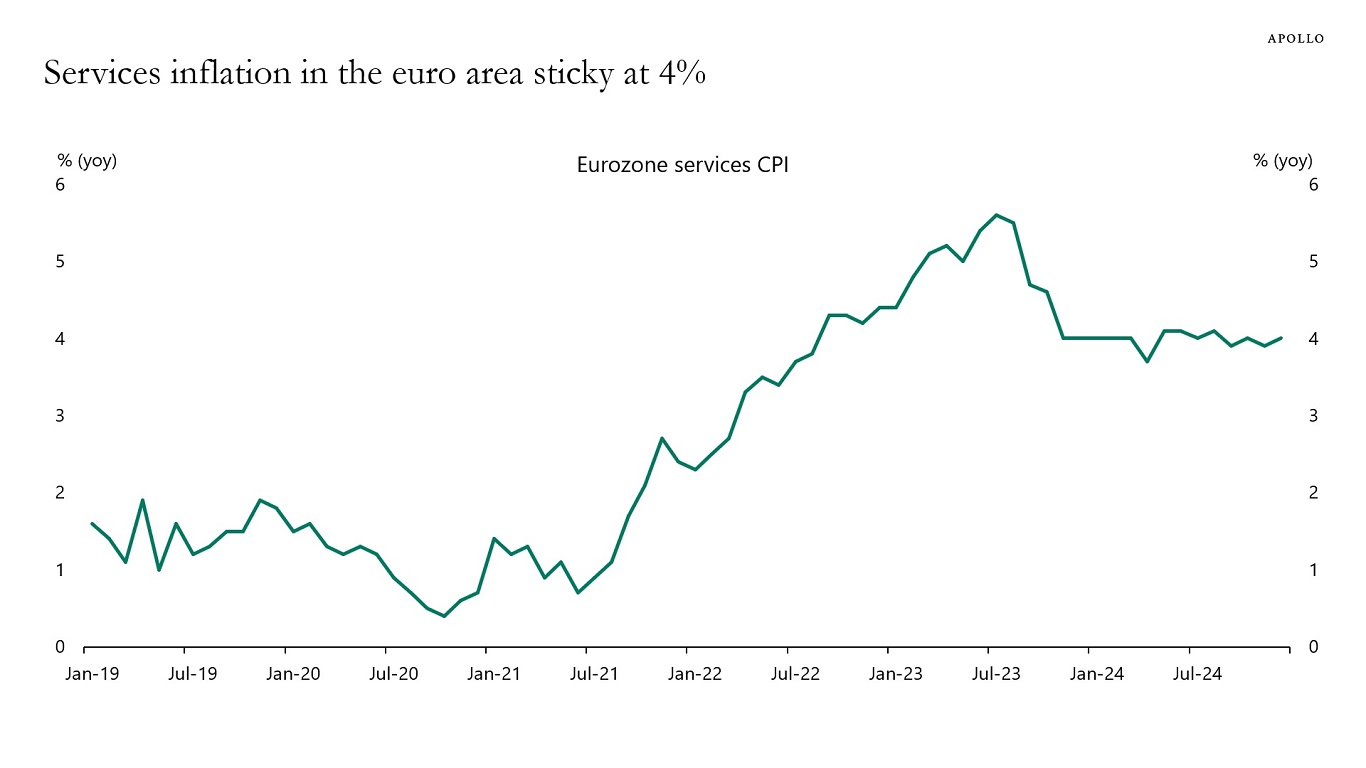

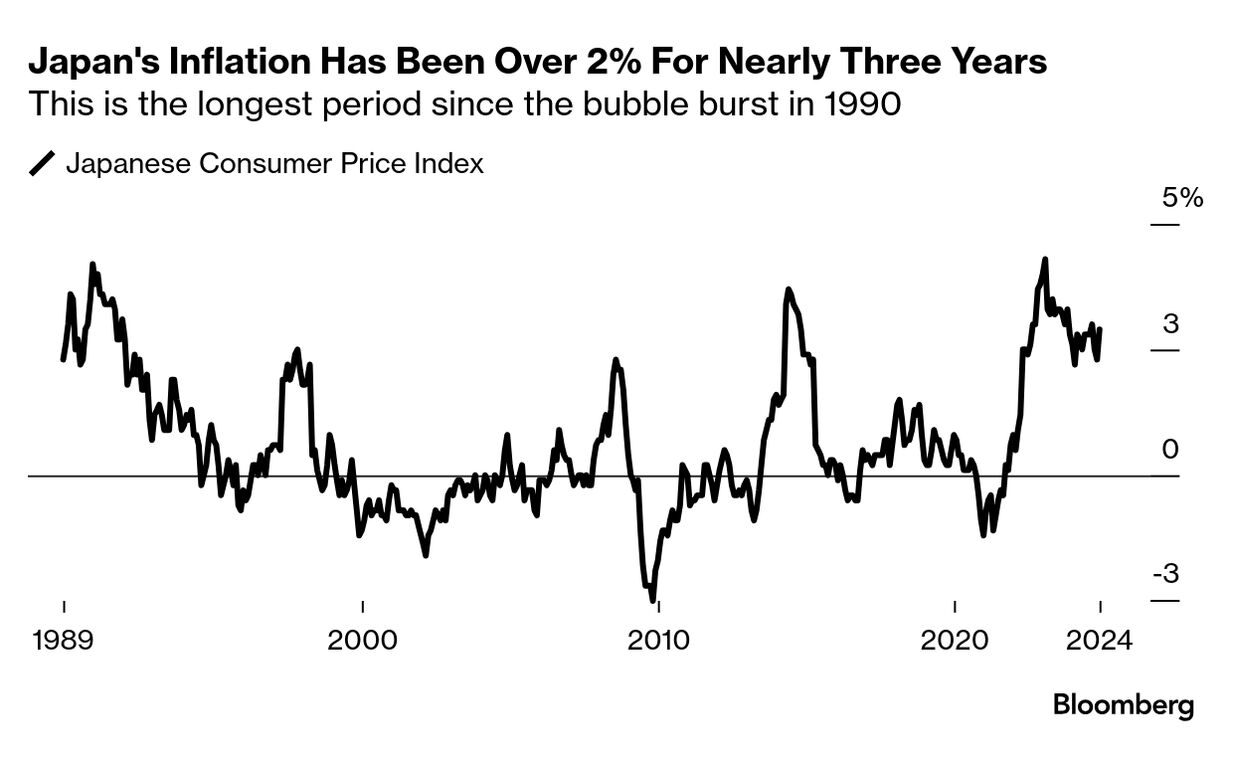

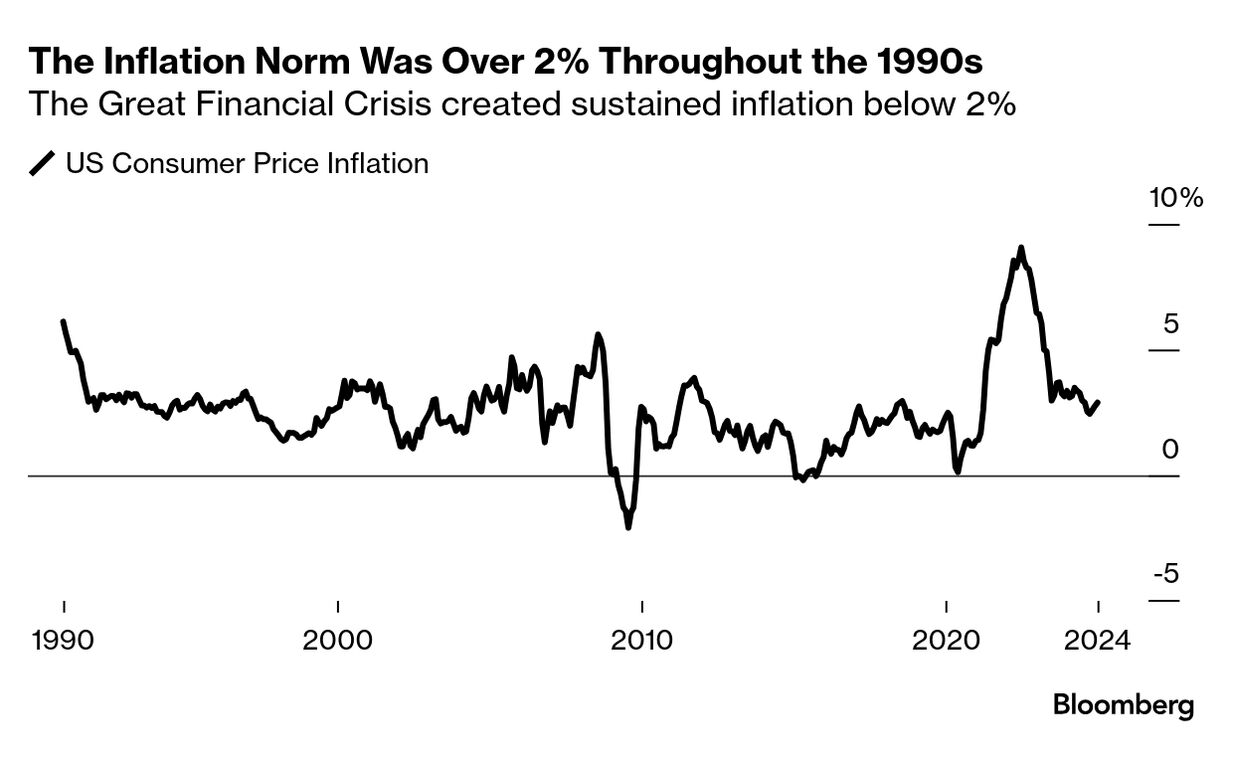

| 3% inflation isn't the end of the world. The best recent period of growth in the US, the 1990s, saw inflation consistently over 2% except during the Asian Financial Crisis and the LTCM collapse. Sustained inflation below 2% was an artifact of the balance sheet repair and low growth period after the Great Financial Crisis — something we don't want to re-visit. Perhaps then, we should just think of this post-pandemic new normal as a return to the pre-crisis norm of 2 ½% inflation and decent growth. The big difference is demographics | If I had to pick one thing that's different this time, it's the demographic component. In the 1990s, the world was welcoming in the post-Soviet bloc and Communist China labor supply into global trade, which helped lower consumer prices around the world. The US was also moving toward freer trade with places like Mexico, which both helped de-industrialize the States and reduce prices. Birth rates and anti-immigrant fervor had yet to shut down population growth in the industrialized west too. You take away these three components and what was 2 ½% inflation becomes 3% inflation pretty quickly. This puts the Fed in a bind. On the one hand, lowering interest rates to zero percent during the pandemic allowed the majority of high-income households and big businesses to lock in favorable fixed-rate debt terms that will last for years to come. That means high rates simply don't have as big of a punch as they usually do — and lowering rates may ironically actually lower growth if it has more of a negative impact on interest income than it does on relieving financial distress. On the other hand, the Fed simply hasn't created anywhere near the kind of financial distress that would slow the economy though monetary policy. And so, if Trump's pro-inflationary policies start kicking in, the next move by the Fed could very well be to hike rates, not lower them. And given how high rates have less impact because of the 'rate lock' situation, the central bank might even need to raise rates enough to cause a recession in order to get monetary policy to have any anti-inflationary impact at all. You can hear some Fed officials saying just the opposite. People like Chicago Fed President Goolsbee, New York Fed President Williams and Fed Governor Waller have all suggested rate cuts are still on the table as soon as March. The market is priced as if July is the next rate cut. Realistically, I don't expect even that. Here's why this is bad news | Normalization of macro variables back to the pre-GFC era also means normalization of asset price ratios too. When Jamie Dimon, the last remaining big bank CEO who served before the GFC, says "asset prices are kind of inflated", he's hearkening back to that pre-GFC time when bond yields were higher and price/earnings ratios were lower. If we normalize back the numbers that prevailed just 20 years ago, we're talking about a S&P 500 P/E ratio around 20 times instead of today's 25 to 30 times earnings. And when growth was good and inflation at 2.5% during the 1990s, the 10-year bond was at its nadir during a crisis at 4.15% — a level that helped fuel a bubble. Before the Asian Crisis, it was rarely below 6%. In a world of re-shoring, tariffs, and slower industrialized nation population growth, the bigger risk is higher inflation, higher yields and therefore lower P/E ratios. That's bad news for stock and bonds alike, though good news for savers. My expectation for 2025 is sustained inflation and, therefore, 10-year bond yields above above 4.50%, with any level above 4.75% having a negative impact on long duration assets like equities. Sustained yields above 5% are a decently-sized tail risk. So, for equities, while we are about to hit new record highs, I just think these levels won't last for the entire year. |

No comments:

Post a Comment