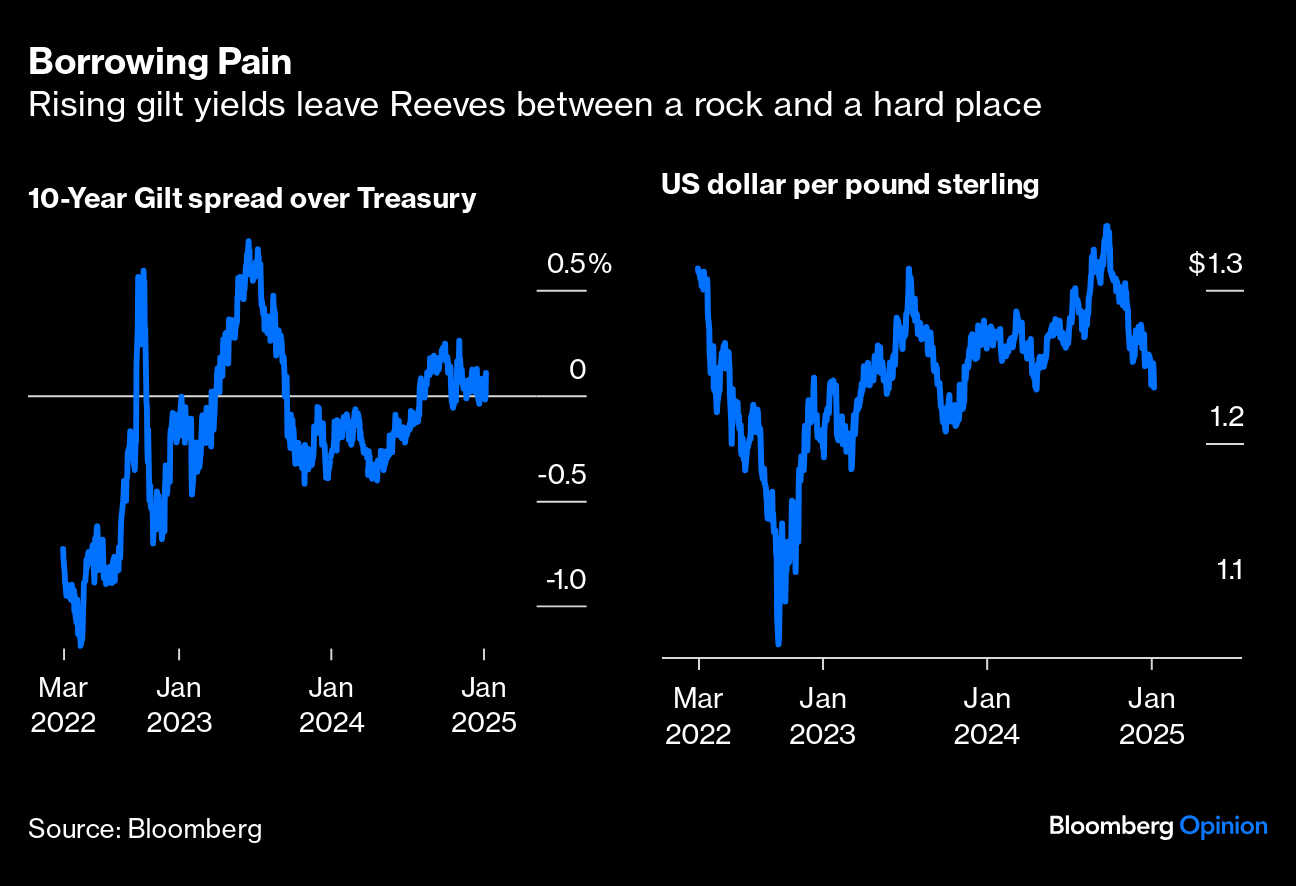

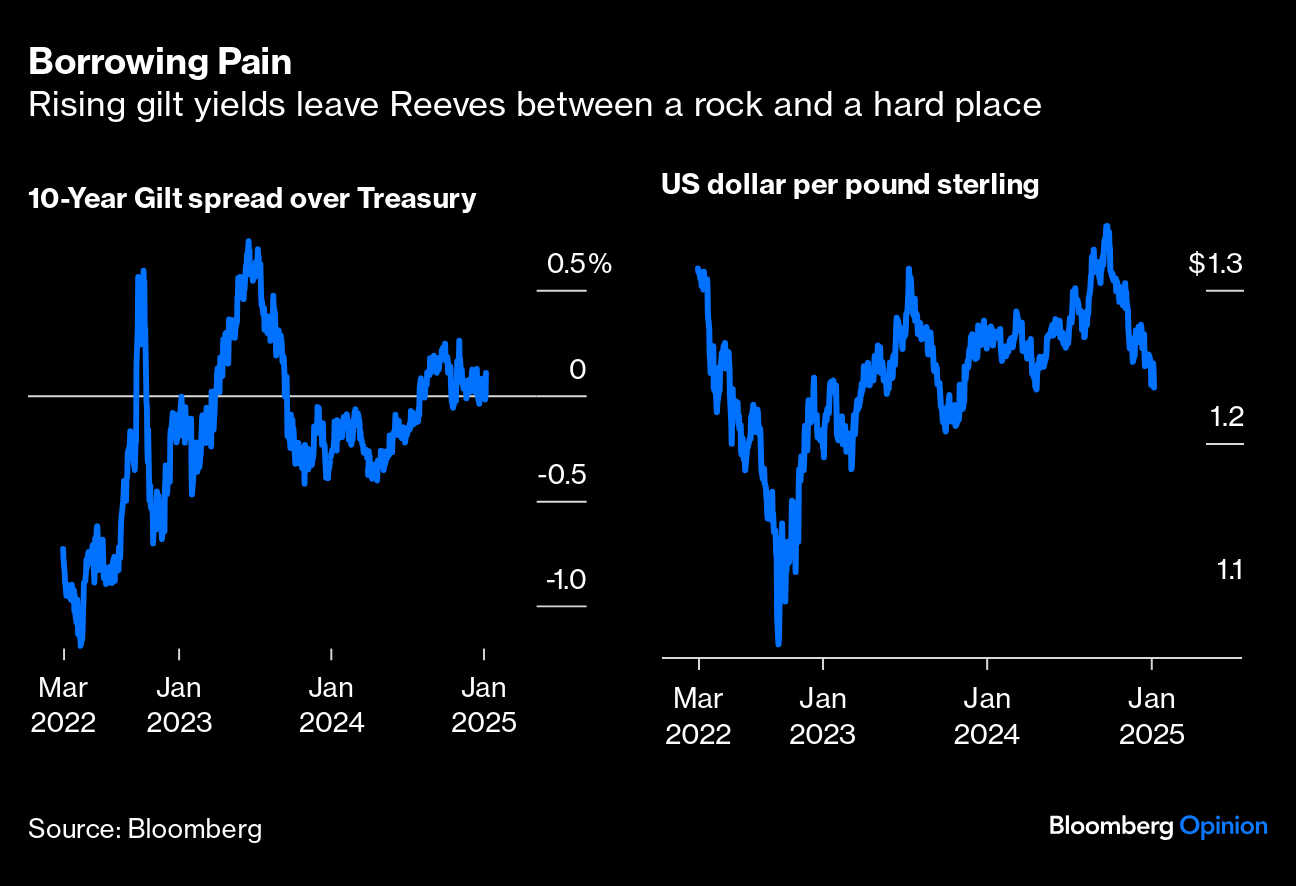

Gilts Near Fearful Truss Moments | The global bond selloff is unnerving for many reasons, but perhaps most because of the burden rising yields place on governments' fiscal operations. The pain inflicted by rapidly rising borrowing costs is hardest to mask for countries like the UK with razor-thin spending buffers. And so it really hurts that long-dated gilt yields spiked to the highest levels since the late 2000s — or, in the case of the 30-year gilt, since 1998. Capital Economics estimates that the recent move has added almost £9 billion ($11 billion) to the UKs borrowing costs — and that will virtually wipe out Chancellor Rachel Reeves' spending buffer of £9.9 billion. Plugging that gap will require tax hikes, spending cuts, or both. The scale of fiscal consolidation required will depend on how far the bond market's rout goes. The combination of rising gilt yields relative to Treasuries with a weakening pound is concerning. Still, the comparison with Liz Truss' self-inflicted 2022 gilt crisis is overblown:  Truss' ill-fated tax-cutting budget pushed the 10-year gilt spread over Treasuries to its highest in over a decade. To date, this mess is far less extreme, but needs urgent sorting. The UK's current and capital account deficit leave it vulnerable to foreign investors who might demand higher yields and a cheaper pound before they're prepared to buy gilts. The country is "dependent on foreigners," as one investment banker put it. The surge in the 30-year gilt back at levels not seen since before the financial crisis caused by the little-remembered Russian default of 1998 shows that the situation is serious: While Truss-style deficit spending may not be revisited, Reeves has an uncomfortable decision. Ahead of the UK's Office of Budget Responsibility forecast in March, Nico FitzRoy and David Pagliaro of Signum Global Advisors argue that the government could declare a breach of its own fiscal rules if the buffer evaporates further: In our view, further tax hikes remain unlikely in 1H this year, despite much commentary to the contrary, with spending controls instead more probable... The sizable tax hikes enacted in the recent budget are at least partly responsible for the recent worsening of business sentiment — the government will likely fear triggering a recession through another round of tax hikes so soon.

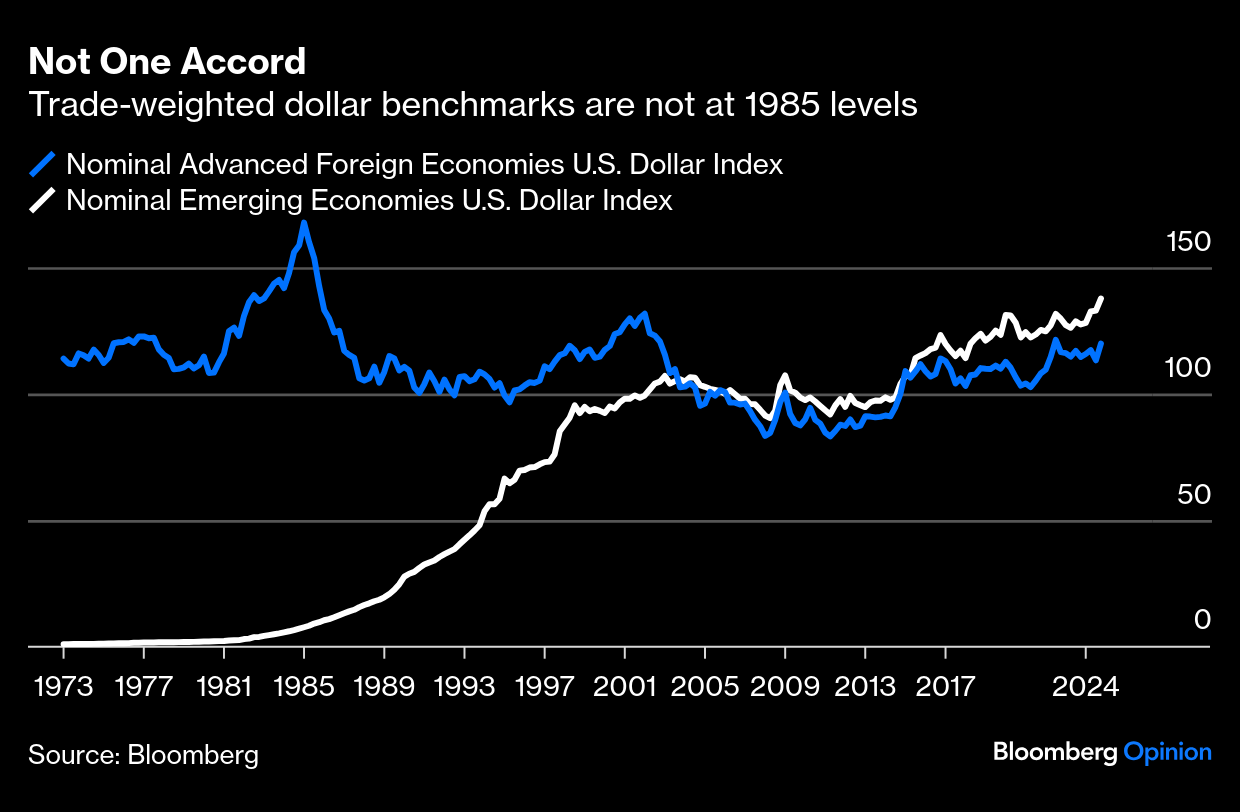

