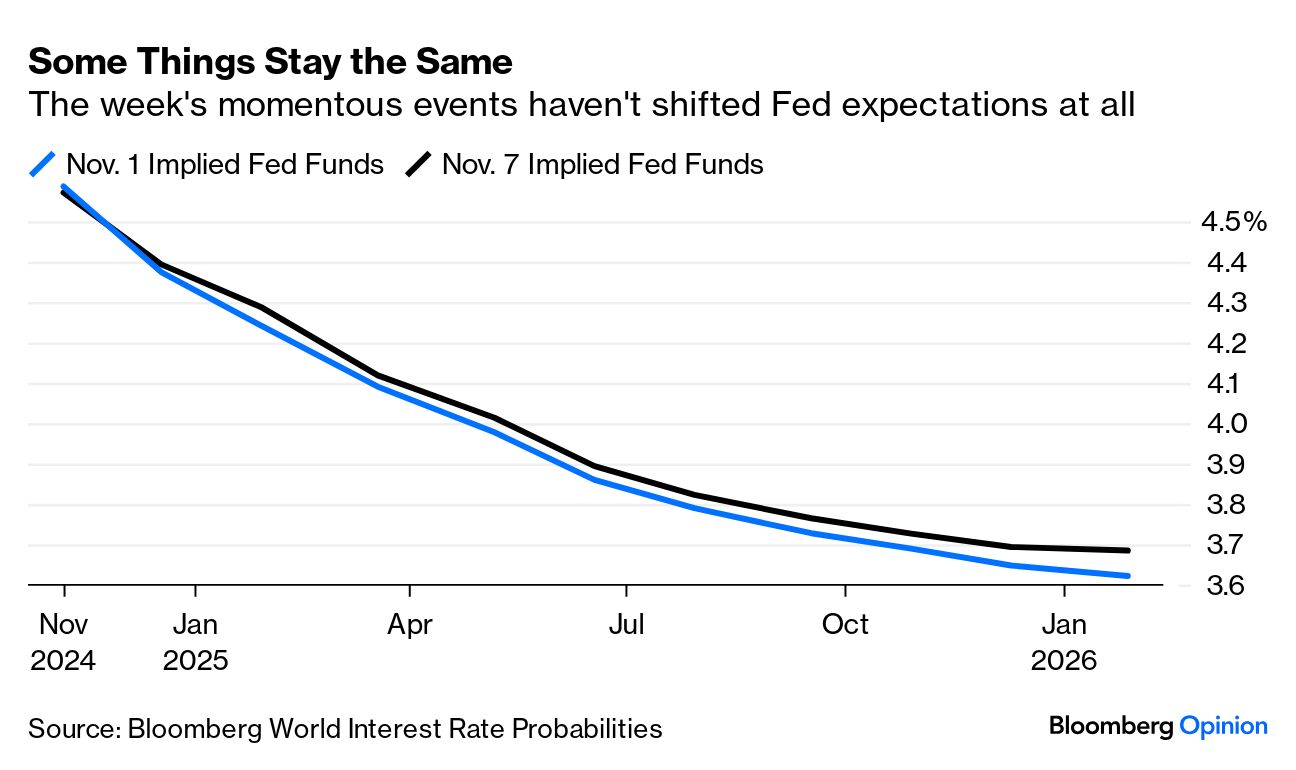

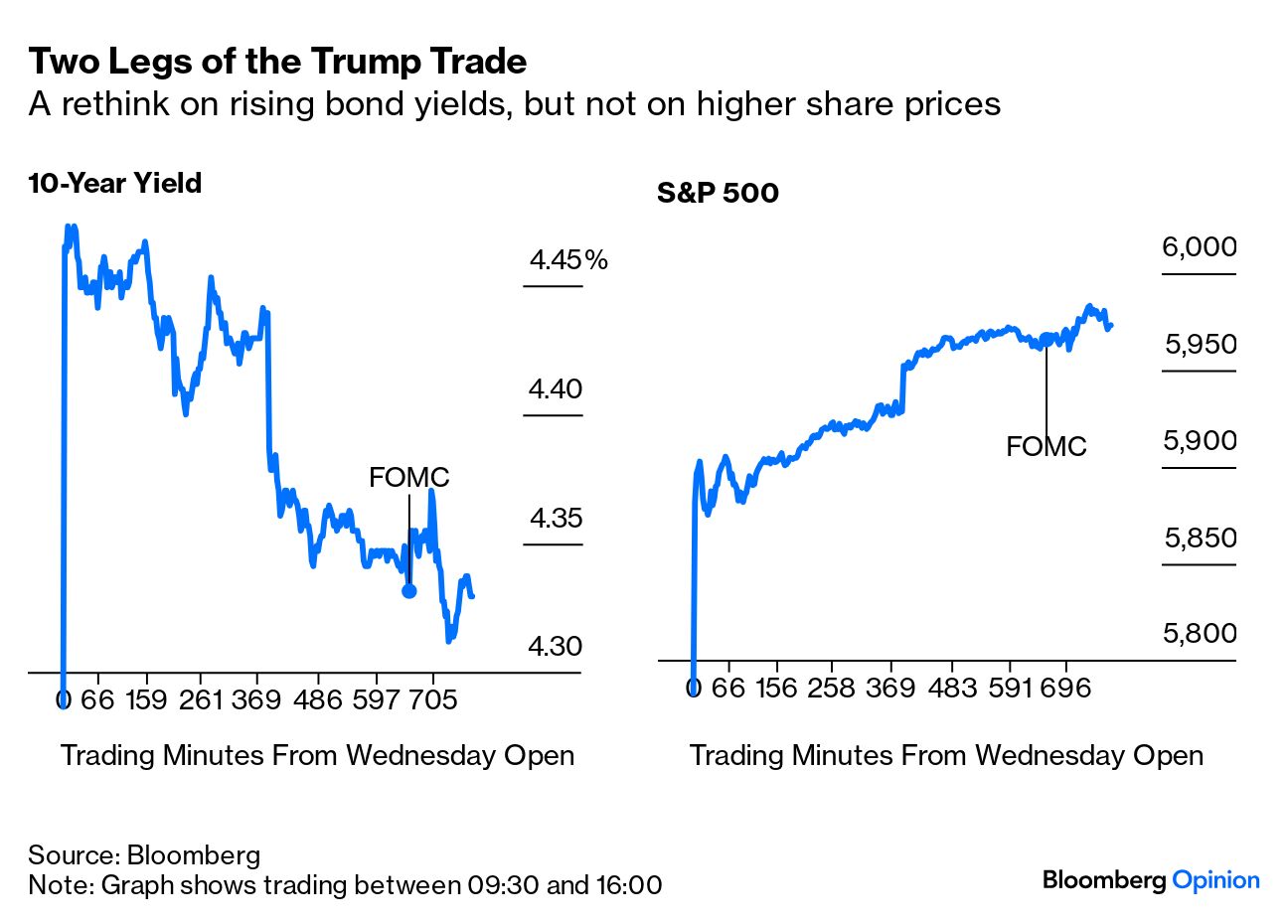

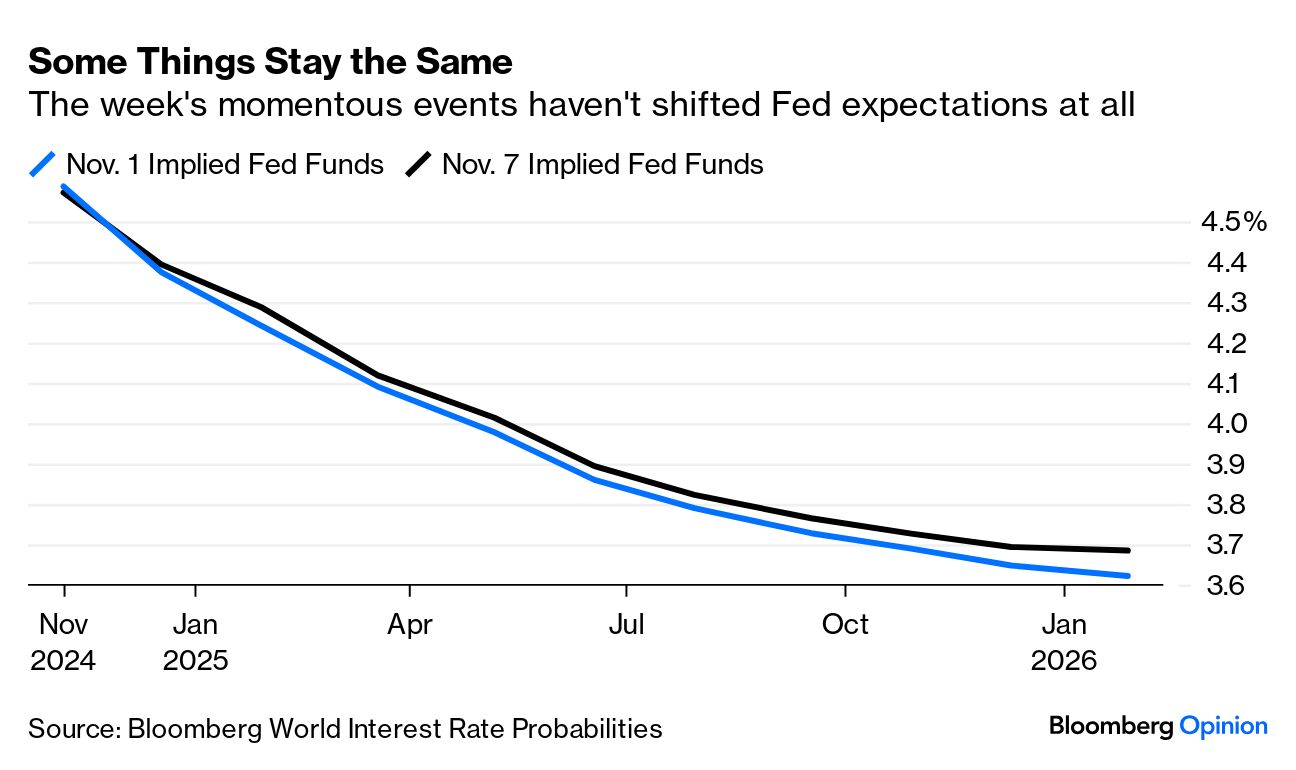

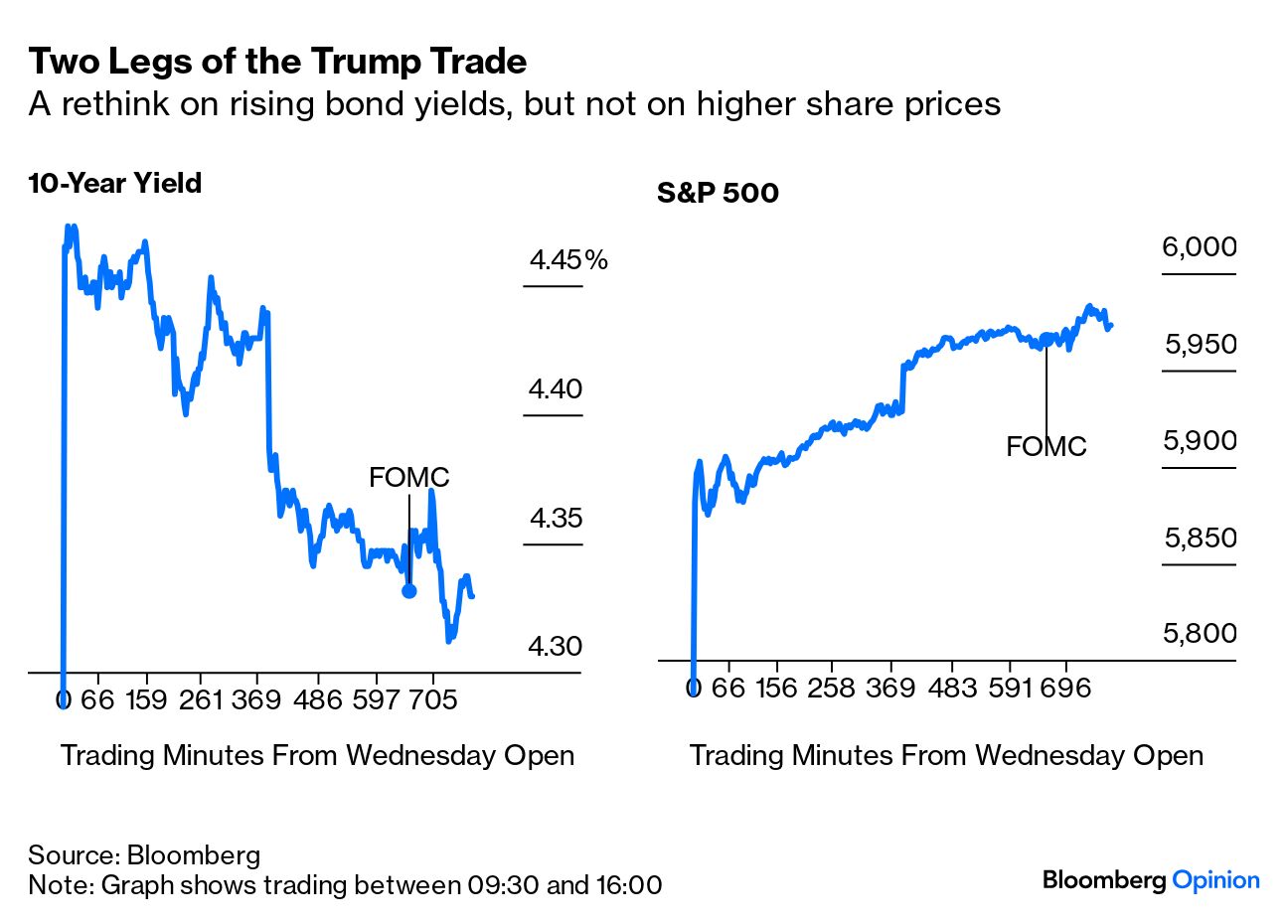

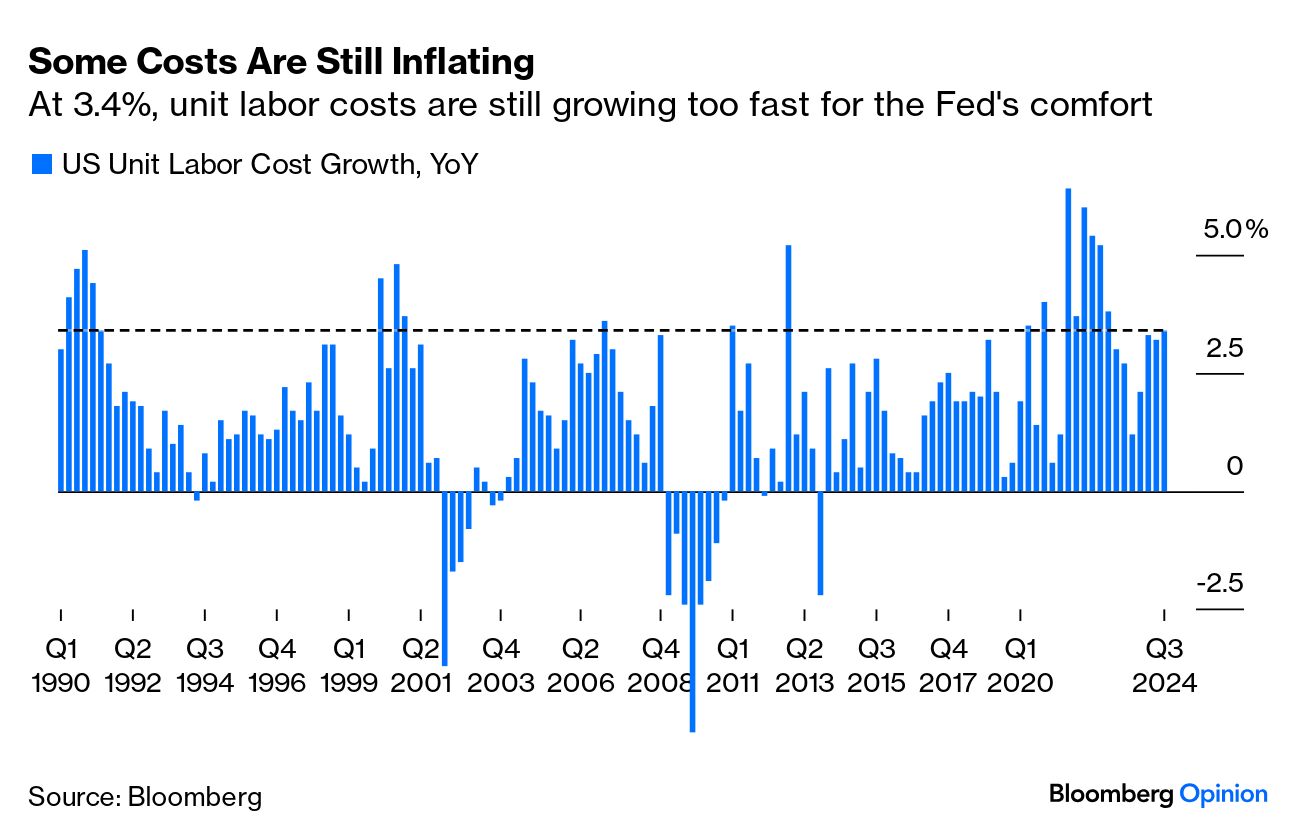

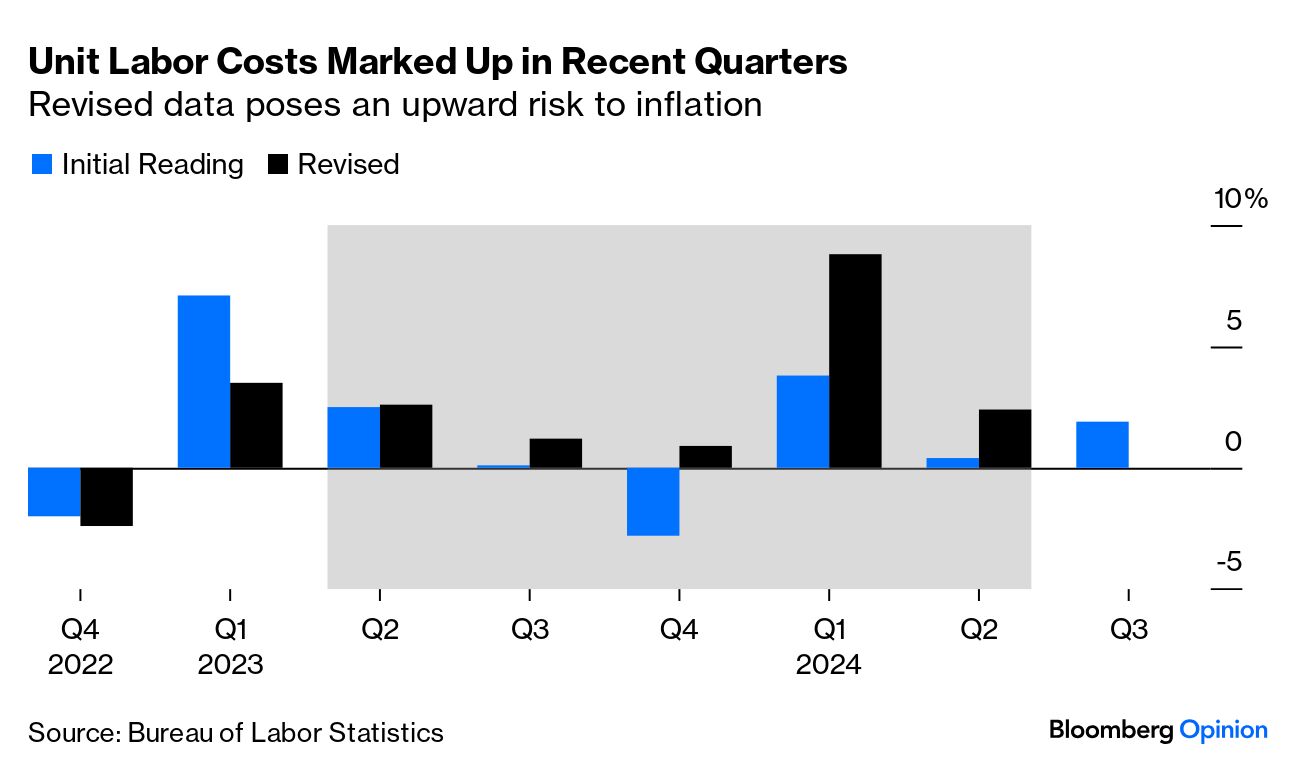

| Some analogies never stop giving. Points of Return has long compared the descent from high interest rates to a group of mountaineers climbing down a cliff. They need to stay roped together for safety, and risks are greater when descending. And just as that seemed to be going well, they have a new problem — there's a large and angry orange-skinned yeti waiting for them. Donald Trump won't return to the White House for another 10 weeks, but he's already casting a shadow over central banks. And his presence provided more or less the only note of interest after a Federal Open Market Committee meeting that felt like a total anticlimax after this week's political drama. The fed funds rate came down by 0.25% as universally expected, but the bottom line is that the expected course of rates over the next year barely moved at all. This chart shows implicit fed funds as they were at the end of last week, compared with the latest close after the FOMC and the election:  There were some minor tweaks of the communique, but nothing of any great importance. This was not a meeting when the committee publishes a new dot-plot of economic forecasts. At Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell's subsequent press conference, his comments arguably made it a little easier not to go through with a cut at next month's meeting as is generally expected (fed fund futures see a cut as a 71% probability), but there are two more inflation reports between now and then that will take prime importance. With no great shift from Powell, the equity market continued on its post-Trump rally to new highs, while bond yields reversed much of their move higher since the election.  The post-meeting fall in bond yields shows that there were at least some fears that the Fed would be more hawkish, thanks to the election result. With Trump 2.0 expected to boost growth and risk returning inflation, there was (reasonable) speculation that the Fed might not cut rates after all, or at least hint heavily that it would pause at next month's meeting. Significantly, SMBC Nikko's chief US economist Joe Lavorgna advocated a rate pause. As he served in the first Trump White House, this might be some indication of where the new administration's thinking could lead. He argued that data on labor costs are ambiguous enough to suggest that more rate cuts would be a risk. Thursday brought new unit labor cost growth data, and revealed that inflation in employment costs is rising again: Further, revisions to prior data suggested that labor costs had been rising faster than previously thought. That should be good news for the strength of the economy and living standards, but suggests inflationary pressure is still around. That's illustrated in this chart, put together by Bloomberg colleague Molly Smith: To quote Lavorgna: Data for the third quarter show a 3.4% increase from four quarters earlier, the biggest year-over-year gain since Q4 2022 (3.8%). The growth in labor costs is up sharply from where they were at this point last year (1.1%)… Would not a more prudent course of action be to wait and see how the labor market evolves following the hurricanes and settled Boeing worker strike? What would be the harm in waiting until next month's meeting when monetary policymakers receive cleaner data?

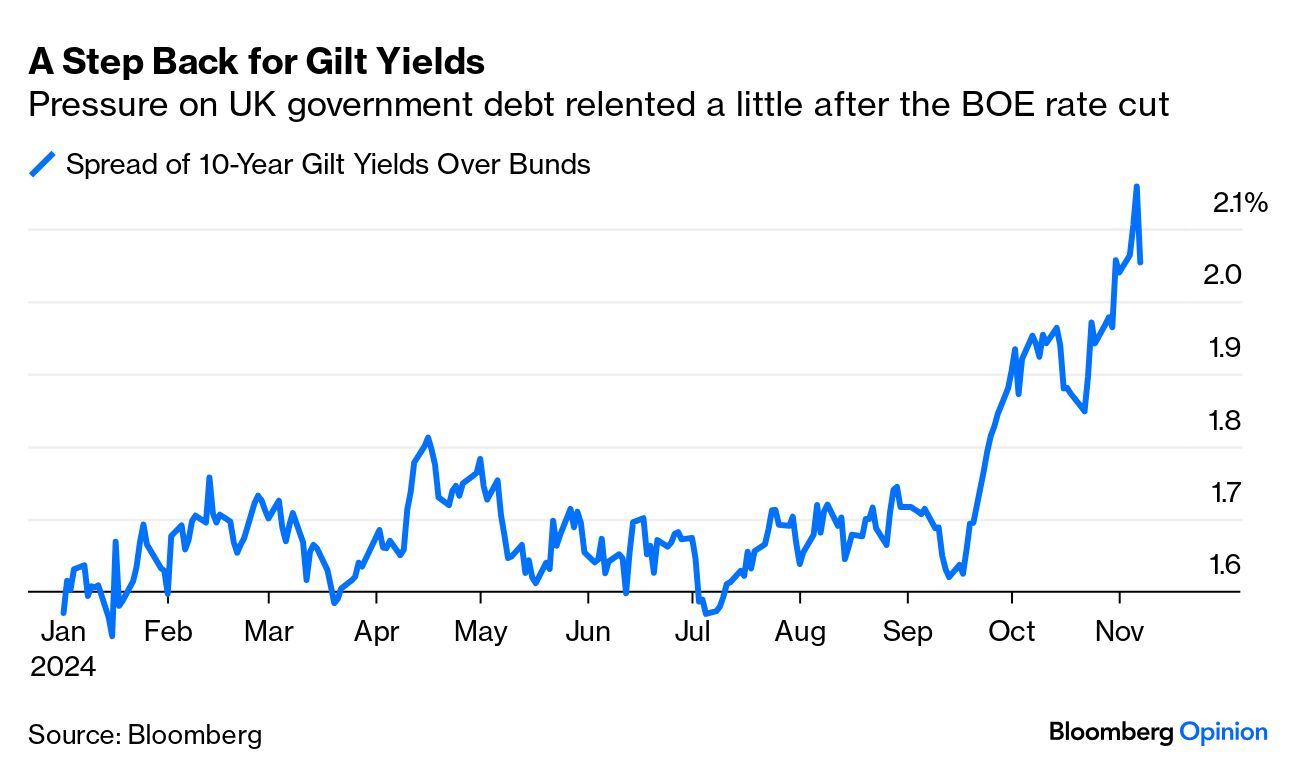

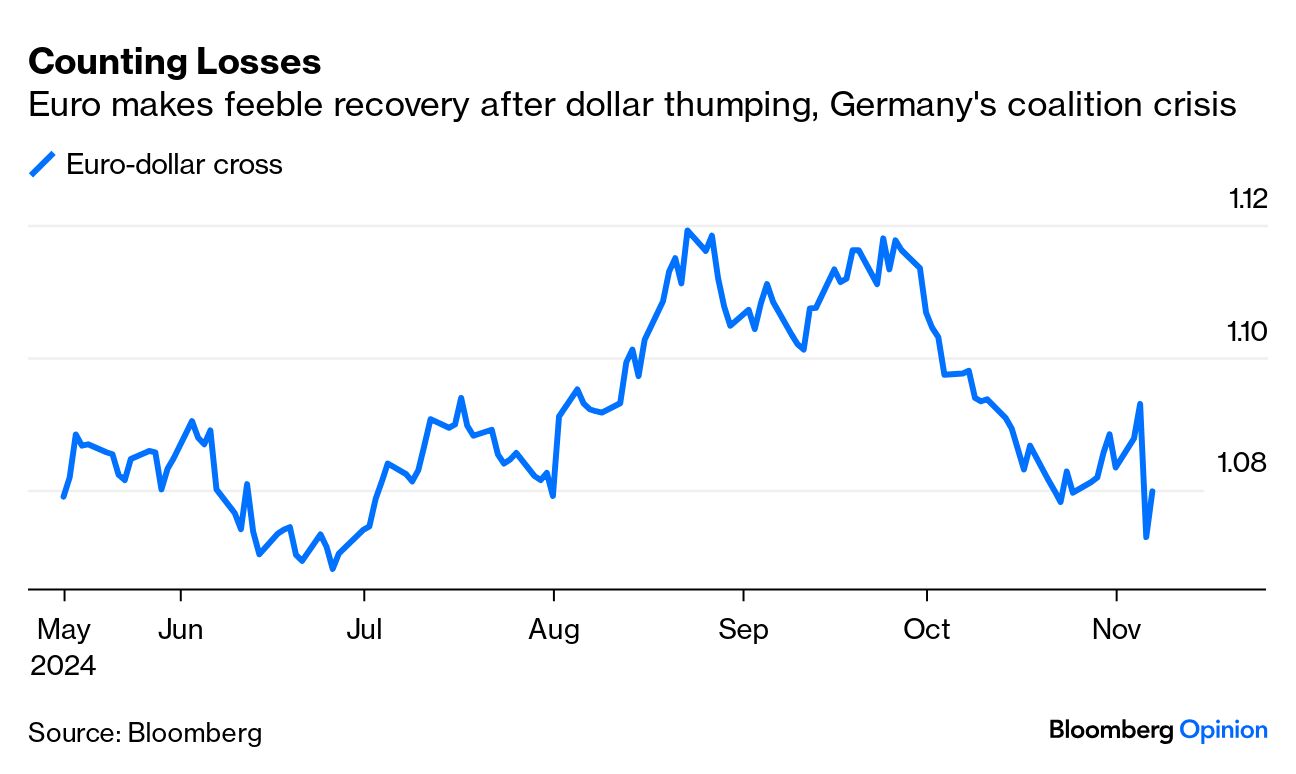

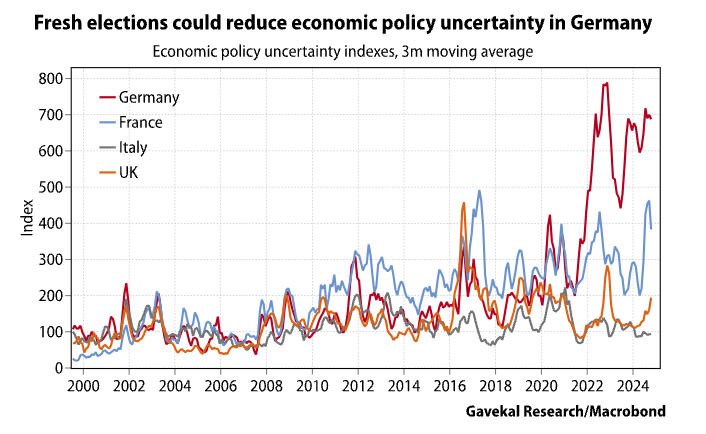

Those are sensible points from someone who might return to a position of some influence over the US economy. There is much greater tension over the fundamental issue of the Fed's independence, and whether Powell should resign now. When questioned if he would do so if asked, Powell responded with one word: "No." He added that demoting vice chairs of the committee was also "not permitted by law." It was plain that Powell, a lawyer, had prepared for the answer. He declined to make any comments on the election, and also refused invitations to estimate the effect that any Trump policies might have on inflation and unemployment.  What comes after 'no?' Source: 'Land of the Lost' (1976)/NBCUniversal/Getty Images There's nothing inevitable about a confrontation over the Fed, but the battle lines are being drawn. For the time being, markets were relieved that Powell was as dovish as he was, and this helped bring Treasury yields down. And in somewhat different cirucumstances, almost exactly the same thing happened in the UK, where the Bank of England also met amid sharply rising bond yields following a politically contentious event (the new Labour government's first budget, which includes several measures that will raise employment costs and hence inflation). Andrew Bailey, the BOE's governor, did a good job of saying that the budget measures might have an effect on inflation, but needn't affect planned rate cuts. As a result, the gilts market calmed — at least for the day. That shows in the spread of gilts over bund yields, which had risen sharply: The issue of bunds brings us to Germany. In soccer, Germany's national sport, the strategic use of player substitutions comes in handy, especially when your opponents vary their game plan and personnel. The urgency grows when trailing a superior opponent. Game theory principles in sport and politics aren't identical, but help illustrate the potential shift playing out in Berlin, where the spectacular collapse of Chancellor Olaf Scholz's three-year government will bring forward a scheduled election by at least six months. It began within hours of Trump's win, when Scholz fired Finance Minister Christian Lindner from an already fractious coalition government comprising his own Social Democratic Party, Lindner's Free Democrats, and the Greens (known as the traffic lights coalition for their party colors). The ouster came after disagreements over deficit financing and general economic policy direction. The stock market's warm reaction took some sting from the political crisis. The strength shown by the DAX index of German stocks relative to the Europe-wide STOXX index has been remarkable (although not surprising given France's problems): The euro, battered by a stronger dollar that heralded Trump's win, initially declined on the news but pared those losses: The market isn't oblivious to the risk involved in Scholz's move. Snap elections nearly 20 years ago burnt the SDP's fingers and ushered in Angela Merkel of the Christian Democrats as chancellor in a reign that lasted 16 years. But the need to try charting a "new" course for the struggling economy is unmistakable. Gavekal Research's Cedric Gemehl suggests there's a silver lining: Germany is set for a period of political uncertainty, which could be seen as bad news. Another way of looking at things is that paralysis within the governing coalition has meant elevated policy uncertainty when compared to German norms and with other big European economies. Hence, Germany may now be forced to tackle problems that have been allowed to fester.

This Gavekal chart stacks Germany's economic policy uncertainty against peers, and shows politicians need to sort out a common policy: An immediate easing of fiscal policy following the finance minister's departure is unlikely. Capital Economics' Franziska Palmas and Andrew Kenningham suggest that the budget for 2025 is unlikely to be passed before the end-2024 deadline and will probably be agreed upon once the new government is formed. At best, an interim budget regime caps monthly expenditure at 1/12th of spending in the previous year. Trump's proposed tariffs would complicate Germany's economic recovery efforts, but needn't be insurmountable. Gemehl believes the process could force German politicians and voters to make an uncomfortable reassessment of their political priorities and collective preferences: Talk is cheap and it remains to be seen if Germany will truly junk totems that act as self-imposed constraints on its economy. Still, while a stagnant status quo remains the path of least political resistance, there is a rising chance that Germany embraces a revival approach rather than doubling down on cost-cutting, which in today's world can only end with economic suicide.

