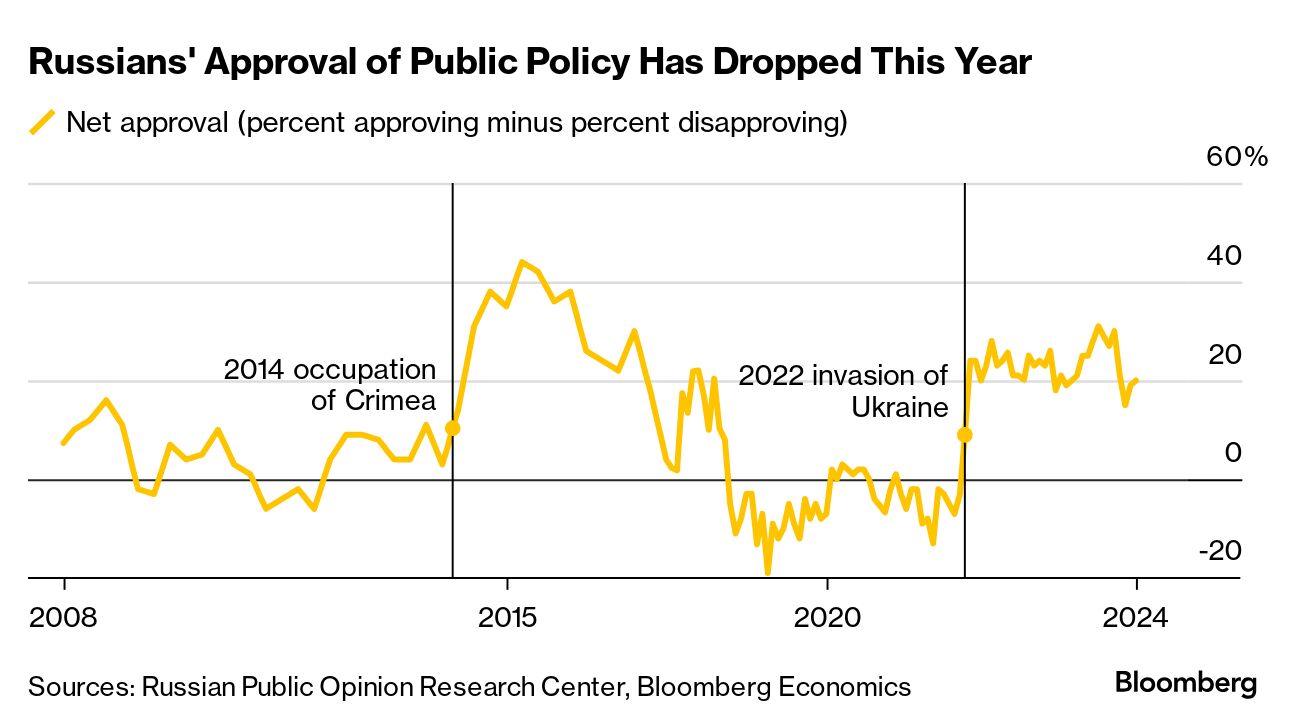

| Shut out of the dollar-based global financial system, cut off from most trade with the West and bogged down in what Vladimir Putin foolishly thought would be a blitzkrieg-like defeat of Ukraine, Russia has nonetheless seen its economy outperform in recent years. Of course, Moscow got by with a little—or a lot—of help from its friends: China, India and others were happy to import energy volumes Russia could no longer send west. Putin's regime also was able to shield the middle class from the full consequences of his bloody war of aggression through its own actions—including by propping up the ruble's exchange rate to limit inflation. But things are going to get tougher for the Kremlin leader and alleged war criminal, according to Alex Isakov, a Bloomberg economist who once worked at Russia's central bank. Moscow has drained more than half of its sovereign wealth fund in propping up the ruble—which this week nevertheless hit its weakest point since the early part of the war. And sky-high borrowing costs soon will bite Russian consumers as the central bank tries to keep a lid on inflation, bringing home a financial cost to a war that's killed tens of thousands of people in their name. Where Putin's war on Ukraine goes in 2025 is perhaps impossible to predict, particularly given the uncertainty about how a Moscow-friendly Donald Trump will approach the conflict when he takes office. But one thing seems certain: next year will be a "year of consumer retrenchment" for Russia, as Isakov puts it, because Putin can no longer guarantee both guns and butter. (For Isakov's full note on the Bloomberg terminal, click here.)  Vladimir Putin Photographer: Sergei Guneyev/AFP/Getty Images Bloomberg Economics projects a slowdown in Russian economic growth to just 1% next year from an estimated 3.1% in 2024. And it isn't alone. The International Monetary Fund also sees a sharp drop, to 1.3% next year, driven by weaker private-sector consumption and investment. Even if the war ended, "a sharp slowdown seems likely, given the absence of structural growth drivers," Melis Metiner, an economist at HSBC, wrote in a recent note. "Demographic trends are negative, productivity gains appear unlikely in the near-term and physical capital accumulation is likely to be constrained by access to financing." A key challenge is that, "with fiscal buffers approaching depletion," Putin cannot avoid a transformation into a full-blown "war economy," Isakov says. Before its full-scale Ukraine invasion in February 2022, Russia had accumulated as much as $140 billion in liquid assets—that is, those that can easily be sold—in its National Wealth Fund (NWF). That total slid to around $55 billion as of last month. Take out gold, and it's just $31 billion, or almost the same as when the Russian piggy bank was established in 2008. Isakov says Moscow has been selling off Chinese yuan to prop up the ruble's exchange rate. China of course is Russia's senior partner in most things, including its dominant source for consumer imports now that trade with the West has been decimated. With diminished capacity to cushion the ruble, a weaker exchange rate will mean more inflation for Russian consumers (many of whom favor continuing the bloodshed in Ukraine, according to a recent poll). The central bank will also be less able to lower interest rates. The Bank of Russia's benchmark now stands at 21%, and is likely to stay at double-digits for years to come, Isakov says. If the Kremlin opts to completely drain the NWF, its budget will become particularly vulnerable to even short-term declines in the prices of energy, Russia's main export—a similar position in which the Soviet Union found itself in the 1980s. And we all know (as one would expect Putin does) how that turned out. What's more likely is a redirection of focus away from consumers. Moscow will "aim to accelerate a transfer of scarce labor and capital from sectors deemed non-essential, such as services, residential construction and finance, to those that are considered critical to giving Putin a military advantage," Isakov says. A true war economy, in other words. This reality is starting to sink in: even Russia's official public policy approval index shows a decline this year. It's now around the lowest reading since the start of the war. —Chris Anstey |

No comments:

Post a Comment