None of this is at all welcome for a new government that has had a rocky start. On the other side of the Atlantic, the rise in Treasury yields is as painful, but far from tragic. The 10-year benchmark yield is on a four-day rising streak — gliding past 4.7%, its most since April. Inescapable reasons for this surge include a change in fundamentals and the strong dollar. Joseph Lavorgna of SMBC Nikko Securities (and an adviser to Donald Trump in his first presidential term) attributes the currency's strength to the strong inflows to US financial markets generated by equity performance and expectations that Trump's pro-growth agenda can raise productivity. In trade-weighted terms, the greenback benefited from the US election and the recent repricing of the Fed's likely trajectory to gain 6.4% in the last quarter, according to Bank of America. With such dominance, there is speculation about whether a version of the 1985 Plaza Accord that devalued the dollar against its peers would be needed. Using the Fed's own measure, the dollar looks far less overextended now: Bannockburn Global FX's Marc Chandler argues that all else equal, the Fed's relative hawkishness in their December meeting will keep the world's reserve currency strong. While Trump's tariff agenda poses an inflation risk, Chandler argues that it will ultimately hurt far more in other countries, such as Canada and Mexico, which export 80% or more of their products to the US. That would mean a stronger dollar. The currency's strength could wane as and when we have clarity on Trump's trade policy, according to Bank of America's analysts. They expect the dollar to stay strong in the short term thanks to worries about inflation and particularly tariffs, but to weaken later in the year as these policies take a toll on the US economy the rest of the world responds. That would relieve pressure on the rest of the world, but is unlikely to come in time to relieve Rachel Reeves from some difficult decisions. —Richard Abbey Of Irrational Exuberance and Animal Spirits | When all else fails, and you cannot explain why markets are so high, John Maynard Keynes and Alan Greenspan have some concepts to help. You can blame "animal spirits" (Keynes) or "irrational exuberance (Greenspan). The question is whether they really explain anything. Greenspan gave us the concept of irrational exuberance in December 1996. Bill Clinton had just been reelected and stocks were motoring along. In a speech, Greenspan asked this question: How do we know when irrational exuberance has unduly escalated asset values, which then become subject to unexpected and prolonged contractions…? And how do we factor that assessment into monetary policy?

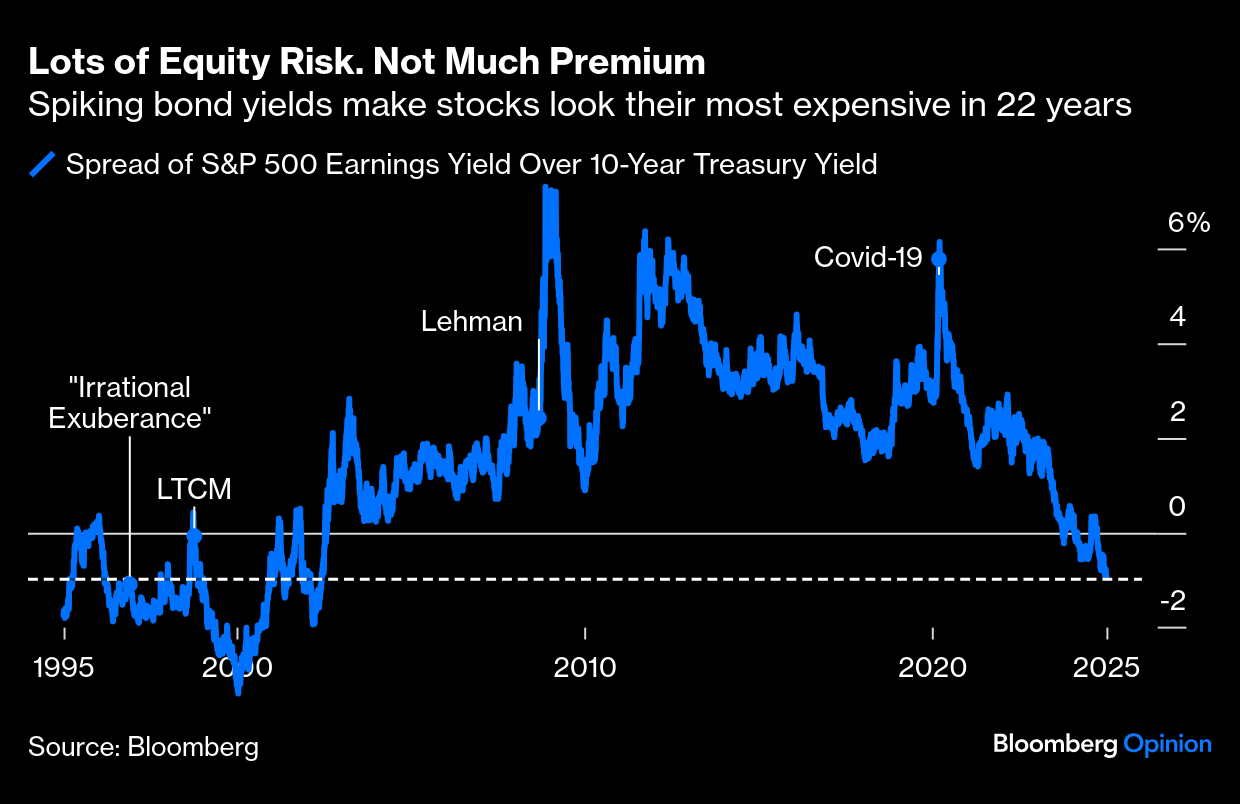

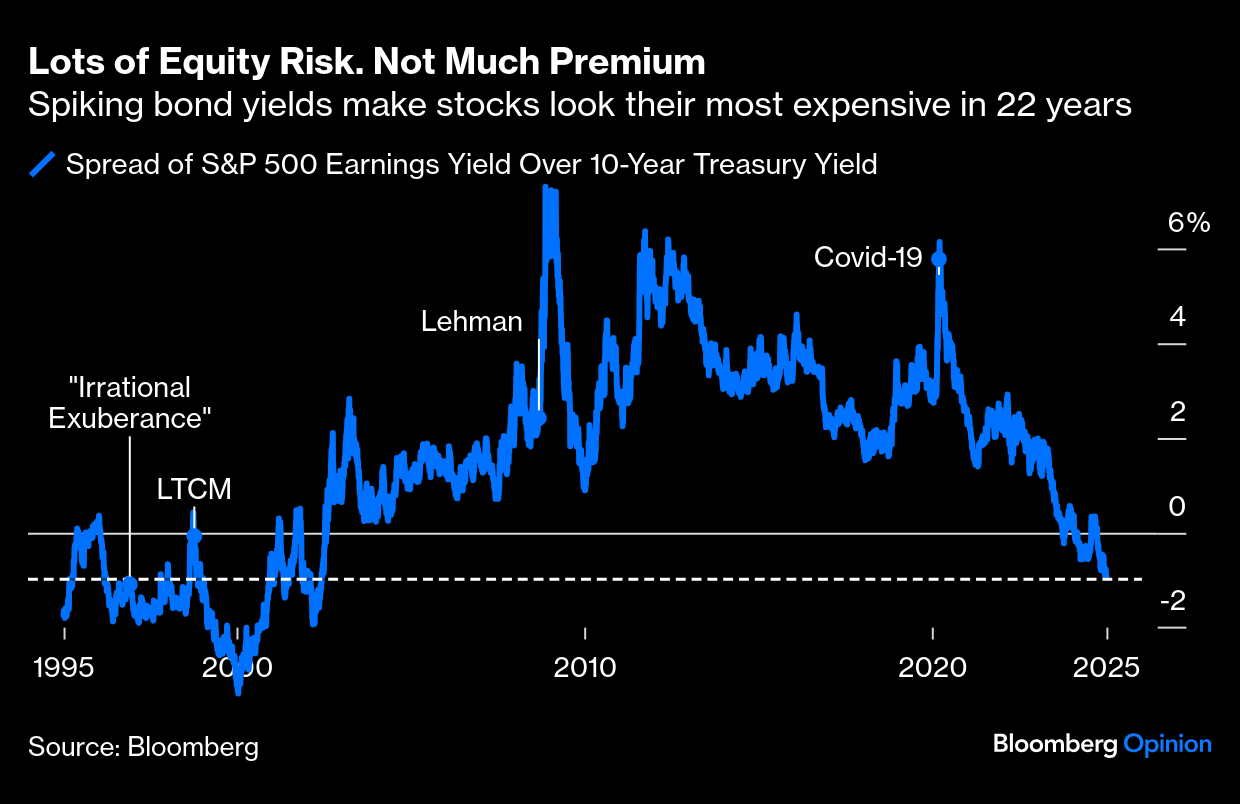

Markets took him to mean that he thought asset prices too high and was intending to do something about it. Stocks fell. Three months later, he followed up with a 25 basis-point hike, driving a correction in the S&P 500 of nearly 10%. But rates didn't move again for 18 months.  Greenspan tells Congress what he means in 1999. Photographer: Linda Spillers/Bloomberg To explain why he was worried, we can use another Greenspan concept, the Fed Model. Testifying to Congress, he often compared the earnings yield (inverse of price/earnings) for stocks with bond yields. The higher equity yields reached compared to bonds, the cheaper stocks were. And vice versa. High bond yields made stretched equity valuations harder to justify. We can illustrate this with the spread of the S&P earnings yield over the 10-year Treasury. When it drops, or falls below zero, stocks are expensive. This simple model (there are more sophisticated versions, but this captures Greenspan's concept) showed that stocks were way too expensive:  For current purposes, this measure now says that stocks are their most expensive since 2002 — and coincidentally at exactly the level on Dec. 5, 1996, that prompted Greenspan to sound his warning. So concerns about irrational exuberance seem justified. There is also something of a morality tale in what happened in the autumn of 1998. Following the Russian default and the meltdown of the Long-Term Capital Management hedge fund, the spread went positive again — stocks yielded slightly more than bonds. But the corporate credit market was becalmed, and Greenspan decided to cut the fed funds rate between meetings, launching the most extreme phase of the dot-com boom. We cannot know what would have happened if the Fed had held its nerve after LTCM, but with hindsight it looks like a mistake. Some six decades before Greenspan, Keynes offered the concept of animal spirits in his General Theory. This is how he introduced it: A large proportion of our positive activities depend on spontaneous optimism rather than on a mathematical expectation… Most, probably, of our decisions to do something positive, can only be taken as a result of animal spirits — of a spontaneous urge to action rather than inaction, and not as the outcome of a weighted average of quantitative benefits multiplied by quantitative probabilities.

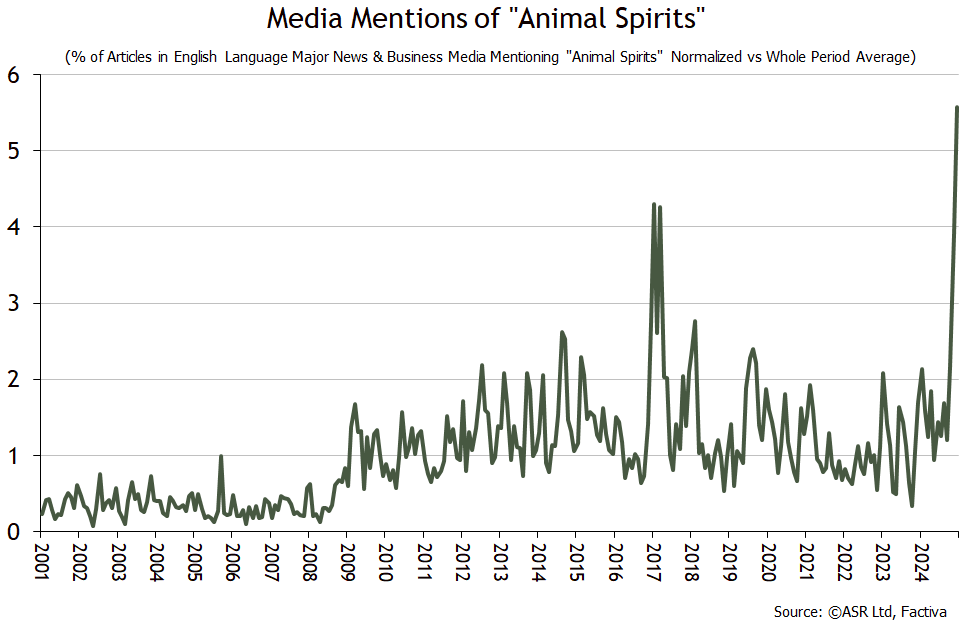

Most of the time, Keynes' cost-benefit analysis will satisfactorily explain asset price moves, but sometimes it won't. When we can't understand what's going on, we tend to cite "animal spirits" as a get-out clause. Use of the term might therefore offer a guide to when valuations have become inexplicable (or, as Greenspan would have it, irrationally exuberant). Ian Harnett of Absolute Strategy Research tried using it this way, and produced the following search of English language articles on the Factiva database. It goes back to 2001, and shows that invocations of animal spirits ended last year at an extreme: If there are animal spirits at work, Harnett warns, "then investors might want to be wary of what kind of 'spirits' they really are!" In his experience, "they tend to be capricious little things with a nasty bite." Personally, I think that this is a pretty incredible/scary chart. To my mind, "animal spirits" tend to be what people rely on to explain things when markets are completely out of whack with underlying fundamentals and valuations can no longer be justified, but people still expect markets to go higher!

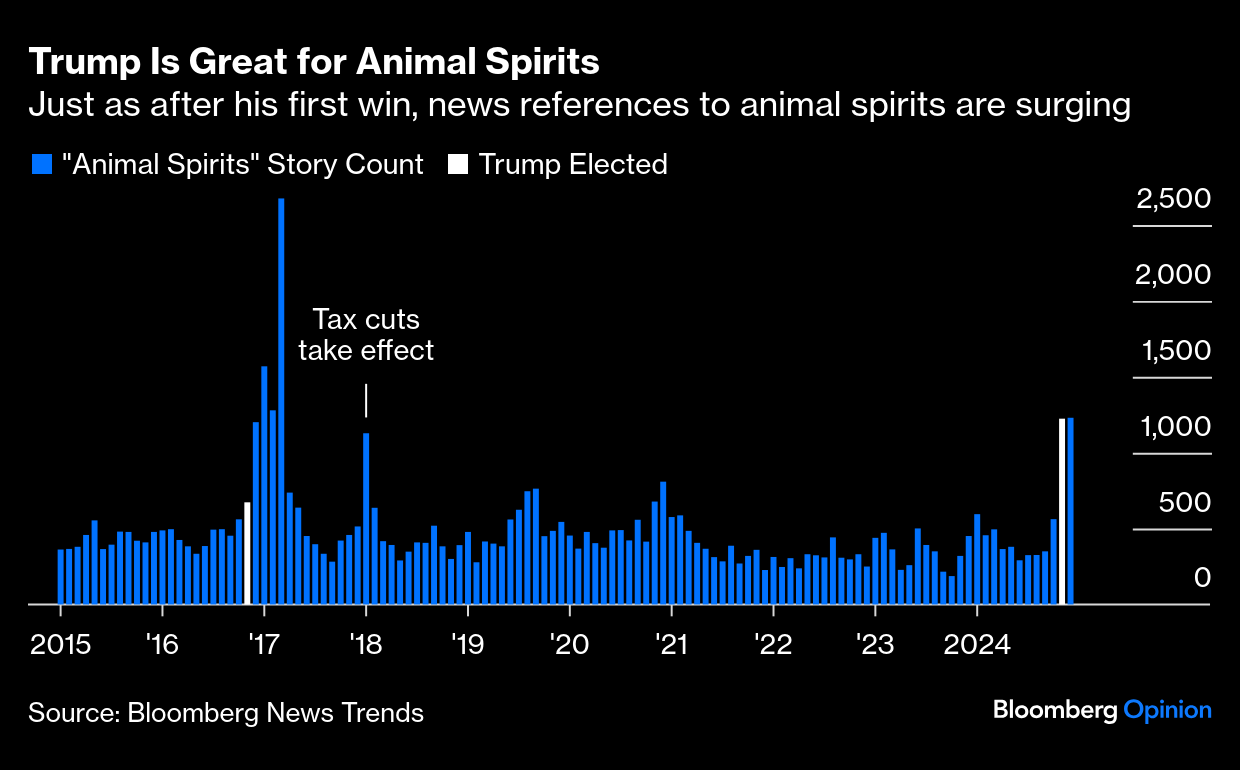

I delved further into this with a Bloomberg News Trends search, which counted all references to animal spirits in stories published on the Bloomberg terminal from all sources. This goes back to only 2015, but might have the advantage of being drawn more exclusively from stories aimed at people in finance. Using this version confirms a surge in excitement about animal spirits, but suggests they were causing even more excitement in early 2017, when Trump was taking office the first time: There was a second surge in the term in January 2018 when the Trump tax cuts went into effect, much against widespread expectation. Their passage had looked unlikely until late in 2017, so this was a positive surprise. Harnett's Factiva chart also shows a rise in animal spirits after Trump's first election. Where does this leave us? It's hard to explain current asset prices without invoking a woolly concept like animal spirits. Trump is the best explanation for their resurgence. Stocks are riding on potent optimism that Trump 2.0 will be good for the market. Should he disappoint in the months ahead, the exuberance will fade, and we would be left with a stock market that looks way too expensive. Many of you seem to be in need of some cacophony. To drown out the ever more irritating background noise of the moment, try listening to these, at loud volume: In My Time of Dying by Jimmy Page and the Black Crowes, REM's Finest Worksong, Motorbreath by Metallica, Stiff Little Fingers' Alternative Ulster, The Cranberries' Zombie, Fools Gold by the Stone Roses (in an extraordinary live performance), and In a Big Country by Big Country. By The Clash, try I'm So Bored with the USA, Brand New Cadillac, or Police on My Back. Then there are Jeff Beck's Bolero, Midnight Oil's Best of Both Worlds, Iron Maiden's Number of the Beast (frequently linked here because it comes in useful when referring to the S&P's low of 666 after the Global Financial Crisis), or The Jam's Going Underground. Are there any more out there?

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN . Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment