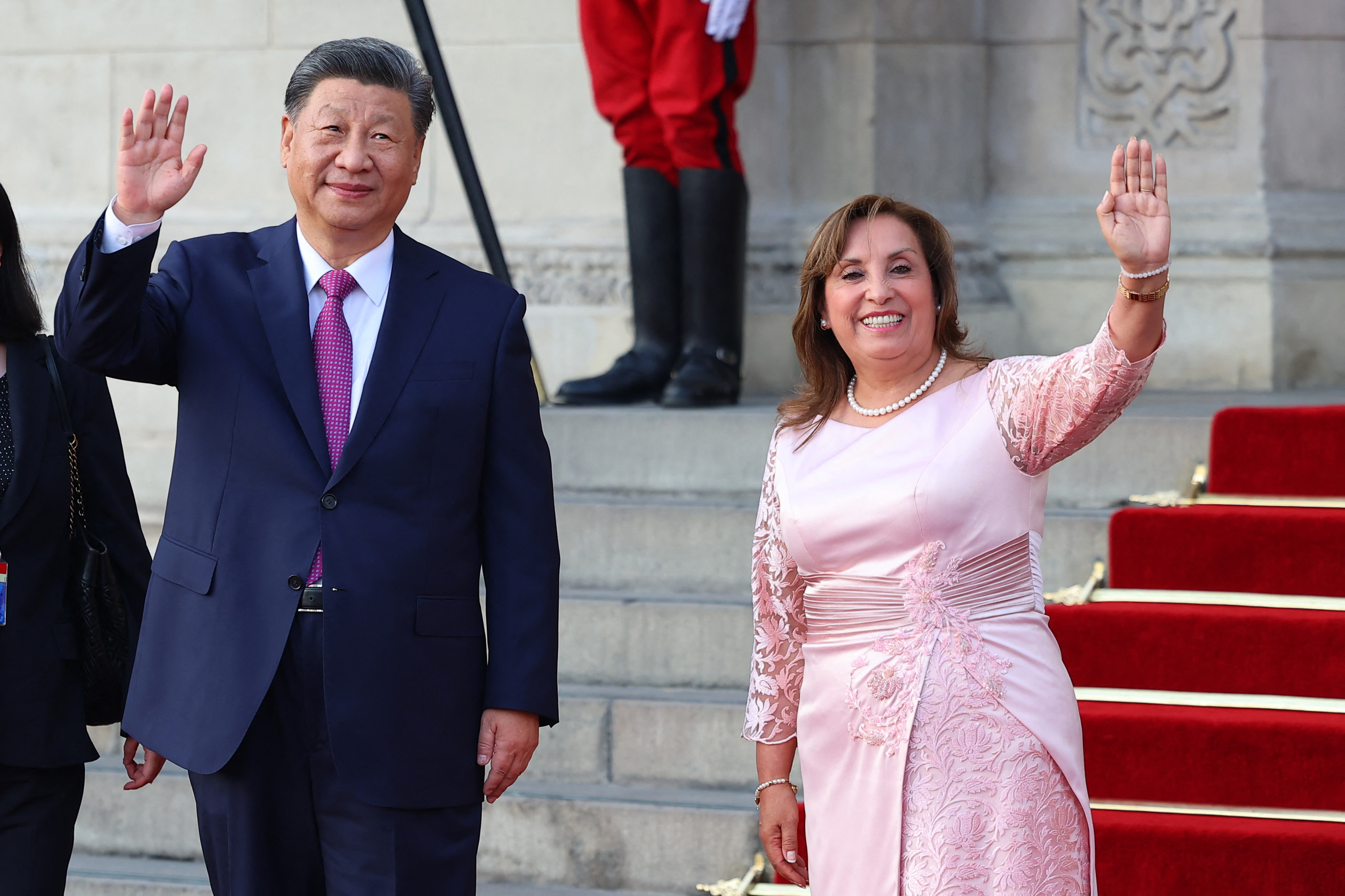

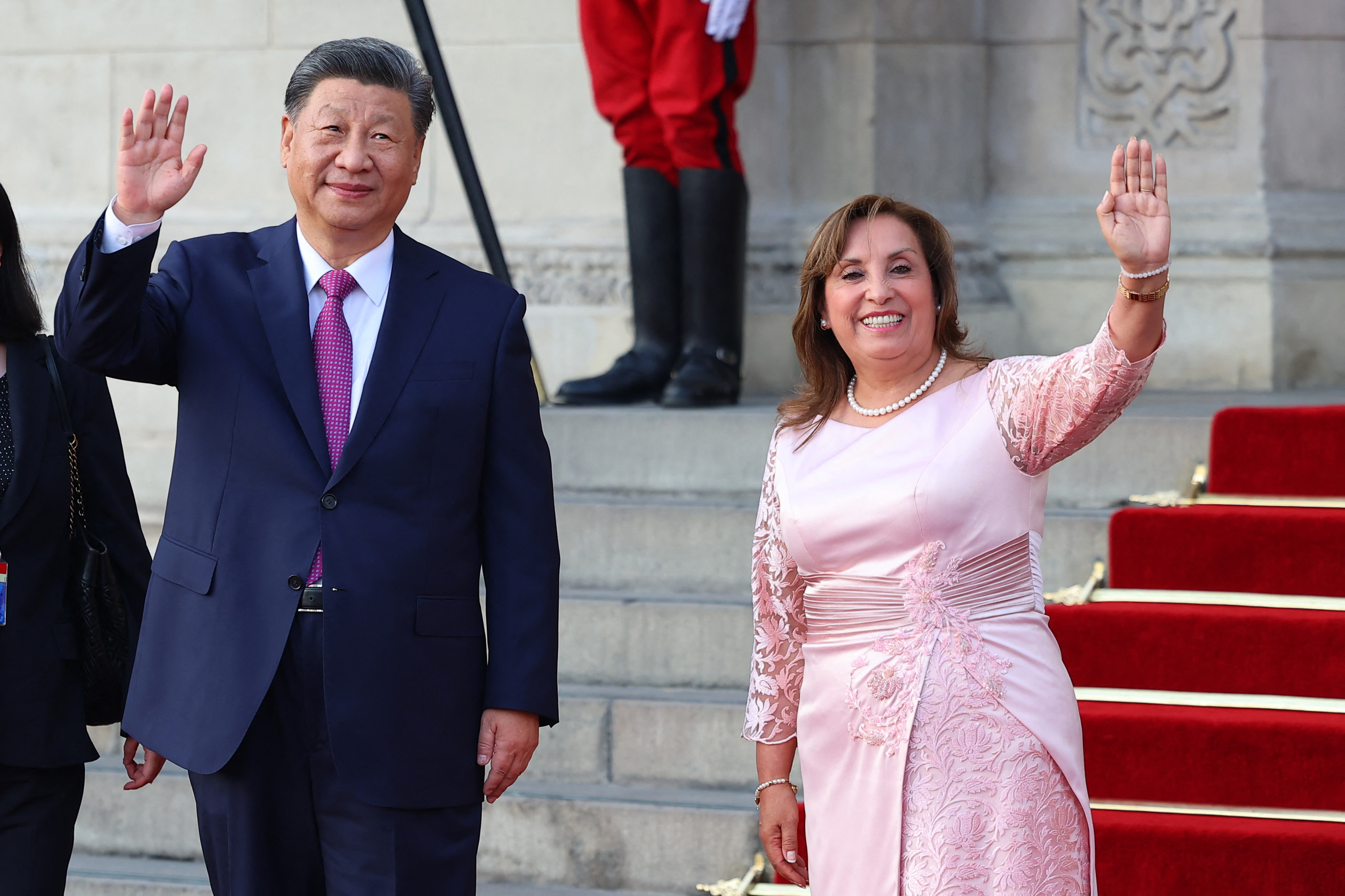

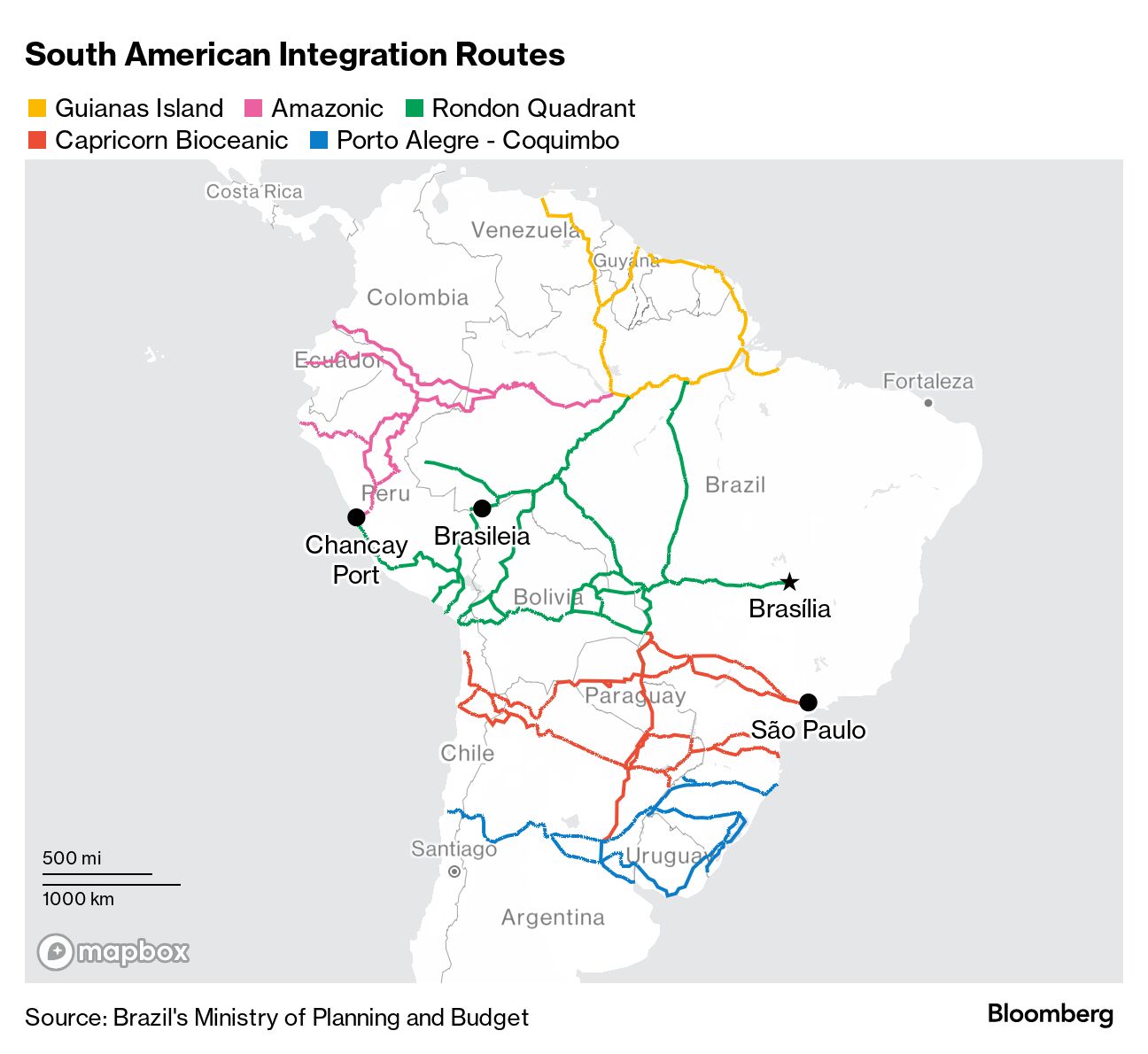

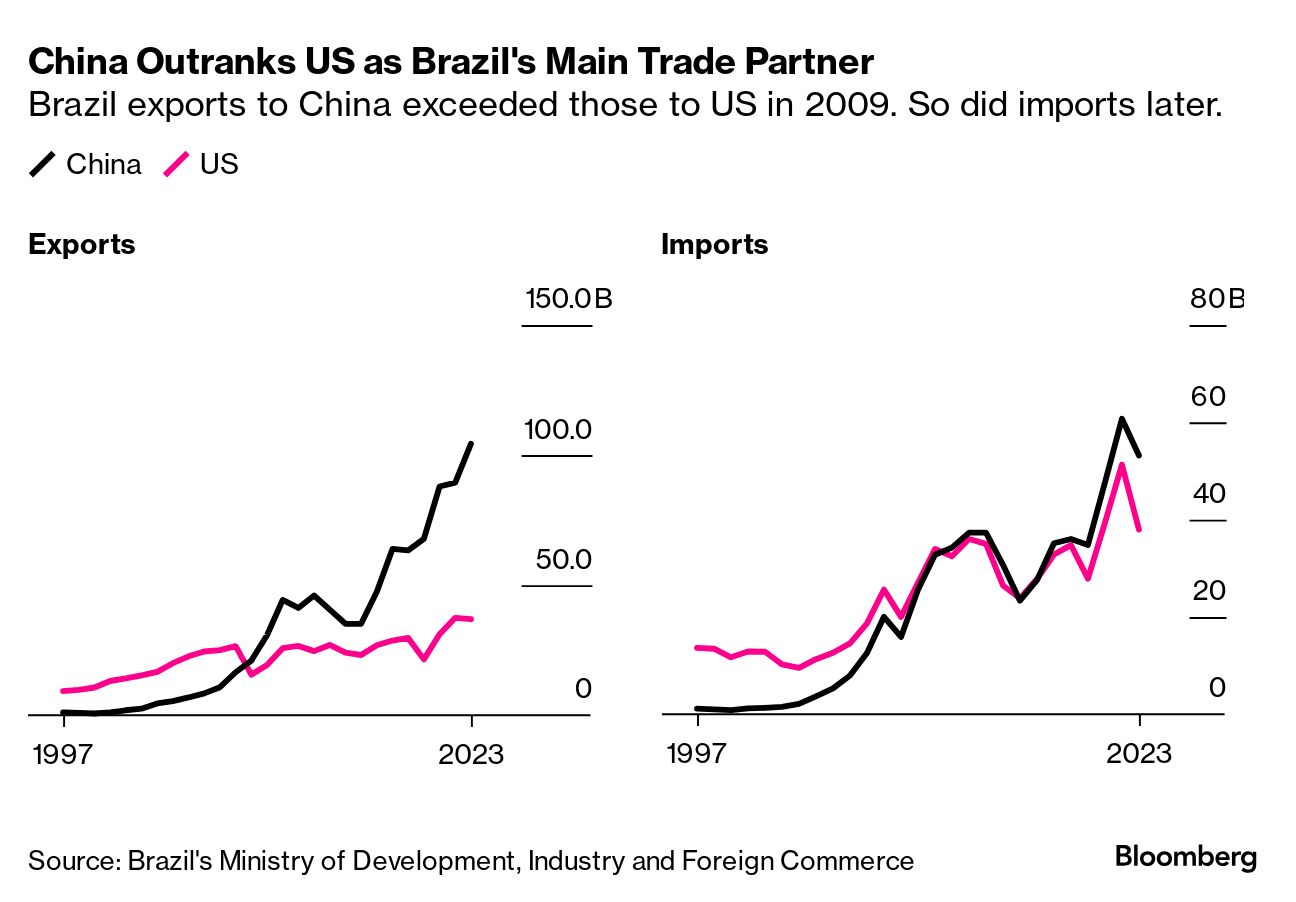

| Latin America this month will have hosted two key summits. One is the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum, and the other is the Group of 20. Both are products of the heyday of globalization in the late 1980s and 1990s. Those were the days when negotiators envisioned ever-lower trade barriers, boosting productivity and living standards for all. APEC was supposed to foster trade and common prosperity across the Pacific Rim, while the G-20 was created to manage financial risks from increased capital-market linkages. There also was another project of the era, though it never took off: the Free Trade Area of the Americas, or FTAA. Conceived at the 1994 "Miami Summit of the Americas," the FTAA (some dubbed it WAFTA to rhyme with the just-completed North American Free Trade Agreement, or NAFTA) would be the world's biggest trade grouping, stretching from Alaska to Patagonia and binding the US to fellow democracies in the region. But after the turn of the century, support for trade rapidly evaporated in Washington, and FTAA faded away. Europe, too, conceived of freer trade with South America, launching talks in 1999 with Mercosur, a potential four-nation powerhouse including Brazil and Argentina. But a quarter century on, there's still no deal. Now, as is being made clear at both the APEC and coming G-20 summit, the region is turning to another suitor. You know who.  Chinese President Xi Jinping, left, with Peruvian President Dina Boluarte in Lima on Nov. 14. Photographer: Hugo Curotto/AFP The once-travel shy Chinese President Xi Jinping this week showcased what his nation has to offer by inaugurating a $1.3 billion port in Peru, ahead of the APEC summit in the capital city of Lima. Chancay, a modern port with the kind of automation the US lacks, will establish a direct line to Shanghai, reduce shipping times and lower logistics costs. It's just one megaproject built and financed by Chinese enterprises across the continent that are reshaping transport. In Peru's giant neighbor Brazil—which will host the G-20 summit next week—a new road and rail system will ultimately cut the journey time of goods destined for China by 10-12 days. Xi is using his trips to Lima and Rio de Janeiro to portray himself as a champion of globalization in the face of US President-elect Donald Trump's gleefully protectionist approach to trade. Xi said Friday that "dividing an interdependent world is going back in history," and pledged that Beijing will unilaterally open its door wider to the rest of the world. By contrast, the Republican headed to the White House again has proposed not just steep tariff hikes on China, but a universal tariff of 10% to 20% that would hit everyone. "Trump is expected to offer international partners fewer incentives for cooperation and a more transactional approach than the Biden administration," Alicia Garcia Herrero, chief Asia Pacific economist at Natixis, wrote in a note this week. "This should bring the Global South even closer to China." Economic realities are likely to weigh heavily even on Latin American leaders that share Trump's views in other respects. Right-wing Argentine President Javier Milei, when campaigning for the post last year, vowed to curb ties with China, saying "would you trade with an assassin?" Yet the Trump fan—Milei paid his respects at Trump's Mar-a-Lago resort in Florida Thursday—has hardly followed through. Just the opposite: earlier this year, Argentina began shipping corn to China for the first time in 15 years. And there's been no (public) cancellation of the 50-year lease China has on a space station it's constructed in remote Patagonia that's stoked US security concerns. In neighboring Brazil, economic realities also are on display in the northeast state of Bahia, as Bloomberg Opinion's Juan Pablo Spinetto highlighted this week. China's BYD Co. is finishing an electric vehicle plant there that used to be a Ford Motor Co. facility. Ford shut the operation as part of its broader exit from Brazil after more than a century of manufacturing in the country. Ties with China are likely to differ across the region, says Adriana Dupita, an economist at Bloomberg Economics. "Among the major Latam countries, Brazil, Mexico, Colombia and Peru are what we call the "New Neutrals," whereas Argentina and Chile are more pro-Western. In the case of Mexico, Dupita's colleague Felipe Hernandez says that while that nation has benefitted from a major influx of Chinese investment, it's likely to come under pressure from Trump to raise barriers, such that Chinese manufacturers cannot get around US tariffs. "There is little room for negotiation for Mexico" if it wants to extend its United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) trade deal with the US and Canada when it comes up for review in 2026, Hernandez says. Hernandez also notes that not all Chinese projects in emerging and developing nations have gone swimmingly: some have collapsed in debt. Some just collapsed. Ecuador has grappled with rolling blackouts this year amid a host of problems with a Chinese-built hydroelectric plant less than 10 years old. Still, it's hard to envision Trump embracing US funding for a South American power plant. And with Europe preoccupied with the prospect of confronting a seemingly conflict-hungry Russia with less backing from Washington, China will continue to be a powerful lure as an economic partner. —Chris Anstey |

No comments:

Post a Comment