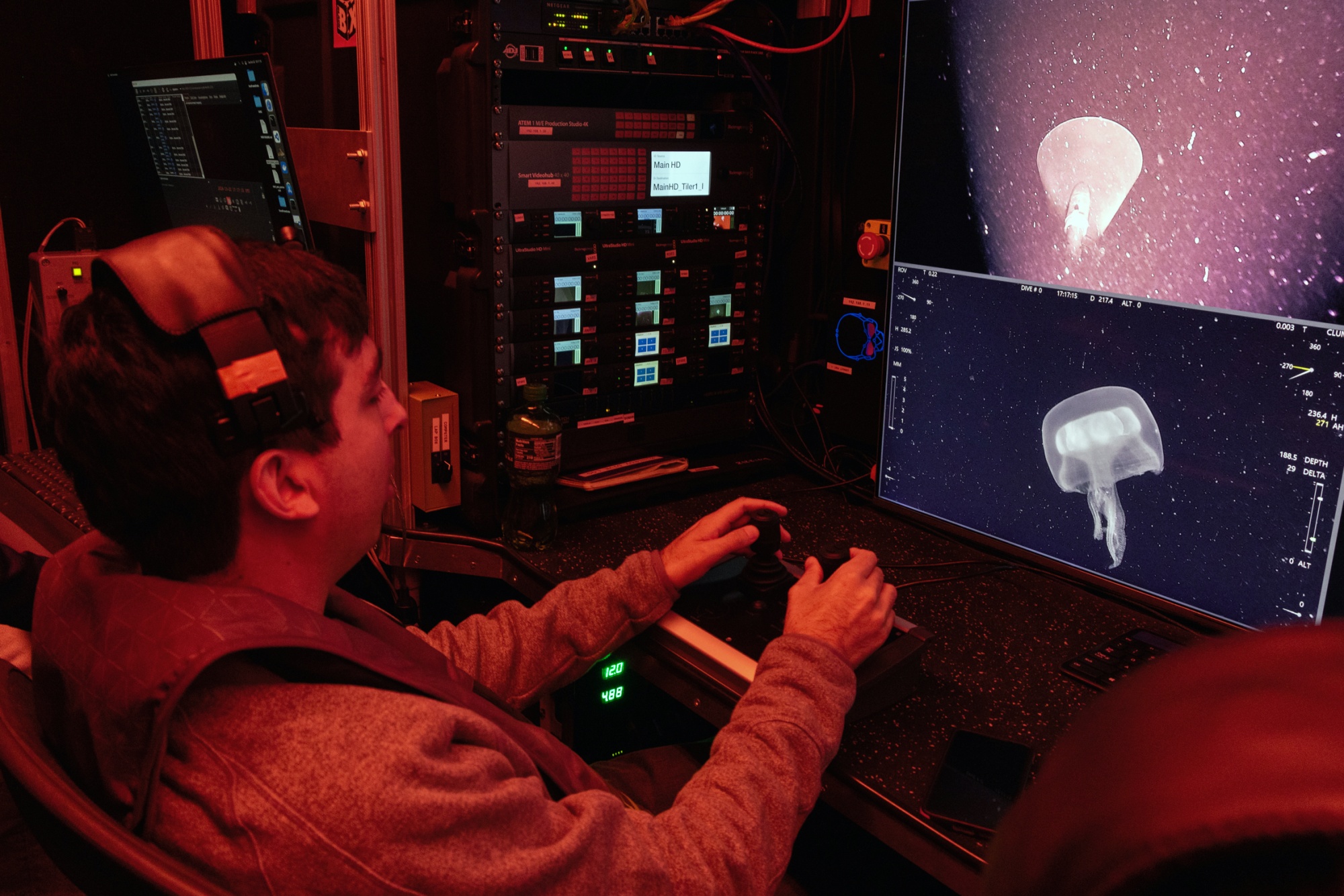

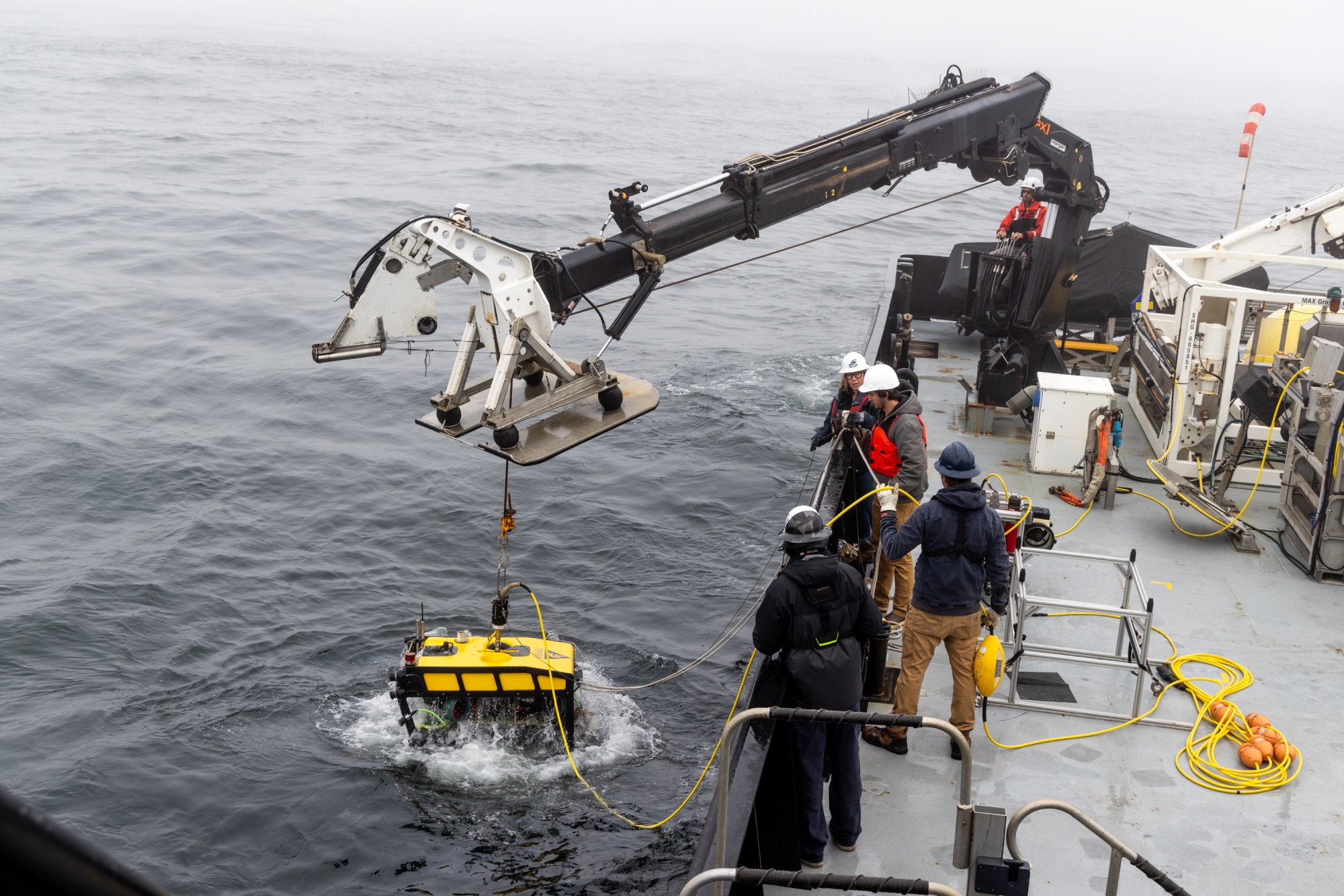

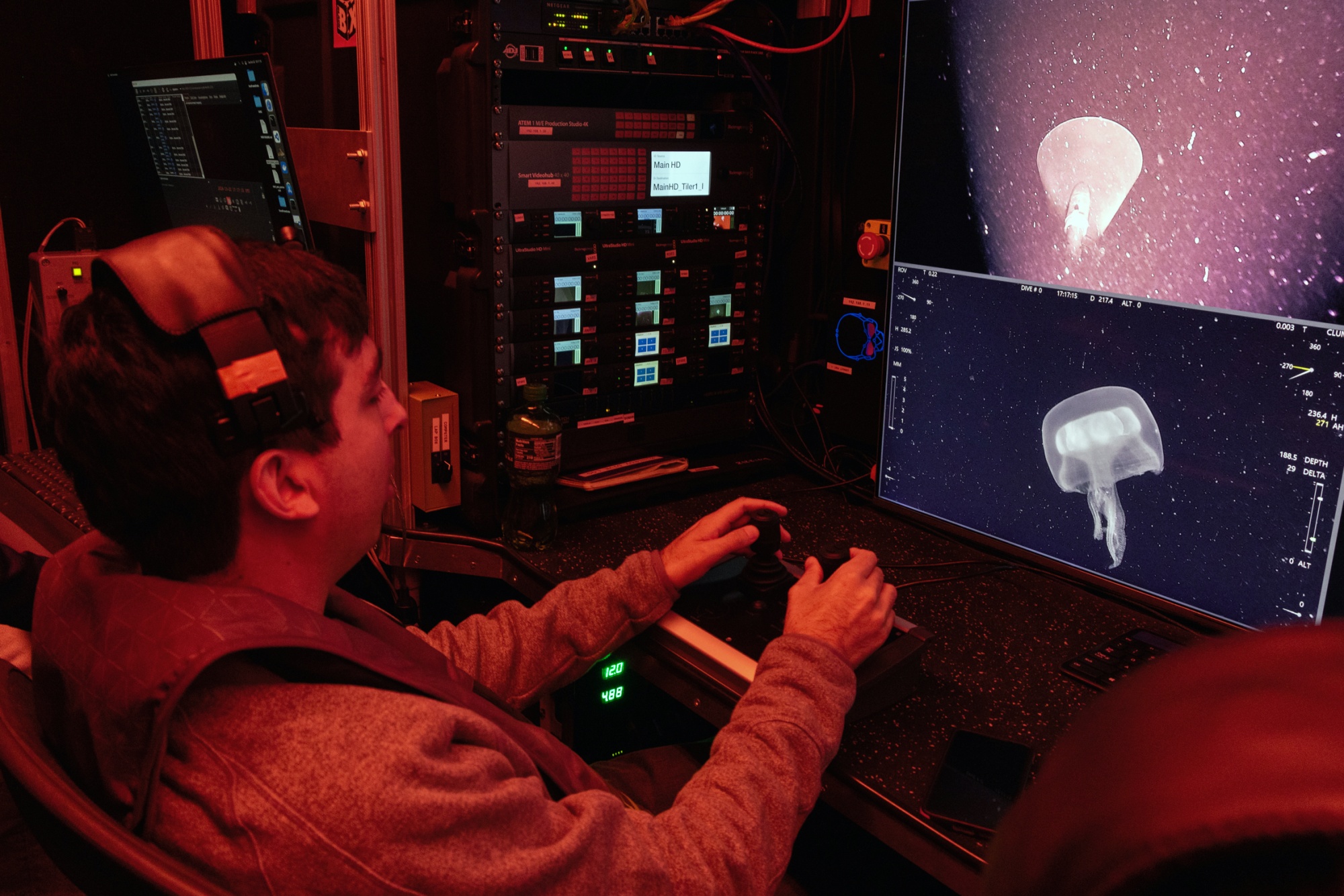

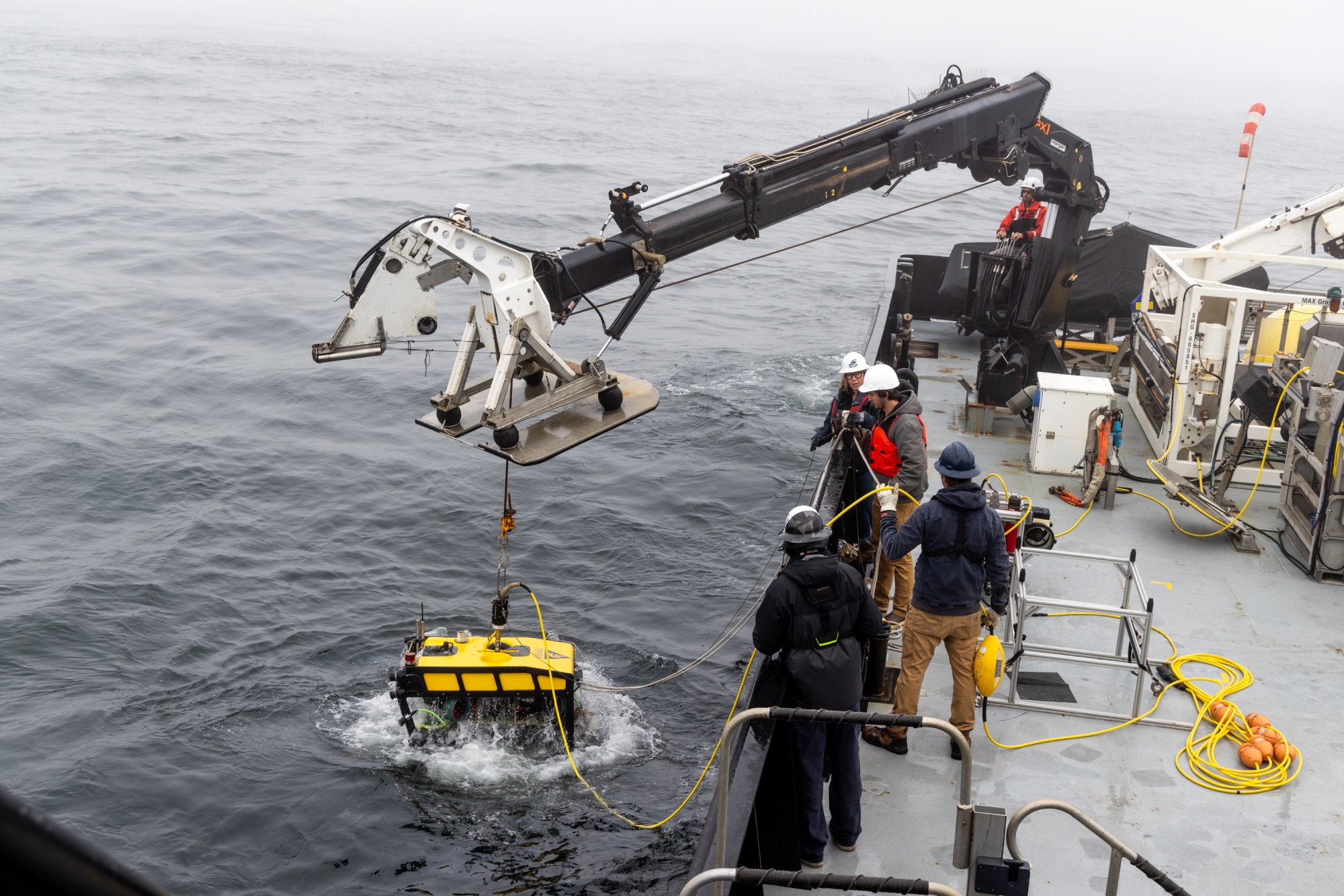

| By Todd Woody Nearly a dozen miles off the California coast on a foggy October morning, a crane lifts a boxy yellow robot off the deck of the research vessel Rachel Carson and lowers it into Monterey Bay's choppy gunmetal-gray waters. The remotely operated vehicle bristling with cameras and lights remains tethered to the ship by an unspooling cable but artificial intelligence has given it a mind of its own. The robot called MiniROV beams back images of a rarely seen jellyfish to a wall of screens lining a cramped control room aboard the ship. Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute principal engineer Kakani Katija lightly grips a pair of joysticks, maneuvering MiniROV closer to the translucent critter swimming through a marine snowstorm of organic particles falling to the seafloor.  MBARI researchers work with the MiniROV aboard the RV Rachel Carson in late October. Photographer: Rachel Bujalski/Bloomberg Then senior electrical engineer Paul Roberts presses a key on a laptop and announces, "We've started agent tracking." The "agent" is an AI program integrated into MiniROV's control algorithms. It's being deployed for the first time in the ocean, allowing the robot to autonomously locate and track marine organisms. Katija takes her hands off the joysticks and smiles as the robot begins following the square-shaped jellyfish of its own volition, firing thrusters to maintain pace with the animal as it rapidly swims away. To build an AI-powered network of ocean-monitoring robots, MBARI researchers are enlisting citizen scientists to play a game that helps train the machines at a rate much faster than a small group of researchers ever could. The need for speed is clear: The ocean is the world's bulwark against climate change and marine organisms play key roles in cycling carbon out of the atmosphere. Thanks to advances in robotics, underwater cameras and sensor technology, researchers have accumulated millions of images of deep-sea life, yet most creatures remain unknown. That's because classifying them can be a years-long endeavor constrained by the availability of overtaxed taxonomists. The jellyfish that MiniROV is tracking was first discovered in 1990 but wasn't identified until 2003 as a new species, Stellamedusa ventana. The game for phones and tablets — dubbed FathomVerse — populates a virtual ocean with images of marine critters in their deep-sea habitats stored in a sprawling database known as FathomNet. Some photos are of ocean animals whose identity has been verified by scientists. Others are organisms labeled by the AI or that have yet to be classified. Once players are trained up as amateur marine biologists, they take on missions drifting along ocean currents looking for pulsating dots that indicate where marine life has been recorded. Players tap the screen to see the animal and identify if it's familiar or tag it as unknown. The game then reveals whether their choices match the consensus of other players or if the creature remains undetermined. They win points for correct classifications as well as the number of organisms they spot. Players also score bonus points for correctly labeling a previously unidentified life form when consensus is reached. On the backend, researchers verify players' consensus findings and compare them to the AI's classifications. Chris Jackett, a research scientist at Australia's Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, says games like FathomVerse can play a significant role in training AI. "The human ability to recognize patterns and identify unusual features still remains unmatched, and having multiple observers examine the same imagery helps build robust training datasets," says Jackett, who works on AI detection and identification of corals and other marine species. Read the full story to find out how many images players have identified and MBARI researchers' next steps. Subscribe for even more climate and ocean news.  Lowering the MiniROV into the Pacific. Photographer: Rachel Bujalski/Bloomberg |

No comments:

Post a Comment