| Amid Trump 2.0's first week, it was easy to lose sight of a Trumpian shift that has been underway for a while, thanks to the intersection of Red State politicians and the US courts. ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance) investing was already under attack. Now, it might become illegal. Matt Levine has recently covered an attempt by a group of attorneys general to argue that index investing is illegitimate on antitrust grounds. Tennessee's attorney general declared ESG investing dead after announcing a settlement with BlackRock over allegations that it was concealing the ESG principles in its corporate stewardship from its investors. BlackRock must now beef up its proxy-voting disclosures. Then a Texas court ruled that American Airlines had been disloyal to the company's employees who pay into the company's 401(k) plan by failing to stop BlackRock's ESG-driven approach to proxy voting. The judge, Reed O'Connor, is popular with conservative activists. His argument delves into the questions of whether ESG investors are trying to achieve environmental ends (not acceptable), or hoping that green criteria will help maximize returns (which would be OK). ESG marketing often blurs these issues, and O'Connor decided that BlackRock is on the wrong side of the line. It's a fascinating and difficult debate. For now, let's focus on two factual claims in O'Connor's opinion. First, there is this line: By focusing on non-pecuniary interests, ESG investments often underperform traditional investments by approximately 10%. For instance, when compared to the S&P 500 and the Russell 1000 indices in 2023, ESG funds dramatically underperformed non-ESG funds, with ESG-related funds returning about 8% compared to about 14% for both indices.

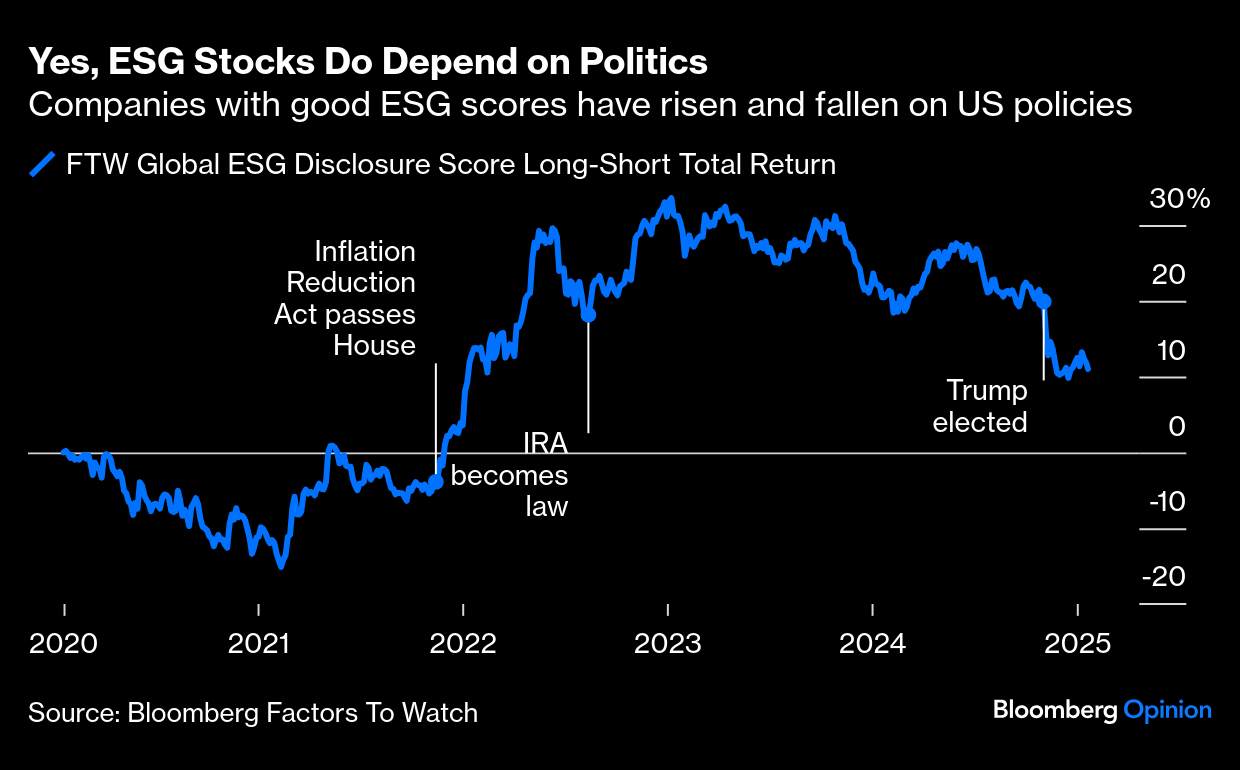

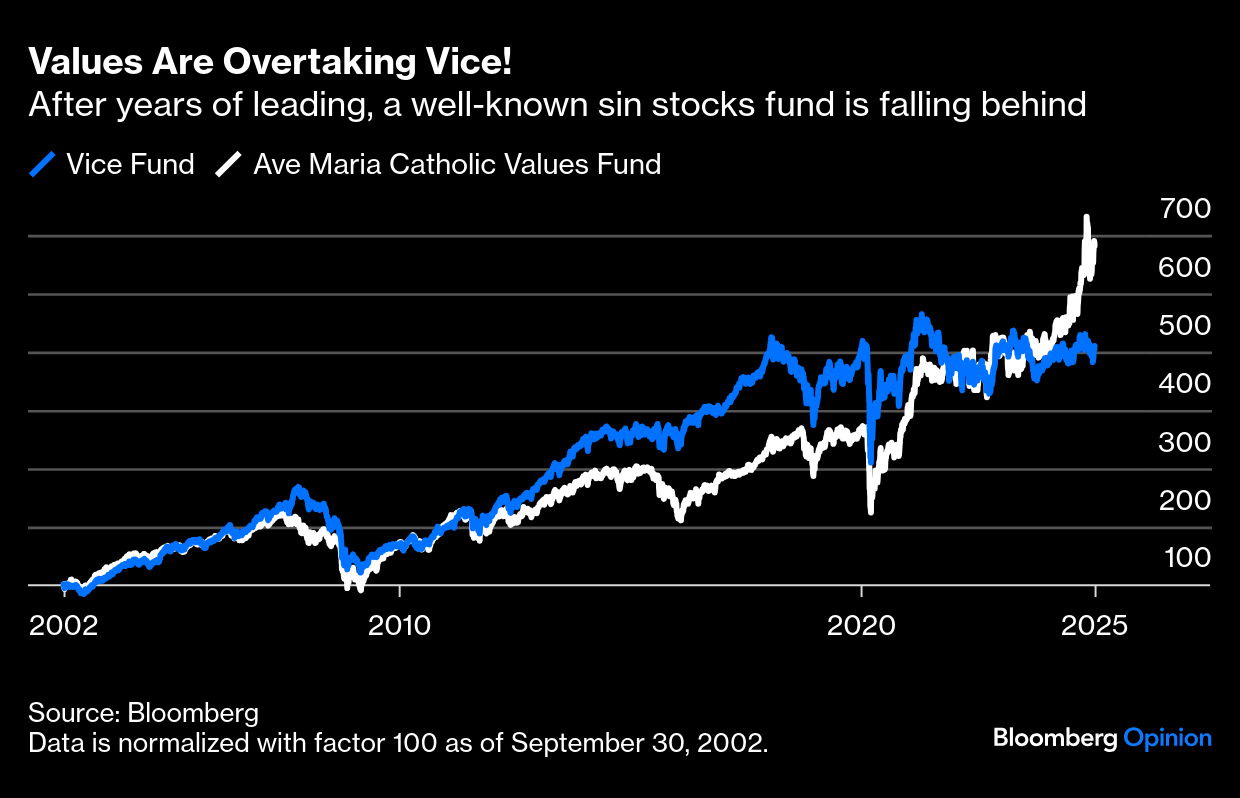

The judge gives no indication of where he got this information. There are umpteen ESG indexes, and many definitions of ESG. After half an hour on the Bloomberg terminal, I couldn't replicate these numbers, but I assume it's possible. For a scientific approach, Bloomberg's Factors To Watch monitors ESG as a factor analogous to growth or value. Globally, this is how the 20% of stocks with the best ESG disclosure scores have performed compared to the 20% with the worst. It suggests that A) government policy really drives this, and B) no, preferring stocks with good ESG scores doesn't lose you 10% per year: Alternatively, S&P offers a version of the S&P 500 which overweights the stocks with the best ESG scores, and then reshuffles to mimic the S&P 500. Thus trustees under pressure from the environmentalist left rather than the anti-ESG right can say they've done their bit for climate change without costing their clients; the financial engineering lets them have their cake and eat it. Since inception in 2005, this strategy has worked: Avoiding sinful stocks is not new. Over history, it's had the counterintuitive effect of making sin stocks cheaper for those with fewer scruples and improving their returns. According to Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton, alcohol was the UK's best performing sector of the 20th century, while tobacco took the title in the US. Sin is a human constant and makes money in the long run. That suggests ESG indeed harms investors' returns. But the ESG backlash has produced a historical anomaly. This is how the Vice Fund, which invests in tobacco, alcohol, gambling and arms, has fared versus the Ave Maria Catholic Values Fund, which puts Christian precepts ahead of maximizing profits. Suddenly, vice stocks are in eclipse: O'Connor's other central contention is that BlackRock supported an environmentalist campaign against ExxonMobil, led by the Engine No. 1 group, which nominated dissident directors at a shareholder meeting held in May 2021. This is from the judgment: Three of Engine No. 1's dissident-director nominees were ultimately elected to Exxon's board. According to Exxon's Form 8K for June 2021, none of the three would have been elected without BlackRock's proxy votes. In response to this election, Exxon's stock prices, along with other energy stocks, fell.

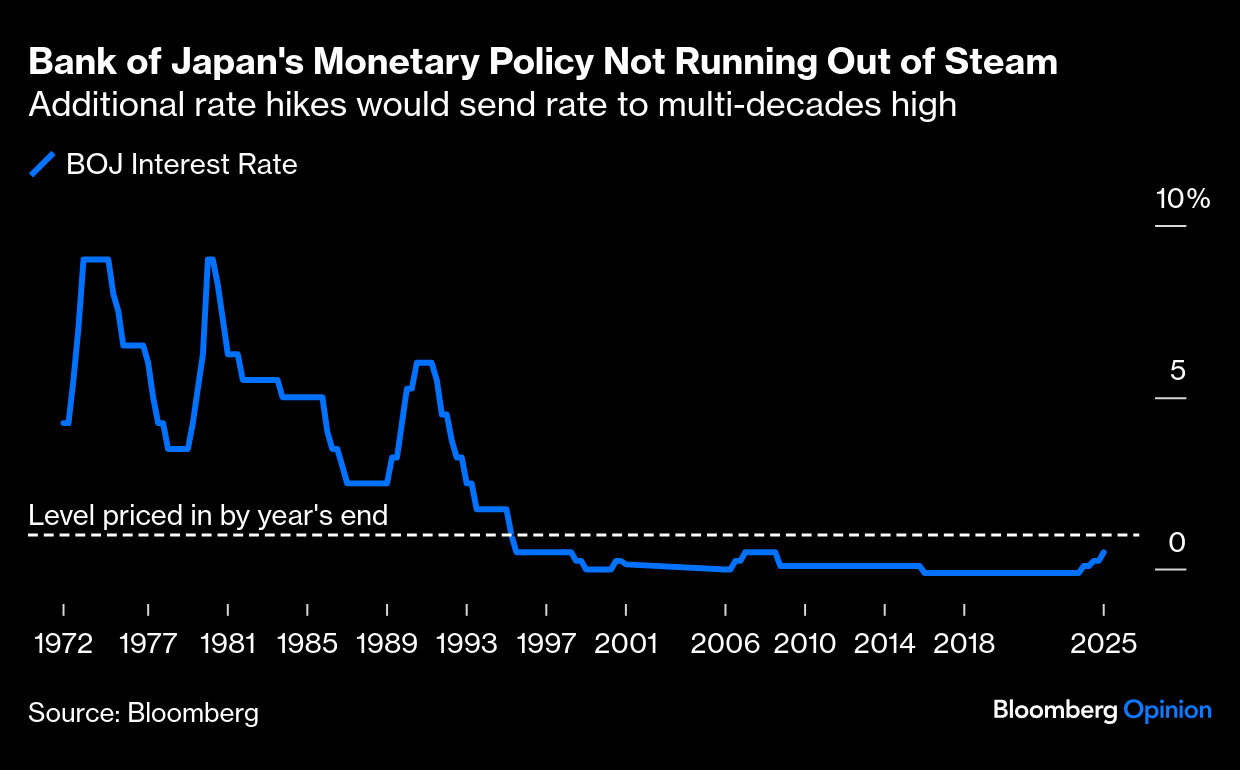

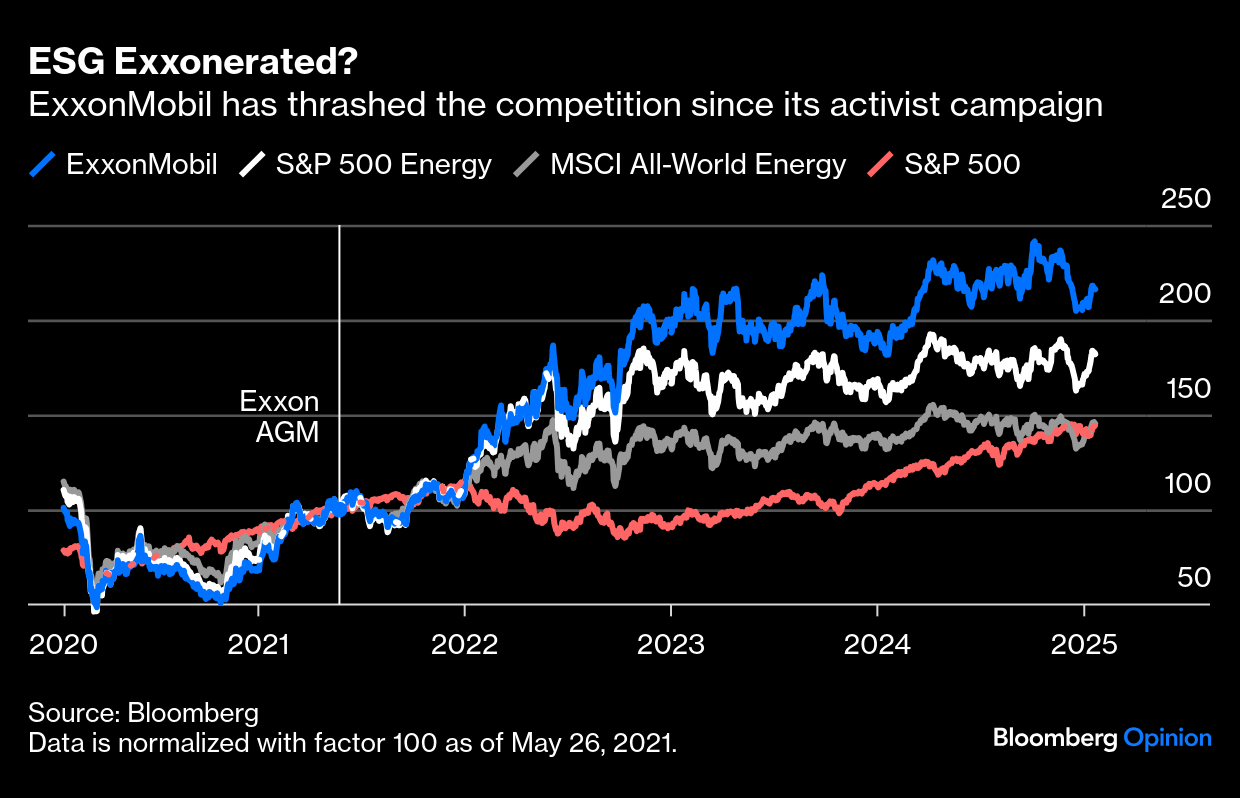

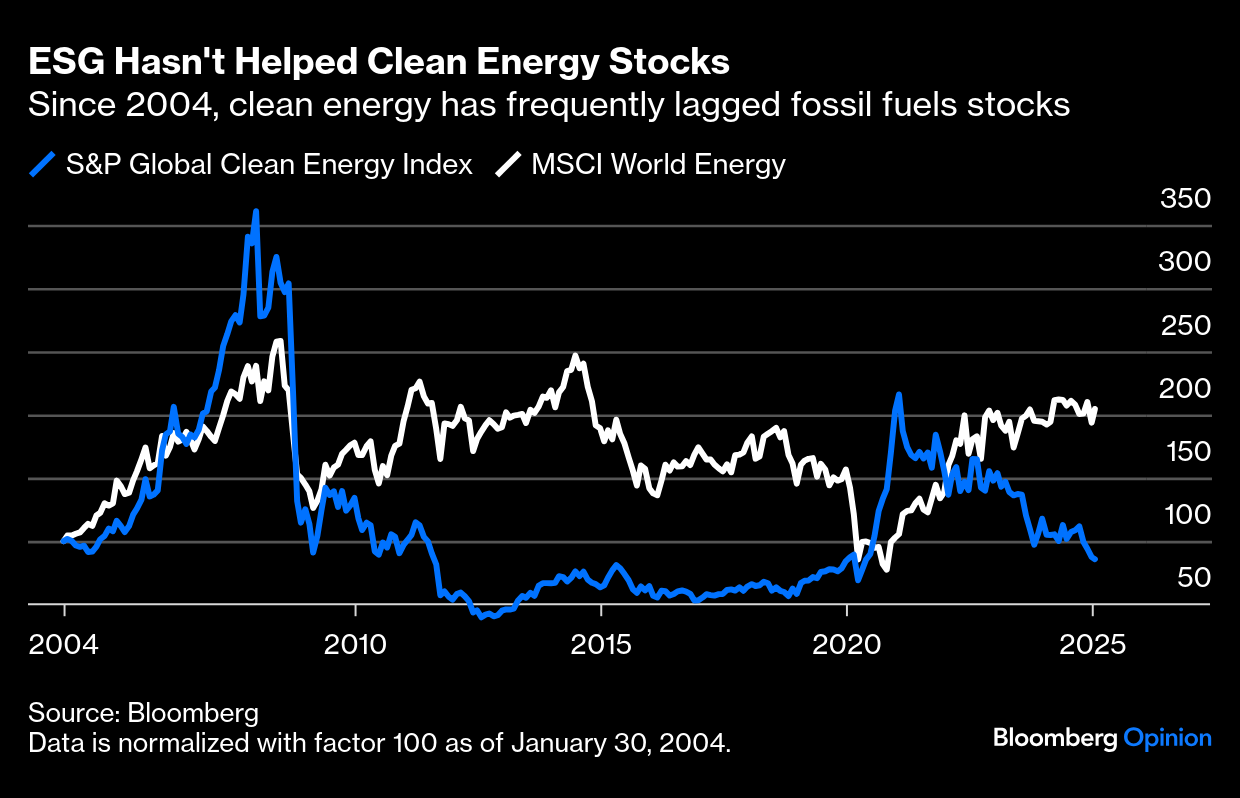

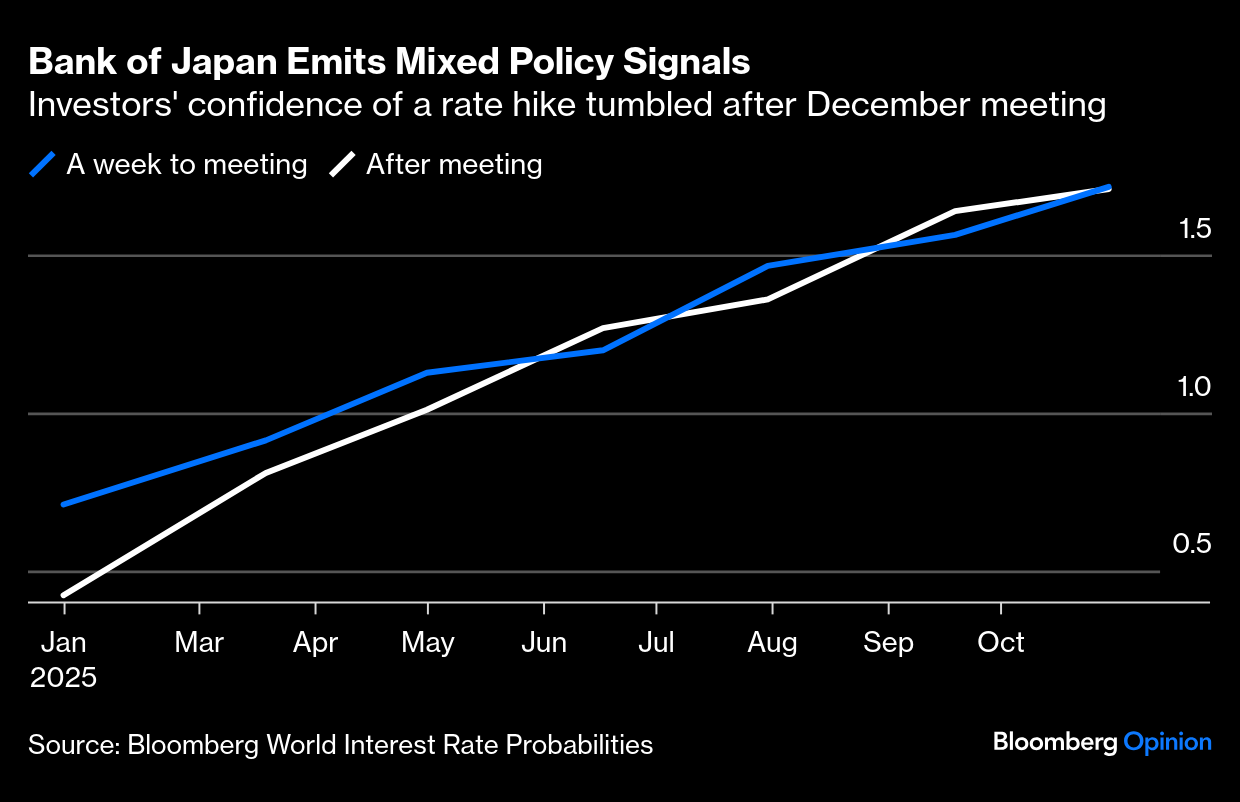

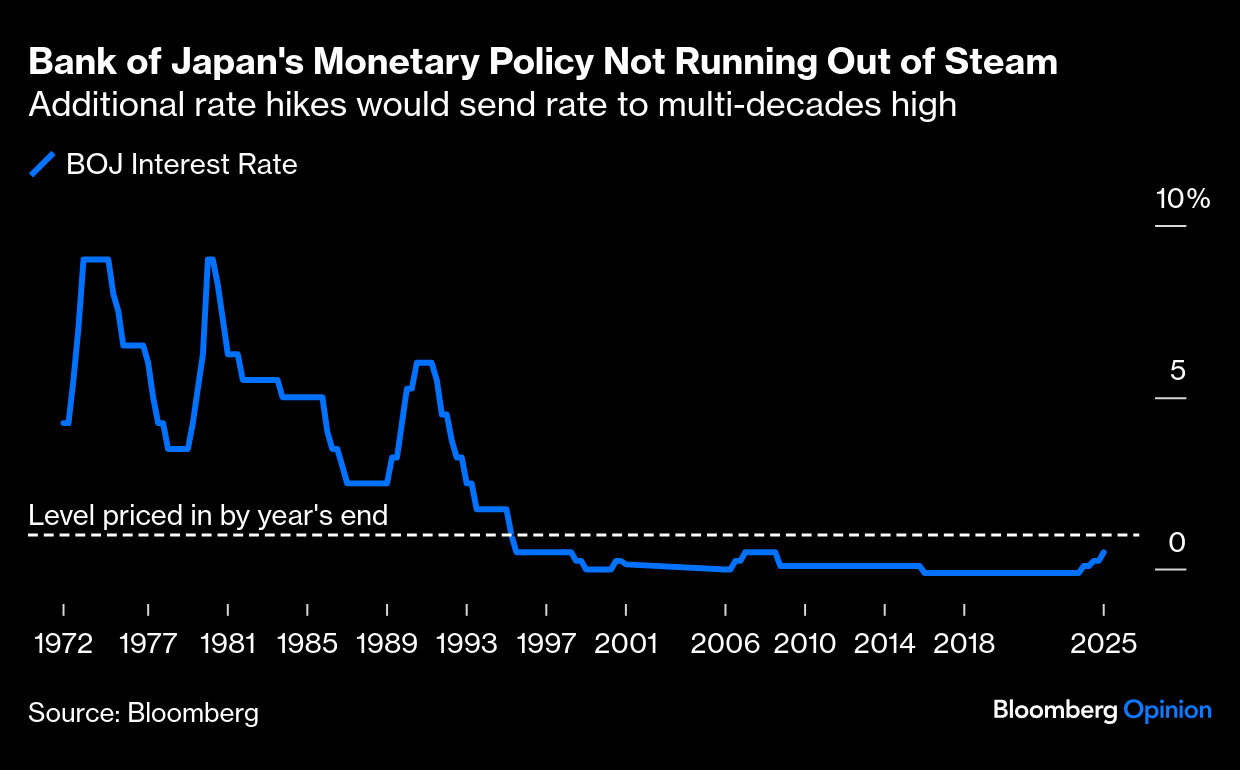

That seems straightforward. BlackRock forced Exxon to inflict economic damage on itself, and by extension its shareholders. The problem is that this is obviously untrue. Getting a company to hedge by diversifying away from its traditional products could avert disaster; think of Kodak. And it hasn't hurt Exxon. This is how the company performed compared to US and global energy stocks as a whole, and to the S&P 500. It's clobbered the competition since BlackRock foisted those directors on it: In longer perspective, Exxon's performance relative to the MSCI World energy index since 2000 shows that the activist campaign simply didn't harm its stock. It looks like evidence that you can indeed do well by doing good: Further, there's no evidence that ESG has diverted money away from fossil fuels. Since 2004, when the United Nations launched the ESG concept, this is how global clean energy stocks have fared compared with conventional energy stocks. There were spikes during perceived energy crises in 2008 and 2020. Other than that, clean energy stocks have lagged terribly: This suggests ESG isn't delivering for investors — although good contrarian pension managers might think this a good time to hoover up alternative energy stocks on the cheap. It also shows that after 20 years, it hasn't harmed the fossil fuel industry in the slightest. Indeed, the most important issue for ESG, and its opponents, is that it seems to have had little effect on anything. The world is still getting warmer, and voters still hate capitalism. Backers have to explain how their strategy has had so little impact on stocks and on the real world. The story is not that it's warped markets and the economy, but that it's been utterly ineffectual. As for the legal and political attempts to close it down, at present they're fighting against harms that are merely imaginary. Governmental and legal over-prescriptiveness could make capitalism work even less well than it does already. There are many ways an investor might try to beat the market, and the shareholder campaign at Exxon seems to have been one of them. If it's really now possible for a judge to rule that they shouldn't have done it, even when it made money for their clients, capitalism is in trouble indeed.  | | | For a central bank that had gone decades without tightening, the Bank of Japan's three hikes in a year, on the face of it, seem inconceivable. These are not normal times. Governor Kazuo Ueda's first hike took the country out of negative interest rates, while the second, in July, led to the spectacular collapse of the carry trade — where investors borrow in Japan's currency to park in high-interest assets — and briefly threatened global stability as money surged back to Japan. So it's impressive that the third hike has been greeted as "routine," even though it sent rates to a level not seen in nearly two decades. The central bank's latest quarter-percentage-point hike is further testament to its growing belief that it's on course to end the debilitating effects of deflation and stagnation. After mixed signals last month, the odds on a cut fell to less than 50%, according to the Bloomberg World Interest Rates Probabilities function, which gauges the implicit forecast for rates based on pricing in futures and overnight index swaps markets: As Ueda's team debated the timing of the next hike, investors shifted to expect an increase in March, not January. Ueda's bland messaging was partly to blame, leaning heavily on data dependency, while events elsewhere, especially the policy uncertainty surrounding Trump 2.0, added to investors' nervousness. The critical news since then: Wage negotiations, central to the bank's 2% inflation target, are going as planned. This suggests the notion that prices can go up is now entrenched in wage negotiations, something not true of any of the previous false alarms when Japan appeared to be awakening over the years. The hike gave the yen a respite, after relapsing into weakness: Where does the BOJ go from here? The market expects more hikes, although the magnitude and timing are unclear, and Bloomberg Economics' Taro Kimura believes the BOJ's guidance was aimed at heading off renewed yen strength: In his commentary, we detected subtle signs that start to build a case for the next hike. We maintain our baseline scenario that the BOJ will deliver two more quarter-point increases this year — in April and July — taking its target rate up to 1.0%, the lower end of estimates of Japan's neutral rate.

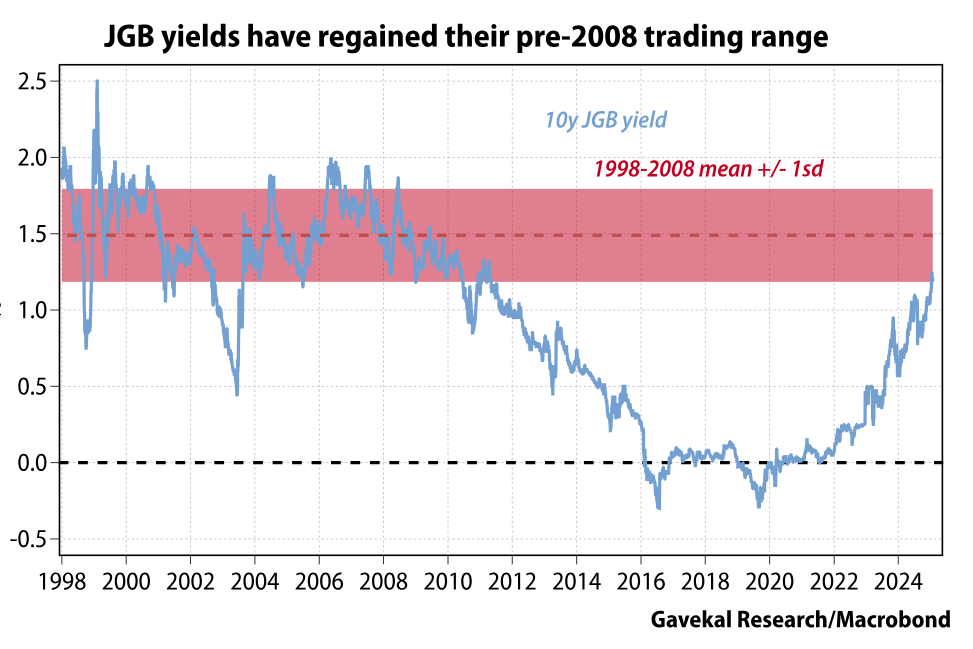

Such policy signaling hasn't always been apparent, as shown by the July surprise that led to the carry trade unwind. Before this month's meeting, Deputy Governor Ryozo Himino's subtle hints of an imminent hike a week earlier guided market expectations. Whether such guidance will be a thing going forward is hard to tell, but investors now seem confident that rates will soon be their highest since 1994:  Policy signaling isn't sacrosanct, especially with material external factors at play. Gavekal Research's Udith Sikand argues against BOJ bullishness. He sees little evidence that wage gains translate into more consumption, while household spending in real terms declined almost every month last year. Trump tariffs might have an impact. Sikand adds that Japan's $70 billion trade surplus with the US and the yen's undervaluation makes it an easy trade war target. When the BOJ says it wants to "conduct monetary policy so that the zero lower bound would not be reached," he argues that "the BOJ wants to raise rates now so that it has ammunition to expend during the next downturn." Sikand argues this could cause investors to revise upward their inflation expectations, short rates and term premiums — the three building blocks of long-term bond yields. This Gavekal chart shows the 10-year Japanese government bond yield has regained its pre-2008 trading range: With the 40-year JGB yield recently hitting a record 2.8%, Sikand suggests the BOJ could fuel another deluge of repatriation flows, much like those that triggered last summer's bout of global volatility. People the world over have gotten used to cheap money and liquidity from Japan. Removing it now, when the US is trying to change many other long-lived assumptions, carries risks. —Richard Abbey A Netflix recommendation. The brilliant Danish political drama Borgen (think "The West Wing Meets the Girl With the Dragon Tattoo") has done it again. Back in 2010, the creators told of how Birgitte Nyborg, the heroine, became Denmark's first female prime minister. The country elected its first woman PM shortly afterward. In 2022, they returned with Borgen: Power & Glory, in which Birgitte, as foreign secretary, deals with a crisis as Greenland brings Denmark into conflict with the US and China. Not only weirdly prophetic, it's brilliant viewing. Have a great week everyone. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: - Daniel Moss: Japan's Central Bank Drops the Drama and Wins on Rates

- Esha Dey: Wall Street's Big Hope Is Trump Pulls His Punches on Immigration

- Justin Fox: Los Angeles May Rise From the Ashes But Won't Be Transformed

Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN . Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment