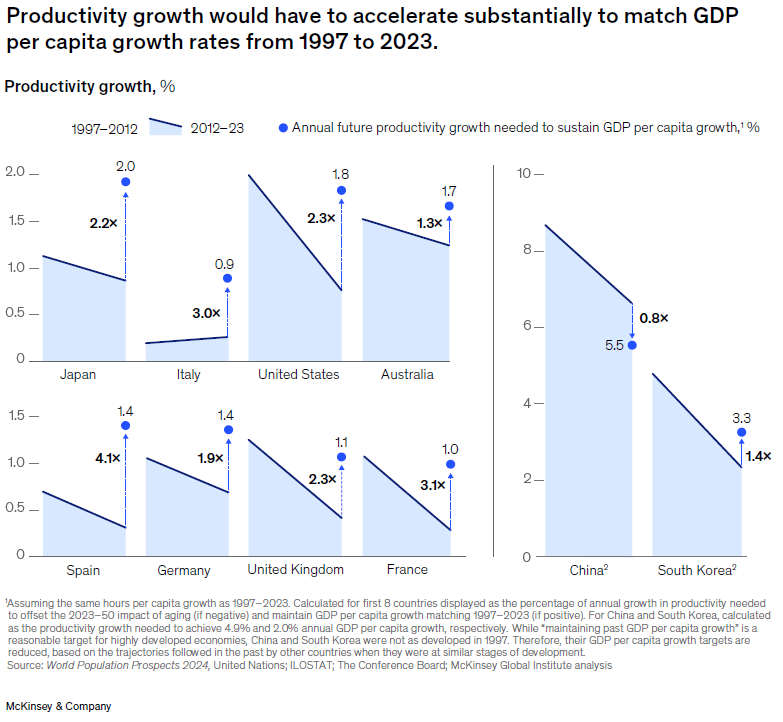

The Costs of Lower Fertility | Falling fertility is a problem across the developed world. Unlike many other risks, demographic changes can be predicted with some certainty; sliding birth rates translate directly into smaller populations ahead. That is a good thing in many ways. Two hundred years ago, the Malthusian fear was of population growth so rapid that it outstripped natural resources. But there are other ways in which it's a serious problem, which could also create opportunities for those who offer solutions. And so the McKinsey Global Institute offers a new report on "confronting the consequences of a new demographic reality." As it sounds, it's not cheerful reading, but it shouldn't be avoided. The fall in birth rates to date is universal, but far sharper in the developed world and Greater China. These countries make up what McKinsey calls the "first wave" of depopulation: More than two live births per woman are needed to sustain populations, so declining numbers are already more or less guaranteed for much of the developed world. Lower populations will mean a smaller economy, but do not necessarily entail lower gross domestic product per capita. Problems arise as the smaller cohort of people arrives at working age. This chart from McKinsey shows those of working age (between 15 and 64) as a proportion of the total. The lower this drops, the fewer workers there are to support children and the elderly. In the "first wave" developed nations, this number peaked more than a decade ago, and is now on a serious decline. In sub-Saharan Africa, workers should keep increasing as a proportion of the population for another 50 years: The chances are that the rest of this century will see some shift in economic power toward the Global South, and specifically sub-Saharan Africa. At present, the region accounts for 16% of the world's population. By the end of this century, it will have risen to 34% — almost double the population of China and the current developed world: How is the developed world going to deal with this? One obvious solution is for people to work more, both through longer hours and through waiting longer before retiring. Outside of China, where people work far longer hours per capita than in the west, that is doable. McKinsey's numbers, from the International Labor Organization, confirm that people in Western Europe at present work significantly fewer hours than in North America or the developed nations of Asia. That is in many ways a policy choice; people are glad to eschew some economic growth in return for more opportunities to enjoy life. But that deal will grow harder to sustain: However, working longer hours on its own cannot realistically deal with the issue. McKinsey did the math. This chart shows how many extra hours different groups of the population would need to work to sustain economic growth per capita at the rate to which people have become accustomed. South Koreans under 50 would have to work 24 more hours each week. For Spaniards, this number approaches 30 hours. This, surely, is not going to happen: If people want to keep working the same hours, however, economies are going to have to make some really dramatic improvements in productivity (outside of China, where productivity growth has been far higher than anywhere in the west). Across the west, most countries would need to treble their annual rates of productivity growth to keep their economy growing at the same speed. That implies a big turnaround after years of steady declines, and it's very hard to see it happening: Some combination of the above is going to be needed. People will have to work longer hours and retire later, which will mean reversing generations of gains made by workers. Improvements in longevity and health care would help this to happen, but the passionate objections to attempts to raise retirement ages (most dramatically in France, but nobody wants to have to wait longer for their pension) show how difficult this will be. That leaves, it seems to me, two obvious conclusions: - Productivity has to improve somehow. That's easier said than done, as the history of the last few decades makes clear, but the fact that it's growing so urgent to find a way to get each worker producing more does suggest that the excitement over artificial intelligence has some justification. AI really might liberate a lot of people from jobs altogether, and boost others' productivity. It does make sense to invest a lot in a technology that has true potential to solve the productivity problem.

- Heavy emigration from sub-Saharan Africa makes immense sense. The region will be producing more workers, who can fill the gaps emerging in the labor forces everywhere else. The region has made great progress in eliminating extreme poverty, but is much less far forward in the attempt to build a prosperous middle class. Immigrant remittances, and the job experience to be gained overseas, would be just what the region is needing. Solving the problems caused by falling fertility in the developed world while bringing some prosperity to the region where it is most conspicuously lacking would make eminent sense.

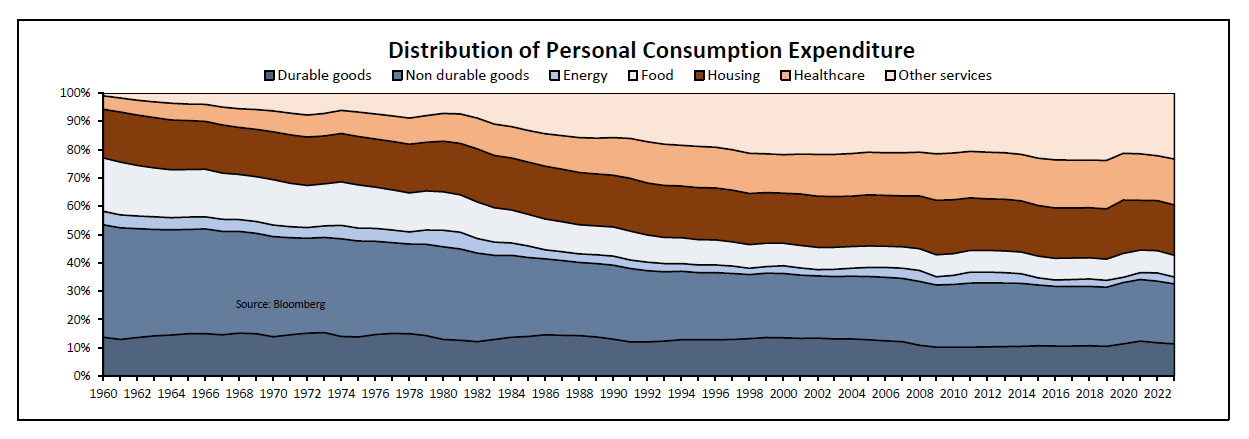

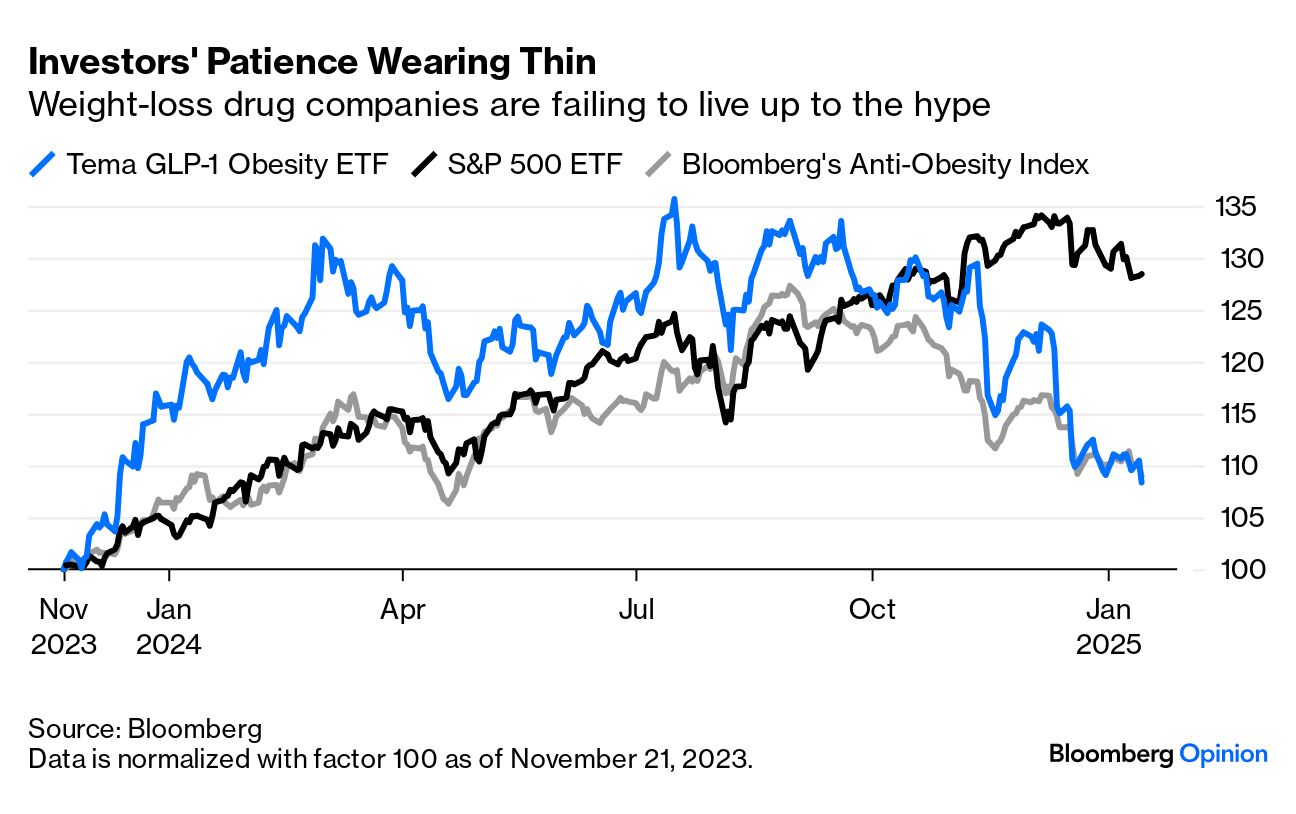

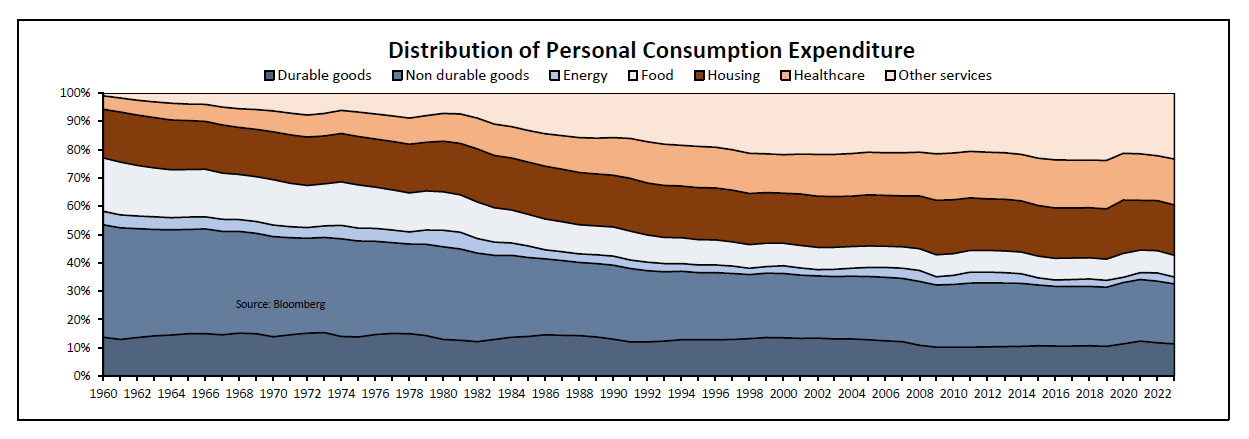

Of course, western populations do not at the moment seem ready to encourage an influx of African migrant labor. Quite the reverse. But the problem can only intensify, and that will force us all into examining some unpalatable alternatives. From Blockbuster to Lackluster | Obesity drugmakers are fast losing their aura. Their recent stock market performance has been anything but a blockbuster, as what was regarded as the biggest break in medicine since Covid-19 vaccines has struggled to live up to expectations. Eli Lilly & Co., which makes the obesity and diabetes drugs Zepbound and Mounjaro, is the latest to disappoint investors. For the second quarter in a row, the Indianapolis-based pharmaceutical company's revenue fell short of analysts' estimates, and its shares tanked on the news, bringing the S&P 500 Healthcare index down with it. Lilly's 7.5% fall was its worst since 2021. The market's response was symptomatic of growing intolerance for drugmakers' inability to turn hype into cash. It didn't matter that the company predicted the revenue miss in its third-quarter earnings call. The Tema GLP-1, Obesity & Cardiometabolic ETF, which invests in weight-loss drugmakers, has been on a slide since September: This is not just about Eli Lilly, and the disenchantment appears to be global. Bloomberg's obesity index was initiated in 2015, and includes manufacturers of diet foods as well as pharmaceuticals companies. Lilly has only the fourth-largest weighting. Its recent fall has been spectacular: Interestingly, Eli Lilly's troubles came after the company pumped over $20 billion into boosting supply and fixing the perennial shortages that have annoyed consumers. The company is left with an unexpected surplus of the drugs. Now that there is no longer a shortage, Chief Executive Officer Dave Ricks' explanation that the miss was down to an inadvertent exaggeration in its demand forecast makes sense — but doesn't fully explain why the expected "bump up" failed to materialize. The issue has macroeconomic implications. Vincent Deluard of StoneX suspects health care inflation is beginning to take a toll — even disrupting the Federal Reserve's 2% inflation target. The sector accounts for 20% of GDP and is experiencing near double-digit inflation. He argues that other prices would have to stay flat to accommodate the rising health-care costs and still meet overall Fed targets. Anti-obesity drugs raise the possibility of reining in some of the massive spending on treatments for ailments caused by obesity. This StoneX chart shows that health care's share of personal consumption expenditure has risen from 4% in 1960 to 17%. The consumer price index for health-care services has increased by 5.5% annually over the period. Deluard's analysis found that non-durable goods, whose share of PCE dropped from 40% to 20%, experienced inflation of just 2%. So, much is riding on these drugs:  Resolving the accessibility problem should go a long way. Obesity is an epidemic in the US, and elsewhere in the western world, and weight-loss drugs' total addressable market, expected to reach $100 billion by 2030, is enough to spur innovation. Consumers' voracious appetite for the product could usher in breakthroughs such as oral pills as soon as this year. Currently, the field is dominated by injectables, which many people understandably dislike. The CEO of Structure Therapeutics Inc., Ray Stevens, whose company is trialing anti-obesity pills, argued to Bloomberg News that they would be a game changer by encouraging patients to use them for longer in a "maintenance phase" after they had lost weight: Accessibility is a major problem: 85% of people discontinue injectables after two years. 65% discontinue after one year. We think oral pills will continue the maintenance phase of people. We don't want to see people lose weight and then experience a yo-yo effect — gaining and losing weight repeatedly. That's not healthy, either. We think oral pills will be used not just in the maintenance phase for a chronic disease, but also prescribed by primary care physicians from the very start.

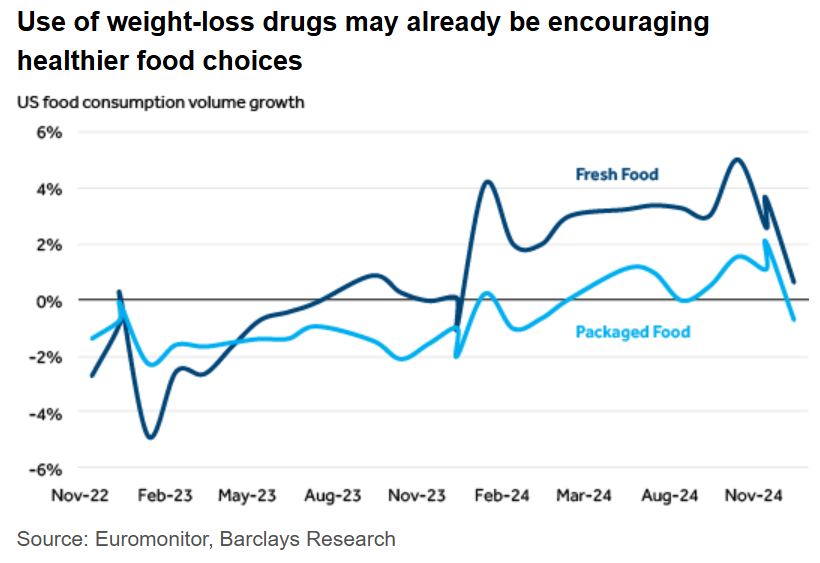

Almost all the major drug makers are holding trials of oral anti-obesity drugs. While initial results have been mixed, they still encourage the prospects that they can be used to reach more people. However, such large-scale adoption of highly effective weight-loss drugs could signal trouble elsewhere. Analysts at Barclays say the ramifications go beyond the pharmaceutical sector, as they can influence how people eat and drink and the ailments they may face. Beverage makers, packaged food companies, restaurants, medical equipment makers, and their investors are watching developments. This Barclays chart suggests that rising use of GLP-1 drugs could be prompting consumers to shift from processed to fresh food: —Richard Abbey A movie recommendation. Netflix has the latest Wallace & Gromit movie, Vengeance Most Fowl. You should watch it, because it's a work of genius. Like all the previous works in the Plasticine oeuvre, it's hilariously funny and it's also a great thriller. It's survived the passing of Peter Sallis, the original voice of Wallace, and has incorporated improvements in computer-generated animation without undermining the charm of the Claymation figures. How a Plasticine dog who makes no sound can possibly show as much emotion as Gromit does merely with a move of his eyes and his ears remains a wonder of our times. It's feature-length and you'll love it.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN . Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment