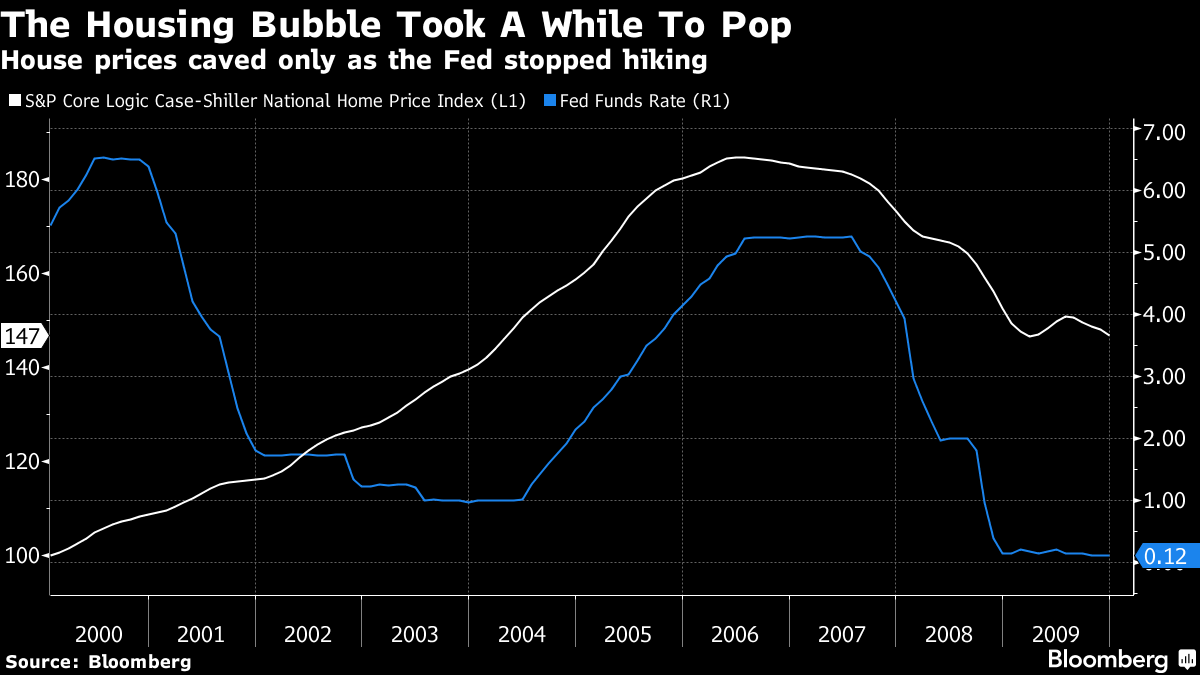

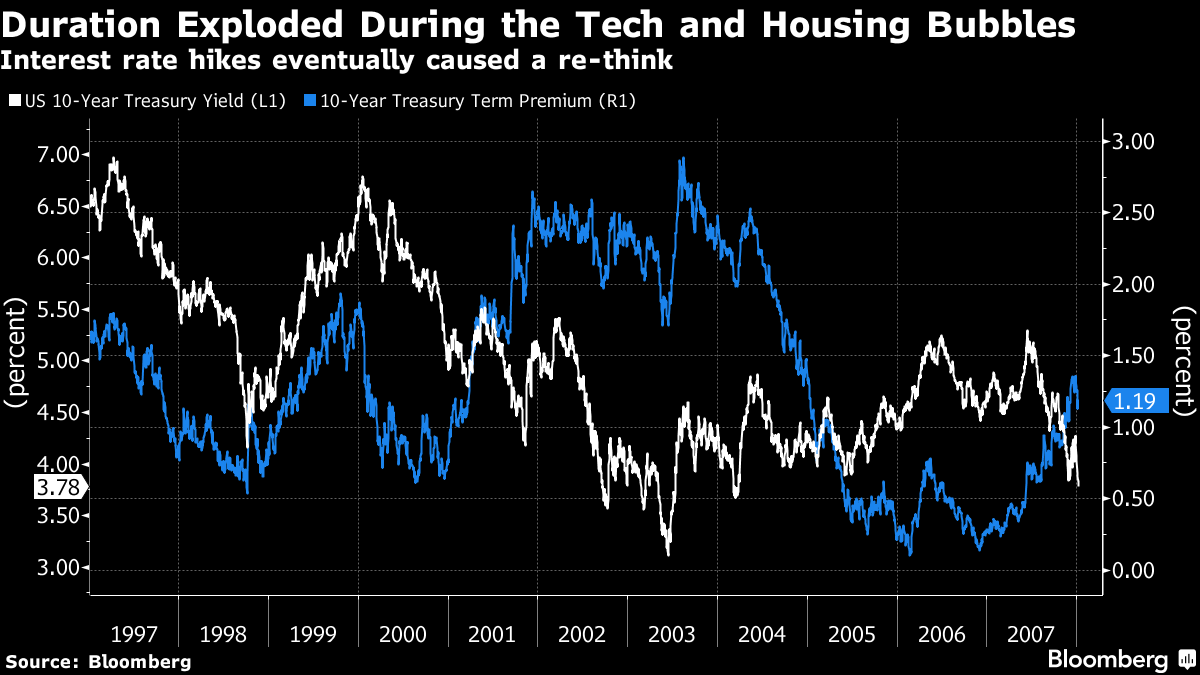

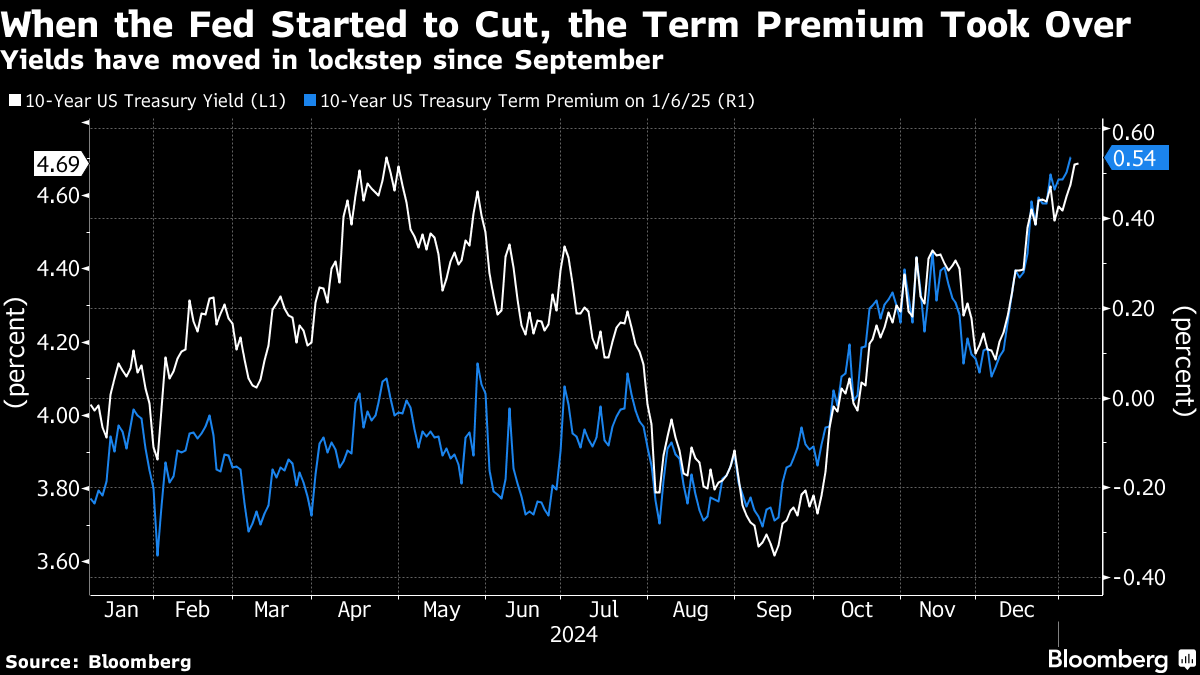

| Let's start with the overlooked point that higher interest rates are great for savers and lenders. To put it simply, for higher fed funds rates to have a restrictive effect, the financial distress, the rising cost of debt for borrowers and the resulting curtailing of investment, has to override that extra income to savers and lenders. Essentially the Fed has to create financial distress. I think this is perhaps the most important — and most overlooked — fact about this particular rate cycle because a lot of people think higher interest rates are always restrictive. But that's not true at first. The private sector is a net receiver of interest due to government deficits. So, initially higher interest rates stimulate the economy through the interest income channel. Think of higher rates as a gift, a handout, to rich people who disproportionately benefit as savers and lenders. It's only when those rates are high enough to put business and household debtors into dire straits that the restrictiveness comes into play. And in today's context, so many companies and households have locked in favorable debt repayment terms that, in aggregate, the benefits of higher savings rates and higher bond returns continue to outweigh any financial distress. Look at the mid-noughties and the housing bubble, for example. The Fed started hiking rates in mid-2004. But that didn't mean instant financial distress. House prices kept rising for another two years, until mid-2006, just as the Fed paused. As the distress mounted in 2007, the Fed started cutting. It was too late because the financial distress overwhelmed everything else. 'Term premiums' matter more than we think | So what happened? As a bull market progresses, people don't just get enamored with the market darlings of the day, they take on all manner of risks by essentially 'extending duration.' Extending duration is just a fancy way of saying being comfortable with not getting paid back until much later in the future. It's like lending a friend 100 dollars and getting it paid back, say, three years from now instead of in three months. A love affair with duration means buying riskier stocks with high growth potential whose potential profits are all backloaded into the distant future. Think Tesla, whose stock price represents 180 times its last twelve months' of profit. Loving duration also means putting money into the stocks and bonds of companies with less assurance of getting paid back, like the ones that went bust in the Internet Bubble, for example, or lower-rated junk bonds whose yield have plummeted since August. The easiest way to visualize what happens with duration is to look at the premium people extract from the US government for investing in longer-maturity Treasury bonds. When that 'term premium' goes down, it's a clear sign that investors have fallen in love with duration and a bull market is underway. As the economy stuck a soft landing in the late 1990s, term premiums collapsed, lowering bond yields, which helped make risky assets more attractive. A bull market followed. Then the Fed started to raise interest rates. Suddenly, the love affair with duration started to unravel — immediately in the Treasury bond market, but a year later for all long-duration assets including stocks. When the Fed realized a recession would ensue, it cut rates and the term premium declined again. But a difficult recession meant term premiums rose again, forcing the Fed to cut rates even more aggressively. Only when 10-year yields bottomed in 2003 did premiums fall again, helping to fuel the housing bubble. Just as in the late 1990s, the 10-year term premium plummeted as the economy prospered. But so great was the euphoria that it kept declining even as the Fed started hiking rates, forcing the Fed to raise rates more than it wanted. In 2005, Fed Chair Alan Greenspan even called his inability to get long-term interest rates to respond to rate hikes a conundrum. But it was all about the animal spirits unleashed as Americans fell in love with long duration assets. Eventually though, the term premium stopped falling. And that's when the bottom fell out of the housing market. |

No comments:

Post a Comment