| Poultry is on our minds this week. Businessweek's food columnist, Deena Shanker, writes about what the nominee for secretary of health and human services can do to regulate the food industry, among other changes aimed at improving Americans' health. And Odd Lots is making a whole mini-series about the mighty chicken. Plus: the difficult math ahead for Donald Trump to fulfill his promises, and what tech billionaires get wrong about the "Gell-Mann Amnesia effect." If this email was forwarded to you, click here to sign up. You can learn a lot from the economics of poultry. First, let's look at a chicken fight from a few years back. As Bloomberg's Deena Shanker writes in today's Extra Salt column, President Barack Obama took a big swing at helping chicken farmers who were battling the big companies that controlled the industry. Obama wanted to make rules so it would be easier for the farmers to sue and to change the way they were paid. But then Donald Trump took over the White House: Obama left office before they were finalized, but farmers thought Trump would take their side. "Big Meat doesn't want it to happen," a former poultry farmer who wanted the rules but voted for Trump told me in January that year. "People down here are expecting Trump to pull it off," she said. He didn't. That October his US Department of Agriculture took industry's side and killed the Obama rules, putting another nail in the coffin of his presidency's half-hearted attempts to capitalize on a growing movement of Americans who wanted to change the way the country's food is produced.

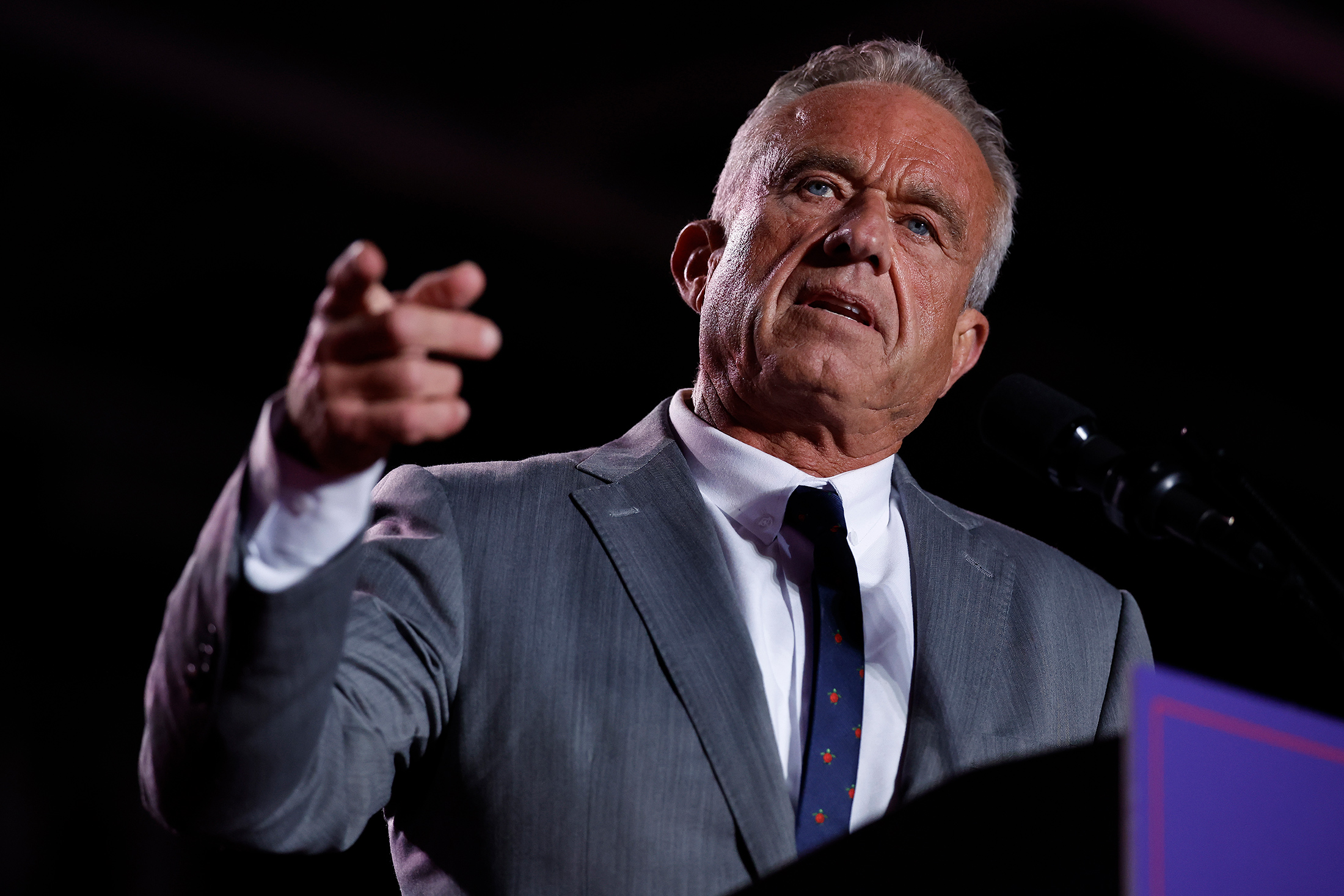

Trump has pledged that Robert F. Kennedy Jr. will end the control of the "industrial food complex." Photographer: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images This might be a warning to those who hope that Trump's pick to run the Department of Health and Human Services, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., will fulfill the promise of his slogan to "Make America Healthy Again." Shanker writes: If approved by the Senate, Kennedy would oversee agencies including the Food and Drug Administration to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. While his most dangerous views, such as opposition to vaccines and fluoridated water, have gotten the most attention, his plans for reforming the food system, according to what he's said during the campaign, are as ambitious as Trump describes them. He wants to get ultraprocessed foods out of schools, artificial dyes out of cereals and pesticides out of agriculture. He's advocating for the kind of changes that usually come from the left. That's less surprising when you realize Kennedy was once not just a Democrat but also an environmental lawyer who sued Monsanto Co.

You'll have to read the whole column to see whether these promises are even remotely possible. Second, let's go over to the podcast Odd Lots, where Joe Weisenthal and Tracy Alloway are taking a different look at why chickens matter—as a "perfect prism" to examine macroeconomic trends. Alloway writes: We know, for instance, that food prices have been a huge part of the inflation story, with the cost of eggs even becoming a political talking point in the recent election. So how much of that price rise was about supply versus demand? How do companies decide to price stuff like an egg or a chicken wing anyway? And what can it all tell us about how inflation actually works? There's also a big labor story to tell here. Chicken production has a kind of idiosyncratic labor market, with big poultry producers like Tyson and Perdue outsourcing a lot of chicken growing to independent contractors. But that model has become more and more common in agriculture—and beyond. Today, we're used to talking about companies like Uber pioneering the whole "big intermediary with a network of independent contractors" thing, but chicken was there before!

To tell this story, Odd Lots has produced a special three-part series called Beak Capitalism. Listen to the first episode here. Between the cost of eggs (a perennial issue, as readers of this newsletter know) and the MAHA movement, expect to see chickens in the news often in the next few months. Except for that one day when another bird gets its wings—Thanksgiving, of course, is almost upon us. |

No comments:

Post a Comment