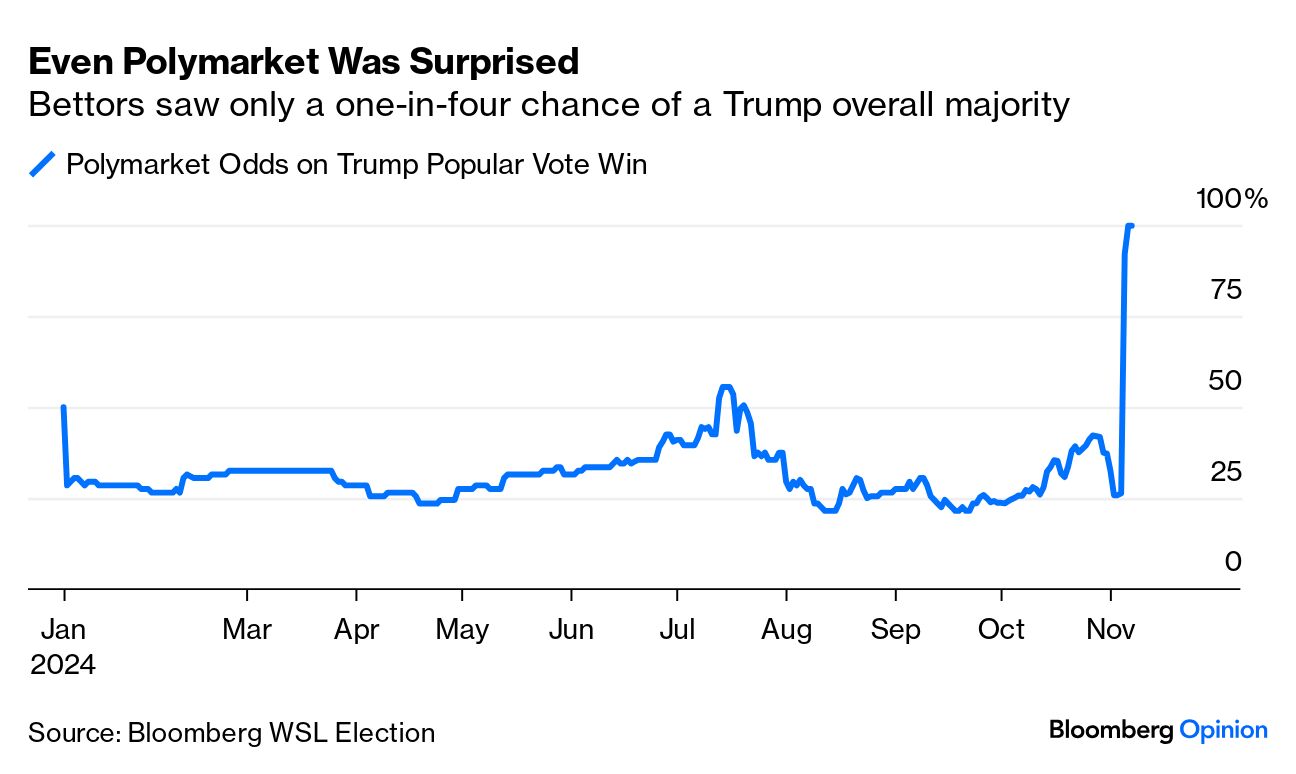

TS Lombard's Davide Oneglia suggests that Trump's election and the sense of urgency inspired by a crisis could finally force Germany and the rest of the EU to coordinate fiscal policy and structural reforms (Mario Draghi gave them a blueprint two months ago). Otherwise, complacency in Brussels and Berlin about the dangers posed by a "Trump shock" in trade and security policy could exacerbate market reactions if risks materialize.  This isn't Merkel's Germany. Photographer: Krisztian Bocsi/Bloomberg The first Trump presidency happened during Merkel's reign, when she offered stability both to Germany and the EU. This Germany is a pale shadow of that era. There doesn't appear to be another Merkel on the scene, but drastic action by the current government to create a stronger, more united front makes absolute sense. That explains why markets seem to think this snap election — unlike those earlier this year in France and the UK — is a risk worth taking. —Richard Abbey The prediction market saga of the last month was entertaining. The battle between those who find the whole notion of political gambling reprehensible and those who see this phenomenon as a way to bring market discipline to electoral forecasting will continue. The two established prediction markets that offered odds throughout the year are PredictIt, an onshore non-profit with strict limits on positions, and Polymarket, which is based offshore and has far more liquidity. Both saw the election much the same way. Polymarket was (correctly as it turns out) more bullish on Trump, but neither put his odds as high as 60% entering Election Day. Given how clear his ultimate victory was, that doesn't seem to show any great and brilliant foreknowledge: Prediction markets seem to have been as surprised as everyone else by Trump's victory in the popular vote. Polymarket bettors briefly thought his chances of this were better than 50% in the wake of the July assassination attempt, but by Election Day it had declined to 25%: Meanwhile, most of the polling industry can be relieved that they came much closer to getting the result right this time, although a shift toward Kamala Harris in the last week adulterated their record somewhat. There will be much more to say in due course, and Matt Levine has already weighed in. But it's fair to say that the debate remains incomplete. Mountaineering never ceases to enthrall. For good movie-watching, try Touching the Void, the true story of what happened after one climber was forced to cut the rope binding him to his injured partner, or the Oscar-winning documentary Free Solo, about scaling El Capitan in Yosemite. We can be thankful that the monetary descent is going better than the tragic 2008 descent of K2, documented by Graham Bowley in the gripping No Way Down. And for some hints on how Tom Cruise climbed a peak in Utah in one of the Mission Impossible movies, watch this. And however you feel about the election in the US, try to have a good weekend everyone. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: - Juan Pablo Spinetto: Sheinbaum Needs to Prepare Mexico for Trump 2.0

- Parmy Olson: Does Nvidia's CEO Dream of Electric Androids?

- Matthew Brooker: Rebuilding Britain Is More Than a Sugar Rush

Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment