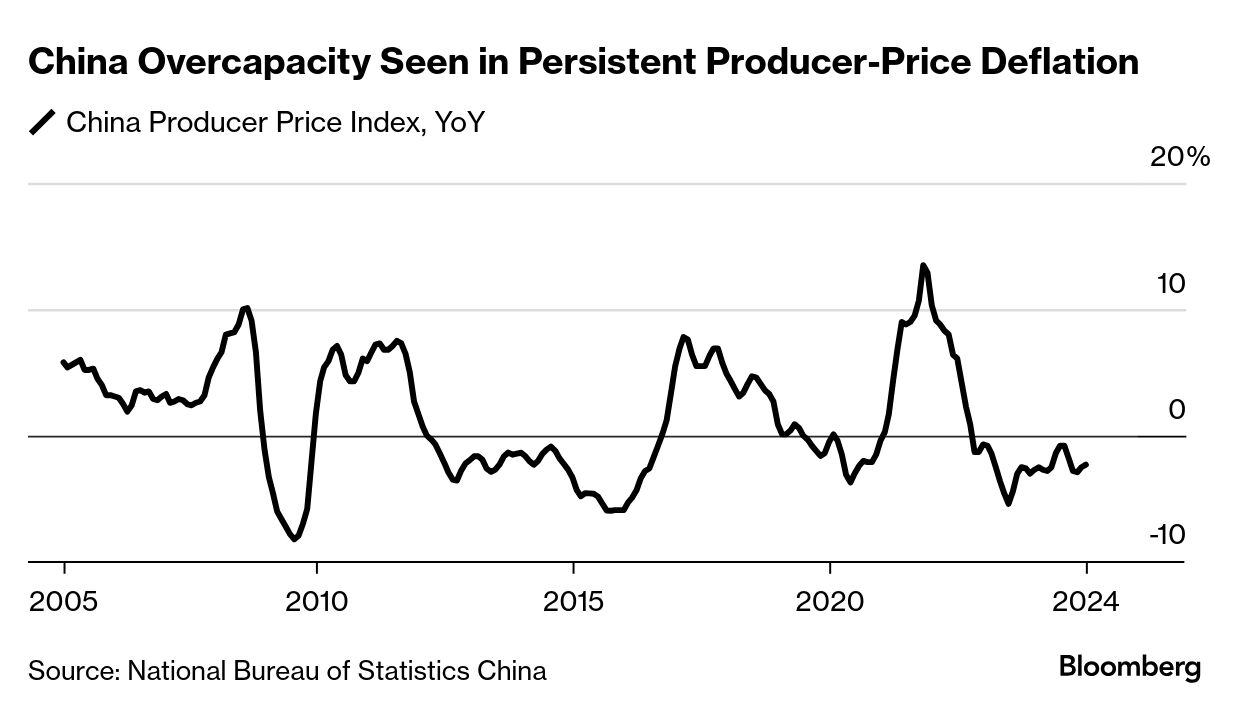

| China's top economic planning body this week released a new set of guidelines for battling protectionism. But it had nothing to do with the US or Donald Trump. In fact, the document was all about the latest effort to dismantle domestic barriers to Chinese businesses—shining a light on one of the less-covered structural weaknesses of the world's second-biggest economy. For all of China's vaunted reforms and opening up to the outside world, it never overhauled its own domestic economy to stop provinces and cities from unfairly giving their local firms a leg up. The acknowledgement that domestic protectionism remains rife in one sense validates long-standing foreign criticism of China as a rigged system. The US Treasury's top international official, Jay Shambaugh, highlighted last year the problem of subsidies "especially at local and provincial levels" in China. The hope among China's policymakers is that bringing down local barriers will reduce logistics costs, promote competition, boost productivity and improve overall business confidence. But the State Council's own reference in a Jan. 7 statement to the concept of a unified market being "not new in China," dating back to at least 2013, suggests observers may not want to hold their breath for meaningful change.  Shoppers walk down Nanjing East Road, a busy retail street, in Shanghai Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg This week in the New Economy | Local Chinese officials won promotion for decades by pursuing growth in their region and boosting tax revenue. That gave them incentives to support local employers and keep out competitors from other regions—through means including tax benefits, subsidized interest rates, regulatory enforcement, government procurement preferences, resource allocation and licensing rules. Each new missive from President Xi Jinping and his predecessors, on things like building up solar power, developing the battery industry, or innovating electric vehicles, served as a fresh push to build forward local production. "Each province wants its own industrial champions, providing tax revenues, opportunities for personal gain, and attainment of local officials' evaluation targets," Charles Parton, a China specialist at the UK think-tank Council on Geostrategy, said in a report last year. "This regional protectionism is a significant part of the reason for overcapacity issues" in China, he wrote. That oversupply relative to subdued domestic demand can be most easily seen in the producer price index. Factory-gate prices slumped 2.3% in 2024, and the index has been in deflation for 27 straight months. A broader price gauge, the GDP deflator, has seen the longest sustained contraction since the 1990s. China's domestic protectionism also effectively incentivized exports. Companies may find it easier to deal with foreign customers and investors than having to contend with provincial and municipal officials elsewhere in China. But the outside world is turning less friendly to Beijing. Not only is Donald Trump, the self-identified lover of tariffs, heading back to the White House, but the European Union has started levying them as well, calling the scale of its trade deficit unsustainable. That increases the pressure on Xi and his aides to strengthen the domestic economy. Some China economists have been enthusiastic for this unified-market initiative. He Weiwen, a senior fellow at the Center for China and Globalization research group in Beijing, likened its power to the unifying force of German states from 1815 to 1871. The German economy "boomed" after it dismantled its internal barriers, he said. But He was speaking almost three years ago, after the State Council issued guidelines to "speed up" a unified national market. Which speaks to the challenges China is apparently facing in actually implementing its wishes. Tellingly, this week's latest announcement failed to spur the usual wave of notes from economists at investment banks typically seen after Chinese economic-policy moves. The latest guidelines, published by the National Development and Reform Commission, set out requirements on a broad range of issues, from safeguarding property rights and fair competition to the rules governing transportation and telecommunication networks, land trading and product standards. There will also be a public complaints channel where companies can name and shame those who aren't complying with the new push. Along with establishing as a performance metric the progress officials make in advancing the initiative, the latest measures "will ultimately help resolve some persistent operational issues," according to Trivium China. But the research group cautioned foreign companies against concluding that any of this would do much to address broader challenges. In other words, perhaps something less memorable than Germany's 1871 unification. —Chris Anstey Bloomberg House at Davos: Against the backdrop of the World Economic Forum on Jan. 20-23, Bloomberg House will be an unparalleled hub where global leaders converge to chart a path forward. Join us for breakfast, afternoon tea or a cocktail. Meet thought leaders, listen to newsmakers, sit in on a podcast taping, have a candid conversation with our journalists and help us identify the trends that will impact the year ahead. Request an invite here. |

No comments:

Post a Comment