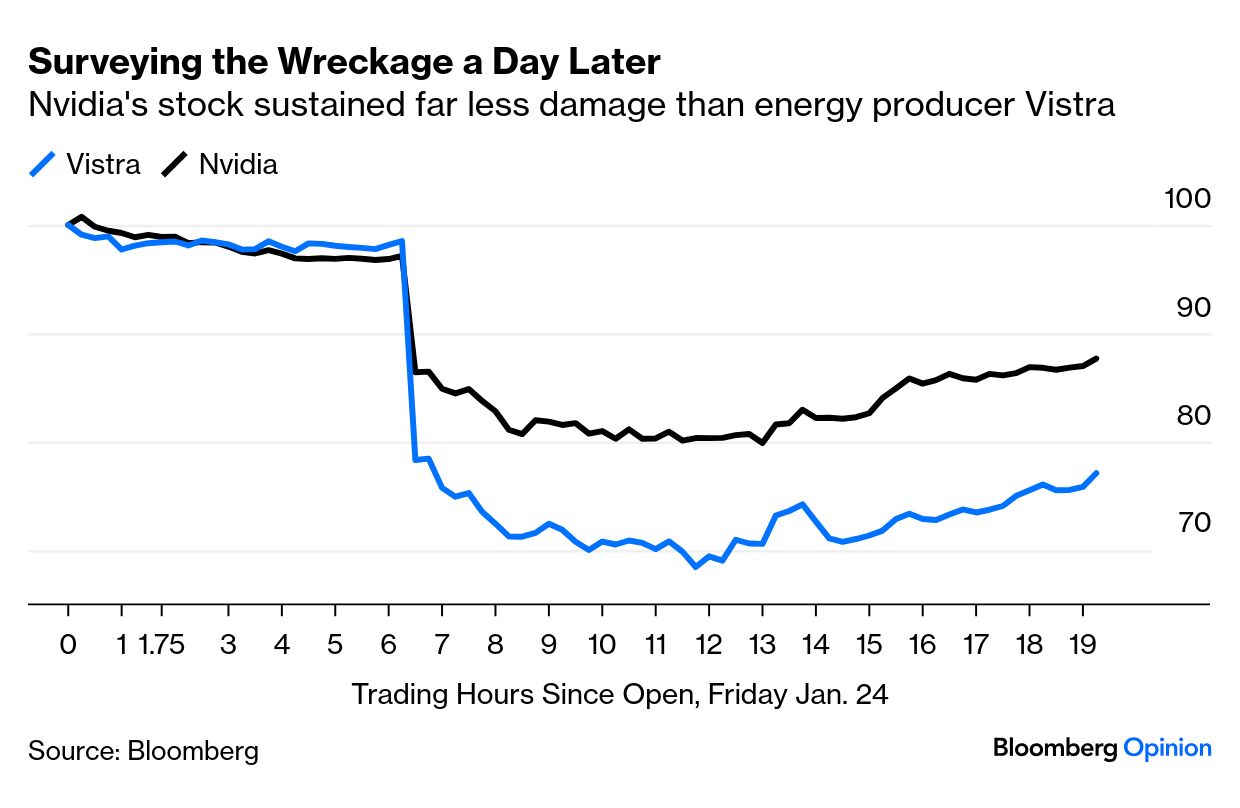

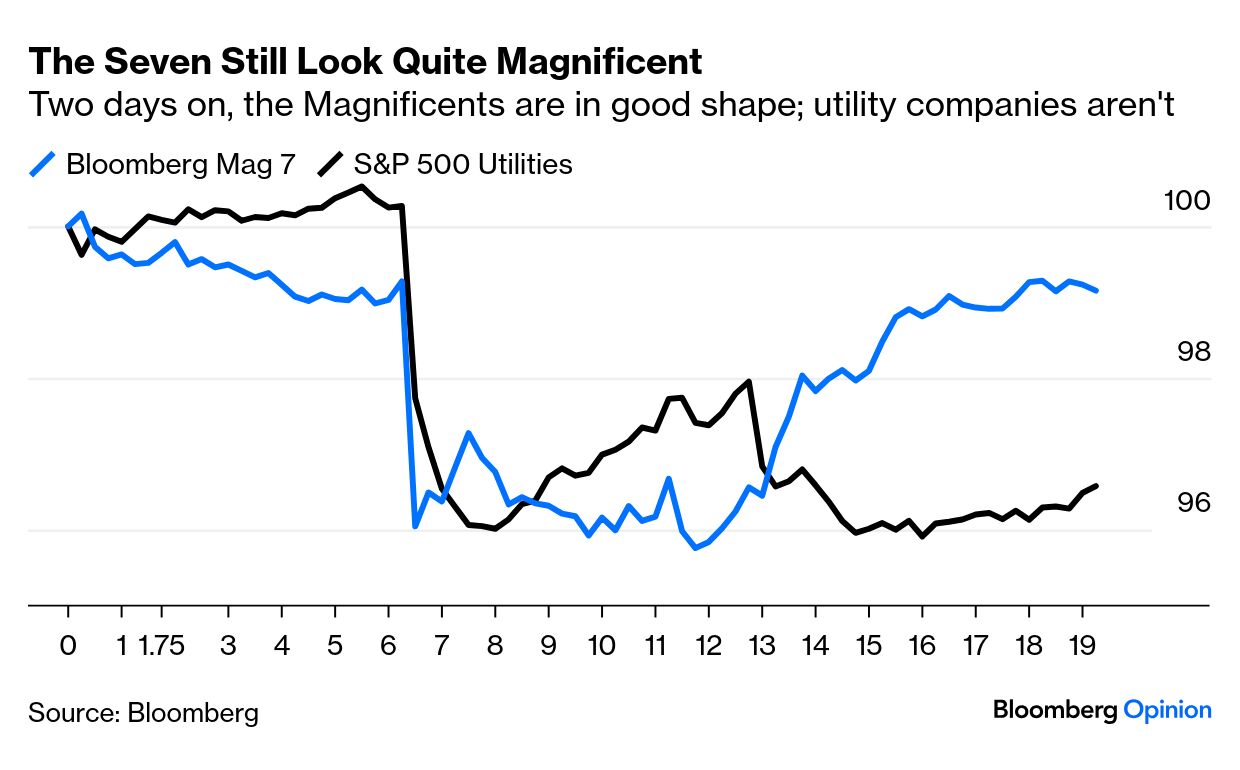

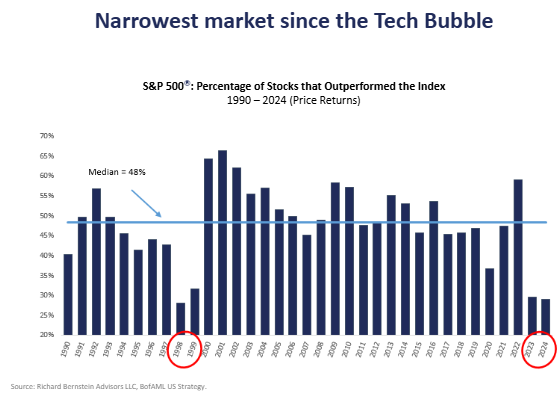

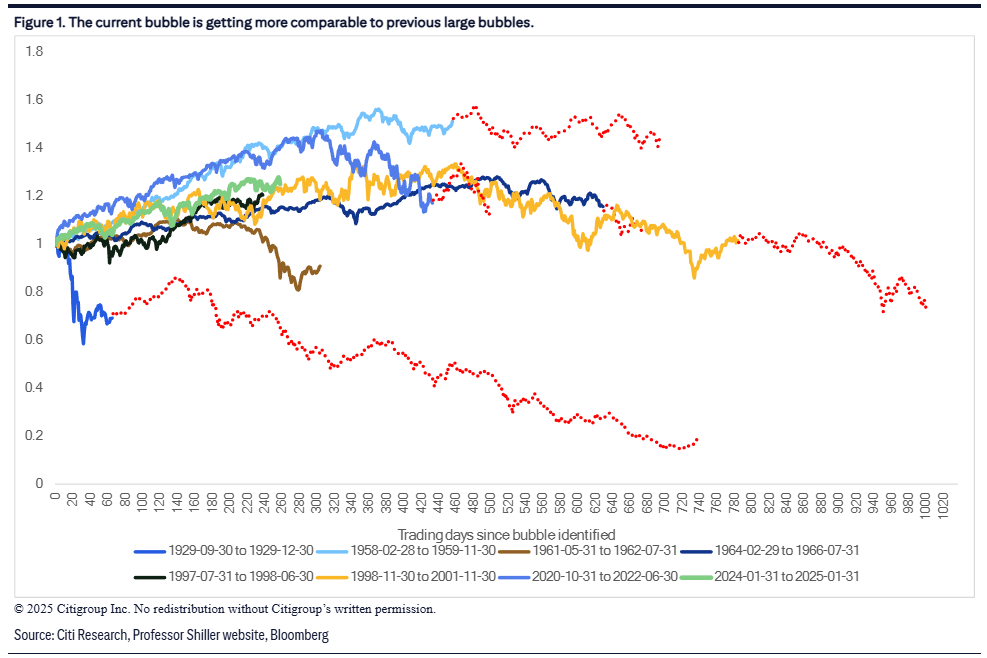

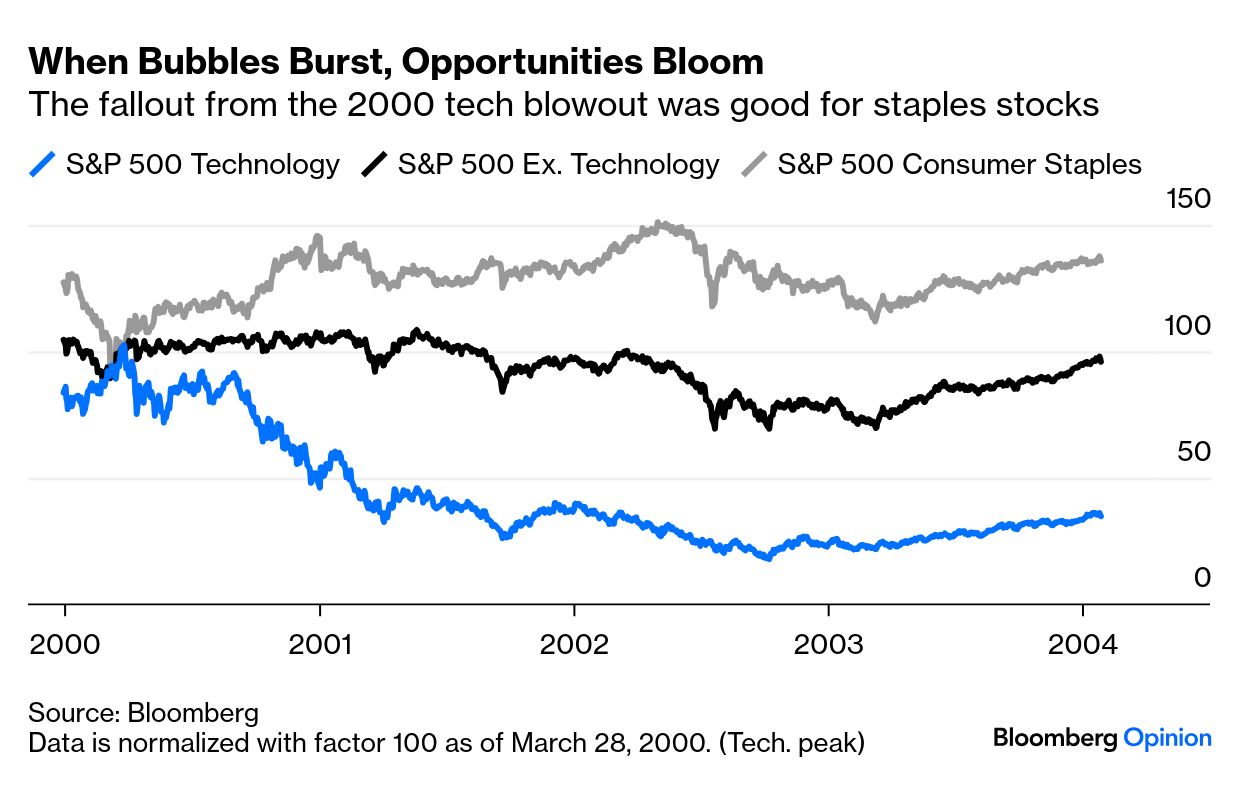

| In The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, humans build the greatest computer ever, called Deep Thought, to answer the "ultimate question of life, the universe and everything." After millions of years to think about it, it spits out the answer: 42. That leaves them even more confused, and needing to know what the question was. There are parallels with the attempt to understand the ramifications of DeepSeek, the new Chinese-made competitor to ChatGPT that appears to operate with far less computing or electrical power than artificial intelligence models to date. It will take time to sort out how much DeepSeek changes the economics of AI. For now, here are some of the deeper thoughts as people try to work out the question they most need to ask. Day Two: Markets bounced, as might be expected, without regaining all the ground lost on Monday. But while Nvidia Inc., whose value dropped by $580 billion, staged a decent recovery, the ongoing damage seems worse for the utility companies that stood to provide the extra power to keep AI data centers running. Worst performer in this sector was Vistra Corp.: At a sectoral level, this effect was dramatic. The interests of the Magnificent Seven technology platforms aren't in total alignment, and they often compete against each other. The other Magnificents are Nvidia's biggest customers, and so would be among the biggest gainers if they don't need to spend so much on capex. They have almost got back to where they were on Friday. The same is not true of the S&P 500 utilities index: Bubbles If the Magnificents had formed a bubble, then, it still hasn't burst. But Monday's sell-off shows that the story of Magnificent exceptionalism isn't strongly rooted. Diagnosing bubbles in real time is difficult (and history is often compromised by our failure to include the market rallies that turned out not to be bubbles and didn't burst). However, a market this dependent on a few stocks is a bad sign. This chart is from Bank of America Inc.'s Michael Hartnett: "Narrow markets are the exception, because of capitalism," says Richard Bernstein of Richard Bernstein Advisors. "You'll find through time that these narrow markets, when people think only a few companies have a future, turn out to be a lot of speculation." The question is why this would change. He added that with the US stock market now representing a record-high percentage of global market cap, "US exceptionalism was the argument to make 15 years ago. It's not an argument for today." Dirk Willer and the macro strategy team at Citigroup Global Markets offered this chart of past burst bubbles. In all cases, they only start when a market has reached the definition proposed by the renowned fund manager and stock market historian, Jeremy Grantham, which is to exceed the long-run price trend by more than two standard deviations. This incident does look quite a lot like one of those: Recognizing that it's not going to be possible, or wise, to try and time the top, the chart instead suggests a system of waiting until the market is down either 15%, or back to the two-standard-deviations level, signaling that the bubble is over, and then selling to enjoy the proceeds as it further deflates. The red-dotted lines show how this would work — spectacularly successful after the Great Crash and also after the dot-com bubble. In the other incidents, the approach didn't work so well. Alternatively, Bernstein points out that imbalanced rallies, like that of 1998-2000, are followed by similarly imbalanced denouements. After the tech bubble peaked, the overall market fell for years, but there were plenty of opportunities. Maybe try looking for them again now: An asset class that could generate as much as $30 trillion will not run out of suitors quickly. Private credit fills the critical void left by banks hamstrung by new regulations. BlackRock Inc.'s $12 billion acquisition of HPS Investment Partners in December epitomized the confidence in the growing investment category. Is it justified? It's still creating opportunities for both old players and new entrants. They stem from lenders' ingenuity, macroeconomic conditions, and changing regulations. The asset management industry's push to make it easier for 401(k) plans to invest in private credit and private equity could help. The backlash against ESG investing has seen a focus on the rules that govern 401(k)s. As Points of Return noted, unlike US President Donald Trump, pension executives are generally admirers of ESG. Would Trump be open to granting access to these funds whose managers follow ESG goals? Samuel Dale, research lead on private markets at With Intelligence, takes a nuanced approach to opening up pensions to private credit: If you're an individual investor or pension investor, a strong positive is that you get different returns, which you probably don't have much exposure to. There have been structural things that are driving decent private credit returns. There are more alternative products out there. Some banks have pulled back from lending, creating more of a demand in the middle market. On the negative side, you potentially would lock your money up for longer. Maybe that's okay if you're a 401k investor, but if you're an individual investor outside of a 401k, you might not want to.

Even if it doesn't get a share of 401(k) money, private credit's evolution continues unabated. With Intelligence notes that regulatory changes, such as the Basel III Endgame proposal, will likely accelerate banks' retrenchment, driving money toward private debt managers. This migration can't happen overnight. Torsten Slok, chief economist at Apollo Global Management, expects the relationship between banks and private credit firms to grow more symbiotic through strategic alliances: Initially targeted at the sub-investment grade market, we expect these partnerships will eventually extend to investment-grade companies as well. While public IG funding is widely accessible, the lack of flexible financing solutions available today can create an opportunity for private credit providers.

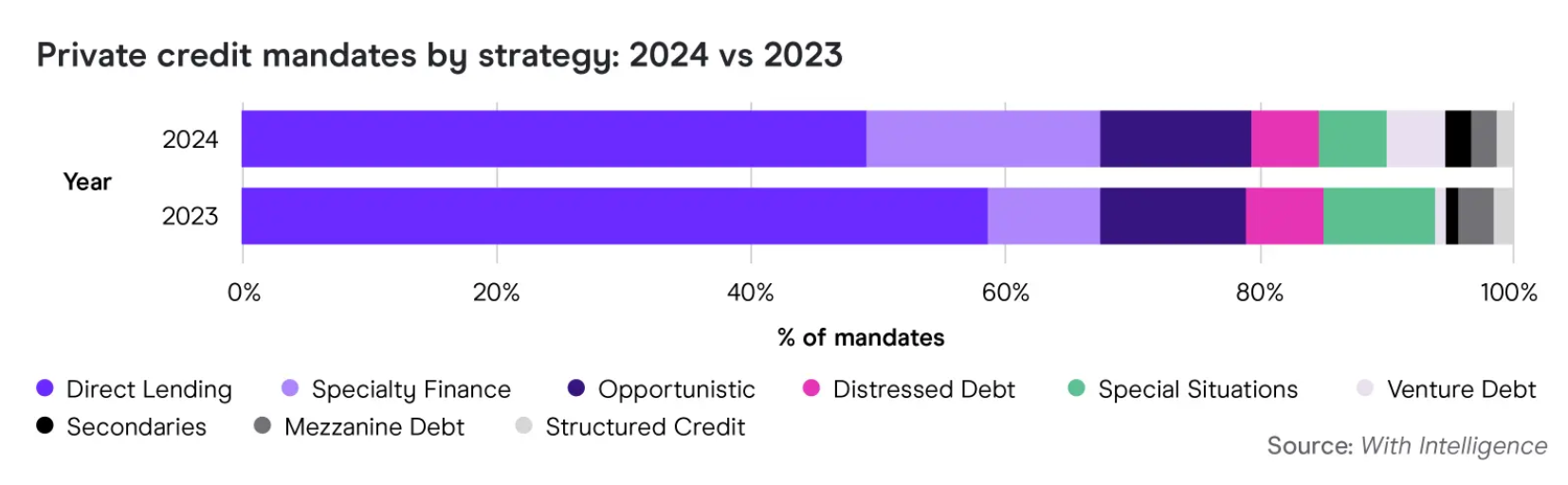

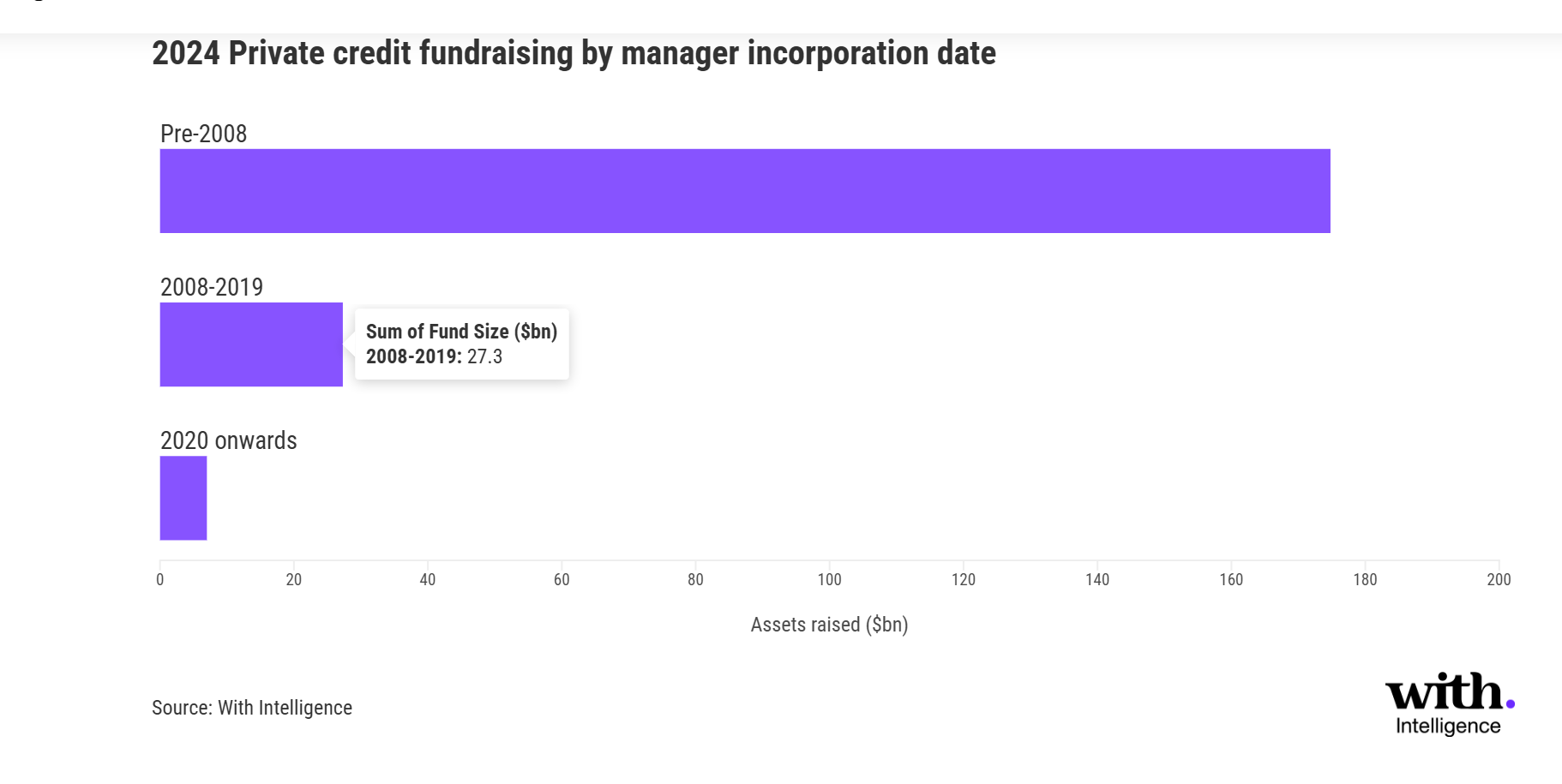

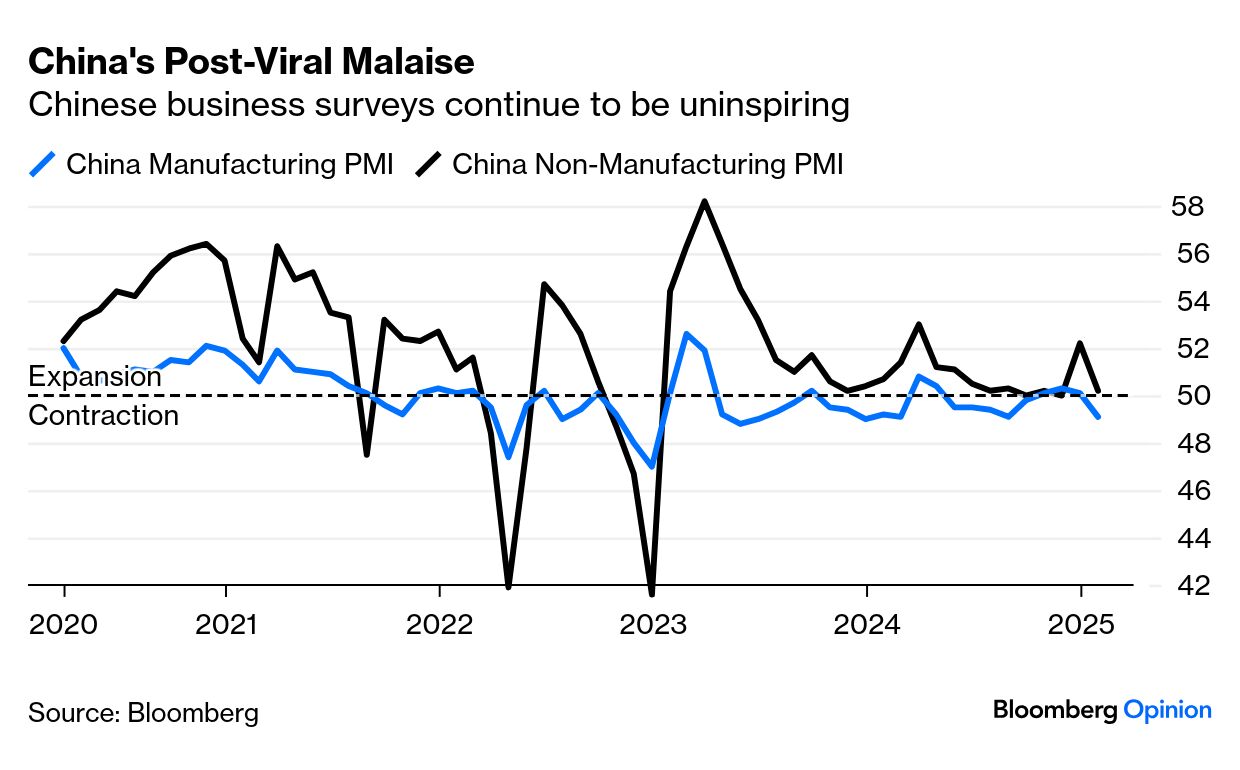

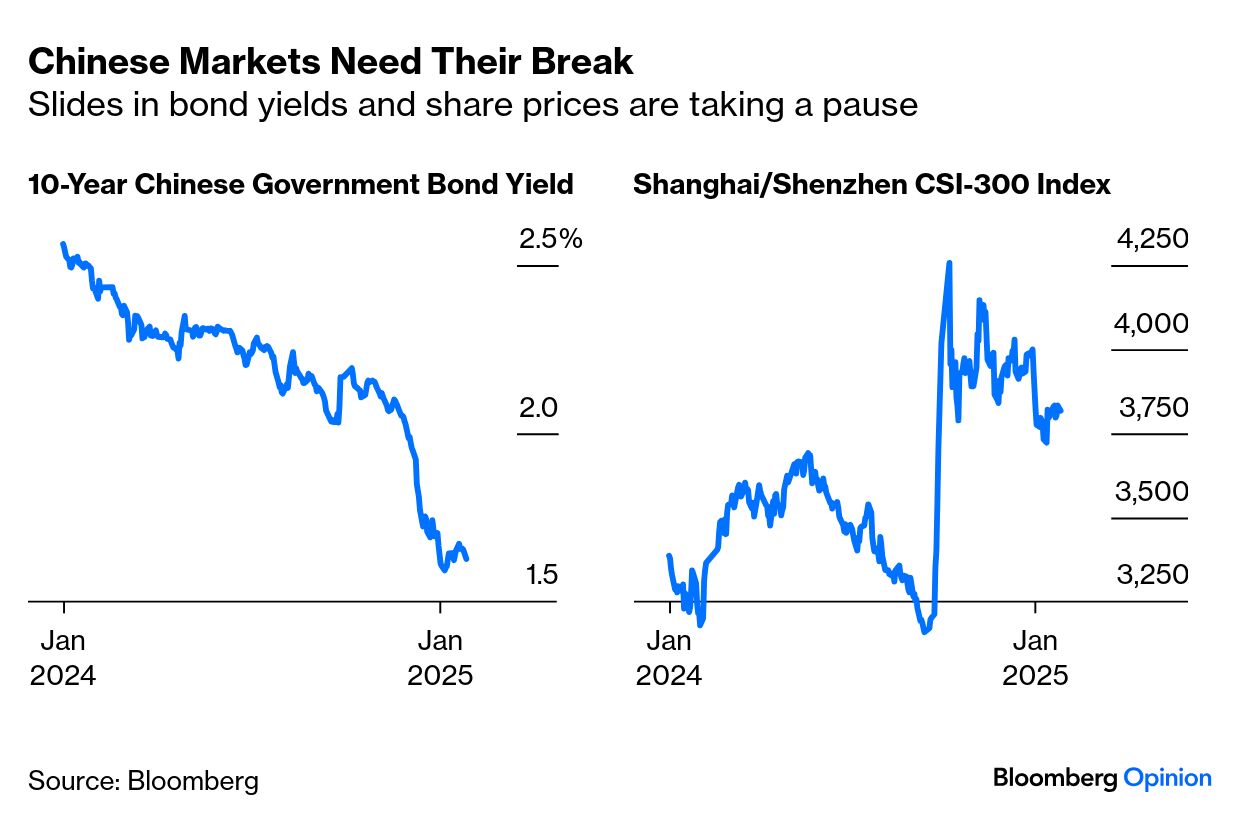

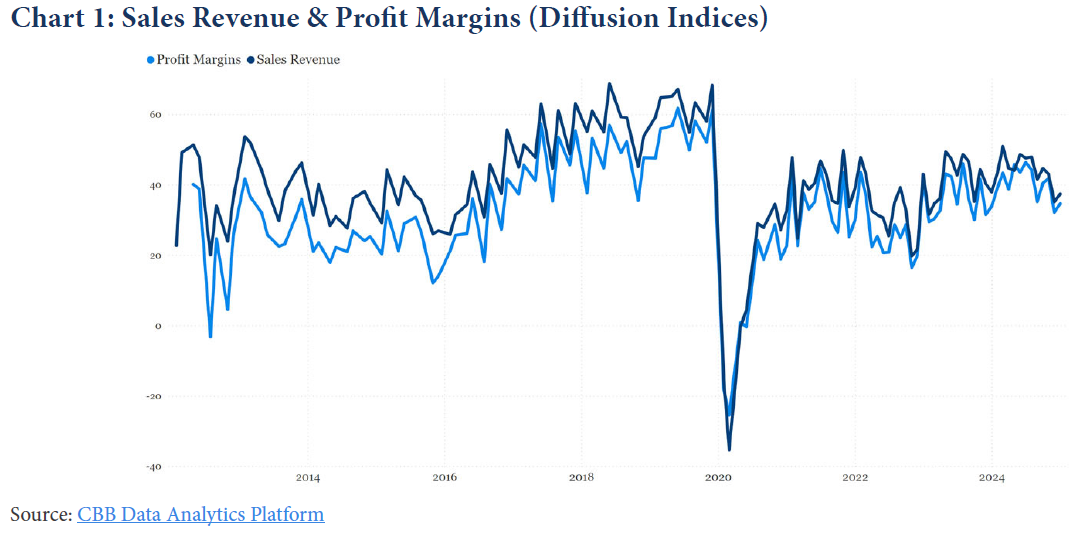

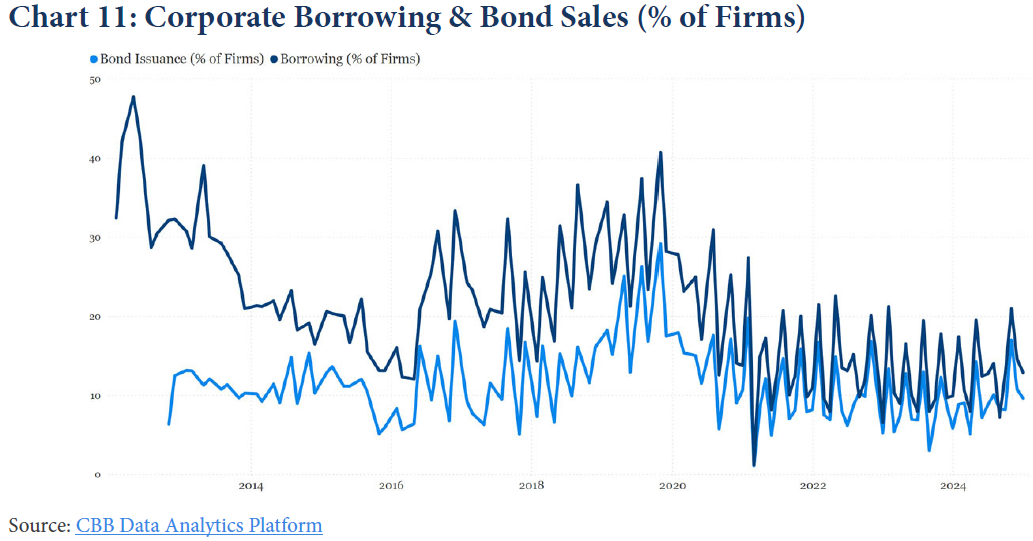

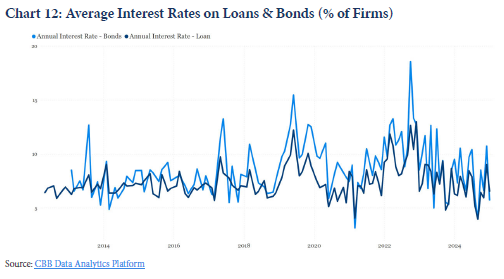

What are these opportunities, and how substantial are they? Specialty finance — asset-based lending occurring outside traditional banking and commercial real estate channels that is secured by financial or hard assets — comes to mind. PIMCO Investments estimates its US addressable market value at $20 trillion. However, unlike direct lending, where scale is paramount, With Intelligence's Dale argues that specialty credit allows new entrants to differentiate themselves. The proportion of new launches running non-direct lending strategies is increasing. Between them, specialty finance and opportunistic credit — a flexible investing approach spanning the full range of private credit strategies — accounted for 30% of the mandates Dale's team tracked in 2024, up from 21% in 2023: Still, it's tricky for a first-time manager to succeed in private credit. Dale notes that experience dealing with distressed credit events (generally from those who were in the industry before 2008) is crucial for those looking for talent. That's because the increasing strain on portfolio companies in a higher-for-longer rate environment makes such experience vital. This With Intelligence's chart bears that out: This entry barrier may be driving M&A, as companies try to acquire established private credit teams. Morgan Stanley analysts predict Trump's "lighter touch" approach to regulation should provide further tailwind for such deals, and that optimism could filter down to activity financed by private credit. Prior to Trump 2.0, private credit's growth had been prompting talk about greater regulatory oversight. That looks a little less likely now. Banking sector deregulation might also eventually work to the advantage of private lenders as it would allow more capital deployment, including to non-bank lenders. Morgan Stanley analysts add that banks could serve a wider range of market participants in ways that consume less capital and drive stronger overall returns. The largest opportunities are in financing alternative managers, private credit funds, and the assets underlying these portfolios. Regulation spurred private credit's growth; deregulation might help it further. -- Richard Abbey After lobbing its DeepSeeking hand grenade into American self-confidence on Inauguration Day, China can now enjoy its new-year break. It's entitled to hope that the Year of the Snake is better for its fortunes. The latest purchasing managing index surveys of business in manufacturing and services, published at the weekend, showed that China remains downbeat — as it has been for most of the time since the pandemic began in 2020: These numbers are uninspiring, but could be much worse. Ditto for the financial markets. Bond yields remain close to historic lows, which suggests minimal confidence in a truly difference-making stimulus. Stocks enjoyed a short-lived but dramatic rally last September, when it briefly appeared that a big attempt to prime the pump was on the way. They haven't returned to the lows, but they have given up much of that rally: What does this suggest for the future? China Beige Book, the research group, publishes its latest survey today (and finds a situation that is thoroughly unexciting, but with no imminent risk of a crisis). The consumer, as measured by sales revenues and profit margins, is in better shape than for much of the post-pandemic period, and roughly back to the levels seen in the middle of the last decade: Meanwhile, despite record low bond yields, corporate borrowing and bond issuance remains startlingly low: At the same time, the cost of financing is almost as cheap as it ever gets: China Beige Book's Shehzad Qazi summarizes this in a way that need not excite or terrify anyone: Our data indicate Beijing feels little pressure to unleash historic levels of stimulus spending, even if it's capable of doing so. Current accommodating words and inactions from Trump on tariffs reinforce that view.

Now to see if it still looks that way after the Lunar New Year break. Some videos to catch up with DeepSeek. Jon Stewart points out with devastating understatement that it shouldn't be surprising that China can make things cheaper. And I got to talk about the whale in Nvidia's moat in a video our team put up, where else, but on TikTok. Also yesterday, I forgot to mention Satellites by Doves. Sorry. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: - Nir Kaissar: Nvidia's Stock Crash Solves a Wall Street Puzzle

- Marcus Ashworth: Trump Bluster Alone Won't Budge King Dollar

- Mohamed El-Erian: The Fed Will Duck and Weave on Policy, But Not for Long

Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN . Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment