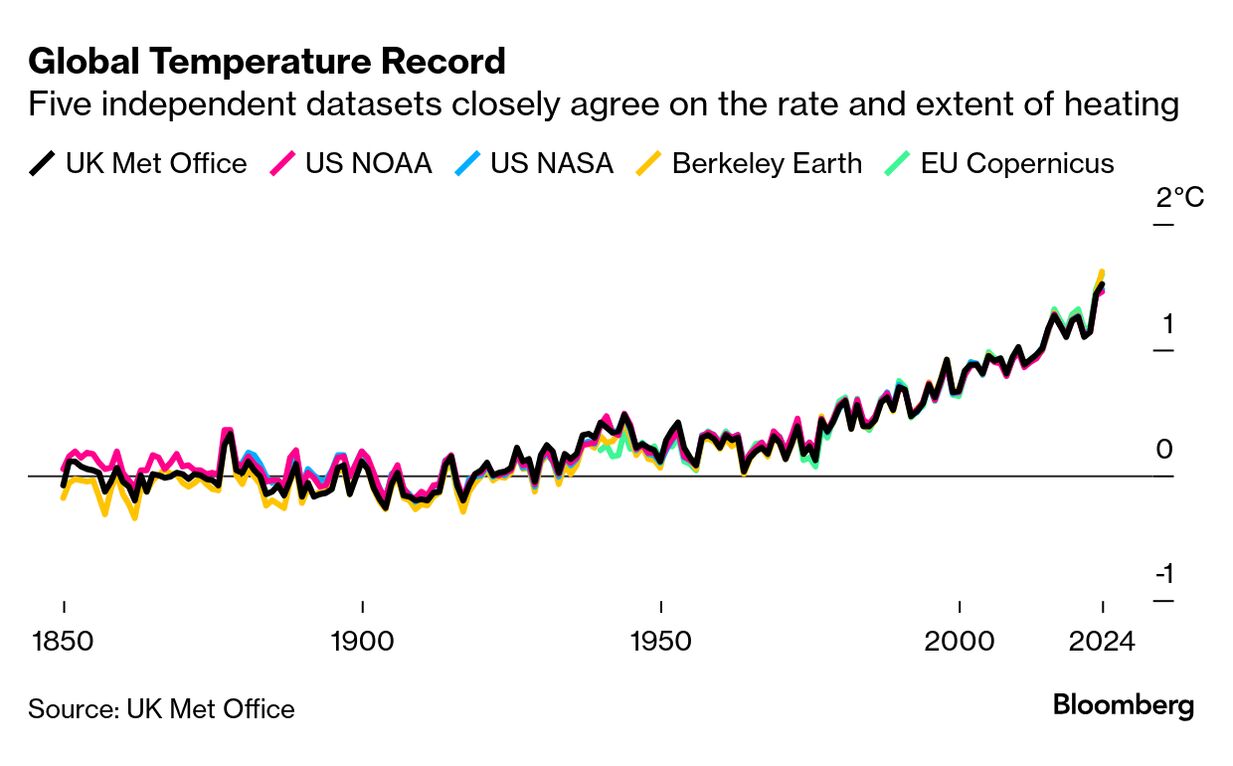

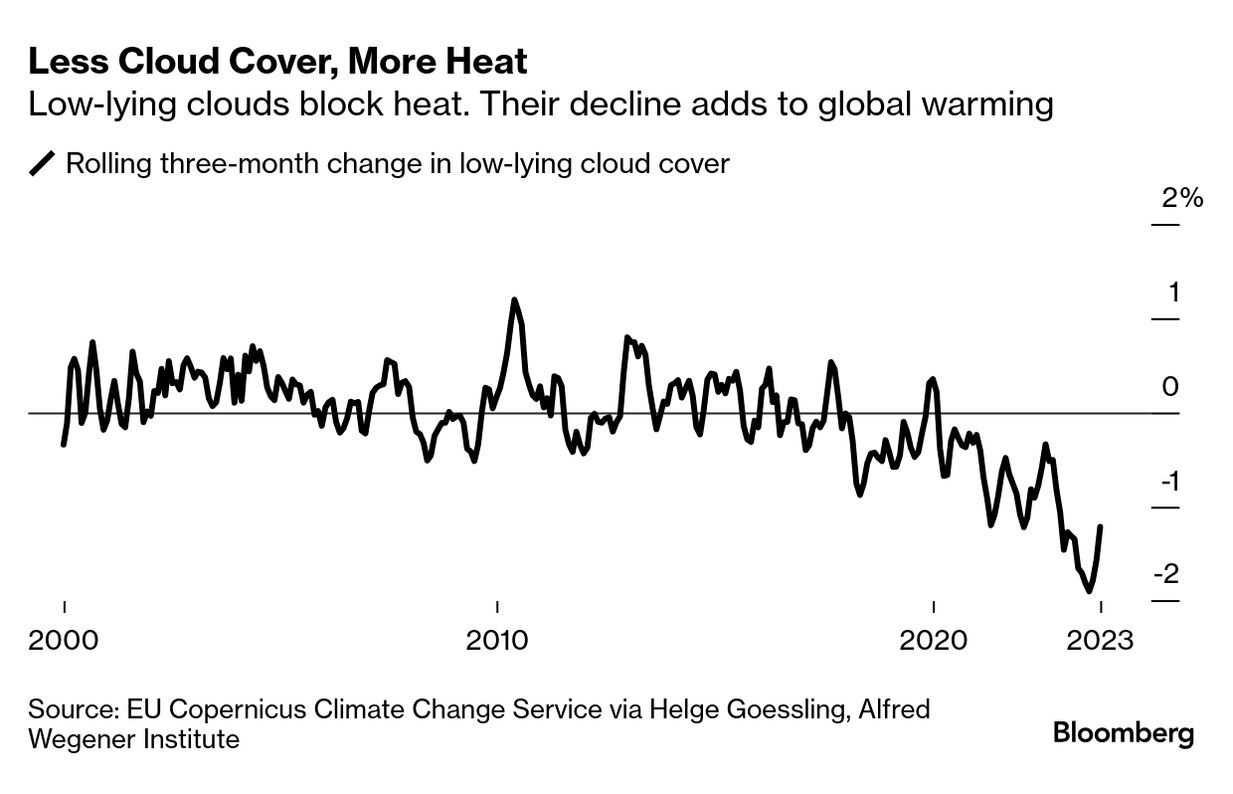

| By Eric Roston The global average temperature reached 1.5C above pre-industrial levels in 2024, according to five independent science agencies. It's the most potent sign yet that countries are failing to meet a Paris Agreement goal of limiting global heating to that amount long-term. No one on Earth experiences a global average: Wherever they live, they might experience record heatwaves and rainfall, intensifying cyclones or — evidenced by today's ongoing tragedy in Los Angeles — destructive wildfires. So what does it mean that scientists found 2024 to be above 1.5C? Here are the main takeaways. 1. Most countries are making the problem worseOver the past decade, 200 nations and thousands of cities, companies and investment firms have pledged to organize their climate plans around the Paris Agreement's goal of "pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5C." Scientists understand that limit to mean 1.5C (2.7F) of warming above the pre-industrial climate over many years, conventionally two decades or more. So one year doesn't signal complete failure, but it does indicate that's probably coming. In its report on 2024, the nonprofit Berkeley Earth said the quiet part out loud: The Paris target of staying below 1.5C at this point "is unobtainable," according to Berkeley Earth Chief Scientist Robert Rohde. But 1.5C is largely a political target – the number that diplomats nominally agreed to a decade ago – and not a physical hard limit. What's most important to keep in mind is that every tenth of a degree of warming that can be avoided will limit the damage of climate change. And every metric of ton of carbon dioxide emitted will bring more warming. The world puts out more than 100 million tons a day. Although a few countries have cut their carbon pollution significantly, global emissions haven't peaked yet. 2. It's hotter than it should be…Many scientists have spent months fretting that climate change is accelerating. The margins by which 2024 and 2023 broke the global heat record are flabbergasting. Usually, it's straightforward to project a year's temperature. Greenhouse gas pollution sends a steady signal. What determines any year's temperature is therefore the short-term weather. When there's an El Niño, or warm phase, a year is more likely to set a record, as the last two did. But factors other than greenhouse gases and natural variability are at play. 3. …and scientists aren't sure why. The extra heat of 2023 and 2024 sparked a worldwide whodunit. A southern Pacific volcano in early 2022 shot a record amount of heat-trapping water vapor into the upper atmosphere. Analyses first blamed that for the phenomenal 2023 record. But volcanoes also send up sulfur aerosol particles that have a cooling effect. Net-net: The much-debated volcano was a red herring. Sulfur aerosols are a toxic pollutant and pour forth from fossil-fuel power plants and transportation. Since international shipping regulations requiring low-sulfur fuels went into effect in 2020, scientists have seen an 80% drop in related sulfur aerosol emissions. That benefits human health, even at the short-term cost of temporarily higher temperatures. Similarly, 70% cuts to China's sulfur pollution since its 2006 peak are reducing the overall atmospheric load — and for a time putting upward pressure on the temperature. 4. The recent heat could be a blip. Or it could be an acceleration.Greenhouse gas emissions were responsible for almost 80% of 2023's heat record (1.48C above the pre-industrial average, according to the EU's Copernicus Climate Change Service). El Niño added less than 5%. But 0.2C of the heat budget was missing, and that's not normal. Long story short: German researchers found it among the clouds. A hotter than normal North Atlantic ocean led to their conclusion, published in December, that more solar energy was reaching the surface because reflective low-lying clouds have been disappearing. Why that's the case — and more important, whether it signals a pace of warming even more dangerous than models projected — remains unsettled. 5. What happens in 2025? The average temperature will continue to rise with emissions, raising local temperatures and other extreme-weather risks. That alone is enough to expect 2025 to land in the upper echelon of hot years, with records dating back to the mid-19th century in most datasets. The last 10 years are the hottest on record. All but one of the hottest 24 years occurred this century (1998 saw a powerful El Niño. It's now ranked 18th). With the rise of a La Niña, the odds that 2025 will out-heat 2024 or 2023 are vanishingly small. But that climate change signal — and any X factors accelerating at the margins — aren't to be discounted: Two research groups expect this year to come in third. Read the full version of this story on Bloomberg.com. |

No comments:

Post a Comment