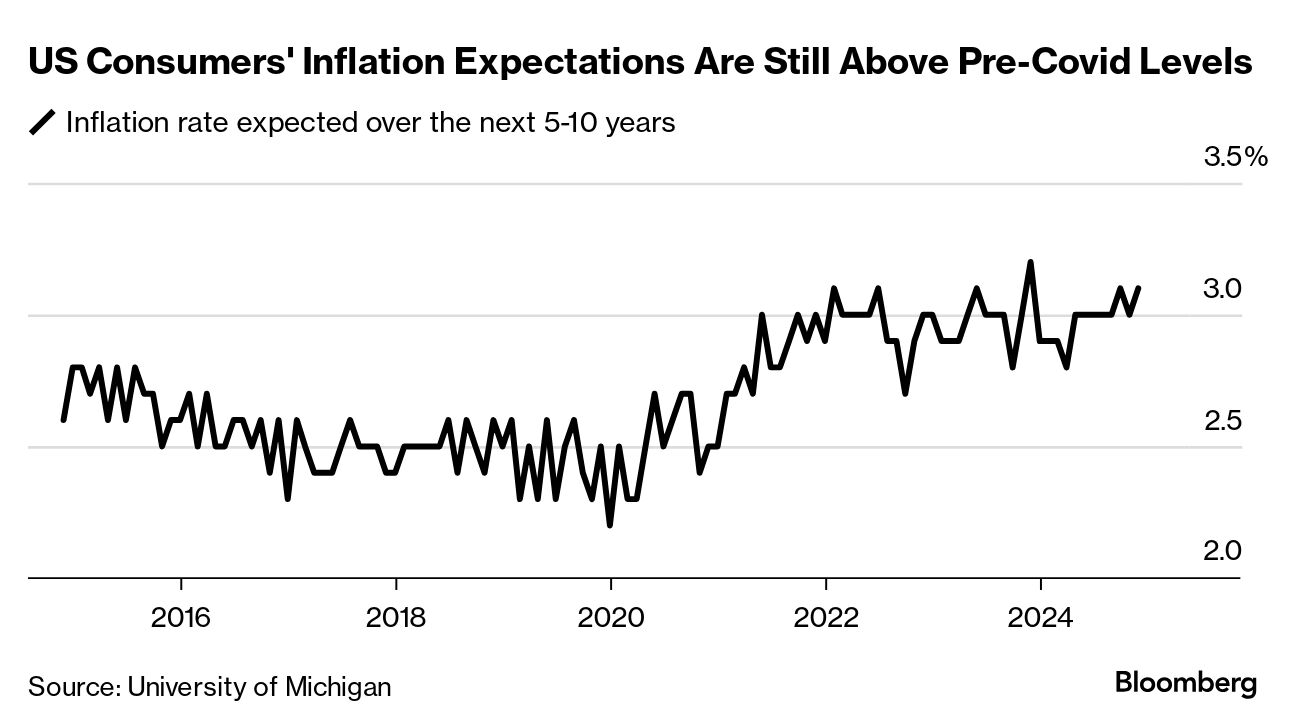

| Less than six months ago, leaders of the Group of Seven industrialized nations described the global economy as unexpectedly resilient. Voter support for six of those leaders has proven somewhat less so. Two have been ousted—Prime Ministers Rishi Sunak of the UK and Fumio Kishida of Japan—and voter disapproval of President Joe Biden helped doom his would-be successor. French President Emmanuel Macron's authority shrank after his snap election gambit failed and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz saw his coalition collapse just this week. Meanwhile in Canada, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau's poll ratings have hit a new low. Only Giorgia Meloni, the far-right prime minister of Italy, looks secure for now, with her anti-immigrant movement's preferred candidate winning a regional election last week. Even beyond the G-7, ruling parties from Portugal to the Netherlands have lost power. In sum, "the anti-incumbency trend in the world is real and very powerful," said Stephen Jen, chief executive of Eurizon SLJ Capital. So what are the economic implications? They tilt toward reflationary policies that stoke growth and incomes as politicians seek to pacify angry electorates looking for payback over post-Covid cost-of-living surges. The irony of course is that efforts to mollify them will likely reignite the very inflation they bemoan, while fostering tension between governments and central banks. For some monetary policymakers who only just had "soft landings" in sight, a fresh quandary may be looming over how to react to fiscal policy.  Followers of Donald Trump celebrate his election victory on Nov. 6 in Florida. Photographer: Eva Marie Uzcategui/Bloomberg Rob Subbaraman, head of global markets research at Nomura Holdings Inc., said central banks like the Federal Reserve will be "once bitten, twice shy," on any signs inflation is getting away from them again. Having forecast ahead of the US election that inflation would be 75 basis points higher if Donald Trump were to win, Nomura swiftly erased three of its four forecast interest-rate cuts for 2025 when result became clear. "The Fed is more sensitive to inflation risks now after being too slow to react last time," he said. "There's also a risk that inflation expectations could be dislodged more easily this time because workers and employers have already had to reset from the last inflation outbreak." Indeed, inflation expectations in the US haven't returned to pre-Covid levels, as the University of Michigan's latest survey showed Friday. Now those expectations may be challenged by steep tariff hikes, which Trump is promising once he's back in the White House. The Republican's plan to ask Congress to not only extend his 2017 tax-cut package, which largely benefitted corporations and the rich, but end levies on Social Security payments and on tipped income are also seen as inflationary by many economists. Then there's the issue of America's $36 trillion nation debt, and how cutting taxes yet again will only make matters worse there. The longer-term discussion "is where is monetary policy going to be relative to fiscal policy" in the context of large fiscal deficits, says Andrew Hollenhorst, chief US economist at Citigroup. Fed Chair Jerome Powell on Thursday made clear he's prepared to call out fiscal authorities over unsustainable borrowing, and that he's open to scaling back interest-rate cuts if inflation fails to head back to a sustained 2% pace. He also declared he wouldn't resign if he came under pressure from Trump—who is likely to be unhappy with still-high borrowing costs. The Fed will have company when it comes to considering how to respond to the policies of new administrations. The Bank of Japan earlier this year kicked off its first cycle of rate hikes since before the global financial crisis, a move that stoked the ire of some politicians. Now it faces a new wave of inflation. Trump's victory sent the dollar higher, which for Japan means a weaker yen—something that boosts price pressures. Then there's Japan's own new policy outlook.  Shigeru Ishiba, Japan's prime minister and president of the Liberal Democratic Party, speaking in Tokyo on Oct. 28 following the loss of his ruling coalition's majority in the lower house. Photographer: Kiyoshi Ota/Bloomberg After losing its majority in Japan's elections last month, the ruling Liberal Democratic Party is negotiating terms to form a coalition with a party that wants to raise the basic tax-free income allowance—even in the face of outsize deficits. In Britain, the new Labour government unveiled a big package of tax hikes to address the budget calamity left behind by Sunak and the Tories, as well as new borrowing that stoked fresh concern about inflation just weeks after the consumer price index fell back to target. UK retailers this week warned that some tax measures will themselves lead to higher shopfront prices. While the Bank of England sees the new budget from Chancellor of the Exchequer Rachel Reeves adding to inflation, Governor Andrew Bailey said Thursday there was no immediate need to change the trajectory of easing. And in Germany, the government effectively fell apart over now-fired Finance Minister Christian Lindner's refusal to increase borrowing in order to revive the country's lackluster economy. While neither of the two biggest parties is favoring a major shift away from strict German fiscal rules, the odds are the next government—following elections expected in early 2025—will be less thrifty. That assessment was clear in moves in the bond market. According to Jen of Eurizon SLJ, the mass-ouster of incumbent governments reflects a world "still recoiling" from untrammeled globalization: as rewards accumulated for owners of capital, labor interests were sidelined, he wrote in a note this week. That's why "policies in the West have turned from promoting the interests of the multinationals to protecting the rights and interests of their workers." And that in turn means more bad news for central bankers, who may have thought they could finally breathe easy. —Chris Anstey and Malcolm Scott |

No comments:

Post a Comment