| Politicians shouldn't judge themselves by the stock market. But it's happening again. Here follow some cautionary tales on what the post-election rally in stocks does and does not portend for the US economy over the next four years. Scott Bessent, for many years a leading investor for George Soros, may very well be the next Treasury secretary. The Polymarket prediction market (which hasn't gone away) puts his chances at 70%. In an important op-ed for the Wall Street Journal, he has set out an agenda for economic policy that's worth reading. Headed "Markets Hail Trump's Economics," it makes this claim: Asset prices are fickle, and long-term economic performance is the ultimate measuring stick. But recent days prove markets' unambiguous embrace of the Trump 2.0 economic vision. Markets are signaling expectations of higher growth, lower volatility and inflation, and a revitalized economy for all Americans.

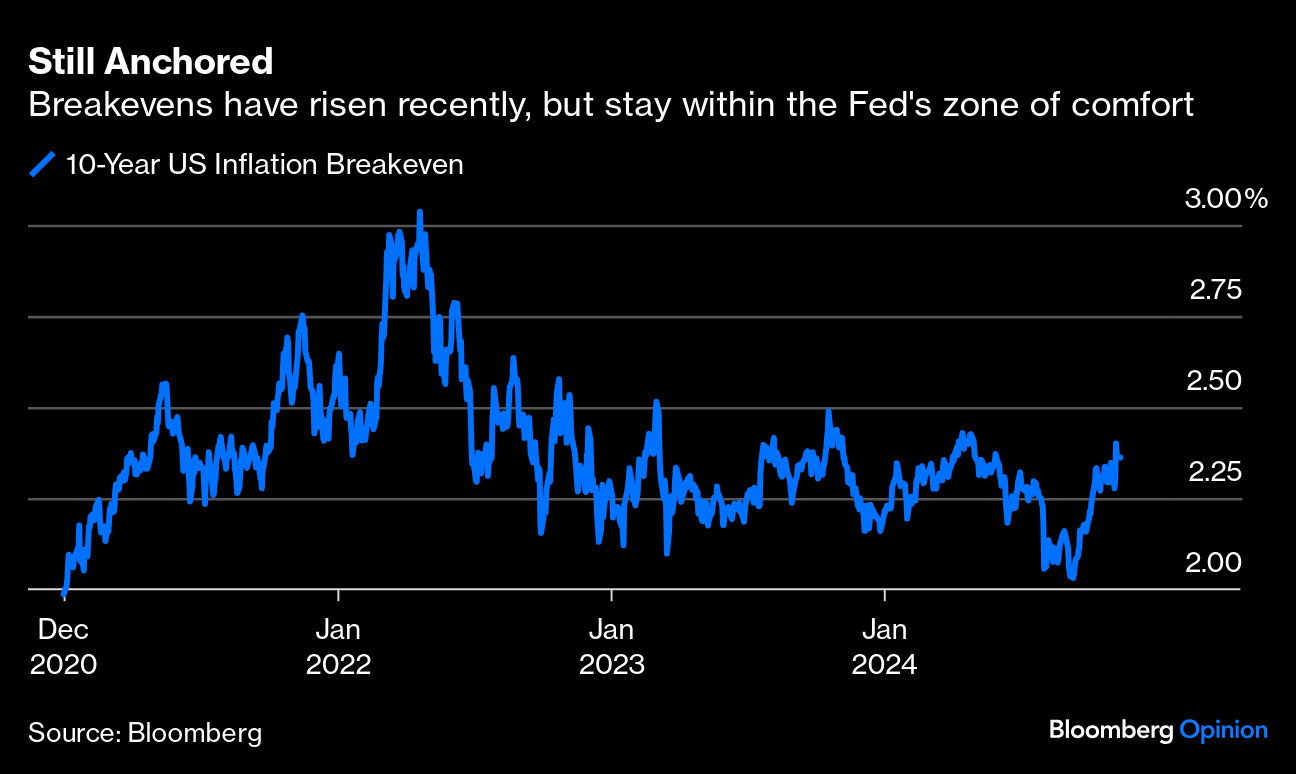

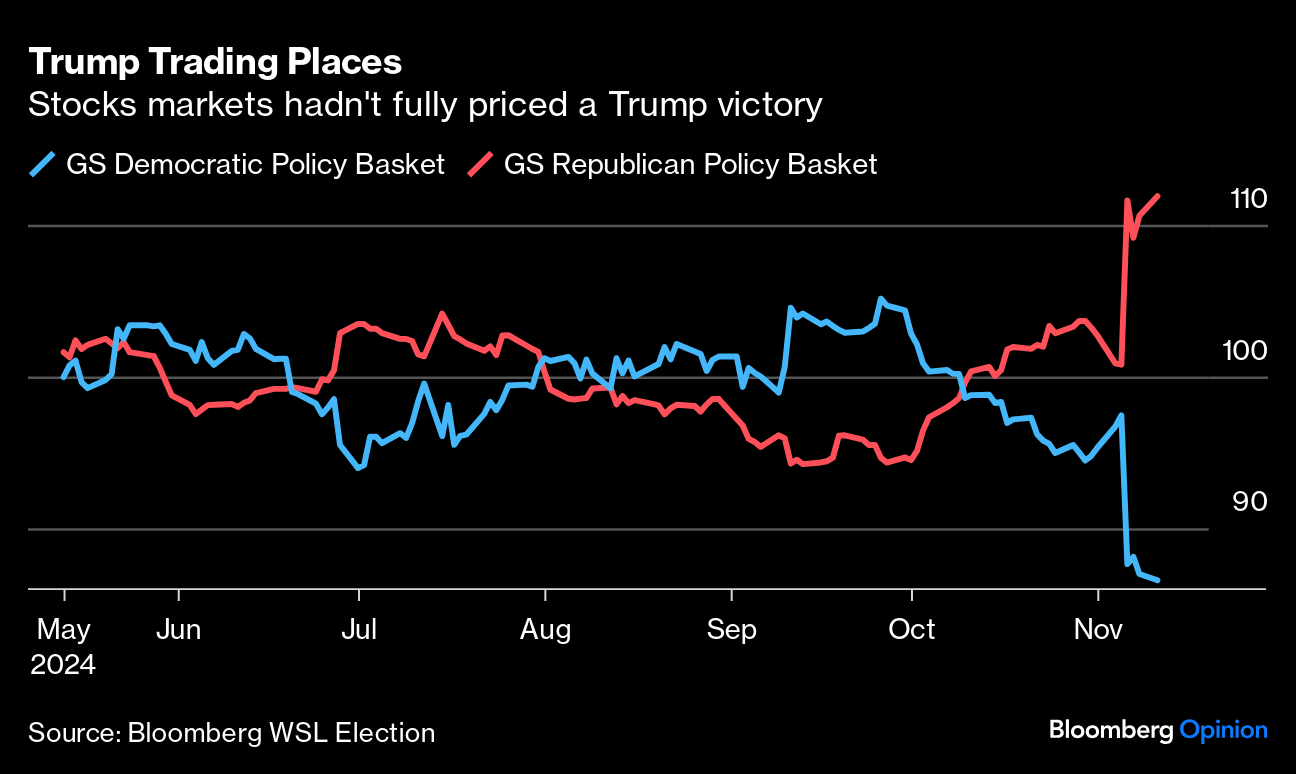

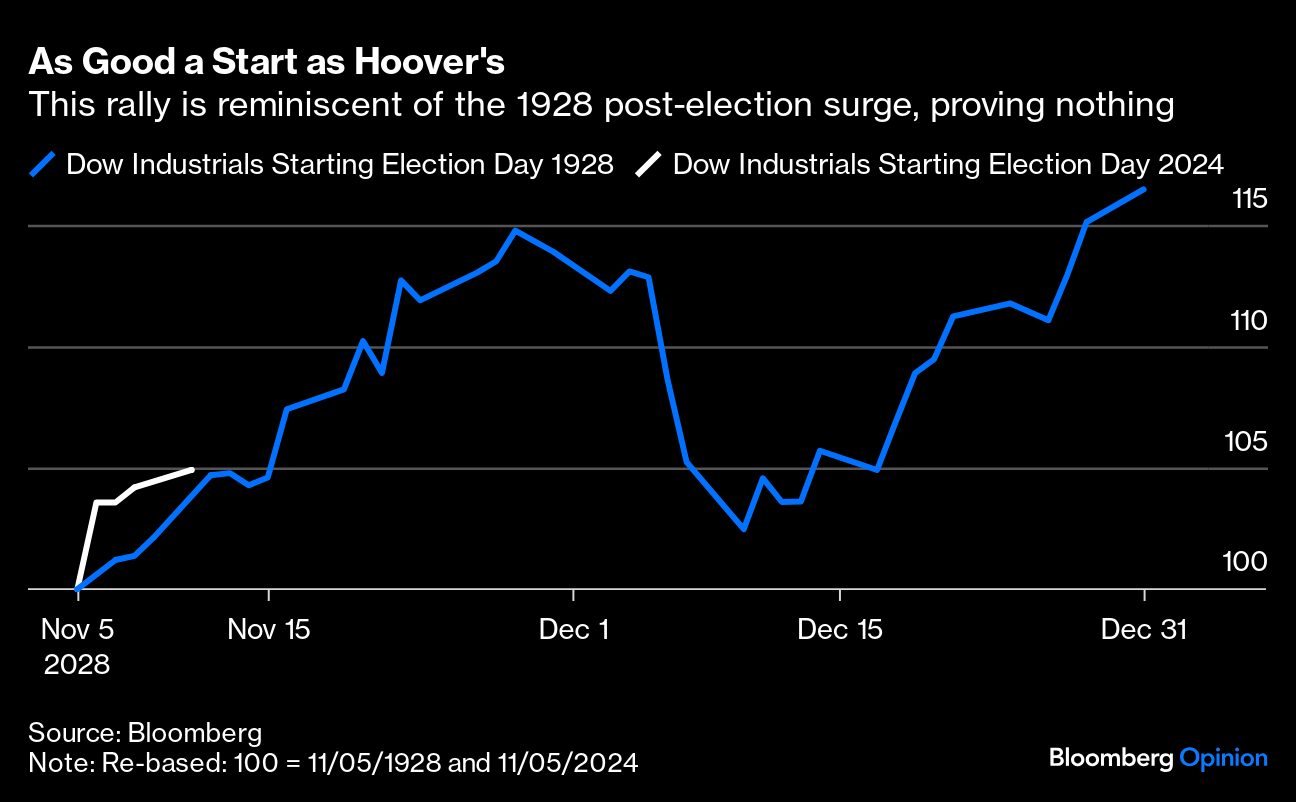

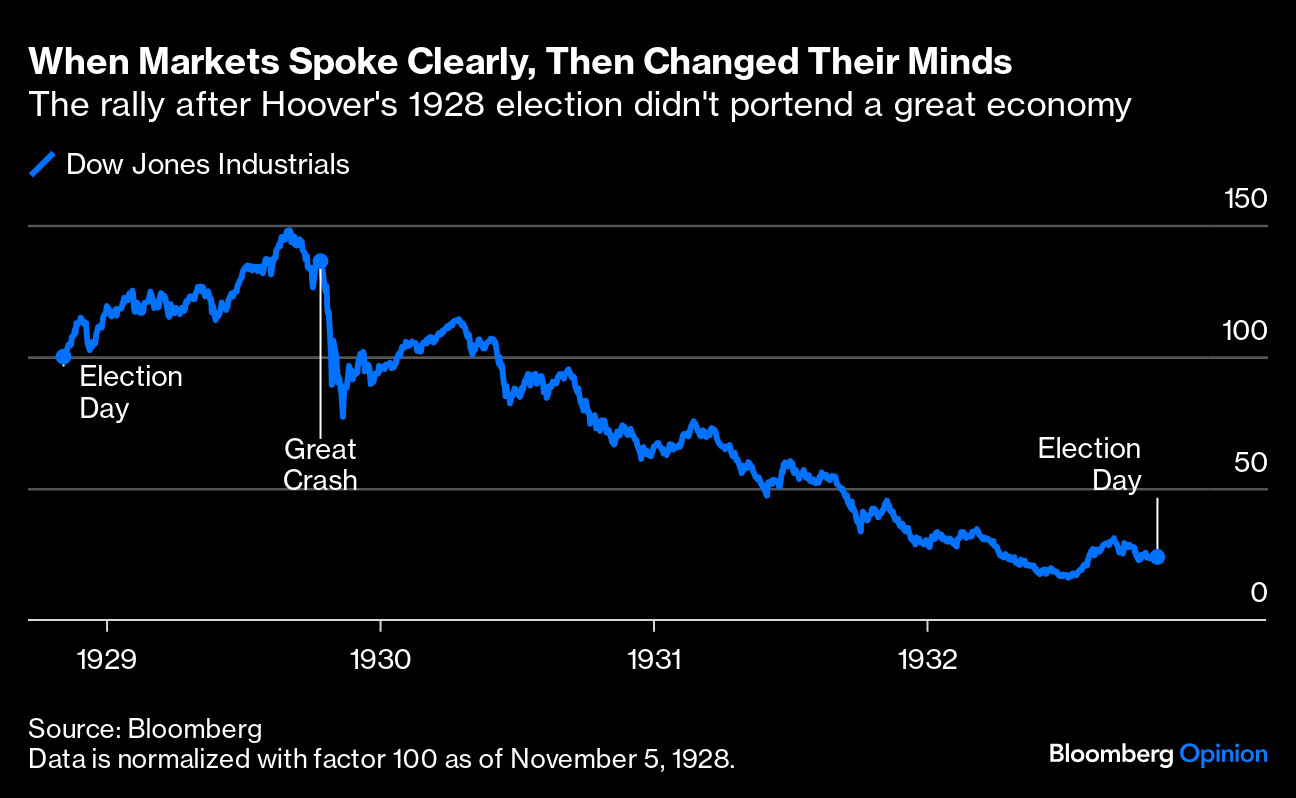

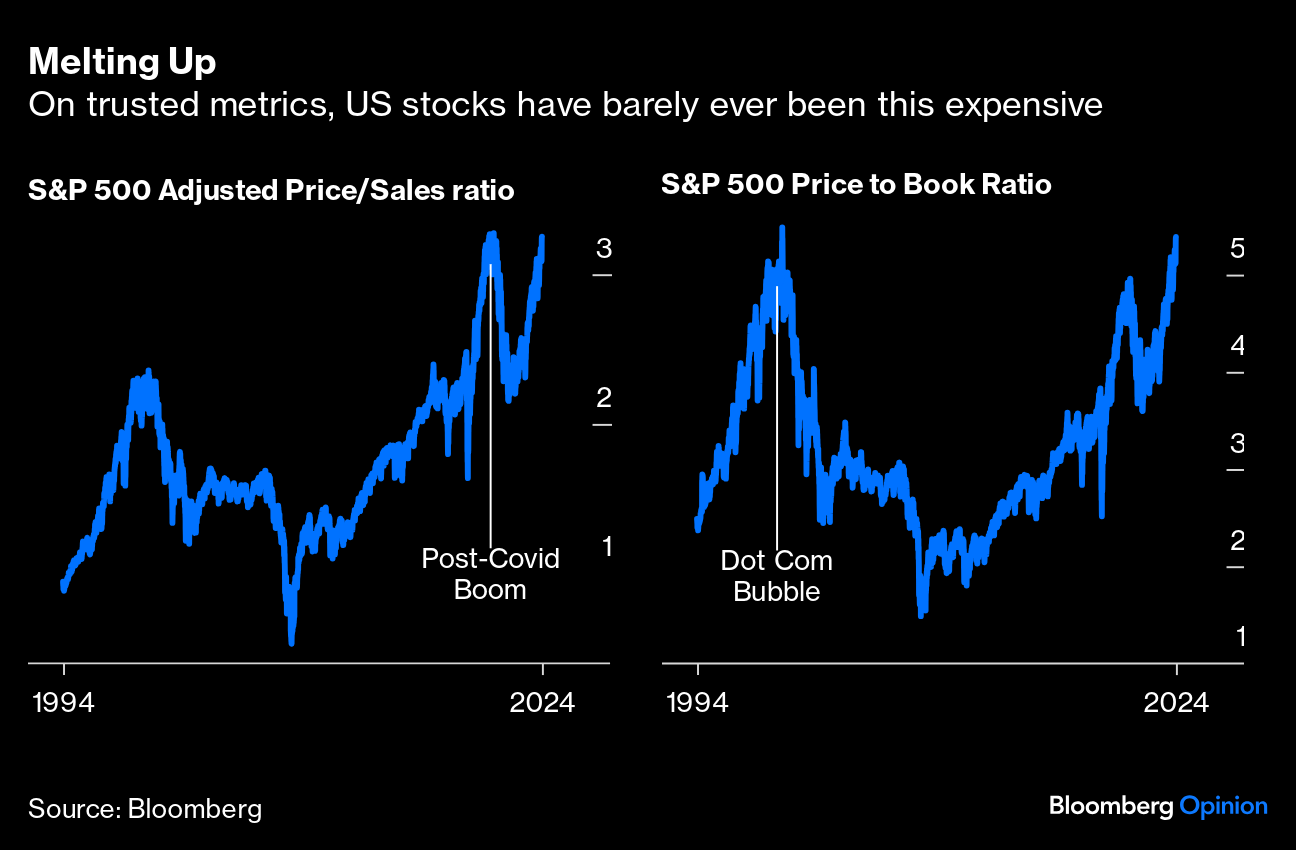

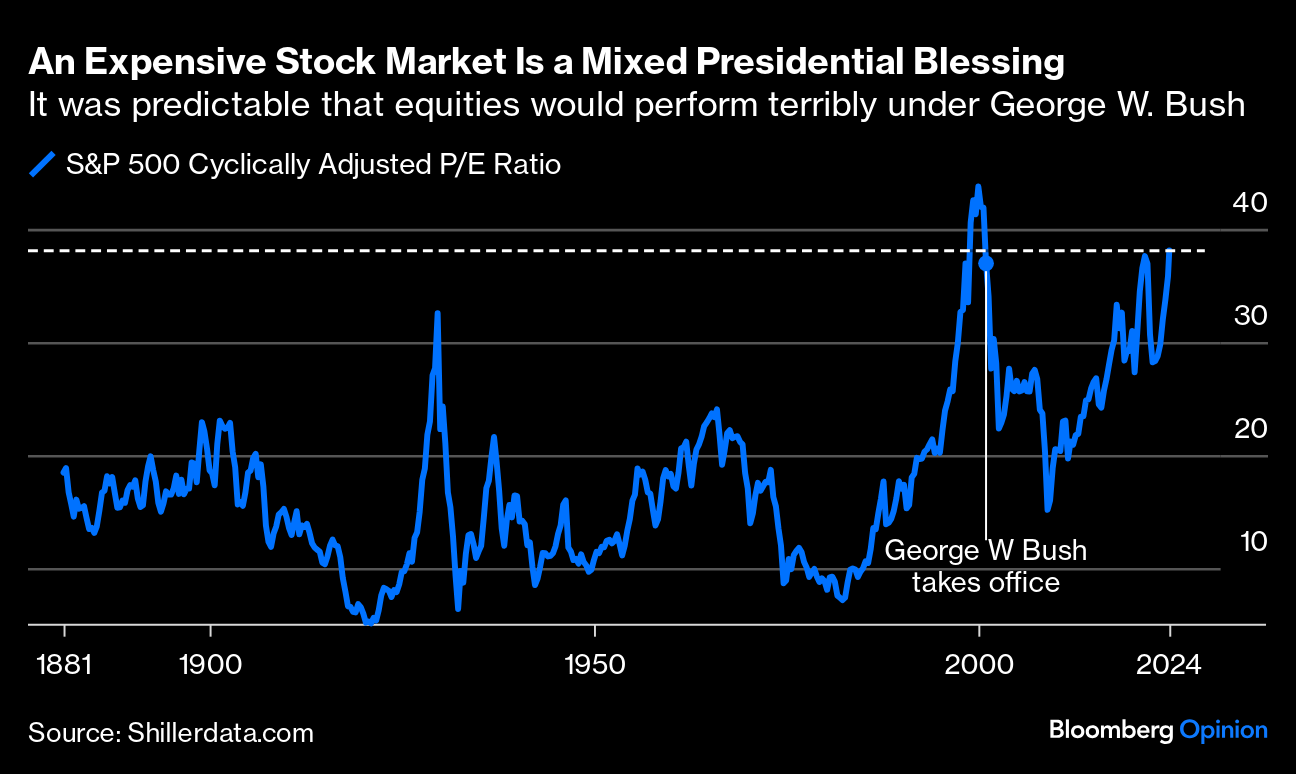

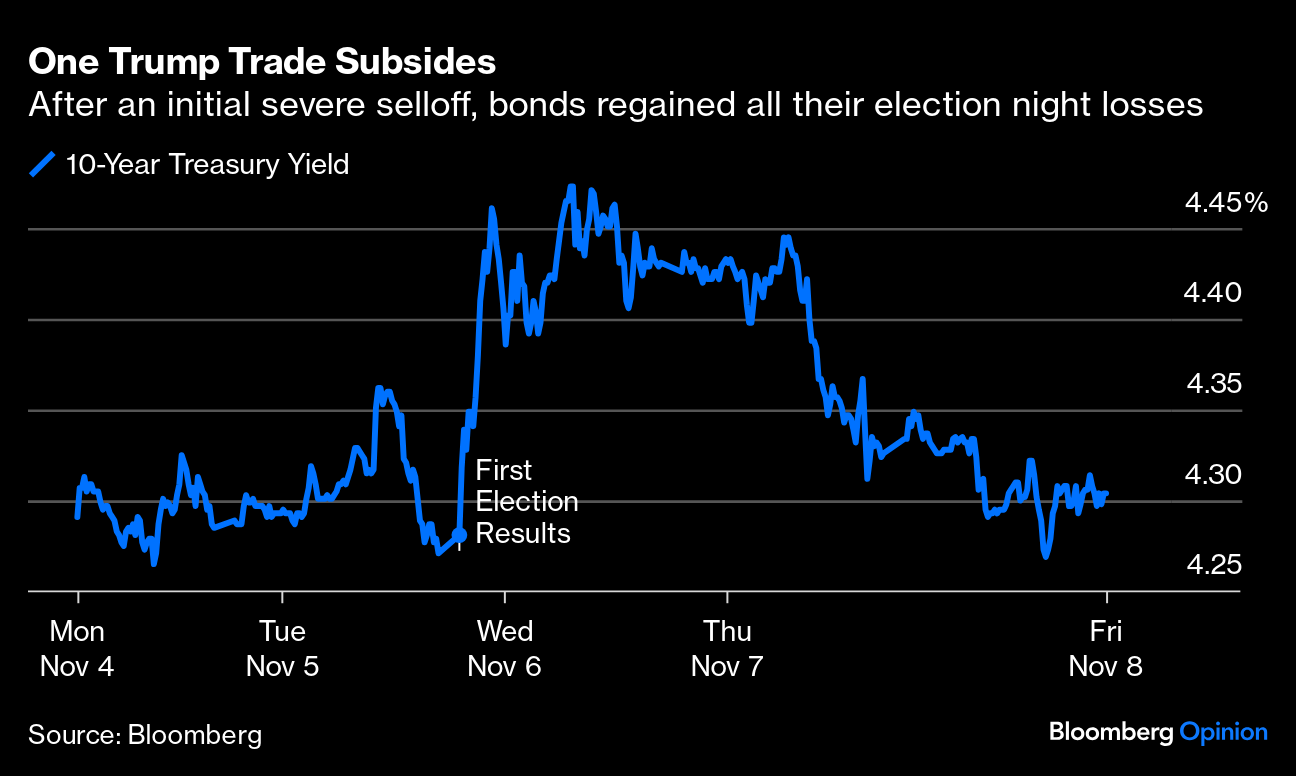

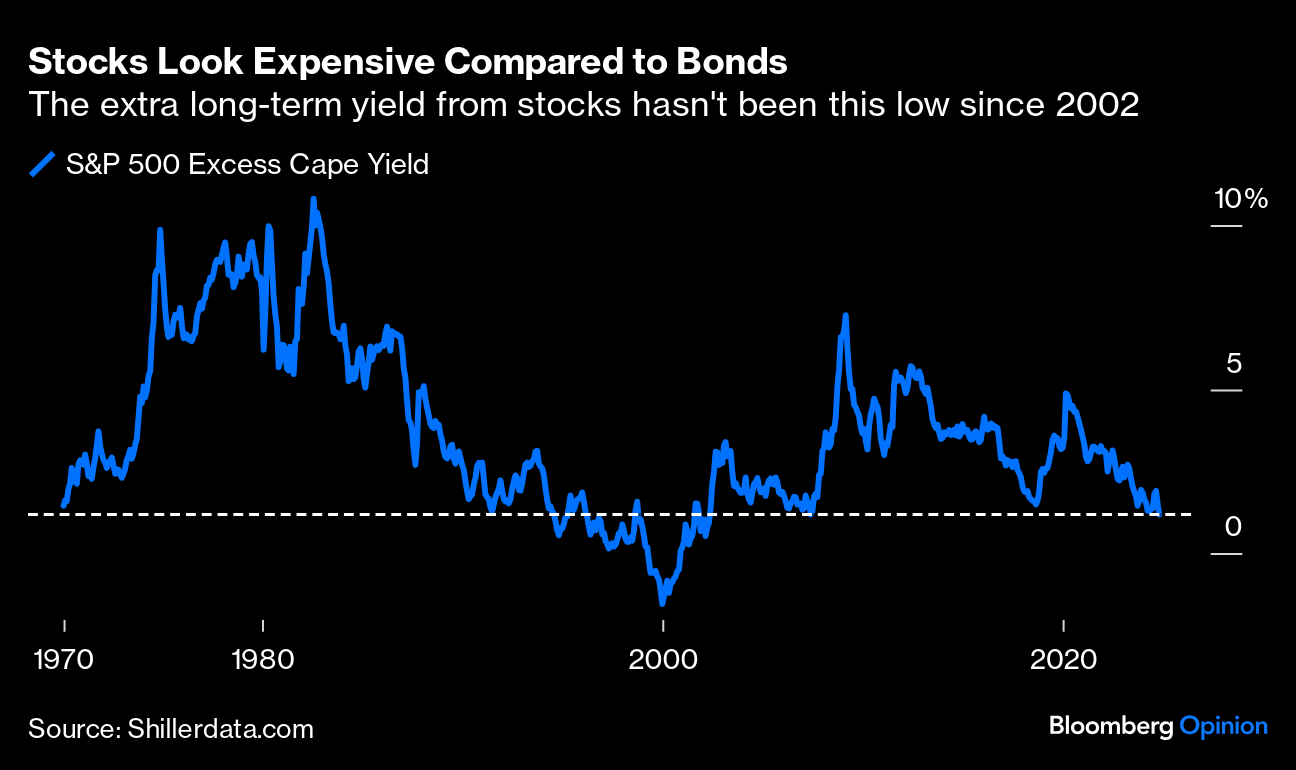

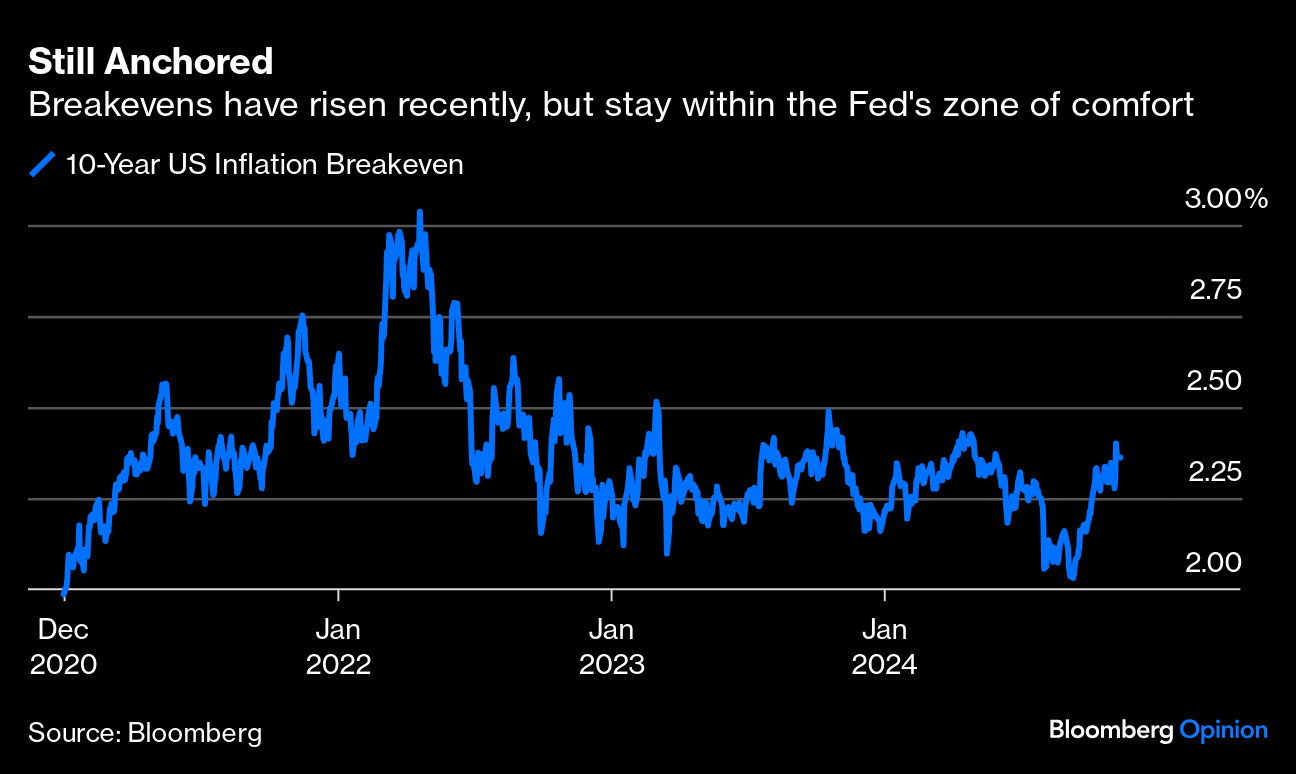

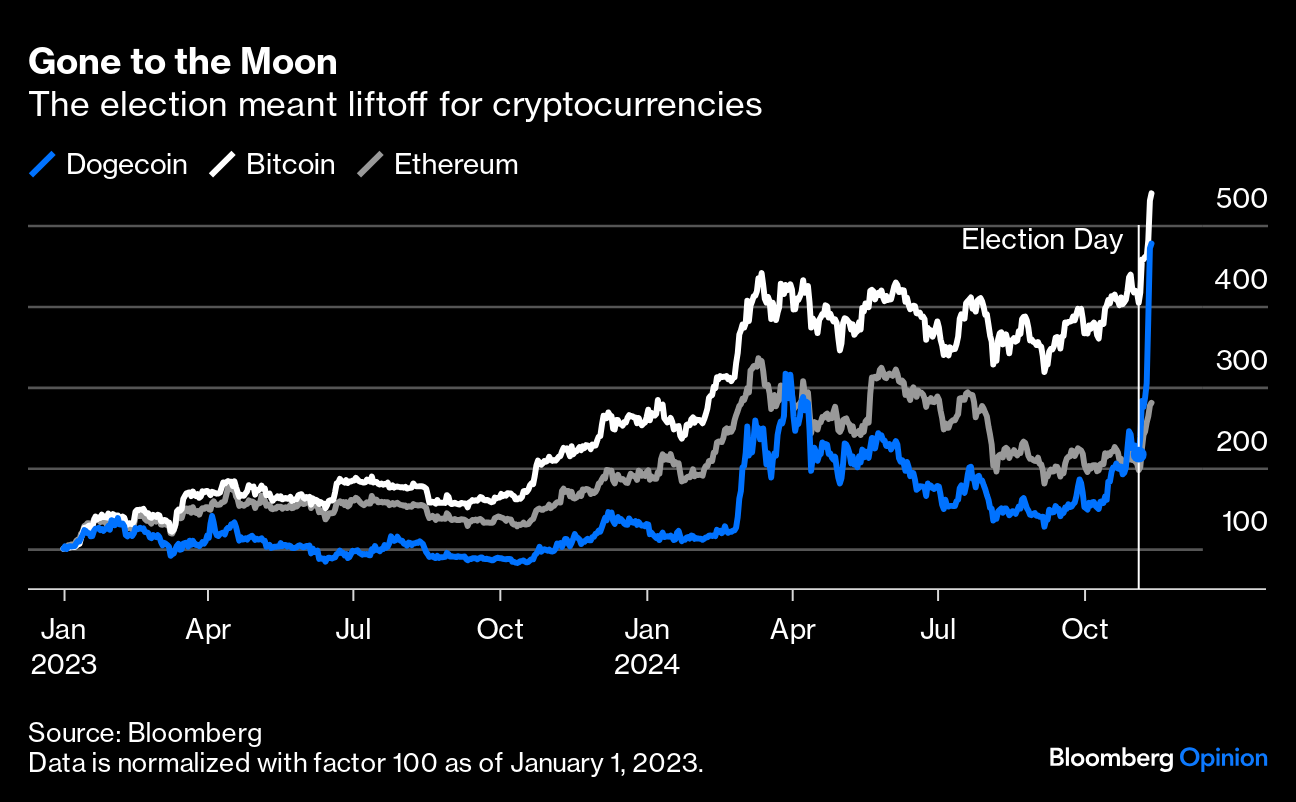

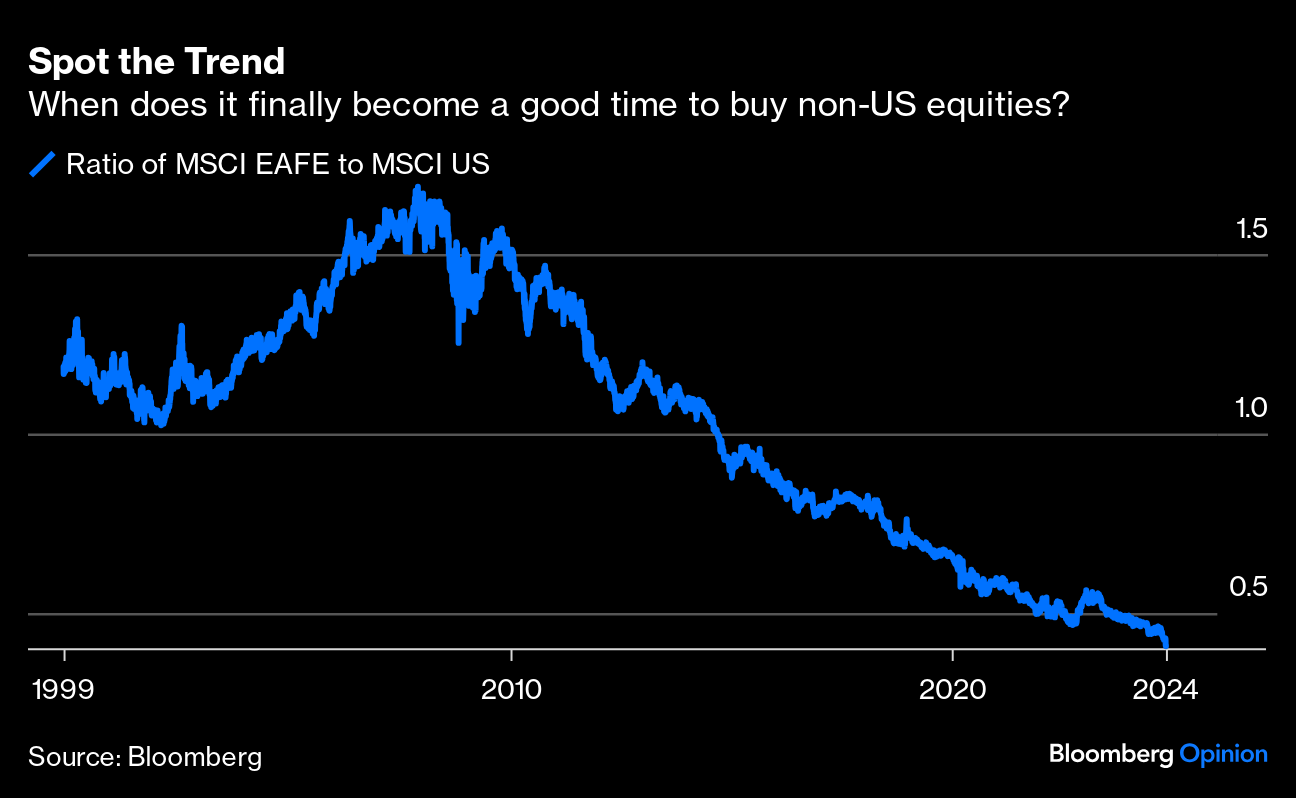

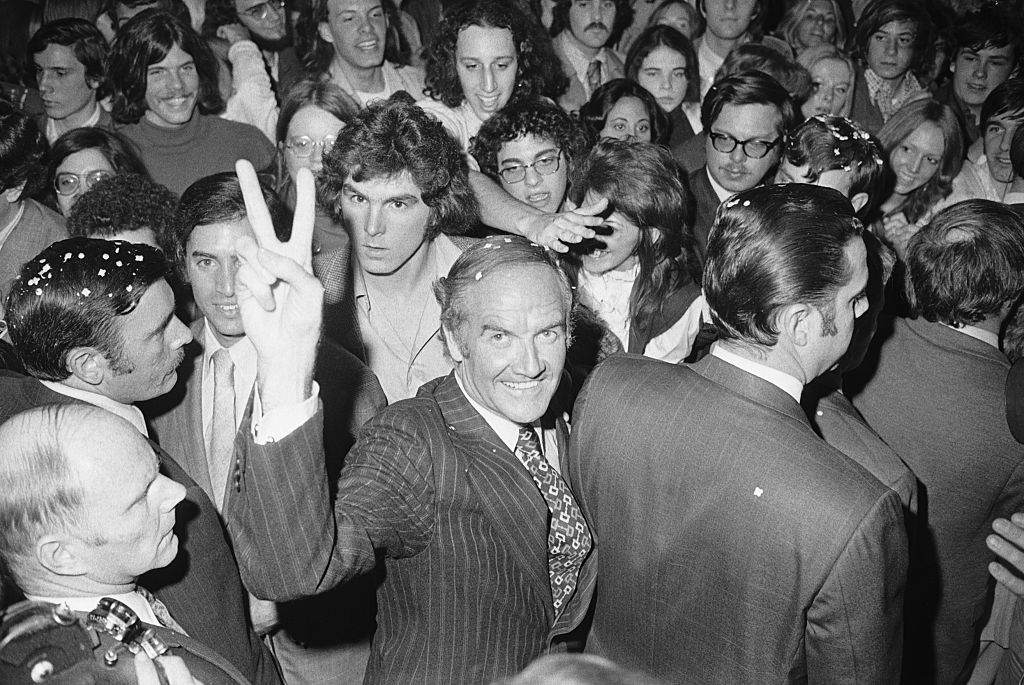

It's necessary to be careful with this. Asset prices are indeed so fickle that it's unwise to draw too many conclusions just yet even from the emphatic rally that has followed the election. It's certainly true that the stocks thought most likely to benefit from a Trump administration, rather than from a Democratic alternative, have enjoyed quite a rally, and shown that the victory was not priced in before Election Day: In the following chart, I have compared the Dow Industrials' performance from Election Day in 1928, when Herbert Hoover was chosen president, to its performance since a week ago. They're very similar: Does this prove that Donald Trump's second term will pan out like Hoover's? Of course it doesn't. And that's just as well, as this is what happened to the Dow in the four years between Hoover's election and his landslide defeat to FDR in 1932: Again, to be clear, a primitive overlay chart is no kind of evidence that the stock market is destined for a crash like 1929. The point is that the post-election rally doesn't prove anything either way. What predictions can we more safely make? Generally, the single most important factor in the long-term performance of an investment is the price at which you bought it. If it was too expensive, you're much less likely to do well out of it. This is how two of the most simple valuation metrics for the S&P 500 — its ratio to sales and its ratio to book value — have moved over the last 30 years. On the former, the market is very close to the record set in the the post-Covid boom in 2021. On the latter, it's almost taken out the all-time high from the dot-com bubble in 2000: Nothing proves that the stock market is about to fall as it did on those two occasions. But the higher the valuation, the higher the odds against continued strong performance. In general, it would be unwise for any politician to seek to be judged by share prices at present, as it involves setting a target on their back. Using a subtler metric, Robert Shiller's CAPE (cyclically adjusted price/earnings) multiple aims to correct for the market's moves within the economic cycle by comparing share prices to average inflation-adjusted earnings over the previous decade. Shiller has calculated the ratio back to 1881, and the following chart is taken from his website. On this basis, only one presidential election has previously taken place with the stock market so expensive, in 2000, when George W. Bush emerged victorious. The CAPE is calculated monthly. On Nov. 1, 2000, it was 38.78; on the first of this month, it stood at 38.11: With this post-election rally, the CAPE is now higher than when Bush took office in 2001, amid the fallout from the dot-com implosion. It's possible that Trump 2.0 will unleash a new paradigm for stock investing and take valuations to previously unimagined heights. It's more likely that performance won't be great, for reasons that have nothing to do with his economic policies. Beyond stocks, other post-election Trump Trades also urge caution. The spread of high-yield bonds' yields over Treasuries, a crucial measure of the compensation you receive for lending to companies with weak credit, has dropped to a 17-year low in recent days, according to Bloomberg indices. The spread was only tighter for a matter of days in the summer of 2007. On that occasion, spreads rose quickly as the structured credit market based on subprime mortgages began the collapse that ended with the Global Financial Crisis: Again, this absolutely doesn't prove, or even suggest, that we're about to stage a repeat of the GFC. It does, however, strongly indicate that markets are very ungenerously priced for anyone who wants to enter. Any worsening of credit conditions, starting from these highs, would hurt. It might be wise for incoming politicians to talk down the significance of the stock market, emphasize that it looks expensive, and seek to be judged by more or less any other metric. There is one important market, however, where the immediate post-election Trump Trade has reversed, and this is healthy. Treasury bond yields surged higher as the results came in, signaling alarm that tax cuts and tariffs would mean inflation and higher rates from the Federal Reserve. But after surging some 20 basis points in a matter of hours, the bond market (closed Monday for Veterans Day) calmed down swiftly. By the close on Friday, it had completed a round trip: It might make sense for the Trump team to treat this as a meaningful shot across its bow, but also take some comfort that there wasn't appetite to keep yields that high. Even back at 4.3%, the 10-year yield makes it somewhat harder to justify current stock market valuations. Another chart from Shiller's website shows the extra cyclically adjusted yield paid by stocks compared to long-term bond yields. The lower the excess yield, the less attractive stocks look compared to bonds: One critical component of bond yields is the policy rate set by the central bank. At the beginning of October, the fed funds futures seemed convinced that policy rates would fall below 3% by January 2026. Now, that figure is close to 4%. The shift in rate-cut expectations as confidence took hold that Trump would return to the White House has been something to behold:  This is good for the Trump administration in that the Fed has less need to cut rates if the economy is growing, so it does show some confidence in growth. But it also suggests that price rises will make it harder to cut. Conventional wisdom has already coalesced on the notion that the Democrats' defeat was chiefly attributable to their failure to stop the inflation spike. It's politically imperative to avoid another one. On this front, the bond market is less emphatic. Two months ago, the 10-year inflation breakeven, its implicit forecast of average inflation for the next 10 years, came close to 2.0%, the Fed's target. In the aftermath of the election, it touched 2.4%. The good news is that it has ticked back a little from there, and remains lower than for much of the last two years:  There's no great reason for alarm in the bond market. The vigilantes are keeping a watching brief for now. But the markets are not signaling confidence in lower inflation, while fed funds expectations make it harder for stocks to keep rallying. All of this said, when markets develop momentum, it's dangerous to get in their way. The crypto market shows clear evidence of frothy excess, but it also shows very strong confidence that will be difficult to dislodge: And trends, once established, are difficult to change. For the most spectacular example, this is how the MSCI EAFE index (for Europe, Australasia and the Far East, effectively the non-US developed markets) has performed relative to the US over the last 25 years. EAFE has dropped in absolute terms since the election (so a Trump victory isn't being hailed as a positive development outside the US). Unlike America, stocks in these countries almost all look quite cheap on metrics such as the CAPE. But who is going to have the courage to get in the way of a trend like this one? In conclusion: Yes, the markets have had a positive response to the election. The calmness of bond yields is actually more important and reassuring than the rally in stocks. And with stocks looking exceptionally expensive, it's very, very unwise for any politician to ask to be judged by them. There was an election in the US last week. You probably read about it. You won't need to read yet more opining on this subject, but with luck these three thoughts might be helpful: First, it's silly to say that the Biden administration should have done more to help working-class Americans. More or less everything his administration did was aimed at precisely those people, including massive job-creating infrastructure investment, lots of aid to tide through the later stages of the pandemic, releasing oil from the strategic reserve to bring gas prices down, and intensifying the tariffs on China. "Scranton Joe" was the embodiment of the strand of Democrats that hails the working man. The problems were 1) inflation, 2) the time it takes for the benefits of spending to show up, and 3) Biden's lost ability to communicate and sell what he was doing. But if Democrats think they can return to power by prioritizing the working class, they will quickly realize that they're proposing exactly what Biden has already done.  Men at work, circa 1950. Photographer: Ben McCall/FPG/Hulton Archive/Getty Images Second, there's no particular reason to think that the new Trump majority would be proof against another economic implosion. By the time the dust settles, it looks like Kamala Harris will have taken a little over 48% of the national vote. For comparison, John Kerry won 48.3% in 2004, and Michael Dukakis took 45.6% in 1988. Both times, Democrats won the next election, thanks to the economy. Going back further, George McGovern won only 37.5% in 1972, while Barry Goldwater got 38.5% in 1964; both times their party won the next election thanks to political chaos. Trump has a mandate to run the economy his way. If it works, the Republicans will stay in power, but if it doesn't, they probably won't.  McGovern's only electoral votes came from Massachusetts and DC. Source: Bettmann Archive/Getty Images And third, on the popular vote: The last week has seen more or less universal acknowledgement that Trump's popular majority really matters. It plainly confers greatly more legitimacy than the technicality of a win in the Electoral College eked out despite a loss of the popular vote. This time, he won it fair and square and opponents' response has been very different as a result. Moreover, the Electoral College just isn't fair. I cast my first vote as an American citizen last week, but as I cast it in true-blue New York, it didn't really matter. Why should my vote, or that of the good citizens of solid red states like Alabama and Wyoming, count less than those of Pennsylvanians? It won't happen, but this would be a good time to amend the Constitution and abolish the Electoral College.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: - Marcus Ashworth: The Mighty German Bund Is Losing Its Benchmark Shine

- David Fickling: China's Energy Dominance Gets a Boost From Trump

- Marc Champion: Trump Doesn't Have to Be Bad News for Ukraine

Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment