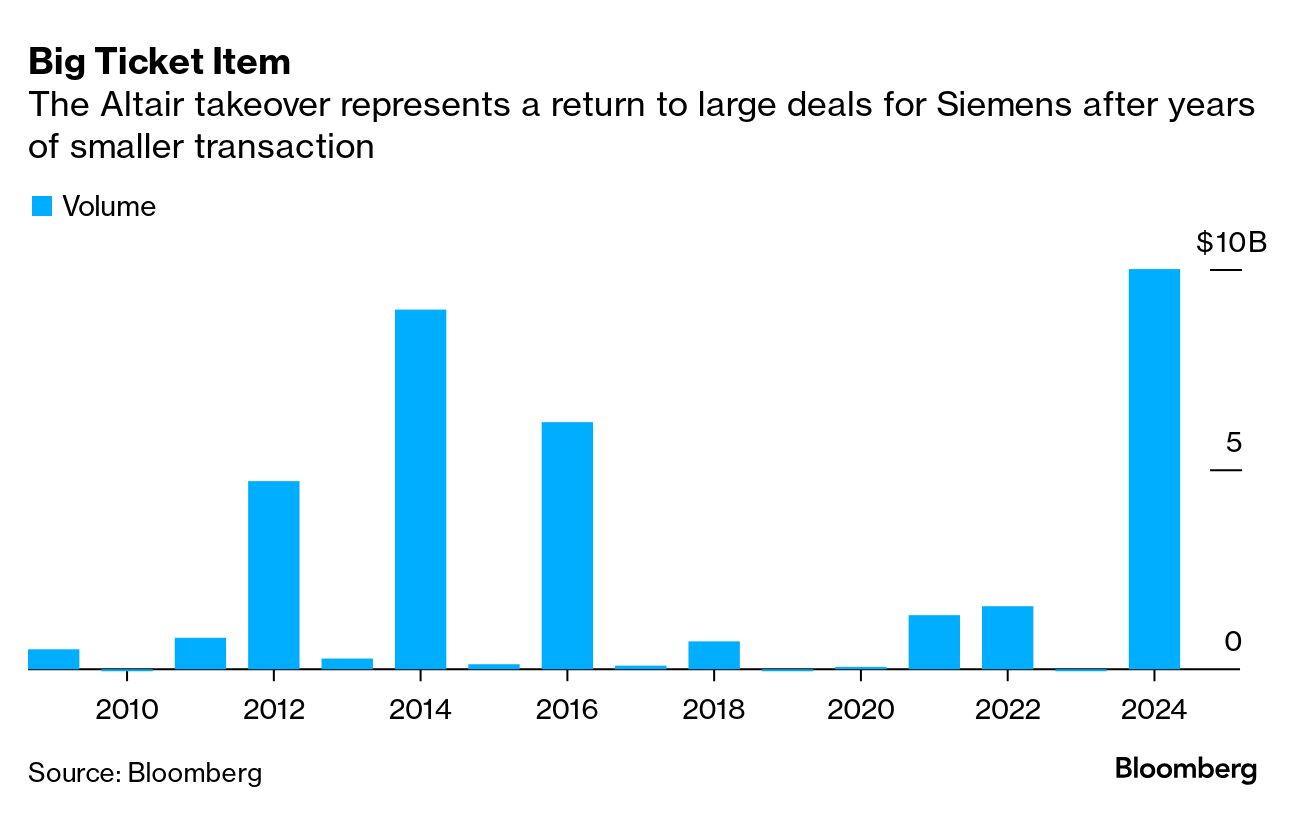

| Have thoughts or feedback? Anything I missed this week? Email me at bsutherland7@bloomberg.net. Also a programming note, there will be no Industrial Strength next week. Look for the next one on Nov. 15. To get Industrial Strength delivered directly to your inbox, sign up here. Siemens AG's $10 billion acquisition of software company Altair Engineering Inc. represents one of the biggest bets yet that the future of the digital world is yoked to hunks of metal. The Altair takeover announced this week is the largest ever for Siemens, which traces its roots back to 1847, and caps a string of more than 40 software acquisitions by the manufacturing giant worth more than $20 billion combined. It's also one of the biggest software company takeovers by any public industrial acquirer. The goal is to deepen Siemens' expertise in higher-margin software services that link back to and make sense of the reams of data collected from the physical world, whether that's the factory floor, a building or the grid. Altair specializes in simulation software that can be used to test the point at which a smart watch might break if it's dropped as well as the risks of electric vehicle batteries exploding in a crash or ear buds picking up interference from a neighbor. While Siemens already had expertise in manufacturing design software and predictive maintenance, Altair's simulation tools — particularly for mechanical or electromagnetic applications — were the missing piece in creating more effective digital mockups that can be used to fine tune operations in the real world, Siemens Chief Executive Officer Roland Busch said in an interview this week. "It's like finding a diamond somewhere," he said. Like a diamond, Altair is expensive: With a price tag of $113 a share, Siemens' offer values the software maker at more than 30 times its expected adjusted earnings next year after backing out the value of targeted cost savings, according to Jefferies analyst Simon Toennessen. That's a normal valuation for a software acquisition but quite a rich one in the industrial world and that raises the burden of proof for Siemens on the logic of choosing a software company for its largest ever deal. Its second-largest takeover was of a decidedly different breed: the $7.6 billion purchase of oilfield equipment manufacturer Dresser-Rand Group Inc. announced in 2014.  The Dresser-Rand business is now part of Siemens Energy AG, which the parent company spun off in 2020 as part of a broader push to simplify the sprawling conglomerate. Siemens Healthineers AG, the company's medical imaging and laboratory diagnostics business, went public as a standalone entity in 2018. Other more recent divestitures include the sale of the Innomotics heavy-duty motors operations to private equity firm KPS Capital Partners for €3.5 billion and a separate deal announced this week for Siemens' airport logistics arm. But Siemens does still make plenty of physical stuff: The company manufactures automation technologies, electrical equipment used to power data centers, building systems and high-speed rail cars, among other things.

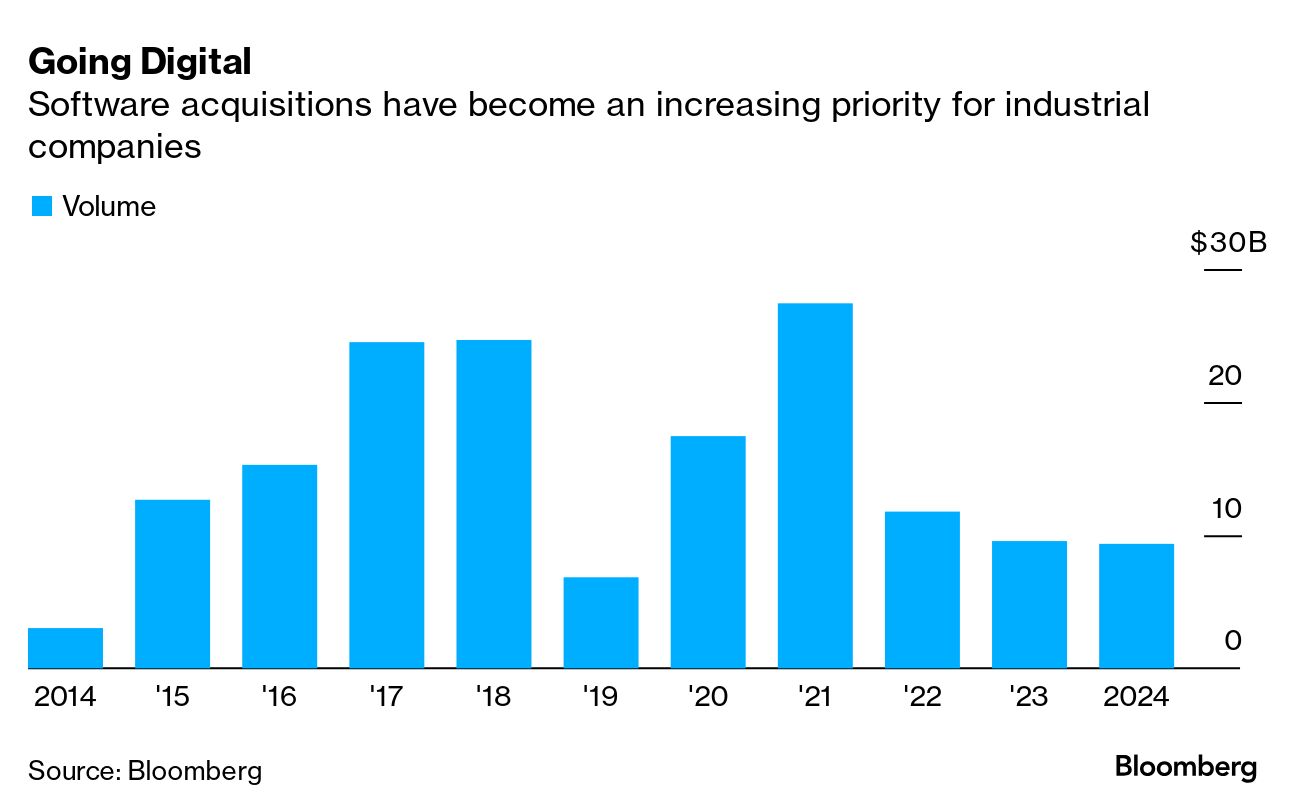

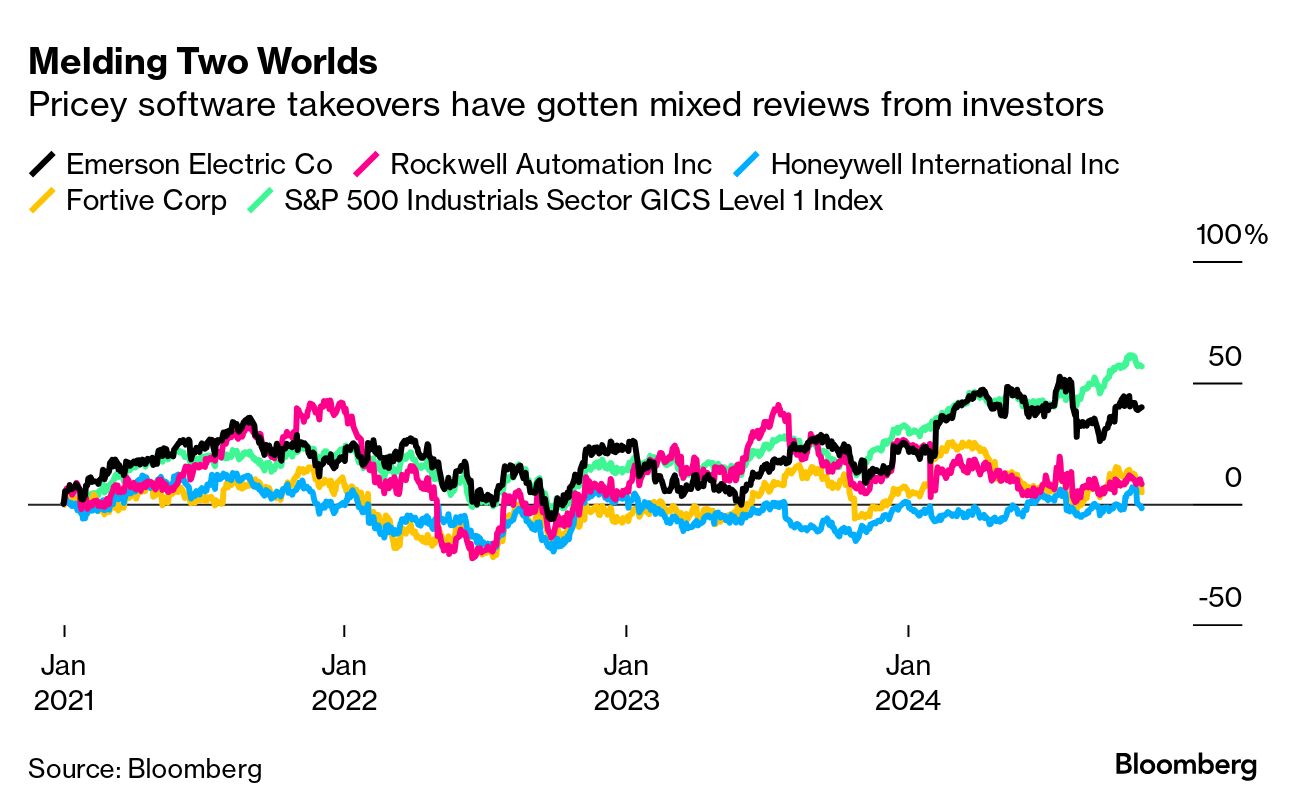

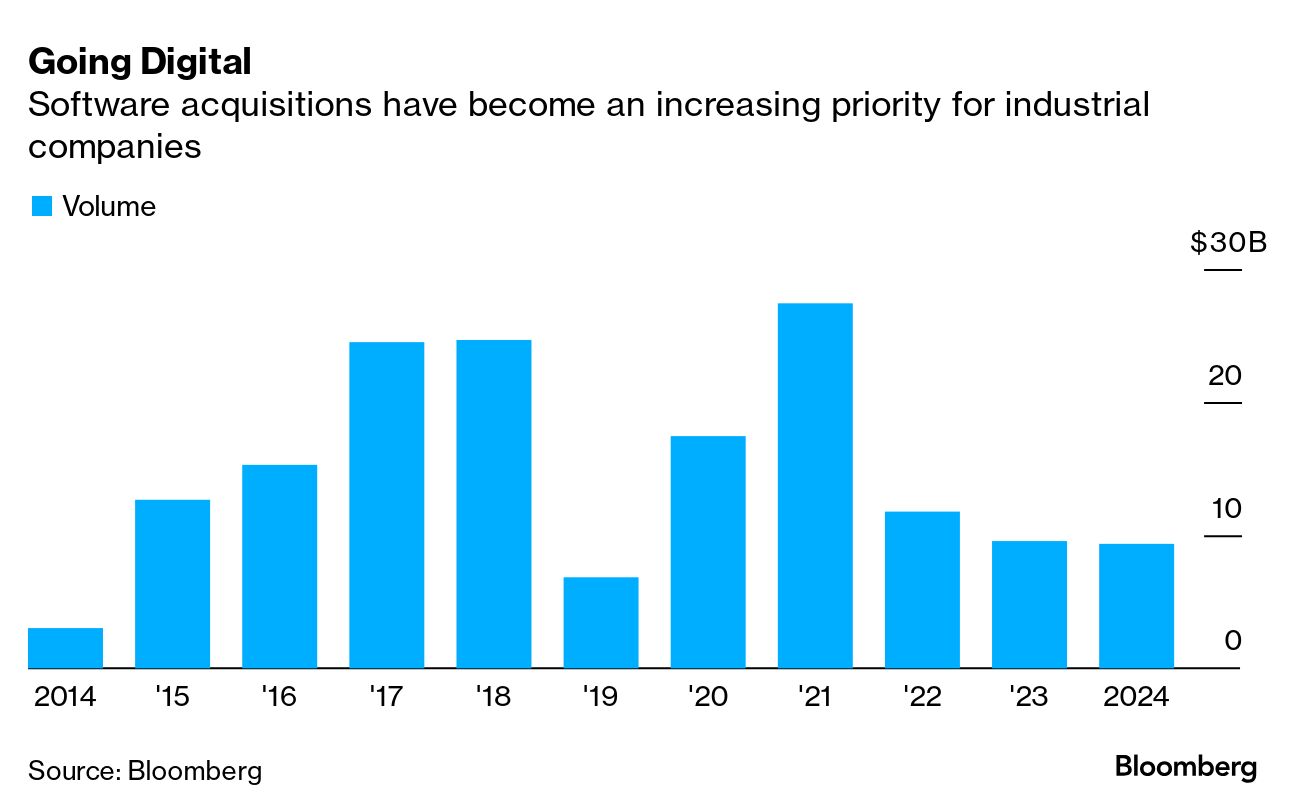

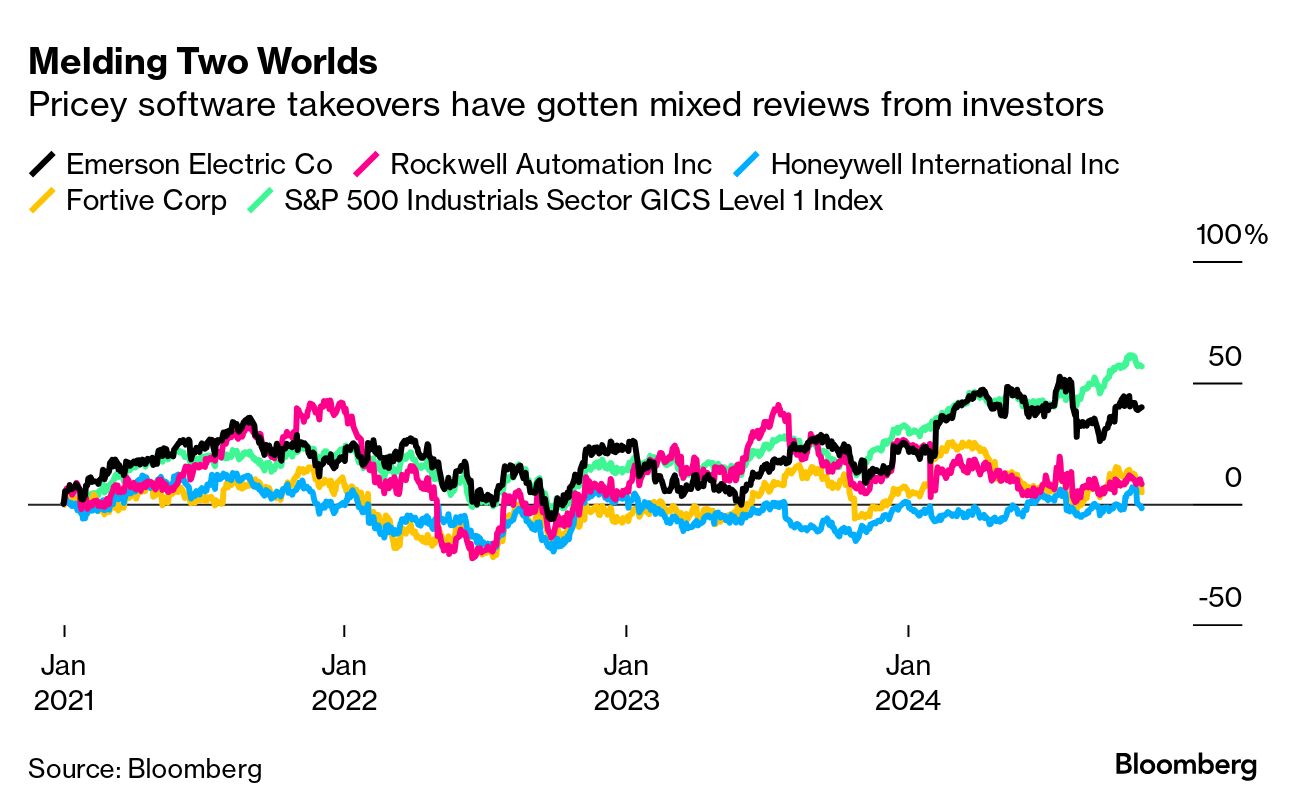

Busch said he's often asked if Siemens' growing software operations should stand on their own but that such a scenario would shortchange the businesses. By pairing the software acquisitions and Siemens' manufacturing heritage together, both sides are more valuable than either would be on their own, he said. Read more: Why Build a New Factory in US? Not Politics Software reduces development turnarounds for new technologies and can help manufacturers avoid costly downtime by predicting when equipment will need repairs. Simulation capabilities limit the need to actually physically break things in the testing process (and the waste associated with that). But the hardware provides the data that feeds industrial software and emerging artificial intelligence applications and actually knowing how physical equipment is made and used can be helpful in interpreting whatever kind of insights the digital world spits out, Busch said. "When some hyperscalers try to bring their software stack to the automotive industry, writing some applications on the data and throwing the AI experts on it, yeah they found out something happens there, but then what? And we know what to do with the results," Busch said. "The beauty about Siemens' business is that we are living in both worlds," Busch said. "Siemens is a leading technology company and we are also a leading software company." He's not the first to make this sales pitch: General Electric Co. infamously billed itself as "the digital industrial company," before its aspirations of becoming a top 10 software giant fizzled out alongside its cash flow. Honeywell International Inc. called itself a "software-industrial company" for a while and now talks about its "digital backbone." Emerson Electric Co. is also a "global technology and software company," while electrical and automation equipment manufacturer Schneider Electric SE says its mission is to be customers' "digital partner for sustainability and efficiency."  Collectively, publicly traded industrial companies have spent more than $75 billion on acquisitions of software companies since the start of 2020, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. These acquisitions have not been particularly popular with investors, in part because they tend to be expensive and it's not always obvious after the fact what the benefit was to the company's underlying sales and profitability. In the US, manufacturers that have pursued large software acquisitions in the post-pandemic era — including Emerson, Honeywell, Fortive Corp. and Rockwell Automation Inc. — have underperformed broader industrial benchmarks. Siemens itself trades at about 13 times its expected fiscal 2025 earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization, while German software giant SAP SE trades for 23 times.  It's incredibly difficult to convince investors to treat a legacy industrial manufacturer like a software company — particularly if the bulk of its business is still centered around physical equipment and the earnings swings that tend to accompany that. But even Roper Technologies Inc., which got its start as a pump and valve manufacturer but now almost exclusively sells niche software services, is in the bottom third of performers on the S&P 500 Information Technology Index so far this year. The inverse is much easier: Microsoft Corp. makes laptops and gaming consoles, while Alphabet Inc. makes doorbells, cameras and smoke detectors and Amazon.com Inc. makes speakers and tablets. But the alternative for industrial acquirers is to cede the digital realm to technology giants, and that has risks as well. While artificial intelligence might eventually replace some human jobs, it's not going to eradicate the factory floor altogether. "The world loves IT, right? But it runs on operational technology," Busch said. "We have a great business and we've been over-performing in China for a long time. We made a decision to change our credit policy, specifically around down payments and progress payments. And long term, this will be the right decision." — Trane Technologies Plc CEO Dave Regnery Regnery made the comments this week on Trane's earnings call after the heating and air conditioner company reported a 50% slide in orders from China and a 45% slump in revenue from the country in the third quarter. It's not exactly a surprise that property and construction markets in China are under pressure; China has announced a slew of stimulus measures in recent weeks and is reportedly weighing even more extensive fiscal support. Sluggish demand from China has weighed on industrial companies' results for an extended period. Separately this week, elevator maker Otis Worldwide Corp. cut its full year guidance amid a deepening slump in new equipment orders from China. "China remains a question mark," CEO Judy Marks said. The company is currently forecasting as much as a 10% decline in unit sales in China in 2025, although the ultimate results are "clearly dependent on the impact of government stimulus measures," she said. But Trane had largely avoided that weakness, in part because it primarily supplies industrial facilities, rather than office buildings. For example, in the second quarter, Trane's orders from China were up mid-single digits relative to the same period the prior year. And then the streak broke, suddenly and dramatically.

China makes up just 4% of Trane's sales so the slump in that market is more than offset by continued strong demand for commercial-grade equipment in the US and Europe. But the company's decision to tighten its credit policy suggests a different attitude among manufacturers to an economy that for a long time was the primary growth engine for industrial markets. "If a customer wants to give us an order and they don't give us a down payment with that, we will not accept the order. If we have a product that's complete and ready to ship to the customer and the customer doesn't provide the proper down payment or progress payments, we will not ship that product to the customer," Regnery said. The company doesn't want to prioritize the short-term benefit of an extra order or dollar of revenue and then "three, six, nine months down the road, you wind up with a problem you have to deal with," added Chief Financial Officer Chris Kuehn. - Lost decade of plane output costs airlines thousands of jets with no end in sight

- Ports race against political clock to lock up $3 billion of clean energy grants

- Private jet company taps muni bond market for Austin airport expansion

- Shrinking stockpiles of air defense missiles raise alarms about US readiness

- Ford to pause work at Michigan factory for F-150 Lightning on weak EV demand

- Airbus hires new commercial chief, keeps delivery goal despite supply snarls

- Volkswagen embarks on drastic restructuring amid flagging profits

- Brookfield buys $2.3 billion stake in four Orsted offshore UK wind farms

- There's a lot to consider when picking a site for a US factory

- The trucking recovery will be slow: Talking Transports

- United Airlines makes loyalty perks harder to get

- US Air Force paid a 7,943% markup for soap dispensers on Boeing planes

|

No comments:

Post a Comment